Purpose of the article: This article aims to (i) explain the mechanisms of quantitative tightening and (ii) present the channels through which this measure can affect financial markets.

Summary:

- In the wake of its key interest rate hikes, the Federal Reserve (Fed) has begun to reduce its balance sheet. The latter shrank by more than USD 300 billion between June and November 2022.

The Fed’s quantitative tightening is being carried out by not reinvesting maturing Treasury bills and MBS[1].- This restrictive monetary policy measure could lead to higher medium- and long-term rates, and even higher short-term rates in the event of liquidity stress.

In 2022, most central banks began tightening their monetary policy to combat record inflation. The Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank (ECB), and the Bank of England (BoE) raised their interest rates by 375, 200, and 300 basis points, respectively.

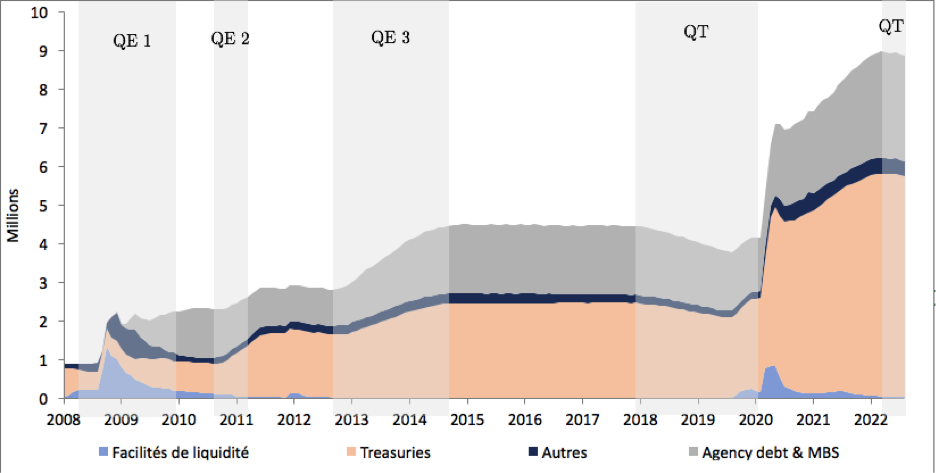

Monetary tightening also involves reducing the purchases of assets that have been accumulated on central banks’ balance sheets since the 2007-2008 financial crisis and the Covid-19 crisis. The Fed began its quantitative tightening in June 2022, reducing its balance sheet by a maximum of USD 47.5 billion per month, then by USD 95 billion from September onwards. The BoE also began reducing its balance sheet in November. As for the ECB, it will clarify in December the outlook for its quantitative tightening, which is expected to begin in 2023.

While quantitative tightening is currently overshadowed by rising key interest rates, it could have an impact on financial markets as it is rolled out. It is therefore important to understand (i) how this monetary policy instrument works and (ii) what its effects on financial markets could be.

1. How do central banks reduce the size of their balance sheets?

Quantitative tightening, the opposite of quantitative easing , is a restrictive monetary policy measure that aims to reduce the size of central banks’ balance sheets. This measure should be distinguished from tapering , which only stabilizes the size of the balance sheet. The objective of quantitative tightening is to exert downward pressure on long-term interest rates by reducing the excess liquidity that has accumulated in recent years. While most central banks have implemented quantitative easing programs, only the Fed experimented with quantitative tightening between 2017 and 2019.

There are two ways to reduce the size of central banks’ balance sheets:

- The most intuitive is the direct sale of securities on the central bank balance sheet (active management).

- The second is not reinvesting securities that reach maturity (passive management).

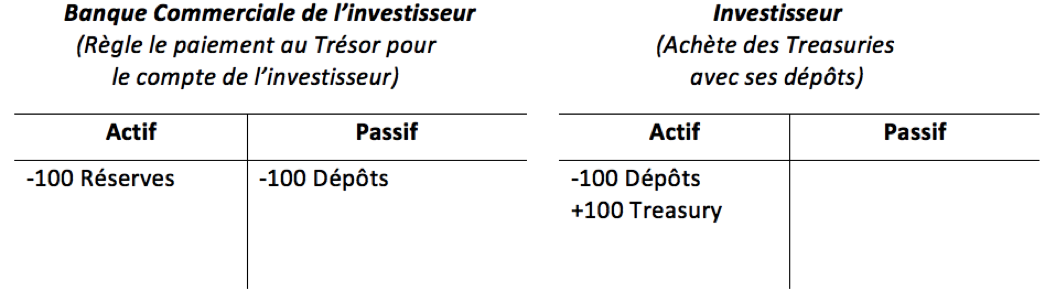

The Fed used this second option during its previous quantitative tightening and is doing the same today. It works as follows: when a bond matures, the central bank recovers the redemption value. Rather than reinvesting this amount in the purchase of a new bond (as it did previously), it destroys the corresponding currency on the asset side of its balance sheet. In accordance with the double-entry accounting principle, this action must also be reflected on the liability side. This involves reducing commercial bank reserves. In this way, it destroys the excess reserves it has created (by purchasing securities from banks as part of quantitative easing). Ultimately, quantitative tightening reduces the central bank’s balance sheet and the level of commercial bank reserves, and changes the composition of investors’ balance sheets (see illustration below).

Illustration 1: Simplified changes to balance sheets following the non-reinvestment of a Treasury bond by the Federal Reserve

To ensure a gradual reduction in the balance sheet, the Fed sets limits on the monthly amounts of maturing securities that are allowed not to be replaced. Amounts exceeding the cap will be reinvested and retained on the balance sheet. For example, if the Fed receives USD 40 billion in redemptions of maturing securities but limits the pace of quantitative tightening to USD 20 billion per month, it will only reinvest the USD 20 billion difference. It is also possible that redemptions will be significantly lower than the caps set. The Fed’s current monthly caps are $60 billion for Treasury bills and $35 billion for MBS. Thus, the Fed’s balance sheet is shrinking by a maximum of $95 billion per month.

Figure 2: Change in Fed balance sheet assets between January 2008 and August 2022 (in USD billion)

Source: Bloomberg, BSI Economics

The Fed has not completely ruled out resorting to active quantitative tightening[5] through the sale of MBS. There are two reasons for this:

· The central bank ultimately wants to hold only government bonds on its balance sheet.

· MBS are characterized by long maturities (30 years on average). With 30-year mortgage rates having doubled in recent months, the majority of MBS securities on the Fed’s balance sheet will not mature for a long time. This is because homeowners have little incentive to refinance their mortgages now and may be more reluctant to move. This means that investors (the Fed) are seeing their principal payments come in more slowly than in previous years. Selling MBS could therefore be a solution to reduce the amount of MBS on the Fed’s balance sheet.

2. What are the effects of quantitative tightening on the markets?

While the effects of quantitative easing have been extensively studied and demonstrated, those of quantitative tightening are still largely uncertain. As stated above, there has only been one experiment with quantitative tightening to date, and it lasted only two years. Some economists (Smith & Valcarcel 2022[7]) have provided empirical evidence that the effects of quantitative easing and tightening are asymmetric. Below, we present the theoretical effects of quantitative tightening. It is important to note that the magnitude of these effects remains unknown at this stage and depends on a large number of parameters.

Quantitative tightening, through the reduction of commercial bank reserves, can exert upward pressure on short-term interest rates. This effect is not linear but can occur when the total amount of reserves in circulation approaches the minimum level required by banks. This type of stress can even lead to a liquidity crisis when banks’ reserve requirements are not met, causing, in particular, an increase in interest rates on the interbank market.

For example, during the Fed’s first quantitative tightening between 2017 and 2019, a liquidity crisis occurred in the repo market. In September 2019, banks faced a freeze in the US interbank market and abnormally high rates in the repo market. This situation led the Fed to intervene massively in the market as a lender of last resort and to restart its quantitative easing program in order to add the reserves needed to keep the system functioning properly. The chart below shows the evolution of the SOFR[9] (Secured Overnight Financing Rate) and the central bank’s response, illustrated by the total amount of assets on its balance sheet, which rose again following the liquidity crisis in the interbank market.

Figure 3: SOFR and total Fed balance sheet assets between May 2018 and November 2022

Source: Bloomberg, BSI Economics

Furthermore, quantitative tightening may impact the medium- and long-term segments of the yield curve. All other things being equal, reduced demand for securities from the US central bank will lead to an excess supply of securities. Given the inverse relationship between prices and interest rates, interest rates are therefore likely to rise. This excess supply of securities will have to be absorbed by the private sector, leading to higher risk and term premiums. In addition, another channel that accentuates this upward movement in medium- and long-term rates is the signal channel. The reduction in the balance sheet sends a signal of future monetary tightening and therefore an upward adjustment in key interest rate expectations.

These upward pressures on rates could be even greater in the MBS market. Compared to Treasury bills, MBS are traded less frequently and demand for them is lower. In 2022, we saw the sharpest rise in mortgage rates and the sharpest rise in MBS yields ever recorded. The Fed’s gradual withdrawal could continue to put pressure on this market. This would be accentuated if the Fed decided to start selling MBS, an option that cannot be entirely ruled out, as explained above.

Conclusion

In the current environment, the Fed’s balance sheet reduction is not the main driver of Treasury bond yield movements. Short-term Treasury bills largely reflect the trajectory of short-term rates, i.e., investors’ expectations regarding the pace of key rate hikes and the Fed’s terminal rate. Longer-term Treasury bills also factor in the longer-term economic outlook.

In addition, the Fed is conducting its balance sheet reduction in a highly predictable and transparent manner so as not to cause a sharp reaction in financial markets. Thus, while quantitative tightening appears to be having little impact on markets to date and is operating in the background of the rise in key interest rates, it is important to consider the risks outlined above.

As quantitative tightening reduces the level of reserves, the risks of market reactions increase. Implementing balance sheet reduction therefore involves striking a delicate balance between withdrawing liquidity from the system and not destabilizing financial markets.

[1] Mortgage-backed securities.

[2] An expansionary monetary policy measure whereby a central bank buys up financial assets on a large scale in order to inject liquidity into the economy, facilitating the transmission of monetary policy when interest rates are at rock bottom and thus stimulating economic growth.

[3] Commercial banks’ cash deposits in their central bank accounts, which appear on the assets side of their balance sheets. There are two types of reserves: (i) required reserves and (ii) excess reserves, which correspond to the amount of commercial banks’ reserves deposited with the central bank in excess of legal requirements.

[4] When the Fed purchased securities, it paid the selling bank by increasing its excess reserves by an amount equal to the purchase price of the security.

[5] Fed minutes from March 2022: « Participants generally agreed that after balance sheet runoff was well under way, it will be appropriate to consider sales of agency MBS to enable suitable progress toward

a longer-run SOMA portfolio composed primarily of Treasury securities. »

[6] « I would just stress how uncertain the effects are of shrinking the balance sheet, » Jerome Powell (May 4, 2022)

[7] Andrew Lee Smith & Victor J. Valcarcel, 2021. “The financial markets effects of unwinding the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet,” Research WP RWP 20-23, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City

[8] Repos, or “delivered pensions,” are very short-term loans—often overnight—between financial institutions, which are secured by government bonds, or Treasuries. A bank will buy a bond from a manager for cash, committing to sell it back at a specified price and date.

[9] This rate measures the cost of overnight borrowing through repurchase agreements secured by U.S. Treasury securities.

[10] Highest interest rate before the Fed began its monetary policy « pivot, » i.e., lowering its key interest rates.