The real estate crisis is affecting the balance of local government (LG) public accounts. In 2022-2023, almost all LGs recorded a sharp drop in real estate-related revenues, particularly from the sale of land use rights (nearly 40% of total revenues, on average).

The impact of the real estate crisis on the public balance varies greatly from one LG to another: four provinces are considered to be at high risk of vulnerability and eight at medium to high risk (including Jiangsu and Shandong).

Since 2020, local governments have been increasingly resorting to bond issues to meet their growing financing needs, a phenomenon that intensified in 2023. The existence of a refinancing risk in 2024 in several local governments could well further constrain fiscal leeway and result in less support for economic activity in some cases.

The opaque links between LGs and Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) are a source of fragility that is difficult to quantify. Based on the available information, LGFVs are facing significant debt repayments in 2024, which will be a test year for determining whether the LGs’ implicit guarantee to LGFVs actually exists.

If local governments intervene to refinance LGFVs, the impact on their public accounts would be far from negligible and would not be neutral, but rather significant. However, the involvement of other players (mainly banks) in finding a solution to a potential LGFV crisis could be envisaged, which would mitigate the impact on local governments.

China has all the characteristics of a giant with feet of clay. The real estate crisis, which has been affecting the country for several years now, is symptomatic of the shortcomings of an economic model that is running out of steam after reaching record levels of debt. But does this compromise its short-term growth prospects? While doubts remain,the assessment provided in an initial note from BSI Economicsshowed that the vulnerabilities of the Chinese economy are unevenly distributed across the country and that the risks are concentrated in provinces with relatively moderate economic weight.

This second note will take a closer look at the channels of vulnerability for provinces and local governments. It will identify the sources of risk and analyze the ramifications for the real estate sector and other players, particularly the famous LGFVs (Local Government Financing Vehicles).

The real estate crisis: the trigger for the fragility of local government public accounts

Since 2021, China has been facing a series of headwinds in the real estate market, andthis crisis seems to be continuing: a steady decline in prices, sales, investment, housing starts, etc. The real estate crisis has also revealed weaknesses among local governments (LG), which are in a state of turmoil (an appendix is available at the end of the article to better understand the links between LG and the real estate sector).

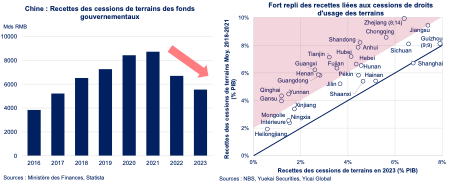

The decline in real estate prices and housing starts has a direct impact on the solvency of LGs, given thatnearly 40% of their revenues dependon the real estate sector. These revenues consist of several taxes (mainly land use tax, VAT on real estate sales, property taxes) and land use rights transfers (CDUT), which account for the bulk of these revenues[1]. CDUT revenues have collapsed since 2022 and declined further in 2023 (see chart on the left below).

Referring to the graph above on the right, all points above the bisector correspond to GLs where the CDUT revenue-to-GDP ratio deteriorated in 2023 compared to the 2018-2021 average. In the red zone, the deterioration was even more pronounced, with some very significant declines: more than 3 pts of GDP (Anhui, Guangdong, Guangxi, Henan, Hubei, Qinghai, Shandong, Tianjin) and nearly 6 pts of GDP (Zhejiang).

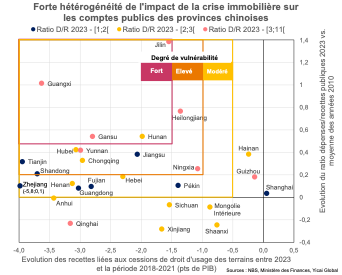

Beyond the scale of the decline in CDUT revenues, it is important to identify the provinces where the fall in real estate-related revenues has led to a deterioration in public accounts, exposing local governments to varying degrees of vulnerability. The graph below summarizes these factors by offering a three-dimensional analysis[2]: the extent of the decline in CDUT revenues (x-axis), the level of the expenditure-to-revenue ratio (E/R ratio) of local governments in 2023 (color of bubbles), and the change in this E/R ratio in 2023 compared to its average level during the 2010s (y-axis):

The main lessons to be learned from this graph:

- The red rectangle in the upper left corner represents the area where local governments are experiencing both a sharp drop in CDUT revenues and a marked increase in their public deficit (D/R ratio increasing significantly[3]), i.e., a high level of vulnerability, with four provinces having a relatively large public deficit in 2023 (red bubbles: Guangxi, Jilin, Gansu / yellow bubble: Hunan).

- The inverted L-shaped area outlined in orange corresponds to a zone where the degree of vulnerability remains high, but where the transmission of real estate risk to public finances is less pronounced than in the red zone. The profile of the provinces within this zone is more heterogeneous, with some provinces where local governments have high D/R ratios (Heilongjiang, Ningxia, Yunnan) and others where they are relatively low (Jiangsu, Shandong, Tianjin).

- The inverted L-shaped area with yellow outlines indicates a moderate level of exposure of public finances to real estate market shocks.

- In the other unidentified areas of the graph, the transmission of the real estate crisis to public finances appears to be limited or even insignificant. These include provinces where the public balance tended to improve in 2023 compared to the reference period (Inner Mongolia, Qinghai, Shaanxi, Sichuan, Xinjiang) or Shanghai, with increasing CDUT revenues (an exception in China).

Several measures have been introduced by the authorities totry to resolve the real estate crisis. At this stage, the results seem inconclusive for local governments,with revenues still sluggish inearly 2024. If the real estate crisis continues, the most vulnerable local governments would see their public revenues remain under pressure, posing a threat to their solvency. Even if the real estate market recovers, local governments would not be « out of the woods » given the other risks to the sustainability of their debt.

(In)ability to raise debt and refinancing risk: 2024, a year of high tension

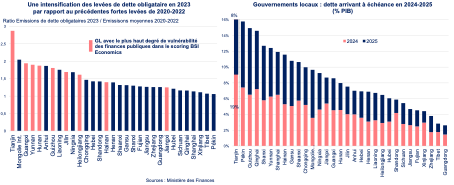

As mentioned inthe first note published on BSI Economics,12 regions(including Chongqing, Guizhou, Jilin, Liaoning, Tianjin, and Yunnan) are subject to tighter debt controls, which could weigh on their ability to support local economic activity in 2024.

It is interesting to note that among the provinces and local governments affected by these restrictive measures, several issued a larger volume of debt on the bond market in 2023 than during the period 2020-2022, when fundraising had already increased significantly. The increase in debt issuance in 2023 is on average greater in the LGs identified as having the highest degree of vulnerability in their public finances (see red bars in the graph on the left below).

More detailed data reveal that these issuances mainly took place in the second half of 2023, when the authorities sought to step up their efforts to support economic activity and when authorizations to issue in 2023 in advance of the 2024 issuance quotas were granted. There are several ways to analyze these results:

- Optimistic scenario: Lower bond issuance capacity in 2024 does not necessarily weigh on activity. The most fragile local authorities took advantage of more favorable conditions (lower interest rates) in 2023 to increase their debt issuance in advance, enabling them to secure the funds needed to carry out their investments and thus hope to achieve their growth targets in 2024.

- Pessimistic scenario: The least robust local authorities have even less room for maneuver, as their economic fundamentals do not allow them to issue large volumes of new debt given that they began their 2024 quotas in 2023. This situation could prove worrying in the event of a sluggish economy requiring additional fiscal stimulus from local and regional authorities. In such a scenario, growth targets would become difficult to achieve and would likely require increased intervention by central authorities in the form of transfers to the local and regional authorities concerned.

- Inevitable scenario: The main risk concerns refinancing in 2024. Several LGs will have to repay significant amounts of their debt in 2024 (see chart above right), with Tianjin in the spotlight, but also Beijing, Shanghai, Guizhou, Yunnan, and Qinghai. If these local governments are limited in their ability to issue new debt, they would temporarily encounter difficulties in « rolling over their debt.« However, the scenario of a local government defaulting seems highly unlikely in China. On the other hand, it seems more likely that a local government in difficulty will devote a significant portion of its cumulative borrowings in 2023 and 2024 to avoiding a liquidity crisis rather than supporting economic activity. This risk could be postponed until 2025, but that would only increase it further at that point.

It should be noted here that this increase in the supply of securities by the GL (via increased bond issuance) does not face a shortfall in demand on the local market. Indeed, structurally high household savings offer ample opportunities to absorb these debts, which limits the risks. The end of deflation is a significant factor in avoiding an increase in the burden of repayments (seebasic mechanism here). However, these factors are secondary to other, more pernicious risks arising from the ambiguous relationship between GL and LGFV.

The thorny issue of opaque links between LGs and LGFVs

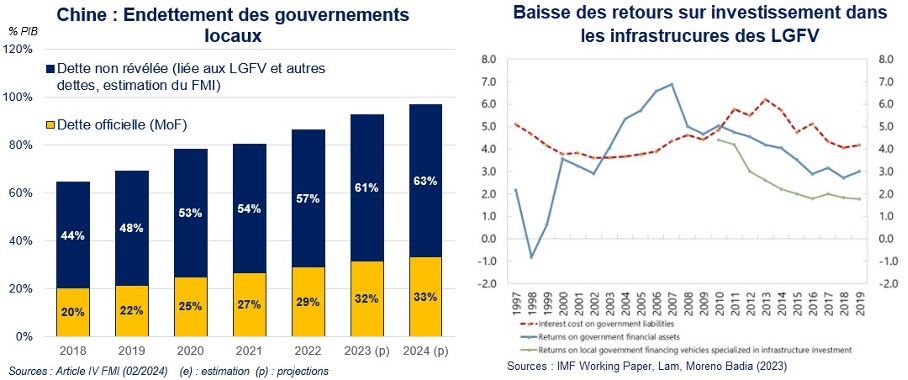

Until now, the analysis has focused mainly on the official debt of local governments. However, the « off-balance sheet » debt of LGs is often cited as a decisive factor in properly understanding the issues surrounding public finances in China. According to estimates, this off-balance sheet debt is anything but negligible and could represent up to nearly double the official debt of LGs. In its 2024 Article IV, the IMF estimates that the « official debt » of local governments reached 32% of GDP in 2023 and that the « undisclosed » portion represented 61% of GDP (see chart below left). This 61% covers a number of commitments made by local authorities, including guarantees (even implicit ones) granted to LGFVs (see Appendix at the end of the article).

Unfortunately, data on LGFVs is very opaque and few of them are actually rated by rating agencies. According to PIMCO, the known debt of LGFVs, i.e., bank loans and LGFV bond debt, is only the « tip of the iceberg. » This is all the more worrying given thatsince the summer of 2023, there has been an increase in payment incidents involving LGFVs, suggesting that these entities are facing a debt servicing crisis[8]. This phenomenon can be explained in particular by the low and declining profitability of their assets (the returns on their infrastructure investments are inherently low, see chart above right), the cost of their liabilities exceeding the return on their assets, and their vulnerability due to the downturn in the real estate sector (see Appendix at the end of the article).

While it is difficult to imagine a GL defaulting on its payments, a series of LGFV defaults seems highly plausible[9]. If this type of credit event affects several LGFVs, could it also affect GLs? Unfortunately, it is difficult to answer this question given three key and interrelated unknowns: (1) the number of highly vulnerable LGFVs and the size of their debt repayments due in 2024, (2) the impact of LGFV defaults on creditors, who are also partners of GLs (banks[10], government funds) and (3) whether or not the implicit guarantee of local authorities will be lifted to manage a cascade of defaults, whether upstream or downstream.

The lack of tangible information makes it impossible to provide initial answers to unknown (1). Regarding unknowns (2) and (3), there are several possible scenarios:

- Scenario without GL intervention: GLs are unable or unwilling to intervene to prevent or respond to an LGFV default. This may be the case if GLs consider that an LGFV default on claims againstshadow bankingplayers does not justify intervention. The lack of intervention may also be motivated by the insignificant cost of restructuring the debt or liquidating the LGFV, both for creditors and for economic activity. To avoid any form of systemic risk, the central bank could also create specific credit facilities to provide LGFVs with liquidity via banks. This option is complementary to the other scenarios outlined below.

- Scenario with upstream intervention by local authorities: In the event of an imminent risk of LGFV default on the bond market, in order to avoid creating a shock wave, local authorities could be called upon to provide liquidity to LGFVs so that they can meet their maturities while continuing to fulfill their economic missions. Such refinancing would limit the risk of a systemic crisis, but the amounts mobilized would necessarily be offset by cuts in GL spending elsewhere, or would automatically cause their deficits to widen. Other modes of intervention are also possible, with a likely lower opportunity cost for GLs in the short term: debt swaps or transfers of liquid assets from GLs to LGFVs.

- Scenario with downstream intervention by local governments:Following the default of an LGFV, local governments can intervene to facilitate the restructuring of the LGFV’s debt with creditors, particularly the banking sector, if the cost assumed by the latter does not generate a high risk elsewhere (particularly in terms of solvency). The case of the restructuring of the Guizhou LGFV default (see ndbp 9) is an example that could be replicated: extension of the maturity by 20 years, reduction of interest rates, and a 10-year grace period for principal repayment. This type of operation necessarily has an impact on the profitability of banking sector assets. However, the impact on their solvency has been more limited sincethe change in banking regulations in February 2023 concerning the reclassification of restructured loans.

A clear need for reform and rebalancing in the future

Rather than being a year of danger, 2024 will be a year of great testing for local governments, where their resilience and ability to sustain growth in a risky environment will be put to the test.

The risk channels are numerous but clearly identified. This calls for close monitoring of the economic situation and a degree of vigilance with regard to the Chinese economy. The current debates on China’s ability to achieve its growth targets and its degree of vulnerability therefore appear legitimate but should not give rise to disproportionate mistrust.

Resolving the off-balance-sheet debt of local governments and LGFVs will be a major area for improvement in order to defuse the public finance situation in China. Similarly, the need to expand the budgetary scope of local governments appears to be a priority and already seems to be part of the authorities’ roadmap. China will also be expected to address other structural issues (demographics, social protection, financial regulation, credit-driven growth model). Whatever the outcome of 2024, China will not be able to avoid major reforms if it does not want to face a new period of turbulence in 2025 or in the medium term.

V.L with the invaluable assistance of Evelyne Banh and Anthony Morlet-Lavidalie

Appendix on the historical link between LGs, LGFVs, and real estate

To escape the downward spiral of the 2008-2009 global financial crisis, the Chinese authorities implemented a broad fiscal stimulus package in which local governments (LGs) played a pivotal role in investing in infrastructure. However, since 1994-1995, LGs have not only been forced to manage their revenues, which rely heavily on the sale of land use rights[12](nearly 35% of total LG revenues, on average during the 2010s), but are also responsible for bearinga large part of the country’s public spending.

In addition, local governments are seeing their borrowing capacity drastically restricted and are therefore resorting to financing vehicles:Local Government Financing Vehicles(LGFVs). LGFVs benefit from guarantees[14]from LGs and use land as collateral to borrow money and thus have the funds necessary to carry out infrastructure development projects and public services.

Initially, LG and LGVF debt was based mainly on loans from the Chinese banking sector. After 2012, while debt continued to increase, a change in trend was observed with greater use of bond issues on the local market on the one hand, and above all through alternative financing methods on the other (shadow banking, outside the banking sector or bond market), which tended to increase the opacity surrounding the structure of their debt.

After several years of strong expansion, the real estate sector is experiencing a slowdown in 2021. This slowdown can be linked to structural factors (demographic in particular, with a deceleration in urbanization) and cyclical factors (tighter regulations on real estate developers’ debt with the introduction of the « three red lines »). The combination of these factors is leading to a fall in prices and sales, followed by serious financial difficulties for real estate developers. This situation is contributing to the non-completion of housing construction, which is generally prepaid (for more information,this summary from the French Treasury providesa very clear and comprehensive overview), and an erosion of demand for new land.

Against this backdrop of falling real estate prices and construction starts, GLs’ real estate-related revenues collapsed, their financing needs increased, and their debt levels rose. In addition, the value of LGFVs’ collateral based on real estate assets deteriorated, affecting their solvency and financial profile.

[1]These revenues are quite difficult to trace by local authorities. Unlike the taxes mentioned in parentheses, revenues from the transfer of usage rights are not directly recorded in the aggregate public balance of the central government and local authorities. These notes fromBNP andtheDGTclearlyshowthe distribution of revenues according to the various public accounts.

[2]The lack of CDUT revenue data for four local governments makes it impossible to include several provinces with a risk that could prove significant in view of other available data: Liaoning, Tibet, and Jiangxi to a lesser extent.

[3]The widening of the deficit is not solely due to the decline in real estate revenues; other factors are obviously at play, such as tax reductions linked to economic activity, inflation, and spending that is increasing at varying rates, etc. However, the analysis presented here, which is based on the transmission of real estate risk to public finances, remains fully relevant, given the weight of real estate-related revenues in total revenues.

[4]One of the most emblematic measures of 2024 is the launch of a campaign to identify viable real estate projects, with a focus on accelerating the delivery of prepaid housing. The « white list »drawn up by municipalities serves as a reference to guide financial institutions in providing liquidity. By the end of February 2024, nearly USD 18 billion had been released as part of this operation. On the demand side, mortgage lending conditions have been relaxed for households, even for the purchase of second homes.

[5]Repayments as a percentage of GDP in 2024 represent 19% in Tianjin and more than 6% in the five other provinces/municipalities mentioned.

[6] »Rolling debt » consists of refinancing maturing debt through new issuances. While interest rates are trending downward in China, higher risk premiums would likely be applied to local governments with deteriorating debt sustainability parameters.

[7]Based on an analysis of the financial parameters of around 100 LGFVs rated by agencies, the lowest-rated LGFVs (BBB- andnon-investment grade) have, on average, a very short debt maturity profile compared to higher-rated LGFVs (A+ to BBB). However, the following criteria do not allow us to draw any general conclusions about a higher level of vulnerability according to rating grades: debt ratios (as a percentage of equity, as a percentage of EBITDA), interest coverage ratio, liquidity ratio (liquid assets to total liabilities), and profitability ratio (ROE and ROA).

[8]The IMF estimates that nearly one-third of LGFVs have had an interest coverage ratio of less than 100% for the past three years.

[9]In this regard, the default in 2023 of LGFV Zunyi Road & Bridge Construction Group Limitedled to a restructuring of its debt, led by the Guizhou GL.

[10]The risk is not neutral for banks,according to PIMCO, as official bank loans to LGFVs account for 15% of total outstanding loans.

[11]Restructured loans are now reclassified without being recorded as non-performing loans, which means lower capital provisioning costs than before.

[12]As a reminder, in China, land remains the legal property of the public sector. By acquiring land use rights, the « new owners » have a lease lasting several decades, which is almost automatically extended.

[13]These factors are described in the chapter of the BSI Economics book « 12 Economic Keys to Approaching 2030, » published by Dunod.

[14]Since 2014, regulations have been tightened in this area and GLs are no longer allowed to provide explicit guarantees to LGFVs.