Summary:

– Production fundamentals in the rice market were not very good in 2007, but not radically different from previous years.

– Financialization was more significant than before due to the subprime crisis, but its impact remained limited because the rice futures market is narrow.

– Ultimately, it was the behavior of governments that caused the significant increase in rice prices observed at the time.

The financial and economic crisis often overshadows the fact that 2007-2008 saw one of the most dramatic food crises of recent decades in terms of its suddenness and its impact on the poorest populations. Following the increase in international rice prices, local prices rose by 38% in Bangladesh, more than 30% in the Philippines, and 18% in India [1]. Households in these countries spend 20 to 40% of their income on rice, and more than half of the world’s population needs this cereal to survive.

To explain this crisis, which has led to particularly violent food riots, the role of financial speculation is often highlighted. We saw in a previous article (financialization of agriculture, BSI Economics), that there has indeed been a significant increase in investment in agricultural index funds. Nevertheless, the evolution of rice prices is quite unusual and specific. This raises questions about the role played by another factor, or rather another actor, that has had a strong impact on prices in the rice market.

Agricultural balances before 2007

The starting point of the 2007-2008 food crisis is difficult to determine precisely, given how much agricultural balances have changed in recent years. Nevertheless, let us try to determine the context in which the crisis erupted. Firstly, agricultural food production depends, among other things, on the amount of land available. However, this land is in competition with two other uses: urbanization and non-food agricultural production. While we have been familiar with the former for several decades, the arrival of the latter has significantly changed the situation in terms of crop development. Indeed, a huge amount of land has been converted from food crops to crops for biofuel production. This phenomenon is particularly visible in the US where, for example, a 23% increase in corn cultivation for biofuel production has led to a 16% decrease in soybean cultivation. According to some economists, these uses have had a definite impact on the prices of all foodstuffs [2].

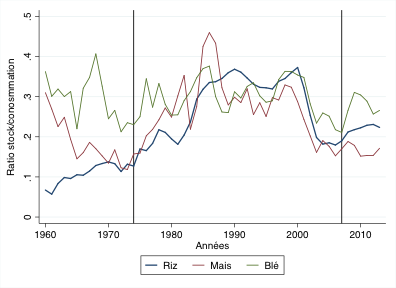

Secondly, the loss of cultivated land is accompanied by a decrease in stocks. In fact, in the first half of the 2000s, global rice stocks lost almost 50% of their volume. This considerably fuels tensions and causes an almost automatic increase in prices [4]. The graph in Figure 1 allows us to go further by noting that the decline in the ratio of stocks to consumption systematically decreases before the occurrence of a food crisis. For the three most widely consumed cereals in the world (rice, corn, and wheat), there is a significant correlation between the decline in stocks (before the mid-1970s and before 2007) and the onset of a crisis (symbolized by the vertical lines). It should be noted that the oil shocks were not the cause of the food price crisis of 1972-1973. It was caused by poor harvests due to climatic problems, low stock levels, as mentioned above, and an extremely tense political context between the USSR and the USA [5].

Figure 1: Evolution of stock-to-consumption ratios.

Sources: USDA data, BSI Economics

Thirdly, the reduction in cultivated land and the decline in stocks must themselves be viewed in the context of apparent food overproduction. Agricultural commodity prices continued to fall until the early 2000s, which significantly altered the global production balance: agriculture was no longer at the center of development policies, and some countries (especially in Africa) preferred to buy from abroad rather than produce at home, which was often more expensive. After 2000, input prices, particularly oil prices, contributed to the rise in cereal prices. This market reversal, also caused by a slight increase in international demand (mainly from emerging countries), was not a cause for concern at the time, as stocks were still high and production appeared to be increasing steadily.

Fourthly, we cannot deny the role of the financialization of agriculture, which began several decades ago and has increased significantly in recent years. The amounts invested in the main index funds (created in the 1990s) are estimated at around $13 billion in 2003 and $260 billion in 2008. However, between 2007 and 2008, these funds gained nearly $50 billion, or about one-fifth of their final value [6]. Finally, since the beginning of the 21st century, agricultural markets have been attracting investors who are not traditional market investors [7]. It is difficult to know whether this financialization has had a significant impact on international prices. Speculation logically affects the price of futures but not necessarily the spot price [8]. Several studies show causal links in both directions between futures prices and spot prices. Nevertheless, as with the decline in cultivated land, it cannot be completely denied that financialization has exacerbated tensions. Moreover, the most important aspect of the financialization of agriculture is its impact on strengthening the links between food prices. Indeed, several studies show that these prices (those of wheat, corn, and rice, for example) are linked beyond what can be explained by economic fundamentals. This would prove that finance, or rather speculation, plays a role in transmitting price variations [9].

Fifthly, we must also address the debate on the uncontrollable but nevertheless central element in agriculture: the climate. The context was extremely tense in 2005-2006 due to the factors mentioned above, but this was not the direct cause of the crisis. In fact, the 2006 grain harvests were extremely poor. The drought in Australia reduced its harvests by more than 50%, even though they had not reached the record levels of 2003. This reduced the supply of grain by more than 20 million tons. European grain production also experienced some difficulties, losing 11% of production, which reduced supply by more than 37 million tons. At the same time, Canada lost more than 4.5% of its production, which had remained stable in 2005 compared to 2004 levels. As for the US, losses amounted to more than 7.5% of its production, having already lost nearly 6% in 2005. Cumulatively, this represents a loss of more than 30 million tons in 2006 compared to 2005 for the US and Canada. The sum of these losses still represents 4% of 2005 production and does not take into account the fact that production was limited in Bangladesh (due to Cyclone Sidr and flooding: a loss of 2.5 million tons, or 10% of consumption [10]) and in China due to low temperatures.

Does this context explain the change in rice prices?

Following these episodes, and in this context of significant tension, the markets reacted to the prospect of a supply shortage. Prices rose above average and the inflationary machine was set in motion. Speculation must have played a role in the price increase, and this tended to intensify following the increase (the initial increase attracting new speculators). Depending on the variables and time frames considered, speculation has a definite impact on the international price of several agricultural commodities [11]. It is excessive in these markets, and even more so since the subprime crisis, which has led to a reallocation of investments.

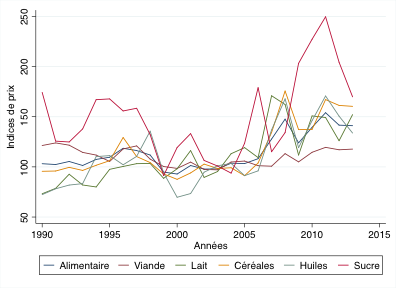

In addition, the correlations between international agricultural commodity prices mentioned above have only served to spread the price increase. As a result, the FAO indices for the main food commodities have risen significantly, as shown in the graph in Figure 2. On average, prices are almost 50% higher after the crisis and over a significant period of time, since the post-crisis period observed here covers nearly six years.

Figure 2: Price index trends.

Sources: FAOSTAT, BSI Economics

However, when we look at the evolution of rice prices compared to wheat or corn prices, we see that there is clearly something specific to this market that explains its evolution. The price per ton of rice rose relatively late compared to corn and wheat prices. Similarly, its increase during the crisis was greater and more sudden than that of the other two. The price of wheat doubled in ten months, the price of corn doubled in 20 to 24 months, but the price of rice tripled in just eight months (October 2007-April 2008; FAO (2010)), and even 2.5 times in 4 months (January 2008-April 2008).

Finally, it should be noted that wheat and corn prices have fallen back to their pre-crisis levels. However, this is not the case for rice: FAO price indices show that the price of rice was almost 100% higher until 2009 (in 2010 it was still 70% higher than before the crisis), while corn and wheat returned to levels 50% and slightly less than 50% higher, respectively, by the end of 2008. The price of wheat even fell to less than 25% above its pre-crisis level.

This particular development in the rice market is due to one player that is particularly active compared to other markets: the government.

The role of governments

We have just shown that agricultural markets, particularly grain markets, were very tense in the mid-2000s. However, while the prices of wheat and corn began to rise in 2006, the price of rice showed no signs of tension until 2007 and only exploded at the beginning of 2008.

The starting point for the meteoric rise in rice prices can be found in the link with other agricultural commodities, particularly wheat. When there is tension in one market, others are affected in turn via finance but also, and above all, via substitutability. When the price of wheat rises, rice consumption tends to increase. In fact, the governments of countries where food security (often precarious) is ensured by rice anticipated a rise in prices and reacted in an uncooperative manner, which led to the explosion in prices.

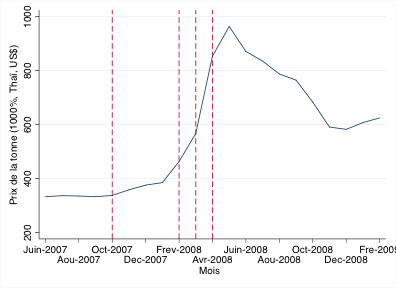

Figure 3: Highlighting four government decisions on the price per ton of rice

Sources: FAOSTAT, BSI Economics

To provide a complete understanding of the context, let us review the events chronologically (see [1] and [3]). On October 9, 2007, the Indian government, fearing that rising wheat and corn prices would impact the price of rice and consequently increase already high national inflation, decided to ban rice exports except for basmati rice (upcoming elections made it fear a rise in its unpopularity). From then on, the price per ton of rice began to rise (first red line in Figure 3).

Following India’s lead, Vietnam announced the same restriction. At around the same time, China decided to increase its export taxes, and the Philippine government announced that it was prepared to purchase large quantities, regardless of the seller and regardless of the price (second red line in Figure 3). On February 5, 2008, Vietnam reaffirmed its export ban, and the Philippines, by purchasing rice at $700 per ton, proved that its statements were not false. On March 17, Thailand began talking about export restrictions, which it ultimately did not implement, but the price per tonne nearly doubled in one month. On April 17, the Philippines purchased rice at $1,200 per tonne (third red line in Figure 3).

On April 30, it also proposed the creation of an organization of rice-exporting countries, which increased market players’ mistrust for fear of new export restrictions. This caused the price to rise again (fourth red line in Figure 3). The Philippines was forced to withdraw this announcement the following week. This was the first factor that triggered the price decline. After that, the harvest forecasts came in and announced very good results despite Cyclone Nargis in Myanmar and an earthquake in China in early May. Japan and the US agree to allow exports beyond the WTO agreements [12] and tensions ease. This comes against a backdrop of revelations of significant stock levels in China and Thailand. However, the price per ton remains significantly higher after the crisis than it was before.

In addition to the behavior of these major exporting countries (which alone account for 74% of global exports), there are restrictions, and even bans on exports for countries with lower production levels: Pakistan (9% of exports in 2011), Brazil (3.5% of exports in 2011) and Egypt (0.1% of exports in 2011). In April 2008, they respectively restricted, suspended and banned rice exports [13].

Conclusion

The conclusion we can draw from this crisis in the rice market is that, although the fundamentals were not very promising (declining stocks, slower production growth, financialization), they were not significantly different from those of other years. The crisis began with leaders’ concerns about price transmission between cereals (particularly between wheat and rice). Anticipating a price increase, they opted for measures that ultimately caused the increase.

However, the governments’ reaction was entirely rational, since rice is the most important cereal for food security in the vast majority of poor and developing countries. It should not be forgotten that the increase in the price of rice effectively pushes a significant portion of the population of these countries below the poverty line. This is unacceptable both for governments and for economic ethics. It is therefore necessary for the largest market players to agree on appropriate cooperative policies.

References:

[1] Slayton, T. and Timmer, C. P. (2008). Japan, China, and Thailand can solve the rice crisis—but US leadership is needed. Center for Global Development Notes. <http://www.cgdev.org/content/publications/detail/16028>. Accessed August 22, 2008.

[2] Mitchell, D. (2008). A note on rising food prices. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series, Vol.

[3] Dawe, D., Slayton, T. et al. (2010b). The world rice market crisis of 2007-2008. The rice crisis: markets, policies and food security, pages 15–28.

[4] Wright, B. and Bobenrieth, E. (2010). Special feature: The food price crisis of 2007/2008: Evidence and implications. FAO Food Outlook 59, 62.

[5] Falcon, W. P. and Timmer, C. P. (1974). War on hunger or new cold war? Stanford Magazine, Fall/Winter(64):4—-9.

Timmer, C. P., Dawe, D. et al. (2010a). Food crisis past, present (and future?): Will we ever learn? The rice crisis: Markets, policies and food security, pages 3–11.

[6] Masters, M. (2008). Testimony of Michael W. Masters before the U.S. Senate. http://www.hsgac.senate.gov//imo/media/doc/052008Masters.pdf?attempt=2.

[7] FAO (accessed January 27, 2014b). Read. http://www.fao.org/focus/f/SpeclPr/spro12-f.htm.

[8] The spot price is the international price. The futures price is the price of forward contracts for agricultural products. These two prices are different but related, although the characteristics of these links are difficult to identify.

[9] Pindyck, R. S. and Rotemberg, J. J. (1990). The excess co-movement of commodity prices. Economic Journal, 100:1173–89.

Pindyck, R. S. and Rotemberg, J. J. (1993). The comovement of stock prices. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(4):1073–1104.

Le Pen, Y. and Sévi, B. (2010). Revisiting the excess co-movements of commodity prices in a data-rich environment.

[10] Hossain, M., Deb, U., Dawe, D., et al. (2010). Volatility in rice prices and policy responses in Bangladesh. The rice crisis: markets, policies, and food security, pp. 91–108.

[11] Robles, M., Torero, M., & Von Braun, J. (2009). When speculation matters. International Food Policy Research Institute IFPRI Issue Brief 57.

[12] Slayton, T., Dawe, D. et al. (2010). The « diplomatic crop » or how the US provided critical leadership in ending the rice crisis. The rice crisis: markets, policies and food security, pages 313–341.

[13] Sekhar, C. (2008). World rice crisis: Issues and options. Economic and Political Weekly, pages 13–17.