Summary:

– Sovereign bond yields in many economies followed similar trends in 2013. They rose, sometimes significantly, with discussions about the possibility of the Fed tapering its quantitative easing program appearing to be a trigger.

– There appear to be many different channels that could explain these common variations.

– In some cases, this rise in rates was not in line with the local economic situation, requiring monetary authorities to be particularly vigilant in order to ensure adequate financing conditions and potentially creating difficulties for economic policy decisions.

Since May 2013, international bond markets have been experiencing significant volatility, largely linked to discussions about the Fed’stapering of its securities purchase program and its actual implementation, which was decided at the Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting in December 2013. Long-term interest rates in both advanced and emerging economies rose sharply in the second half of last year. This bond shock was mainly due to the rise in US sovereign rates. After presenting these developments, this contribution aims to outline some of the transmission channels that may affect international bond markets and draw conclusions for economic policy.

1. The rise in long-term US bond yields has had a knock-on effect on other bond markets

The rise in long-term US interest rates in 2013 spread to other economies, both advanced and emerging, contributing to a tightening of financing conditions in these countries.

a. In emerging economies

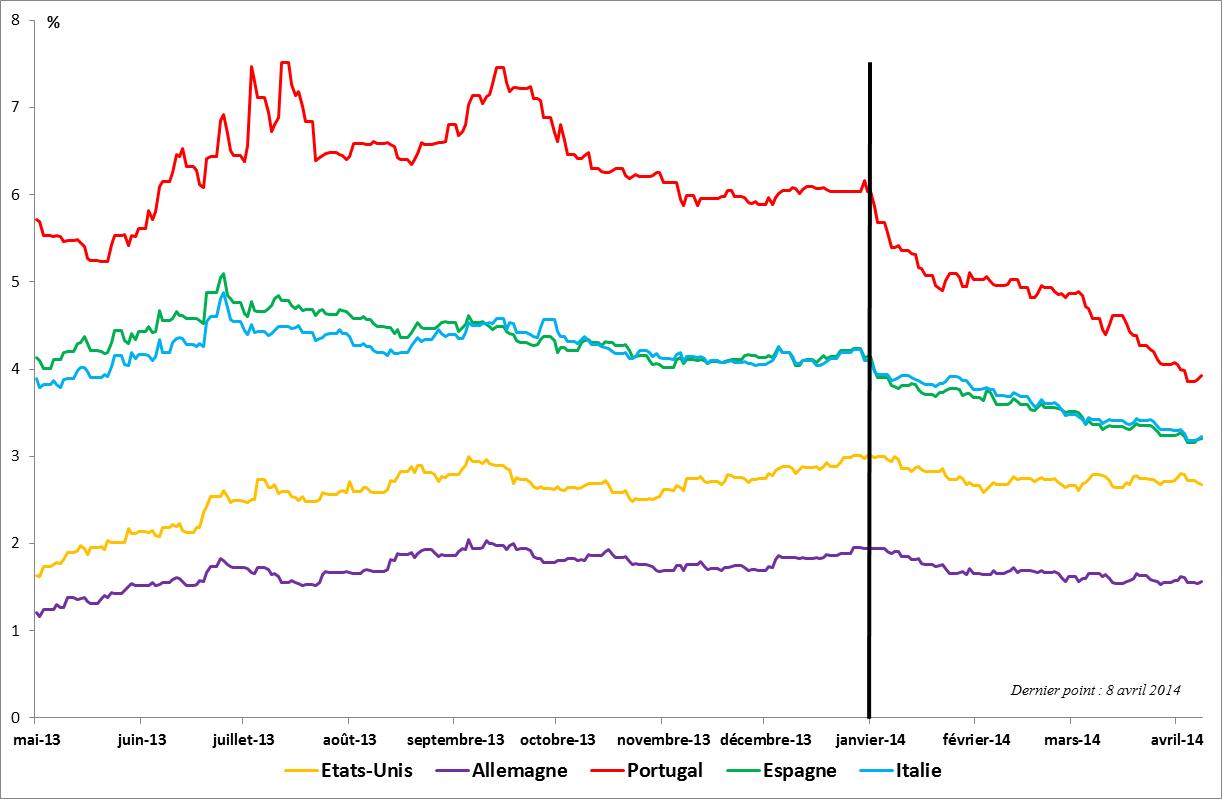

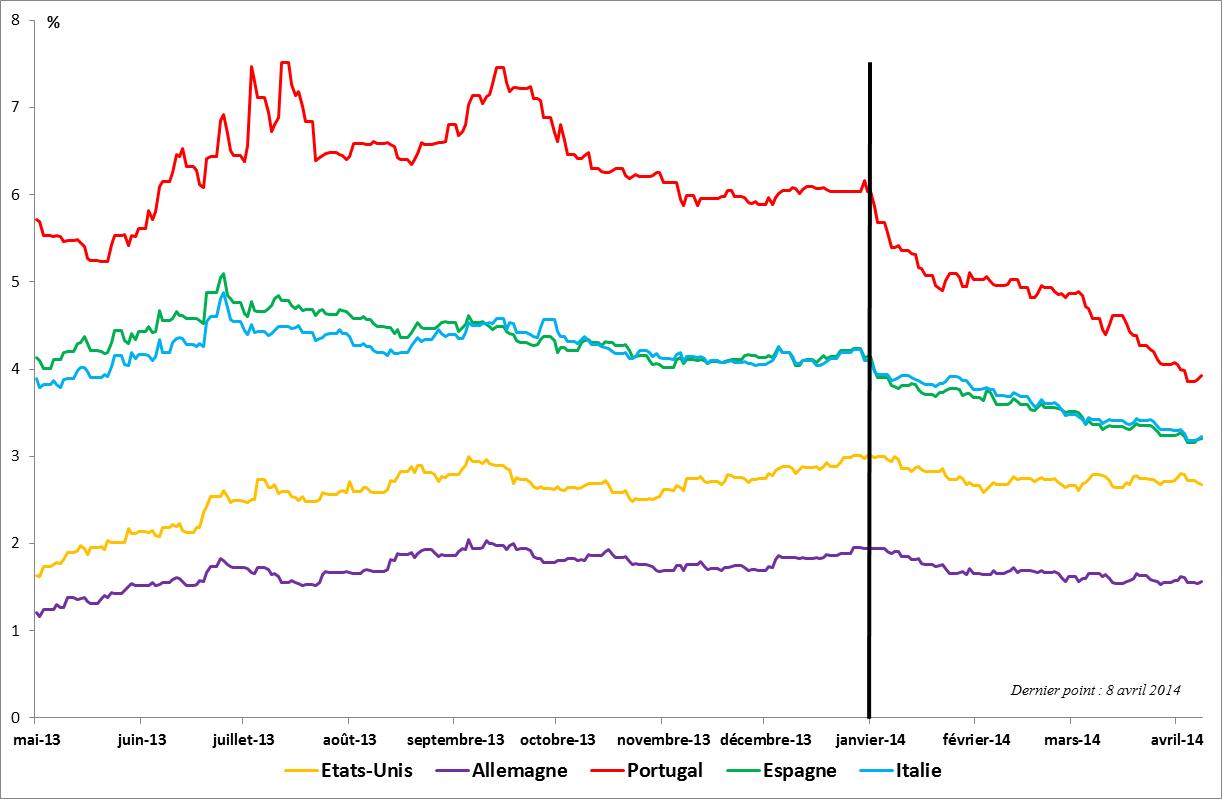

Emerging economies suffered the most from this transmission of higher interest rates, which was particularly marked in the summer of 2013. For example, Brazilian 10-year sovereign rates rose by 361 basis points between May 1 and December 31, including 224 basis points between May 1 and August 31. Indonesian sovereign rates rose by 289 bps between May 1 and December 31, while Korean rates rose by 79 bps over the same period.

These developments led to disruptions in both capital flows to emerging economies and exchange rates. Faced with the perceived increase in risk in emerging economies, some investors sought to reduce their exposure to emerging countries, leading to capital outflows or lower capital inflows. This dynamic can cause depreciation. In 2013, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Turkey, and South Africa experienced sharp depreciation (between 13% and 23% against the US dollar). While US rates fell in the first quarter of 2014, the rise in sovereign rates in emerging economies also slowed, although the crisis in Ukraine did cause rates to rise in some countries, particularly Russia.

Chart 1: Changes in sovereign rates in emerging economies (maturity: 10 years)

Sources: Macrobond, BSI Economics

b. In advanced economies

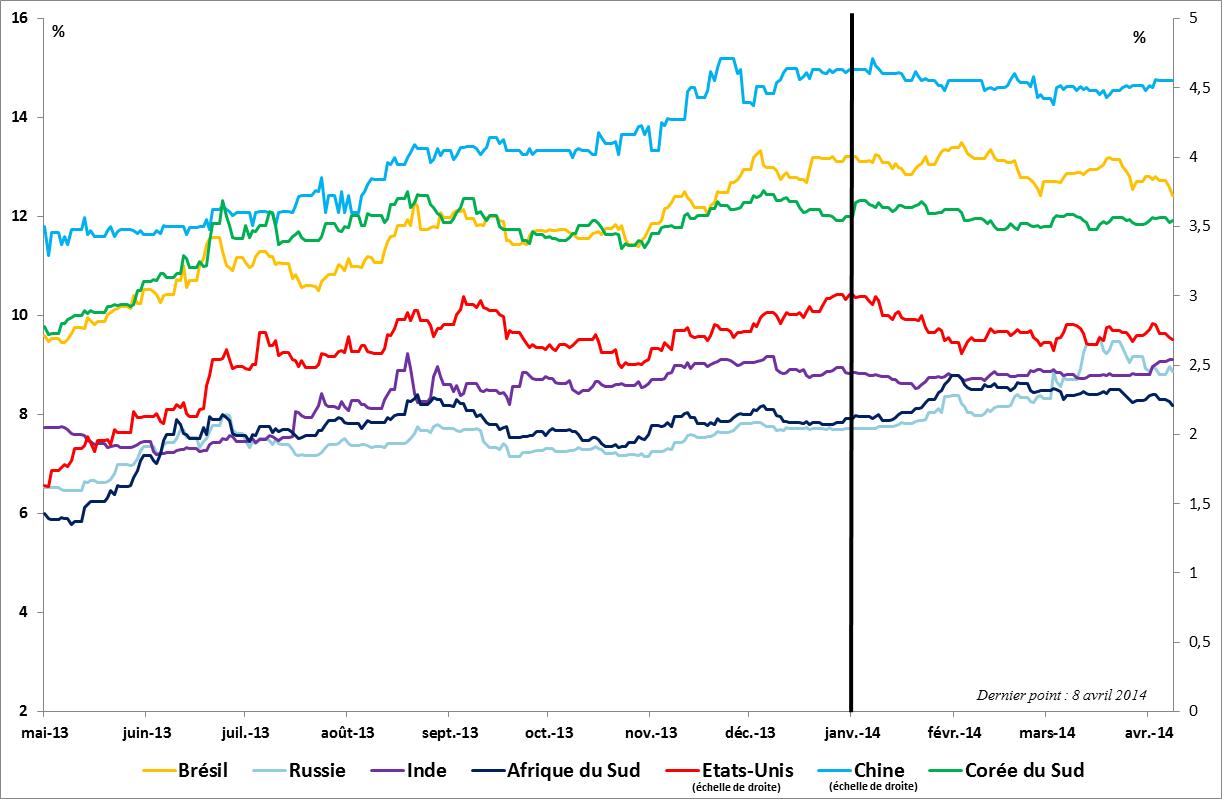

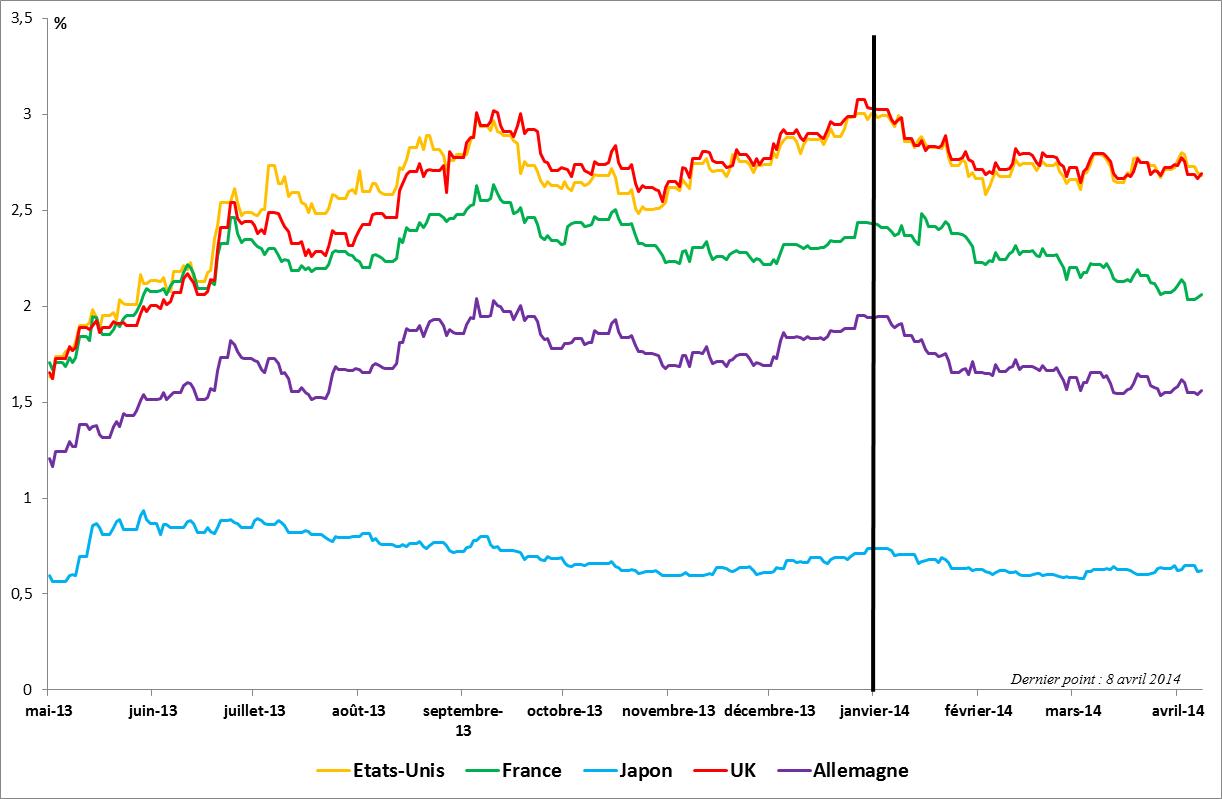

In the eurozone, this rise was also noticeable in the « core » countries ( +73 bps for German and French 10-year rates between May 1 and December 31) as well as in the peripheral countries (+20 bps for Italian rates, +32 bps for Spanish rates). However, for the latter, the relative improvement in economic conditions and the reduction in the risk perceived by investors helped to limit the rise in bond yields. UK rates, which have historically been strongly correlated with US rates, followed similar trends (+138 bps for 10-year rates between May 1 and December 31). This effect was also in line with the improvement in the UK economy and expectations of key rate hikes similar to those of the Fed.

Charts 2 and 3: Changes in sovereign bond yields in advanced economies (10-year maturity)

Sources: Macrobond, BSI Economics BSI Economics

Table 1: Correlations between monthly averages of sovereign bond yields and US yields (period: May 2013–January 2014; maturity: 10 years)

2. The transmission of this bond shock can be explained by both structural and cyclical factors.

a. Structural factors

Although a slow change is noticeable, the international monetary system (IMS) is still largely based on the preeminence of the US dollar. Securities denominated in dollars may therefore have an advantage over those denominated in other currencies.

As a result, US financial markets occupy a prominent place in the international financial architecture and often set the pace for movements in other markets. Certain US assets may benefit from a premium based on perceived lower risk when non-US markets are experiencing difficulties (flight to quality phenomenon), which can drive the market upwards. Conversely, when US stock markets are in trouble, they often drag other markets down with them.

In the bond markets, US rates serve as a benchmark, thanks in particular to the low risk premium demanded by investors and the high liquidity of US bonds. This is particularly true for short maturities and, in the primary markets, for longer maturities (1).

Thus, changes in bond yields in the US usually have international repercussions. However, other channels also play a role and, in the case of tapering, are of some importance.

b. Economic factors

The study of the international effects of tapering, and more broadly of all the factors related to the Fed’s quantitative easing, will obviously require in-depth work in the future, once we have more hindsight. However, the movements observed in the summer and detailed above have provoked criticism, particularly from emerging economies that felt at the mercy of the Fed’s decisions. Studies already highlight the extent of the impact of US monetary policy decisions on emerging economies (Neely, 2011).

There are various channels that can explain the variations observed:

– Portfolio rebalancing channel: In addition to overall rebalancing between different types of assets, long-term US bonds can be substitutes for long-term domestic bonds, and they are all the more substitutable because US Treasury bonds are denominated in dollars, highly liquid, and benefit from a low risk premium. Rising interest rates in the United States can therefore trigger an influx into these safe securities, whose yields become more attractive, to the detriment of local bonds, which see their rates rise. This mechanism will have an even greater impact if the country is dependent on external financing or is open to capital flows (2). This effect can be amplified by the sale of securities by investors holding US securities. Faced with losses or a need for liquidity (following changes in US securities), these investors may then close their positions on other assets in their own country or in third countries in order to honor their commitments, generate profits, or free up liquidity. Through the financial markets, this rebalancing may also affect different asset classes.

– Financial market channel: This is mainly the result of more specific channels, such as liquidity (inflows of liquidity into the markets following securities purchase programs, then withdrawals following tapering), risk-taking (search for yield in a low interest rate environment and disclosure of these risks when interest rates rise) and asset prices. The portfolio rebalancing mentioned in the previous point can therefore trigger significant movements across all asset classes.

– Banking channel: Banks’ losses on their bond portfolios following the fall in bond prices could be significant, particularly in Japan, where bonds are highly sensitive to interest rate fluctuations. Banks incurring losses could reduce their cross-border exposures. IMF staff (IMF, 2013) estimate that a 100 basis point increase in US long-term interest rates would result in aggregate losses on global bond portfolios estimated at 5.6% (higher than the losses incurred during previous episodes of interest rate increases), with bond prices moving in the opposite direction to interest rates. This decline in bond prices is likely to trigger losses on the balance sheets of institutions holding this type of asset (3).

These effects may be amplified by an overreaction of the markets, for example as a result of herd behavior during the transition to a less accommodative US monetary policy.

– Exchange rate channel: Securities purchase programs may have contributed to the depreciation of the currencies of the countries implementing them. They have effectively allowed an influx of liquidity and helped to keep domestic interest rates at historically low levels. The rise in US interest rates may thus, in a reverse movement, favor the appreciation of the dollar. The CAE (CAE, 2014) considers that the highly expansionary programs conducted by the Fed and the BoJ, compared with those conducted by the ECB, certainly contributed to the appreciation of the euro against the dollar and the yen observed in 2013. Thus, the end of QE3 is likely to cause the US dollar to appreciate against other currencies, particularly the euro, provided that the ECB’s monetary policy remains accommodative. This may temporarily boost activity in European countries, notably by improving terms of trade. However, this effect will be short-lived and will be offset by the negative shock of a rise in bond yields. In emerging economies, this could cause significant depreciation, justifying the more restrictive monetary policies (sometimes significant increases in key interest rates) implemented in the first quarter of 2014.

– Trade channel and external demand: Depending on the underlying reasons for the rise, changes in interest rates may cause variations in external demand from the United States to the rest of the world. If the rise in rates is the result of a positive surprise in activity, the impact on demand from the rest of the world may be positive. Conversely, if it is a stronger-than-expected reaction to monetary policy changes, the impact will likely be negative. Indeed, an upturn in US economic activity may translate into increased demand from the United States to the rest of the world, thereby boosting exports from its main trading partners. Conversely, an overly sharp bond shock could have strong recessionary effects, contributing to a deterioration in the US economy. With regard to the United States, the expected effects remain ambiguous and depend on the reasons that may have pushed rates up, as well as on exchange rate developments.

As highlighted in the April 2014 GFSR ( IMF, 2014), changes in the term premiums on sovereign bonds in different countries appear to be correlated with those in the term premium on US rates. However, the term premium on US bonds changed significantly during 2013 (BSI Economics, 2014). Thus, even though central banks are attempting to strengthen their control over the entire yield curve, particularly in developed economies through the use of forward guidance, the rise in the term premium is a factor whose trajectory is difficult to control.

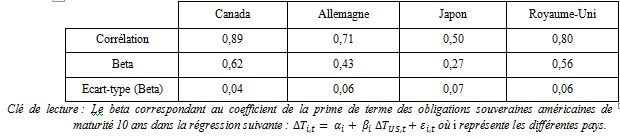

Table 2: Correlation and beta between the term premium on US sovereign rates and that of other advanced economies since May 2013 (maturity: 10 years; source: IMF)

Ultimately, the rise in long-term US interest rates in 2013 spread to other economies, both advanced and emerging, contributing to a tightening of financing conditions in these countries. This de facto tightening of monetary conditions is not necessarily appropriate to the economic situation of the countries concerned. In the eurozone in particular, the weak economic recovery in 2013 does not seem to justify the rise in rates observed in the core countries.

3. These bond market movements will have an impact on both emerging and advanced economies, the extent of which will depend on various factors.

a. In emerging economies

The effects on exchange rates and money markets in emerging economies have been particularly pronounced. While 2013 was marked by rising long-term rates, most of the monetary authorities in these countries raised their key rates in the first quarter of 2014 in order to support their currencies and remain attractive in a context of mistrust towards emerging economies.

In January, four central banks decided to raise their key interest rates. India raised its rates by 25 basis points, South Africa by 50 basis points, Brazil by 50 basis points and then again by 50 basis points in February, and finally Turkey by a more significant amount (up to 550 basis points for the main key interest rate).

More recently, following strong pressure on the ruble, the Russian Central Bank raised its base rate by 150 basis points to 7% and implemented a major securities buyback program to limit depreciation. Over the past twelve months, the cumulative increase has thus reached 550 bps in Turkey, 350 bps in Brazil, 175 bps in Indonesia, 150 bps in Russia, 75 bps in India, and 50 bps in South Africa. This tightening of monetary conditions does not necessarily appear to be in line with the recent slowdown in activity in these economies.

Furthermore, the development of local currency bond markets in emerging economies (see, for example, IMF, 2014) has reduced the asymmetry in foreign currency financing needs and increased the duration of debt. Local economic agents have thus been able to borrow in their own currency and participate in the boom in domestic bond assets, thereby promoting the development of certain characteristics of these securities (e.g., longer maturities). However, the share of foreign investors in these markets created a strong link between domestic bond rates and historically low rates in advanced economies (and thus indirectly eased domestic monetary conditions). Following the rise in rates, foreign investors were able to reduce their participation in emerging markets, which may have caused a rapid rise in domestic rates, a rise that could continue if the local investor base is not large enough to absorb all the shocks to capital flows.

In addition, since the financial crisis, assets held bymutual funds specializing in emerging market investments have increased significantly. These investors are more sensitive to short-term movements in financial markets than institutional investors, who are more concerned with the long term. The recent increase in market volatility has thus led to a reversal of capital flows out of emerging economies by mutual funds, which has been ongoing since May 2013, while institutional investors have maintained a stable participation. (4)

The development of a domestic base (for example, by promoting the development of domestic insurance companies or pension funds investing in local assets (5) ) could increase the capacity of emerging market economies to mitigate the volatility observed, which is due in part to the significant share held by foreign investors. (6)

b. In developed economies

Developed economies have also seen interest rates rise, particularly in the core economies of the eurozone and the United Kingdom. Faced with this tightening of financial conditions, which could jeopardize an already fragile and hesitant economic recovery, the role of the European Central Bank appears crucial. Indeed, the fragility of the improvement in economic conditions observed in the eurozone, as well as the notable lack of dynamism in the credit market in certain countries, underscore the need to maintain accommodative conditions and support economic activity. The role played by the ECB in this context appears to be essential, and the latter must remain vigilant to the possibility of a bond shock in the eurozone resulting from a rise in US rates.

Furthermore, with public debt remaining high in developed economies, an increase in interest rates would raise borrowing costs and could jeopardize the stability of public finances. This would be all the more dangerous given that most of these countries are undergoing consolidation and have limited room for maneuver.

Furthermore, financial stress could also hit developed markets. A recent analysis of BIS data suggests that banks’ exposures to the most vulnerable emerging markets are concentrated in the banking sectors of certain countries (the United Kingdom, the United States, and Spain) and in particular in the globally systemic institutions present there . The likelihood of a potential bond shock spreading from emerging economies to developed economies therefore appears very real (7).

Conclusion

Bond market developments therefore require increased vigilance in the short term, which will potentially require active policy on the part of the various monetary authorities. In particular, with inflation particularly low in the eurozone, the European Central Bank will need to be alert to the materialization of the bond risk highlighted here.

Nevertheless, in the long term, reforms remain necessary in both advanced and emerging economies to ensure the sustainability of public debt, avoid excessive exposure to interest rate fluctuations, and strengthen the resilience of financial markets. The apparent discrimination among emerging economies by financial markets during the stress of 2013, based in particular on the structural weaknesses of these economies, particularly highlights this point.

Finally, while the US Federal Reserve remains primarily concerned with economic developments in the US market, it has significantly stepped up its communication efforts in order to limit sudden adjustments and clarify market expectations. It is also aware that the US economy could suffer, through a second-round effect, particularly via the foreign trade channel, from a significant bond shock in the rest of the world, especially in the major emerging economies.

Notes:

(1) However, these interactions are not one-way, and European rates, particularly German rates, can in turn influence US rates.

(2) This effect may be all the more pronounced as the volatile share of capital flows has increased following the implementation of securities purchase programs by the Fed in the United States.

(3) Especially if they are recorded on the balance sheet at their market value.

(4) Data on capital flows from mutual funds specializing in investment in emerging economies have shown net capital outflows from these economies since June 2013. However, a more in-depth study by the Institute of International Finance, which includes flows from institutional investors investing directly in the domestic markets of emerging economies (rather than through other funds), highlights that emerging economies have received net inflows of USD 10 billion in equity portfolios and USD 71 billion in bond portfolios; instead of the net outflows of $36 billion and $37 billion initially calculated using EPFR data.

(5) These are long-term investors who are relatively stable and resilient to short-term fluctuations. However, their development entails certain risks in markets that are still immature. Furthermore, while this type of investor is less quick to respond to short-term disruptions, when they do leave a market, their departure is often more significant in terms of both scale and duration.

(6) See Adler et al., 2014

(7) According to BIS data, bank exposures involving Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Africa, Turkey, and Argentina are equivalent to USD 1,206 billion, of which USD 297 billion appears on the balance sheets of UK banks, USD 218 billion on the balance sheets of US banks and USD 204 billion on those of Spanish banks. The banks most exposed are believed to be Standard Chartered, HSBC, Santander and BBVA, although data on these exposures remain patchy and insufficiently accurate.

References:

– Adler, G., Djibgenou, M. L. and Sosa, S. (2014), Global Financial Shocks and Foreign Asset Repatriation: Do Local Investors Play a Stabilizing Role, IMF Working Paper

– BSI Economics, (2013), When the Fed sneezes, emerging countries catch a cold!, Moussavi, J.

– BSI Economics, (2014), Recent dynamics of US sovereign rates, Tenne , A.

– BSI Economics, (2014), Emerging Countries: What’s in Store for 2014?, Colin , C., Delepierre, S., Moussavi, J.

– CAE, (2014), The euro in the « currency war, « CAE, No. 11, January 2014, Bénassy-Quéré, A., Gourinchas, P.-O., Martin, Ph. and Plantin G.

– Chen, Q., Filardo, A., He, D. and Zhu, F. (2011), International Spillovers of Central Bank Balance Sheet Policies, Hong Kong Monetary Authority and BIS

– IMF, (2013), Global Financial Stability Report, October 2013, Chapter 1

– IMF, (2014), Global Financial Stability Report, April 2014

– Neely, C. J. (2011), The Large-Scale Asset Purchases Had Large International Effects, Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis, Working Paper 2010-018C