DISCLAIMER: The opinions expressed by the author are her own and do not necessarily reflect those of the institution that employs her.

Abstract:

- Rising inflation rates in the eurozone have led the European Central Bank (ECB) to tighten its monetary policy, raising fears of increased pressure on the sovereign bonds of the region’s most vulnerable countries.

- The ECB has therefore announced the creation of a new Transmission Protection Instrument, aimed at preventing excessive divergences between European sovereign bond yields.

- However, the lack of information about the circumstances in which this tool could be implemented raises doubts about its actual effectiveness.

The ECB has announced the introduction of a new tool to address the widening spreads between European interest rates in a context of monetary tightening. This Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI )[i] is designed to combat the risk of fragmentation in the eurozone by allowing the purchase of assets from the most vulnerable countries.

Nevertheless, many uncertainties remain, particularly regarding its conditions of application.

What is the Transmission Protection Instrument and what circumstances led the ECB to introduce it?

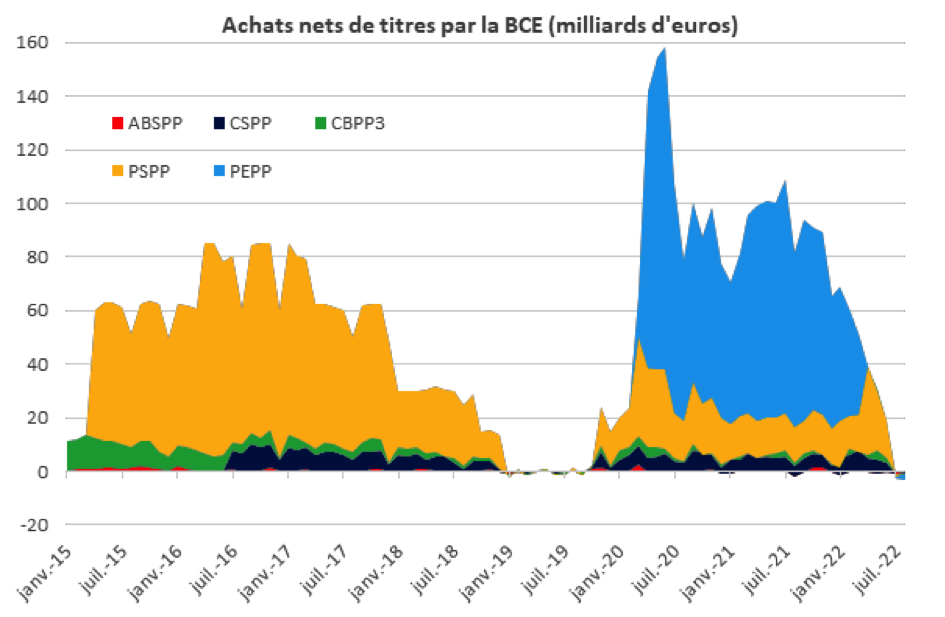

After several years of fiscal effort, the pandemic has led to an increase in debt ratios within the eurozone, particularly in countries that were already heavily indebted, such as Spain (118% of GDP according to Eurostat), Portugal (127%), and Italy (151%). The rise in spreads, i.e., the difference between the interest rates on a country’s sovereign debt and those of a country considered « risk-free » (Germany in the case of the euro area), which gives an idea of the risk premium for that country, was limited by the ECB’s intervention through its quantitative easing program: the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program(PEPP).

However, net purchases of securities under the PEPP ended in March 2022, which has since contributed to the widening of spreads, amplified by the emergence of new risks threatening the global economy, notably the energy crisis linked to the war in Ukraine. With the end of the Asset Purchase Program(APP) in July 2022, the ECB further reduced liquidity in European markets. This program, which dates back to 2015 and was relaunched at the start of the pandemic, was intended to ease monetary conditions in the eurozone and had particularly benefited vulnerable countries, whose debt could be purchased by the ECB on the secondary market.

Source: Haver, ECB. ABSPP: Asset-Backed Securities Purchase Program. CSPP: Corporate Sector Purchase Program. CBPP3: Covered Bond Purchase Program. PSPP: Public Sector Purchase Program. PEPP: Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program.

Faced with the need to tighten its monetary policy due to rising inflation, the ECB accompanied its first rate hike in ten years in July 2022 with the introduction of the TPI, against a backdrop of fears about the stability of the monetary union.

The stated objective of the TPI is to ensure the effective transmission of monetary policy in all euro area countries. In practice, it allows for the purchase of securities on the secondary market, similar to the previous quantitative easing programs implemented by the ECB during previous crises. Purchases target securities issued specifically by countries suffering from a deterioration in their financing conditions that is not justified by their economic fundamentals. This means that the use of the TPI would become possible when borrowing costs rise disproportionately to the deterioration in the public finance outlook, particularly as a result of speculation. The eligibility conditions were announced at the same time as the instrument and require countries to (i) comply with the European Union’s fiscal framework[1], (ii) not suffer from severe macroeconomic imbalances[2], have a stable fiscal trajectory, and (iv) pursue sound and sustainable macroeconomic policies.

What are the expected benefits of this instrument?

According to the ECB, this instrument would enable its monetary policy to be effectively transmitted to all eurozone countries, despite structural and cyclical differences. Implicitly, by seeking to limit the rise in spreads, the ECB aims to avoid a disproportionate impact of its monetary tightening on the growth prospects of the most indebted countries. The TPI thus allows the ECB to maintain the protective aspect of previous quantitative easing programs for the most vulnerable economies, while raising its key interest rates to combat inflation.

This instrument was preferred to other alternatives, notably a smaller increase in the ECB’s key interest rates. While this option could also have limited the risk of fragmentation, it has the major disadvantage of not sending a strong signal of the ECB’s willingness to combat rising inflation in Europe. With inflation reaching +9% in the summer of 2022, it was necessary for the ECB to anchor inflation expectations by raising its rates significantly, confirming its commitment to pursuing its price stability mandate.

Furthermore, previous asset purchase programs appeared to have exhausted their effects. Indeed, despite an initial effective reduction in spreads of up to 60%, this seemed to plateau after a certain period of time. As the amounts invested by the ECB in each jurisdiction are limited, the effects of the programs tend to diminish as they approach their maximum. The end of QE programs is not likely to cause an immediate rise in spreads in benign market conditions, but the return of greater volatility in the markets has prompted the ECB to equip itself with the TPI in order to preserve the effects of past programs.

The TPI also responds to the risks of disruptions in the repo market in a context of inflation control and monetary tightening. Indeed, as European sovereign bonds are used as collateral, the creation of liquidity allowed in the repo market is reduced when their rates rise. The creation of private credit by European financial institutions, which are major holders of sovereign bonds, becomes limited in these circumstances, as observed during the eurozone debt crisis. The TPI could thus counteract this possibility linked to rising sovereign rates.

By launching a securities purchase program that should favor the most indebted countries, the ECB is also confirming its confidence in these economies to the financial markets.

Are there any risks associated with the introduction of this tool? What will the ECB and the markets be watching out for in the coming months?

There is still considerable uncertainty surrounding this new instrument, particularly with regard to the decision-making process for its implementation. Although the European monetary authorities have specified that the tool should only be used in the event of disorderly and unjustified rate divergence, this definition is not accompanied by clearly stated conditions for its application. It implies that the ECB may allow spreads to widen without activating the TPI if this increase is « orderly, » and therefore that the activation threshold may be high. Nevertheless, the accumulation of risks to the growth outlook could prompt some governors to want to act sooner than anticipated. The ECB will then have to deal with divergent opinions on the appropriate time to activate the tool.

While the eligibility conditions are clearer than the conditions for application, there remains a risk that monetary authorities may be led to circumvent them if the survival of the single currency were to be threatened. If seen as a safety net, this instrument could reduce the incentive for governments to take « serious » decisions on fiscal policy.

Finally, the legality of the EPP, like the ECB’s previous quantitative easing programs, could be challenged in the European Court of Justice or the German Constitutional Court. The ECB is authorized to purchase sovereign bonds, but these purchases are limited by European treaties so that they do not lead to direct monetary financing. They will also be more difficult to justify in a context of rising inflation. If the ECB wants to avoid a legal challenge, it should « sterilize these purchases, » i.e., ensure that the size of its balance sheet does not increase as a result of using this instrument. However, no details were given when the TPI was announced on how to control the impact on its balance sheet.

Several different events could lead the ECB to use the TPI, for example:

· If the government of a eurozone country sought to review the conditions for access to the European Commission’s recovery plan by reneging on its structural reform commitments;

· If a sustained rise in inflation required a sharp increase in key interest rates and significantly worsened the growth prospects of the most indebted countries;

· Or in the event of excessive speculation, if investors sought to take advantage of differences between sovereign rates.

At the same time, financial markets will be watching closely for the monetary authorities’ reactions to sudden and significant changes in the economic outlook for the eurozone and political risk.

Many gray areas remain

In theory, therefore, the TPI seems capable of easing potential tensions on sovereign bond markets in a context of monetary tightening that penalizes the most indebted countries.

In practice, the conditions under which this instrument could be implemented remain unclear, suggesting that the ECB hopes that its existence alone will be enough to avoid the market conditions that would require its implementation. Nevertheless, if inflation rates continue to rise in the eurozone and the ECB is forced to continue raising its key rates, the conflict between the objective of price stability and the implicit objective of maintaining spreads is likely to become increasingly untenable.

[1] Compliance with the EU fiscal framework means not being subject to an excessive deficit procedure and not having failed to take the measures recommended by the European Council.

[2] The absence of severe macroeconomic imbalances means not being subject to an excessive imbalance procedure. Only Romania has been affected since June 2022.

[3] Repo market (Sales and Repurchase Agreement): market for borrowing short-term liquidity (from one day to one year) in exchange for securities