Download the PDF: the-false-good-idea-of-sovereign-bond-purchases-in-china

In April 2024, a new story emerged in China:Chinese President Xi Jinping expressed his desire for the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) to include sovereign debt buybacks in its toolkit. This information, which went unnoticed in France, nevertheless sparked heated debate. This is an unusual move, especially since the PBoC has so far refrained from resorting to this type of intervention, while central banks in the United States, the eurozone, and Japan have done so extensively over the past decade.

Everything suggests that these purchases of Chinese Treasury bills by the PBoC are a bad idea. This note aims to shed some light on the subject.

What are we talking about?

Asset purchases are now an unconventional but nevertheless essential tool in the arsenal of central banks (CBs). It is important to distinguish between « purchases » and « repurchases »: i) purchases correspond to direct financing by the CB on the primary market; ii) repurchases correspond to indirect financing, where the CB buys securities on the secondary market from commercial banks, which then resell their securities to the monetary institution.

By operating in this way, the CB quasi-explicitly guarantees the liquidity of the securities that can be repurchased. This encourages a decline in sovereign yields, which serve as a benchmark for other interest rates in an economy. In this way, the decline spreads to all interest rates, leading to a lower « interest rate environment. » Bond repurchases thus contribute to a better transmission of low interest rates within the economy and facilitate the financing of economic activity.

In China, these would be repurchases on the secondary market. However, no information is available at this stage to reveal the details of such an operation: which securities would be eligible (including those of local governments)? What conditions would apply (in terms of bond maturity), what volumes, what timeframe?

What is the context?

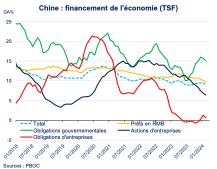

Although only revealed today, the Chinese President’s comments date back to October 2023. At that time, there were a series of negative signals in China: the prolongation of the real estate crisis, the emergence of deflationary pressures,increased monitoring of the debt dynamics of certain provinces, etc. In this context, the authorities announced a strengthening of theirpolicy mix[2], necessary to achieve their GDP growth target (close to +5% for 2023). However, it would appear that despite interest rate cuts, monetary policy transmission is not sufficiently effective, particularly in view of the slowdown in the financing of the economy (see blue and yellow dotted lines in the chart below).

Xi Jinping’s comments make more sense in this context. Bond purchases by the PBoC would in principle complement fiscal stimulus, while also strengthening the accommodative aspect of monetary policy. This would make the famouspolicy mixmore effective and boost activity.

Since October 2023, thepolicy mixhas been strengthened, without resorting to bond purchases by the PBoC. Fiscal stimulus has been based in part on significant bond issuance by the central and local governments (particularly visible in the upward trend of the green curve in the chart above) to support public investment in infrastructure.Interest rate cuts have also been granted.

For 2024, the growth target is similar to that for 2023, and thepolicy mix willonce again be used to boost activity. But does this mean that the PBoC needs to broaden its range of interventions? Nothing could be less certain!

What other tools does the PBoC have at its disposal?

At first glance, the PBoC has many tools at its disposal to steer its monetary policy, and while all of them generally serve specific purposes, none of them currently appear to have reached their limits.

This last point is crucial, given that central banks’ bond-buying policies are mostly taking place in azero-boundenvironment: with lending facility rates (or equivalents) reaching 0%, this floor rate constraint forced central banks to innovate. In this context, they launched securities purchase programs to ease financing conditions and ensure the continued transmission of their accommodative monetary policy. In China, the main reference rates are regularly lowered and remain positive: the one-week reverse repo rate stands at 1.8% and the one-year Medium Long Term Facility Rate (MLF) at 2.5%.The PBoC therefore still appears to have some room for maneuver before needing to resort to a securities purchase policy.

The PBoC can influence both interest rates and the amount of liquidity injected[3]. For example, to increase liquidity and reduce the cost of medium- to long-term operations, it intervenes in the MLF market by: i) by lowering the MLF rate in question (see yellow curve in the chart above left) and/or ii) by injecting net liquidity into this same market[4], regardless of the level of rates, as was the case, for example, at the end of 2023 (see blue areas in the chart above). The PBoC can also usereserve requirement ratios(see chart on the right above), an essential tool in the conduct of Chinese monetary policy, where a reduction in the ratio releases a greater or lesser amount of liquidity, depending on the amounts of deposits managed by the banks concerned.

Is this useful or necessary?

In light of the above, it is difficult to imagine that the PBoC will be led to buy back sovereign debt securities in the short term. The PBoC has always opposed this formore than 15 years, considering this type of policy unsuitable for the Chinese economy and posing a risk to financial stability (risk of price distortion for certain asset classes).

Currently, one of the main challenges for the PBoC is to mitigate downward pressure on the value of the renminbi against the USD, in a context of widening interest rate differentials with the United States. The use of a new monetary policy tool, such as bond buybacks, could be interpreted as a desire on the part of the Chinese authorities to increase the accommodative nature of their monetary policy, without affecting interest rates, in order to preserve, at least temporarily, this interest rate differential with the United States. However, there are two main pitfalls to this argument: i) a bond purchase policy would inevitably lead to additional pressure on the renminbi, and ii) such a choice would probably have serious consequences for the PBoC and cast serious doubt on its credibility and on the usefulness and effectiveness of its conventional tools.

If the PBoC were to give in, it would probably not opt forquantitative easing, as seen in the United States or the eurozone, as the sovereign bond market is far from being under pressure in China:

- Firstly, against a backdrop of low inflation and highly accommodative monetary policy, 10-year sovereign yields are at an all-time low (2.3% and a negative spread compared to US rates of the same maturity at the beginning of April) and other market indicators do not reveal any particular tension.

- The rapid development of a local bond market during the 2010s providesoutlets for local governments wishing to place their debt securities. In addition,benchmark bond indices, such as FTSE Russell, include Chinese onshore sovereign bonds, ensuring easy access to Chinese sovereign securities for foreign investors.

- Extremely high private savings in China andthe lack of a wide variety of financial investments (especially during the real estate crisis) provide powerful leverage to absorb large volumes of sovereign debt without the need for intervention by the PBoC.

- State-owned banks can be called upon to purchase sovereign securities, thereby partially replacing PBoC buybacks, at least temporarily. In this scenario, the macroprudential framework[6]can be adapted accordingly,as was the case in 2018, in order to encourage Chinese banks to purchase central and/or local government debt securities.

There is only one scenario that could require the PBoC to buy back sovereign bonds: if the central government fears that, giventhe significant repayments due from certain local governments in 2024, the emergence of a refinancing risk could lead to a liquidity crisis. In such a scenario, bond debt issuance would be severely constrained, and without intervention by the PBoC to ensure sufficient liquidity, the growth target for 2024 would become unattainable. However, such a scenario seems rather unlikely (see this note for more information). In the coming months, the PBoC’s communications will be closely scrutinized for any change in tone to better understand whether or not it appears ready to enter a new era of buybacks.

[2]Combination of monetary policy and fiscal policy.

[3]For example, if the PBoC seeks to ease financing conditions for mortgages, it will tend to reduce the 5-year Loan Prime Rate.

[4]The PBoC goes beyond refinancing previous financing lines on the MLF market, which consists of a net addition of liquidity to the market.

[5]The 5-year CDS premium has been on a downward trend since 2023 (80 pts below the level of the previous real estate crisis in 2015-2016). In addition, the Shibor rate on the interbank market is also reaching historic lows.

[6]For example, by reducing the capital charge for purchased securities, or by relaxing the eligibility requirements for these securities as collateral for repo/reverse repo transactions, etc.