Abstract :

· The monetary policies of the ASEAN 6 have long had a single ultimate objective: to support an outward-looking development strategy [1];

· Based on international trade integration and capital attraction, monetary policies have long had two intermediate objectives: the pursuit of external stability and international industrial competitiveness;

· The appreciation of the yen in 1985 and the crisis of 1997 generated a dual reluctance to appreciate and to devalue the exchange rate sharply, which led to a search for « undervalued » stability;

· Prudent management and a favorable environment enabled these monetary authorities to achieve credibility, stability, and competitiveness until recently.

A holistic study of the monetary policies of the ASEAN 6 [2] may seem overly simplistic. The diversity of these countries means that any in-depth study must examine the specific characteristics of each one. Nevertheless, geographical and cultural proximity has led to a community of monetary policies based on similar and interconnected development strategies. This quest for external stability, which is relatively independent of major economic theories, responds to very real interests and a very concrete history.

I. Similar development strategies

Three countries serve as regional benchmarks for economic development: South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan. Through proactive policies, they have managed to catch up with the most advanced countries in less than half a century, starting from extremely low levels of development and without any particular raw material endowments.

In ASEAN 6, leaders wary of « Western liberalism » openly followed in the footsteps of these Asian success stories, whether it was Lee Kuan Yew (Singapore) in the 1960s and 1970s, or Mahatir (Malaysia), Soeharto (Indonesia), and Marcos (Philippines) with varying degrees of success in the 1980s and 1990s. This resulted in dirigiste policies, rather than statist ones, in which currency remained a political tool in the service of development. This strategy is based on low value-added manufacturing exports (textiles, assembly, simple electronic parts) and attracting foreign capital to compensate for the domestic savings deficit linked to a very dynamic demography and a lack of capital, while attracting know-how and technologies. The idea is that industries must be supported in order to contribute to the dissemination of know-how, in line with heterodox theories of infant industries and industrializing industries.

In this model, currency must be a source of stability to encourage investment while contributing to countries’ cost competitiveness through undervaluation, all in the service of industrialization leading to development. Sometimes initiated with a domestic focus (Malaysia, Indonesia), these strategies quickly shared a strong export orientation.

During the 1980s and up to the mid-1990s, a fragmented regional production apparatus developed in Southeast Asia, fueled by foreign capital and with industrialized countries as the predominant, sometimes indirect, end users. The gains associated with devaluation are reduced all the more when the share of imports in inputs is high (low degree of pass-through ). It was at this time that ASEAN, initially an anti-communist political association, adopted a commercial focus with the aim of creating a free trade area.

In countries with few savers (reduced political sensitivity to price variations), monetary policies were therefore subordinated to development objectives, with particular attention paid to exchange rate stability. This attention does not mean abandoning the objective of price stability, but the structural characteristics (significant share of raw materials in household expenditure, underdeveloped financial systems, high trade openness, and high risk premiums[4]) of developing countries weaken the link between domestic monetary policy and consumer price fluctuations, even though their openness strategy makes domestic prices sensitive to exchange rate fluctuations.

Due to low financial penetration, high consumer price sensitivity, and high risk premiums that hinder the transmission of monetary policy through credit and expectations channels, exchange rate stability has been the priority intermediate objective for economic development. In the 1990s and 2000s, only the Thai baht had a sustainable free float. The others used various forms of anchors, most often flexible and centered on the US dollar.

II. A double regional monetary trauma

In 1985, Japan yielded to US demands to revalue its currency, which appreciated by 50% against the US dollar (USD) in less than a year. The lesson learned by its Asian neighbors was the correlation between this appreciation and the « lost decade » that followed in the archipelago. A reluctance to appreciate spread throughout Asia.

Beyond a development strategy and a « fear » of appreciation, the ASEAN 6 countries share a particularly painful common experience: the 1997 crisis. The dual concerns of monetary stability and attracting foreign capital had made Asian countries the recipients of choice for investors, with a perceived low exchange rate risk and relatively unrestrictive legislation, all against a backdrop of impressive growth prospects.

In 1997, Thailand, which had a very significant need for external financing (current account deficit) and whose foreign exchange reserves were falling dangerously low, was forced to abandon its peg to the USD. The free float led to a depreciation of nearly 50% of the baht and a financial panic which, through contagion and expectations of further depreciation, wiped out the entire regional monetary stability based on more or less flexible pegs in less than six months. Apart from Singapore and Vietnam, the currencies of the region floated and fell freely. Excessive short-term and foreign currency debt in the private sector (particularly banking) transformed this monetary panic into a very serious economic crisis. It was not until the 2000s that these countries regained a level of effective per capita wealth equivalent to that of 1996.

This crisis, which is still very much in the minds of various leaders and monetary institutions in the region, is deeply linked to monetary policies and currencies, both in its causes and its consequences. Without going into the details of this « Asian miracle » bubble, there seems to be a consensus on its main causes. The stability of exchange rates at levels below their equilibrium levels generated an overabundance of foreign capital which, in addition to depleting the foreign exchange reserves of central banks, was not regulated by any legal or macroprudential framework.

This crisis, which is still very much present in these countries and within the monetary authorities themselves, did not lead to a review of monetary strategy, but added to a « fear » of appreciation and a form of reluctance in the face of rigidity and violent devaluations. In practice, this led to more flexible management of monetary policies.

III. Policies focused on exchange rate stability and reserve accumulation proved successful

Singapore was the country in the region least affected by the 1997 crisis. Its economic model as a small, ultra-extroverted country led it to successfully pursue a monetary policy officially based entirely on an exchange rate target, but with a number of unique features. The peg is to a basket of currencies that is subject to change. The basket and the pegging point are strictly confidential, although the pegging point appears to be close to a peg to the real effective exchange rate.

Such a policy, in addition to hindering the use of monetary policy to respond to domestic shocks and abandoning the objective of short-term smoothing of the economic cycle, requires credibility that comes from accumulating reserves (especially with external financing in the form of debt, as is often the case here) capable of offsetting actual and potential monetary flows with the outside world. This is more or less what the countries in the region have set out to do. This policy of accumulating reserves has the advantage of putting downward pressure on the exchange rate and thus contributing to the competitiveness of exports, which often come from firms that are unproductive by international standards.

Their extroverted strategies, their respective structural constraints, the double trauma of appreciation and rigidity, and the example of Singapore led the ASEAN 6 countries to pursue monetary policies aimed at stabilizing their effective exchange rates during the 2000s, with some success until recently.

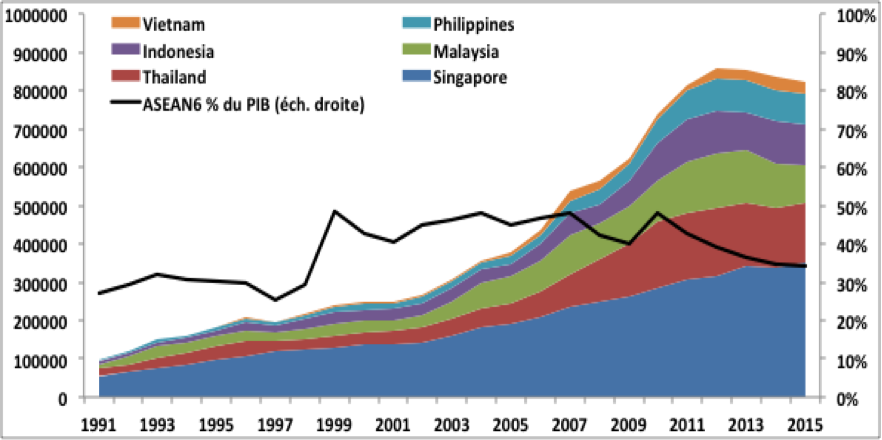

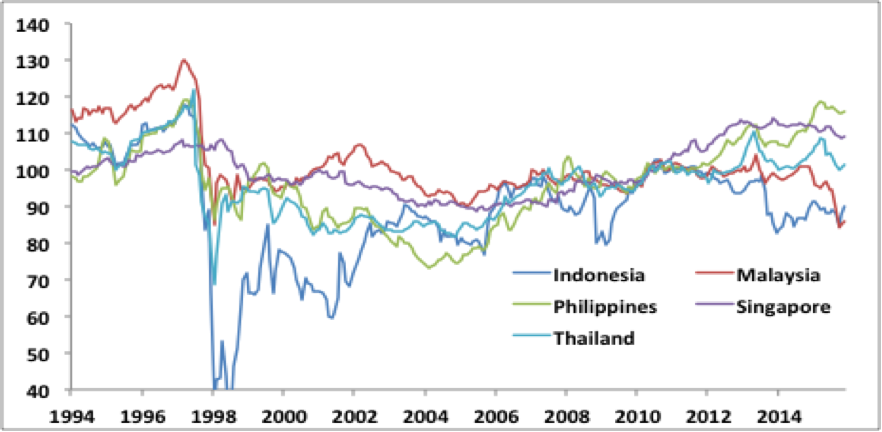

Stability of real effective exchange rates (base 2010=100) and accumulation of reserves (in USD)

Sources: National central banks, BIS, BSI Economics

For all countries, floating exchange rates, « administered » by monetary authorities quick to intervene, resulted in the accumulation of large foreign exchange reserves and currency undervaluation[6]. At the same time, capital movements were more tightly controlled, macroprudential supervision was strengthened, and monetary authorities were modernized (communications, data, objectives, tools, increased independence). Over the period 2000-2012, the observable results were impressive: reductions in domestic (inflation) and external (exchange rate) fluctuations in currency values, economic, financial, and industrial development, growth in the formal sector, and solid external accounts.

Conclusion

The reactions of the zone’s currencies to the first signs of normalization of the Fed’s policy (i.e., the end of the cheap USD) in the summer of 2013 served as a reminder that fragilities exist, foremost among which is their high sensitivity to international cycles. With the profound changes currently underway in the external monetary environment and internal structural developments, it is possible that the status quo of these ASEAN 6 monetary strategies, which survived the 2007 crisis, will be called into question, but we will look at that in a future article.

Bibliography:

How Asiaworks, J. Studwell (2013)

Les économies émergentes d’Asie, J-R. Chaponnière and M. Lautier (2014)

Exchange rate movements, firm-level exports and heterogeneity, A. Berthou, C-V Demian, E. Dhyne, Working Paper Series, ECB (2015)

Fear of Appreciation, E. Levy-Yeyati, F. Sturzengger, World Bank (2007)

Management of exchange rate regimes in emerging Asia; R. S. Rajan, Revenue of Development Finance (2012)

Exchange Rate Arrangements Entering the 21st Century; Reinhart, Rogoff (2004)

Understanding monetary policy in Malaysia and Thailand; R. N. Mc Cauley (2006)

Monetary policy approaches and implementation in Asia: the Philippines and Indonesia; R.S Mariano, D. P. Villanueva (2006)

Notes:

[1]A development strategy based on the country’s comparative advantages and its integration into the international division of labor, focused on exports and relying on foreign capital, as opposed to self-centered or global strategies.

[2]Only the ASEAN 6 countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines, Singapore, Vietnam) will be discussed, as they are larger in size and more integrated into the international monetary system.

[3]A strong state but with limited effective weight in the economy.

[4]The development of a financial market normally goes hand in hand with higher quality information and information processing, which strengthens the link between the policy rate and the effective interest rate.

[5]The variation in the real value of a currency relative to foreign currencies weighted by their respective values in the country’s trade

[6]Undervaluation is difficult to determine, but there is broad consensus on the period from 1997 to 2013