Usefulness of the article : Following the 2008-2009 crisis, it was the eurozone countries with the highest current account deficits and the largest net external debt positions (e.g. Spain, Portugal, and Greece) experienced the sharpest rise in their public financing costs (sovereign bond yields), linked to concerns among foreign investors in a context of growing public deficits. This publication aims to take stock of current account balances in the euro area and the risks weighing on the sustainability of net external investment positions.

Summary:

- Compared with their pre-crisis levels in 2008-2009, current account deficits in the euro area have fallen considerably: while in 2007, the combined deficits of eurozone countries amounted to 2.2% of eurozone GDP, they are only 0.5% for the period from July 2021 to June 2022;

- However, eurozone countries are facing two negative shocks to their current account balances: the end of the health crisis (its effects on international trade and tourism) and, above all, the rise in hydrocarbon prices resulting from the war in Ukraine. While all eurozone countries are exposed to these shocks, their degree of exposure differs from one country to another. The duration and intensity of the shock will likely play an important role in measuring the vulnerability of current accounts.

- Cyprus is in a particularly worrying situation, with a structurally high current account deficit (5.6% of GDP in 2019); In Greece, the current account deficit is also high, but this is more attributable to the two ongoing shocks. In Malta, Slovakia, and Latvia, the current account balance could remain far from equilibrium for some time, depending on the current shocks, but should converge towards equilibrium if the situation returns to normal.

French version:

English version:

English version:

Current account imbalances[1]can be a major driver of economic crises, particularly, but not exclusively, in developing countries. As such, they are closely monitored by the International Monetary Fund. For example, the accumulation of substantial current account deficits leads to a rapid deterioration in the net international investment position (NIIP) – the difference between financial assets and liabilities vis-à-vis non-residents. When the deterioration in the NII appears too rapid to be sustainable, foreign investors may doubt the recipient country’s ability to repay them and therefore withdraw some of their financing offers.

The southern euro area countries, which recorded large current account deficits in 2008, had caused concern among foreign investors, who restricted their financing offers in 2010-2012, contributing to the rise in these countries’ sovereign financing costs. This publication focuses on eurozone countries whose current account imbalances cannot be corrected by exchange rate movements, as the euro exchange rate is determined at the eurozone level.

While a significant rebalancing of current accounts followed the euro area crisis (2010-2012), the health crisis and the war in Ukraine are contributing to a deterioration in the euro area’s current accounts. The health crisis is having an impact through three channels: (i) the slowdown in foreign trade (linked to bottlenecks in countries taking the most restrictive measures, such as China), (ii) the reduction in transport flows, and (iii) the decline in tourist flows. The southern eurozone countries, which are the largest net exporters of tourism services, have been and remain the most affected by the health crisis[2]. At this stage, the war in Ukraine has mainly affected current accounts through the channel of commodity prices (particularly oil and gas).

What is the current status of current account balances in the euro area?

1) Current account balances in the northern eurozone remain solid

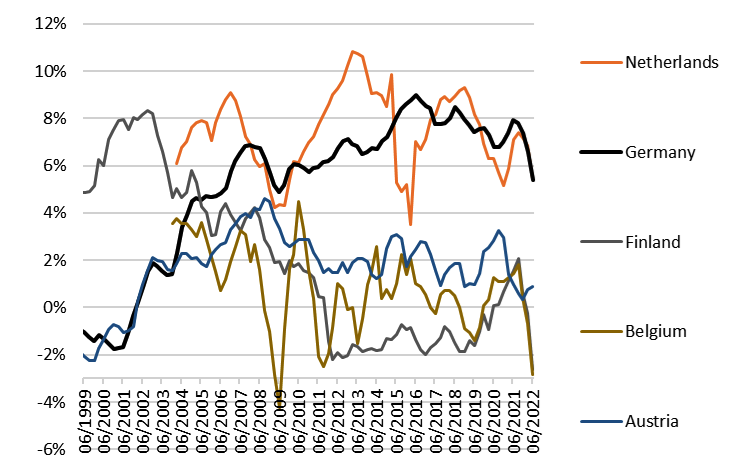

In the northern eurozone countries, current account balances are expected to remain solid, with only two of them running current account deficits due to higher gas and oil prices.

Germany and the Netherlands still recorded current account surpluses of more than 5% of their GDP, mainly due to their goods balance. Over the period from July 2021 to June 2022, Austria’s current account balance is close to equilibrium, while Belgium and Finland have slight deficits. Luxembourg and Ireland have large current account surpluses that are subject to significant short-term fluctuations linked to their balance of services or income: given their high level of financial assets and liabilities vis-à-vis the rest of the world, a slight change in the return on their international assets or liabilities can have a significant impact on their income balance.

Chart: Current account balance (% of GDP) in five northern euro area countries

Source: Eurostat

Despite the healthy state of their current accounts, the northern euro area countries have been affected to varying degrees by the war in Ukraine. Between 2021 and the period from mid-2021 to mid-2022, the balance of goods has already deteriorated by 1.4 percentage points of GDP in Germany and 3.2 percentage points of GDP in Belgium, mainly due to the increase in the value of their hydrocarbon imports. With gas and oil prices remaining high, this is likely to contribute to an even greater deterioration in their goods balance over the whole of 2022. However, this effect is expected to remain largely temporary.

2) Thanks to the reduction in current account deficits, only two countries in Southern Europe are in a worrying situation

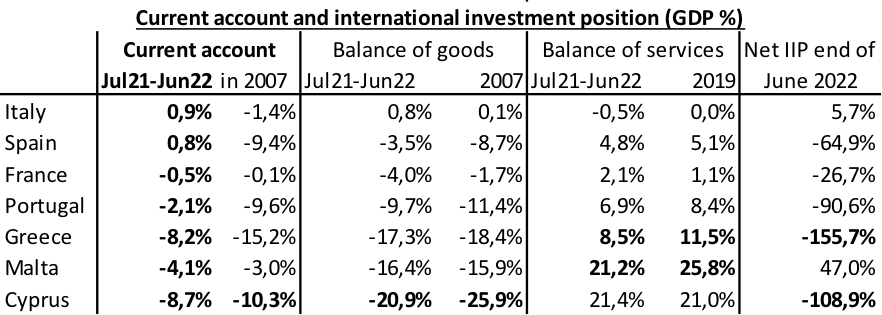

A group of countries in the southern euro area had current account balances close to equilibrium in 2019, but these have since deteriorated due to the impact of COVID-19 on tourism and transport and the rise in oil and gas prices since the end of 2021.

The extent to which Italy, Spain, and Portugal have improved their goods balances since 2007 is notable. Conversely, France’s goods balance deficit has continued to grow slowly. In Spain, Italy, and France, the long-term balance of the current account should not be jeopardized by rising oil and gas prices, as this shock is likely to be temporary. In France, the current account balance (-0.5 percentage points of GDP) remains supported by a surplus in the services and income balances, which almost offsets the goods balance deficit (-4 percentage points of GDP). The size of Portugal’s current account deficit in 2022 will depend on how long oil and gas prices remain high and on the potential rebound in its revenues from non-resident tourists.

In Malta, Cyprus, and Greece, the goods balance and current account balance remain clearly in negative territory, despite a significant improvement since 2007 in the latter two countries.

Source: Eurostat

Greece, Cyprus, and Malta have current account deficits of more than 4% of their GDP, but are in structurally different situations. In Malta, the deficit is limited to 4.1 percentage points of GDP, almost exclusively due to the deterioration (-3.7 percentage points of GDP) in its travel balance compared to pre-COVID levels. In Greece, the deficit stands at 8.2 points of GDP, but two points of this can be explained by the deterioration in the travel balance since 2019 and 2.7 points by the deterioration in the goods balance since 2021 due to the increase in its hydrocarbon imports. Cyprus’s current account deficit (8.7 points of GDP), on the other hand, appears to be more structural, with only one point attributable to the deterioration in the travel balance since 2019 and 2.9 points to the deterioration in the goods balance compared to 2021. It should be noted that these countries’ travel balance rebounded in the second quarter (Q2) of 2022 compared to Q2 2021, suggesting that this rebound may continue in Q3 2022.

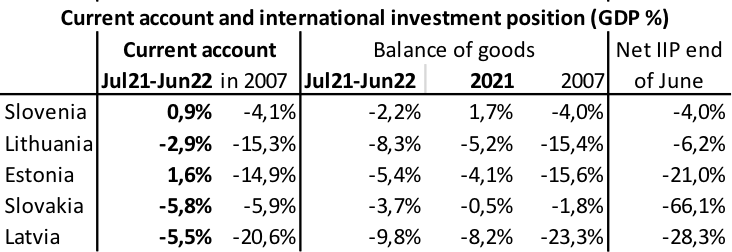

3) The reduction in current account deficits is also notable in Eastern European countries, but the war in Ukraine has worsened the situation in several of them

Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia have significantly improved their current account balances since 2007 due to a significant reduction in their goods account deficits. Slovenia has done the same, but to a lesser extent and by one-third through mineral products (including hydrocarbons).

During the last observable period (July 2021–June 2022), the current account balances of Slovenia and Estonia are close to equilibrium, while Slovakia and Latvia are running significant deficits (above 4% of GDP), with Lithuania’s deficit being more moderate (-2.9 percentage points of GDP).

In Slovakia, Latvia, and Lithuania, the current account deficit is expected to continue to widen in 2022 as a result of the increase in the value of their mineral fuel imports, which has already led to a substantial deterioration in their goods balance compared to 2021. Nevertheless, given their growth potential, these countries should be structurally capable of maintaining their current account balance at a level that does not worsen their net external position in terms of GDP points.

Furthermore, in Slovenia, which has a current account surplus of 0.9 percentage points of GDP (see table below), the deterioration of 3.9 points of GDP in the goods balance between 2021 and the period from mid-2021 to mid-2022 is attributable to an increase in imports not of hydrocarbons but of other categories of goods, including means of transport.

Source: Eurostat

Graph: current account balance (% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat

Conclusion

The scale of the reduction in current account deficits since 2007 is striking in both Southern and Eastern Europe. However, COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine have led to the reappearance of significant current account deficits in ten eurozone countries, including three in Eastern Europe and five in Southern Europe. The situation is worrying in Greece and especially in Cyprus, where the current account deficit is only marginally linked to the two recent shocks.

Alain Carbonne

[1] For the record, the current account tracks all current flows (goods, services, and income) between resident and non-resident agents. Incoming payments (e.g., those from export revenues) are recorded with a positive sign.

[2] For example, Malta’s tourism balance is currently 3.7 percentage points of GDP below its 2019 level.