Summary:

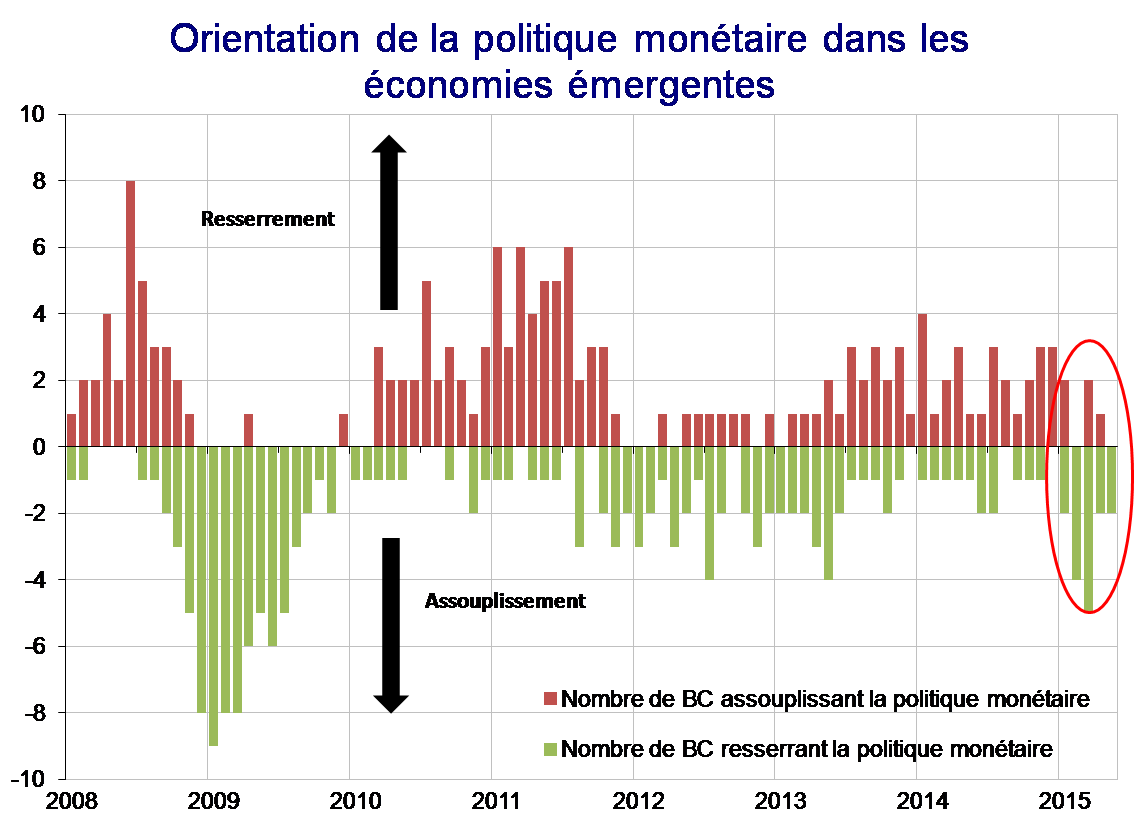

– Since the beginning of the year, monetary policy has been easing in the major emerging economies.

– This trend comes against a backdrop of disappointing economic performance and falling inflation.

– Divergent monetary policies in the United States, Europe, and Japan also appear to have played a role.

– Asia is the region where the trend toward monetary policy easing is most pronounced.

1 – A cycle of easing since the beginning of 2015…

From the second quarter of 2013 and throughout 2014, central banks in emerging economies tightened their monetary policy, notably by raising key interest rates, for fear of capital flight amid the Fed’s gradual exit from quantitative easing. Of the fifteen countries considered[1], only four (Thailand, China, Poland, and Saudi Arabia) did not raise their key interest rates in 2013 or 2014, with all other countries raising theirs, sometimes dramatically (as in Turkey in January 2014 or Russia in December 2014 under special circumstances).

The start of 2015 seems to mark a fairly clear break in the monetary policy of emerging economies. Most central banks are pausing, and in some cases are already easing their monetary policy. With the exception of Brazil and Argentina, none of the major emerging market central banks raised their key interest rates in 2015; on the contrary, eight of them (Indonesia, Thailand, India, China, Argentina, Poland, Russia, and Turkey) began to cut them.

Sources: Macrobond, BSI Economics

This easing of monetary policy can be explained by a number of factors, foremost among which are (i) the continuing slowdown in emerging economies and persistently negative output gaps, which are prompting the authorities to support economic activity (ii) lower inflation in a context of low oil prices, which gives central banks some room for maneuver, and probably (iii) reduced fears in some countries about capital flight linked to monetary policy developments in advanced economies.

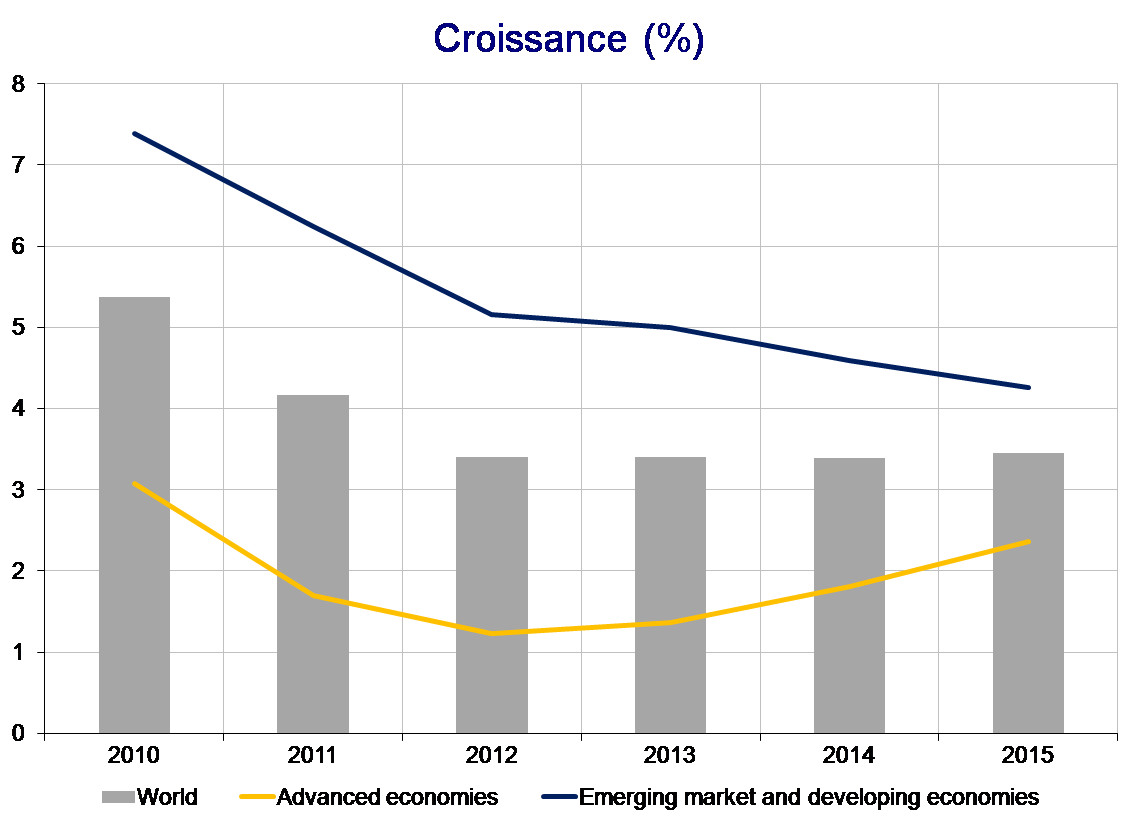

2 – … against a backdrop of slowing emerging economies…

The IMF’s latest forecasts (World Economic Outlook (WEO) April 2015) saw a further downward revision of growth forecasts in emerging economies, from 5% in the October 2014 WEO to 4.3% in the latest WEO. If this figure is confirmed, 2015 would be the fifth consecutive year of economic slowdown, which contrasts sharply with the recovery observed in advanced economies since 2013. In addition, growth figures for Q4 2014 and Q1 2015 were disappointing in several major emerging countries, notably China (7% in Q1 2015), Indonesia (4.7%), South Africa (1.3%), Colombia (3.5%), and Turkey (2.6%).

Sources: Macrobond, BSI Economics

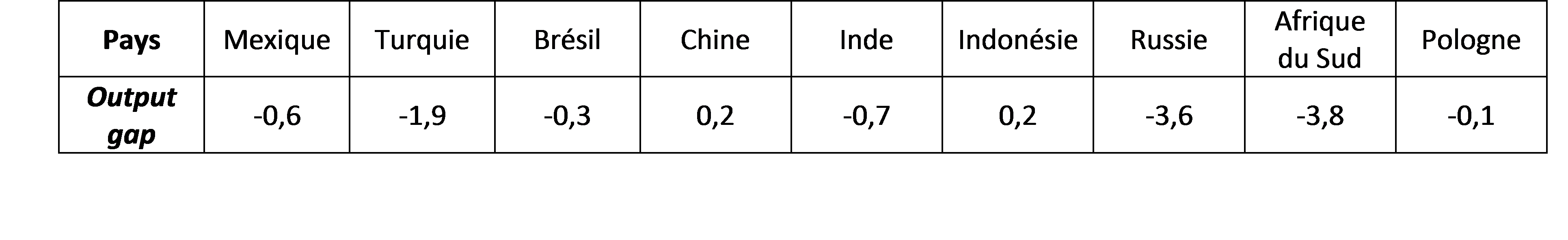

More important than the level of growth itself, it appears that most emerging economies are experiencing a negative output gap [2](despite the decline in their potential growth since the financial crisis). The IMF estimatesthe output gap in emerging economies at -0.7% of potential GDP in 2014.

Sources: IMF, OECD, BSI Economics

3 – … and falling inflation in some countries

Monetary easing in emerging economies is also taking place against a backdrop of slowing prices. Over the past few years, average inflation has trended downward (from 7.3% in 2011 to 5.1% in 2014), and this trend has accelerated more recently in most countries, thanks to lower oil prices. This decline since the summer of 2014 has had a strong impact on inflation in emerging economies, particularly those in which oil products account for a significant portion of the consumer price index. However, beyond this overall trend, there are specific dynamics at play in different regions and countries.

Sources: Macrobond, BSI Economics

In most countries, inflation has fallen thanks to lower energy prices

Asia appears to be the region benefiting most from lower commodity prices. India, China, and ASEAN countries have seen inflation fall significantly over the past twelve months. A recent study by the IMFon Asia estimates that the common factor explaining the variation in inflation in emerging Asia appears to be relatively synchronized with changes in commodity prices. In India, for example, the Central Bank estimates that a 10% drop in oil prices reduces inflation by 20-25 basis points.

In South Africa, inflation has fallen sharply since its peak in August 2014 (6.4%), dropping below 4% at the beginning of the year, mainly due to lower fuel prices. In Turkey, inflation fell sharply in January and December, before picking up slightly in recent months.

Some countries are experiencing specific situations that explain the rise in inflation

In Brazil, the fall in the exchange rate since Q3 2014 has generated imported inflation, which is pushing prices up and forcing the Central Bank to tighten monetary policy drastically. Begun in mid-2013 during the financial tensions that affected all emerging economies, the rise in interest rates has been virtually uninterrupted since then.

In Russia, the fall in oil prices (on which the economy is totally dependent in terms of budget revenues and exports) has compounded the economic and financial sanctions linked to the Ukrainian crisis, all against a backdrop of structural weaknesses in the economy. The fall of the ruble (currency crisis in mid-December and depreciation of nearly 40% in Q4 2015) quickly spread to prices, which jumped in early 2015 (inflation of 16.9% in March).

Some countries took advantage of the opportunity offered by lower oil prices to undertake subsidy reforms (Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, etc.). This was particularly the case in Indonesia, which explains the rise in inflation in November and December 2014, before it fell back at the beginning of the year.

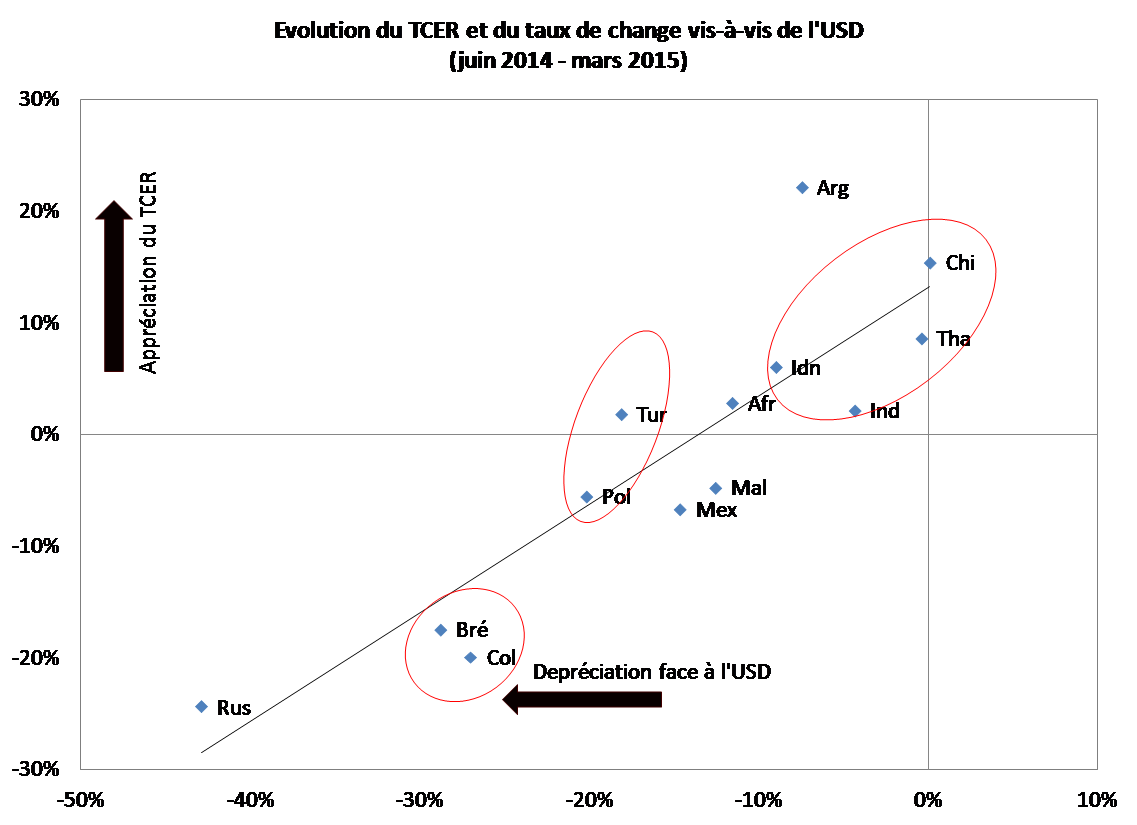

4 – Asynchronous monetary policies in advanced economies

In the United States and the United Kingdom, the recovery in growth and the decline in unemployment have led to the gradual phasing out of asset purchase programs, and interest rates could rise by the end of the year. Conversely, the European Central Bank has just embarked on a massive asset purchase program, while the Bank of Japan is continuing its expansionary policy as part of « Abenomics. » The divergent monetary policies in advanced economies and their impact on exchange rates (rebound of the dollar and depreciation of the euro and yen) have different effects depending on the region and country (and thus on the policies of central banks), based on their economic and financial proximity to the United States, Europe, and Japan.

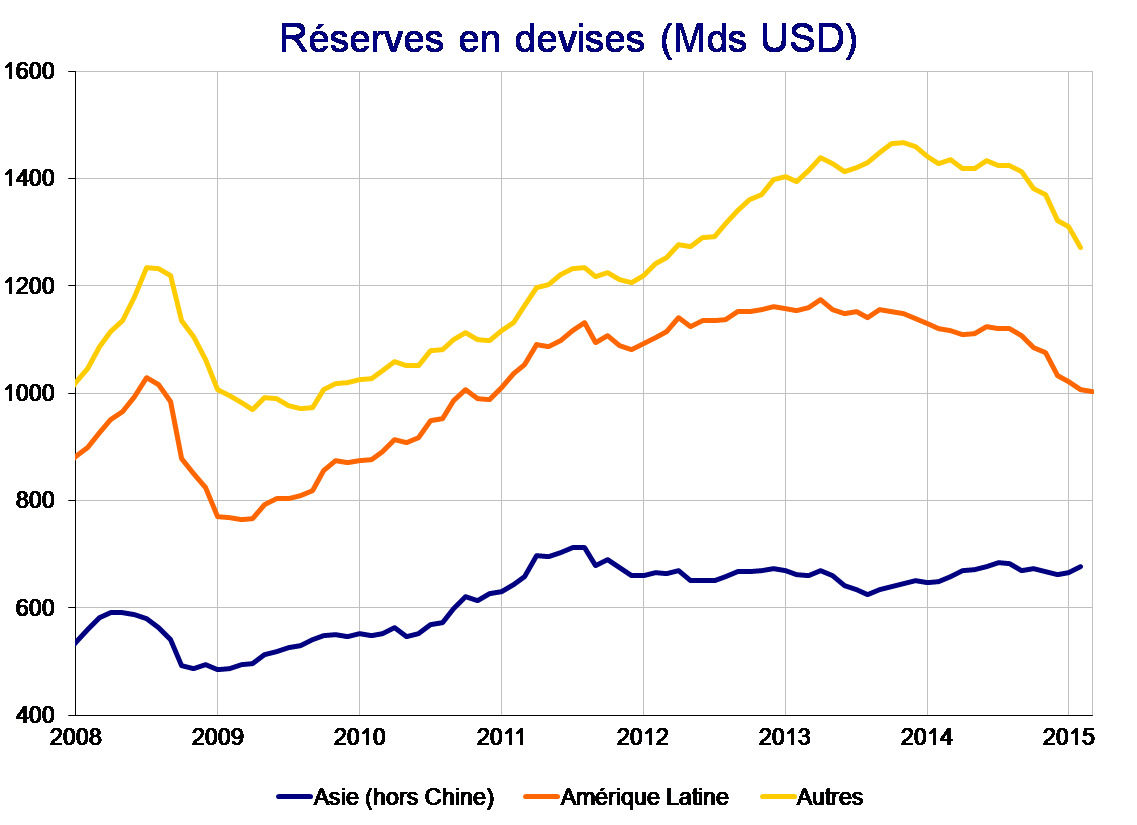

Asian economies are holding up well against the rise of the dollar, and the fall of the yen is pushing up their real effective exchange rates, which undoubtedly explains why Asian central banks have so far been the most inclined to ease their monetary policy (Indonesia, Thailand, India). This hypothesis seems to be confirmed by the trend in foreign exchange reserves, which are rising in Asia (albeit very slightly), while falling quite sharply in other emerging regions.

The situation in Poland and Turkey is ambiguous. Despite falling sharply against the USD, their currencies have remained stable in real effective terms. More dependent on euro movements (both commercially and in terms of external debt), the Polish and Turkish central banks are thus more inclined to follow European monetary policy, as shown by the recent rate cuts in both countries.

Sources: Macrobond, BSI Economics

Conclusion

In conclusion, it appears that a move towards monetary policy easing in emerging economies is indeed underway in most emerging economies. The task now is to observe the extent of this reversal in the coming months/quarters. This shift could quickly bring back old demons that are well known to central bankers in emerging economies.

Internally, monetary policy easing and credit recovery could increase financial stability risks in some countries, particularly through increased household or corporate debt. Externally, the revival of credit and economic activity could further worsen the current account deficit and once again expose the countries concerned to turbulence when monetary policy tightening in advanced economies actually takes place, which some anticipate will happen at the end of next year and are already calling the » Triple Tantrum. »

Notes:

[1] The sample of emerging economies considered in this article includes fifteen of the largest emerging economies in terms of GDP (2014, in current USD): China, India, Russia, Brazil, South Africa, Indonesia, Thailand, Colombia, Mexico, Turkey, Poland, Malaysia, Argentina, Nigeria, and Saudi Arabia.

[2]The output gap is defined as the difference between demand-driven output and potential output determined by supply (based on the factors of production, labor and capital, as well as total factor productivity). A negative output gap means that output is below its potential.