New risks and management requirements for multinational companies

Summary:

– The globalization of trade and capital flows, as well as the integration of emerging countries into these flows, have led to renewed interest in these markets on the part of multinational companies, despite the risks they present.

– Multinational companies must therefore develop techniques for identifying and analyzing country risk in order to quantify it and guide their development and investment strategies.

– Multinational companies can hedge against international risks and also mitigate their exposure to these risks.

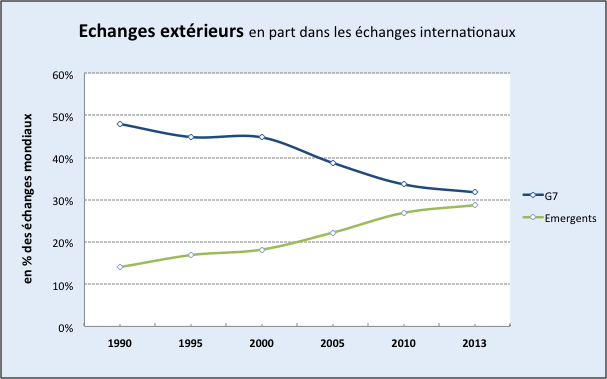

The internationalization of trade is reflected in the integration of new « emerging » countries that participate in these flows. While emerging countries[1]accounted for only 14% of global international trade (imports and exports) in 1990, they now account for 29%. Over this period, the share of G7 countries fell from 48% to 32% of global trade.

Figure 1. Change in the share of G7 countries and emerging countries in international trade between 1990 and 2013:

Source: author, WTO, Macrobond, BSI Economics

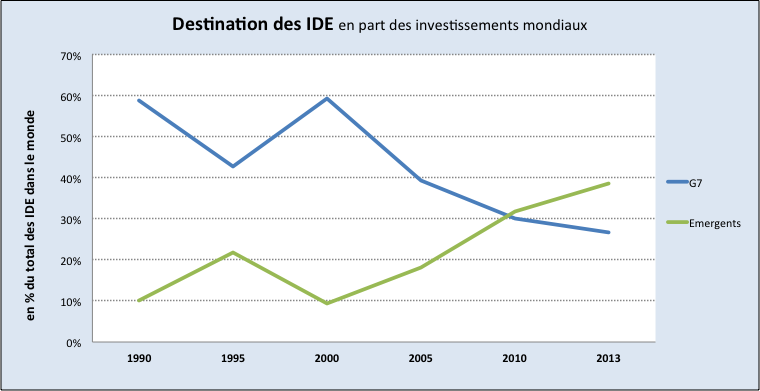

The internationalization of capital movements is a major challenge for countries seeking to attract FDI. Such investments enable emerging countries to benefit from technology transfers and secure the development of local businesses. Some countries (Brazil, China, Russia, Turkey, Indonesia) are beginning to move upmarket in the production of goods and services for their domestic and export markets. These emerging countries are rapidly expanding markets for international companies, as evidenced by the evolution of global FDI flows, which are now mainly directed towards emerging countries (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Evolution of FDI flows to G7 countries and emerging countries between 1990 and 2013:

Source: author, World Bank, Macrobond, BSI Economics

Whether to extract raw materials, invest in new markets, or relocate production activities, multinational companies are expanding their operations in new countries that may be less stable economically and politically.

Country risk can be defined as the quantification of the probability that an event occurring in a country will have a negative impact on a company’s activities. Country risk analysis is a decision-making tool that compares the risk and return of an investment.

By internationalizing their production, shareholding, and target markets, companies increase their exposure to the risks inherent in the countries in which they operate. The UNCTAD transnationality index (which measures a company’s share of foreign assets, foreign jobs, and foreign sales, Figure 3) shows a gradual increase in the geographic diversification of multinational companies’ activities during the 2000s.

Figure 3. Evolution of the TNI index 2004-2008:

Companies’ exposure to international risks

1 – Political and legal risk

Political risk is the risk that a decision taken by a government may have a negative impact on a company’s activities. Military conflicts can have a direct impact on certain companies operating in territories affected by material destruction and market losses, as well as indirect repercussions via commodity prices, international transport, or the imposition of economic sanctions.

There is also the risk of non-recovery of receivables following government intervention. Sovereign defaults (Argentina 2001 and 2014) and nationalizations, particularly in the raw materials sectors (YPF in Argentina, PDVSA in Venezuela), are common in emerging countries. These risks require a company to familiarize itself with the political and military environment of the country in which it operates.

In addition, respect for contract law is a major factor in assessing risks in a country. An unstable legal environment can be very destabilizing for a company: the lack of independence of the courts (China), the differential treatment of creditors (national preferences in Kazakhstan), radical changes in regulations (raw materials in Indonesia), for example.

2 – Economic and financial risk

Economic risk is similar to assessing a country’s financial capacity and the impact of economic conditions on a company’s business. The onset of an economic crisis may initially affect a company indirectly by impacting its partners. An importing company that depends on a foreign supplier may find itself unable to obtain the product it wishes to import if an economic crisis weighs on the economic activity of the exporter’s country.

A multinational company may see some of its subsidiaries affected by market risk in a country in crisis. A poor economic climate impacts private consumption and government orders, and creates a risk for companies producing goods and services for this market.

The deterioration of the economic situation in a country can have other repercussions on multinational companies via price levels, taxation, or the banking sector. In the event of deflation, a company producing goods and services for the affected country sees its margins reduced as a result of lower revenues and stable costs. In the case of high inflation, the price of imported products increases, which also weighs on the company’s margins.

The government of a country whose economic situation has deteriorated may decide to raise taxes to limit the deterioration of its budget balance. Thus, tax increases for economic reasons will directly impact the results of the company or subsidiary operating in the country.

Financial risk is the risk for companies of facing volatility in exchange rates, interest rates, or stock markets in a country. These are risks that arise from the country’s economic situation and developments in international capital markets that determine the movement of investment flows.

Companies with high short-term debt denominated in foreign currency may see the value of their external debt rise sharply as a result of the appreciation of the currency in which the debt is denominated. Conversely, currency appreciation, by making domestic products more expensive relative to foreign products, will undermine the price competitiveness of exporting companies.

Whether through key interest rates (to deal with a credit bubble or currency appreciation) or risk premiums (linked to the perception of risks in a country), companies operating in emerging countries may face significant volatility in (re)financing conditions.

3 – Other categories of risk

Environmental risk is not new in nature, but rather in our perception of the effects of industrial production on the environment. Recent international regulations in this area attempt to make companies aware of the effects of their activities on the environment. In addition to damage to the environment, these risks can have financial repercussions for a company, such as project failure, damage costs, and legal penalties depending on the country.

This risk is also closely linked to another risk, namely reputational risk. A company’s reputation is considered an « intangible asset, » most often linked to an iconic brand. Based on an estimate of future earnings from the use of the brand name, a company’s reputation can reach very high values. Reputation can also help cushion losses in the event of a negative event (confidence-based crisis management following the BNP Paribas fine). It is therefore essential for a company to preserve its reputation. Issues related to the environment, human rights, hygiene, or fraud (criminal, financial) are very important here because they can impact a company’s reputation. As such, companies’ SRI approach is increasingly valued as intangible capital on their balance sheets, prompting them to direct their investments towards countries with strong institutions. Oekom’s SRI rating, based on social and environmental criteria, is now particularly closely followed.[2].

Identify, quantify, hedge, and mitigate country risk

1 – Country risk analysis

Country risk analysis enables investors to manage their investment strategies. Each investment is guided by risk and return calculations, made possible by information provided by analysts. Depending on each investor’s risk threshold, the decision to invest is based on the ratings given to each country. Ratings are tools for analyzing changes in risk in a country. For investors who choose to set up operations in a country, the rating provides real-time information on, for example, changes in the investment code, conditions for repatriating capital, etc. It also provides insight into the country’s solvency. Ratings are used to determine country risk premiums. It is important to differentiate between country risk and sovereign risk. The former encompasses all the economic, social, and political risks that make up the business climate in a country. Sovereign risk relates solely to the ability and willingness of states to honor their creditors.

Country risk analysis is a tool for decision-making and reducing uncertainty. It guides investors, exporters, and banks in their choices based on their preferences regarding the trade-off between risk and return. Each company should establish constraints and impose limits based on these analyses. The riskiest countries may remain attractive to investors who are well covered (insurance, forward contracts) or who are looking for high returns (higher risk premiums in emerging countries are therefore more lucrative). A company’s assessment of the risks in a country depends above all on its visibility of economic and political conditions. A dynamic but unstable country will be considered riskier than a country where growth prospects are weak but medium/long-term visibility is better.

2 – International risk hedging techniques

A multinational company can choose so-called internal hedging. A company’s geographical and productive diversification allows it to limit its sensitivity to the situation of a country in its production chain or destination markets.

Certain guarantee techniques between the parent company and its subsidiaries also enable multinational companies to hedge against the risk of non-payment. Similarly, making debt repayment flows more flexible in line with changes in the exchange rates in which these transactions are denominated helps to mitigate currency risk.

Multinational companies can also use external hedging. These are paid insurance policies taken out with public or private insurers or on the financial markets. They consist of a paid transfer of risk and, as such, influence the return on a transaction. Private insurers, whose role is to « support corporate strategies around the world, » cover exporters against the risks of market disruption, non-payment, non-transfer, and abusive calls on guarantees. For importers, the risks of non-delivery, contract termination, and non-repayment are covered. Some insurance policies also cover investment-related risks: confiscation, expropriation, nationalization, dispossession, non-transfer of dividends and receivables, physical damage, and business interruption. Several insurers also specialize in risks related to the expropriation of personnel, such as kidnapping, expulsion, forced repatriation, etc.

Exporters can also go through export credit agencies. Most countries have an agency or an import-export bank that insures the most difficult risks, thereby promoting the export of domestic companies abroad and attracting FDI. Export credit insurers offer payment guarantees to investors, thereby recovering a large part of the risk of the covered transaction.Export credit agencies(ECAs) can also make direct loans to companies at below-market interest rates.

Finally, it is possible to hedge against other risks, such as currency, credit, or interest rate risk, using derivatives, forward contracts, or insurance purchases and other financial market products (swaps, CDS, CDO, etc.). However, the very high cost of this coverage weighs on the return on investment, so it is sometimes preferable to choose internal coverage or to go through export credit agencies.

3 – How can the political and economic risk of international investments be mitigated?

To mitigate their exposure to political risk abroad, multinationals can form a joint venture with a local company. In this agreement, the two companies pool their comparative advantages to be more competitive in a market. For example, a foreign company forming a joint venture with a local company will benefit from low labor costs, access to raw materials, operational distribution networks and local factories, and market experience (culture, business customs, contacts, regulations, etc.). In exchange, the local company benefits from technology transfer from the investing company. It is very important for emerging countries to be able to capture the technology of large multinationals through the formation of joint ventures. By adopting a « good citizen policy, » i.e., highlighting the benefits they bring to the host country in terms of jobs, technology, and other positive externalities, foreign companies can nurture their relationships with national authorities and thus limit political risk.

The direct acquisition of a foreign company may seem economically relevant. Greater management flexibility allows the parent company to benefit from the structures and networks of the local company without the risk of management conflict or technology theft. However, many emerging countries are putting barriers in place to prevent foreign companies from owning local companies: Algeria requires foreign companies to partner with a local company in order to develop their business in the country, while in Qatar, all companies must be majority-owned by Qatari shareholders.

Conclusion

It is important to distinguish between two broad categories of industries, depending on whether they are more or less capital-intensive. Because they hold more assets in risky countries, capital-intensive industries are more exposed to political risk than less capital-intensive companies. For example, financing an infrastructure project (such as a dam, airport, etc.) requires very large amounts of money over long periods of time, which exposes foreign companies to even greater country risk. Conversely, a less capital-intensive company specializing in the marketing of cosmetics will not have as many assets exposed to economic and political risks in a foreign country.

Country risk manifests itself in very different ways depending on the sector in which companies operate (tourism, raw materials, luxury goods, etc.). International companies must be able to assess the variety of political, legal, economic, financial, and other risks that may impact their activities. However, risk management in all its dimensions (analysis, quantification, hedging) is largely delegated to large international investment banks and export credit agencies that have developed real expertise in this area. A better understanding of political and economic environments facilitates risk management and promotes the development of commercial and financial activities in emerging countries.

The 2000s were very favorable for emerging countries, as they benefited from significant capital inflows due to both low interest rates and a flight from risk following the collapse of the real estate markets in the US and sovereign debt in Europe (since 2008). However, the announcement of the end of quantitative easing (and the prospect of interest rate rises) by the US Federal Reserve had the effect of redirecting international capital towards the US, to the detriment of emerging countries, whose currencies fell sharply in 2013 (Turkish lira, Brazilian real, South African rand, etc.). The return of risk aversion in emerging countries therefore had an immediate negative impact on investment in these countries, especially given that their economic fundamentals remain fragile (high current account deficits in the countries mentioned).

References:

– Tamara Bekefi and Marc J. Epstein, Integrating social and political risk into management decision-making, Management Strategy Measurement, Society of Management Accountants of Canada, 2006, 49 pages

– Fouazi Boujedra, Country risk and foreign direct investment in developing countries. Theoretical and empirical analysis, Research paper, No. 2007-4, Laboratoire d’économie d’Orléans, 2007, 21 pages

– Fouazi Boudjera, Country Risk, FDI and the International Financial Crisis: Evaluation and Empirical Study, Research Paper No. 2004-12, Laboratoire d’économie d’Orléans, 2004, 53 pages

– Jo Jakobsen, Political risk for multinational companies, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2011, 46 pages

– Nicolas Meunier and Tania Sollogoub, Économie du risque pays(Economics of Country Risk), Paris, La Découverte « Repères, » 2005, 124 pages

– Bernard Sionneau, Country risk and international forecasting: theory and applications, Doctoral thesis, CNAM, 2000, 769 pages

Notes:

[1] Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, South Korea, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and Turkey.