Summary:

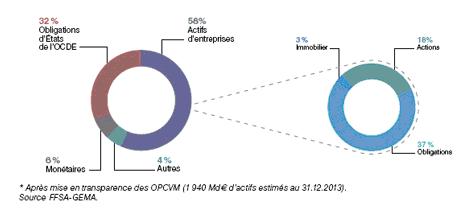

– French insurers’ investments amount to approximately €2 trillion.

– The Solvency II Directive will apply to European insurance companies from January1, 2016.

– Although it may seem significant at first glance, the penalty applied to equities under Solvency II is actually much lower.

– The impact of this reform on insurers’ asset allocation must be put into perspective in light of the macroeconomic context, financial markets, and household behavior.

The insurance sector is a major player in the French economy. In addition to employing approximately 150,000 people, French insurance companies have around €2 trillion in investments, which is almost equal to France’s GDP. More than half of these investments (see chart below) are made in companies. Furthermore, like the Caisse des Dépôts et des Consignations, insurers are generally considered to be long-term institutional investors, thereby promoting the country’s economic development.

Currently, insurance companies are subject to the Solvency I prudential framework. This system, established in the 1970s, regulates insurers’ investments and determines the solvency margin solely on the basis of premiums collected and benefits paid. The minimum capital requirement is therefore not sufficiently adapted to the risks actually incurred by the companies (market risk, counterparty risk, catastrophe risk, etc.). To address these shortcomings, the Solvency II Directive, which was passed by the European Parliament in 2009 after many twists and turns, is due to come into force on January1, 2016. The main objective is, of course, to provide greater protection for policyholders and the European Union’s financial system.

1- The Solvency II Directive

Under this new prudential regime, the assessment of an insurance company’s overall solvency has become more complex and sophisticated, with an economic perspective. All the risks inherent in this sector of activity must be taken into account and quantified fairly accurately at their fair value. Thus, unlike Solvency I, the risks associated with taking out a home insurance policy, for example, will not be considered identical to those associated with a car insurance policy.

Solvency II is divided into three main pillars:

– Pillar 1 deals with quantitative requirements, i.e., the calculation of economic capital, the SCR (Solvency Capital Requirement), and therefore the solvency ratio.

– Pillar 2 addresses qualitative requirements related to governance, risk management, the ORSA process, etc.

– Pillar 3 aims to improve communication and information sharing with supervisory authorities and the public.

To be considered solvent under Solvency II, all insurance companies must have a capital requirement (known as SCR) that is lower than their economic capital. This target capital amount is determined in such a way as to ensure that each insurance company can meet its commitments in 99.5% of cases over a one-year horizon.

The calculation of the SCR, based on a risk-based capital (RBC) approach inspired by the American model, follows a modular architecture:

Source: EIOPA (matrix of modules and sub-modules), BSI Economics

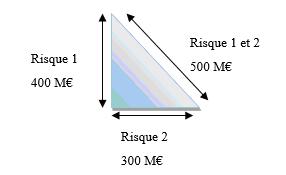

For each sub-module and when using the standard formula, the capital requirement is calculated using a scenario predetermined at the European level. These different requirements are then aggregated using correlation matrices according to two levels of aggregation between sub-modules and between modules. Thus, the SCR is not simply a sum of penalties. In fact, the various risks borne by an insurance company are not necessarily related and may occur at different times. For example, a sharp fall in the stock markets does not necessarily imply storms/floods causing heavy financial losses for insurers. The probability of these two extreme events occurring in the same period is very limited and much lower than the sum of the two respective probabilities of occurrence. For example, 2010 was marked by stagnation in the CAC 40 and a major natural disaster: Storm Xynthia (costing insurers around €1.5 billion). If two risks are independent of each other, the expected capital amount is calculated using Pythagoras’ theorem:

In the example above, the total amount obtained by aggregating two independent risks valued at €400 million and €300 million respectively would be €500 million (approximately 29% less than the sum of the two risks, which is €700 million).

As this article focuses on the impact of Solvency II on the financing of the economy, only the Market SCR (corresponding to the capital required to cope with fluctuations in the market value of the insurer’s investments) will be detailed. However, this amount should be put into perspective, as it must be aggregated and diversified with other risks specific to insurance (i.e., related to the insurer’s liabilities).

For example, for a non-life insurer, the Market SCR generally represents a small portion of the overall SCR. By way of illustration, consider that the SCR of a non-life insurance organization breaks down as follows:

The « net » capital requirement related to this insurer’s market risk is equal to the change in SCR caused by the disappearance of the risk of loss on investments and therefore of the Market SCR.

Source: BSI Economics

It appears that the Market SCR, individually valued at €150 million, ultimately represents approximately €72 million in the overall SCR, or slightly less than half of its initial value! The effects of a particular penalty on the overall SCR and therefore on the solvency ratio are therefore not easily identifiable at first glance.

The Market SCR is broken down into several risk sub-modules (interest rates, equities, real estate, spread, foreign exchange, and concentration) as shown below:

In the context of equity risk, the penalty applied to the market value of « type 1 » equities in the portfolio (directly or via funds), i.e., those listed in the OECD, is 39%. Depending on the stock market cycle, the various shocks may vary by plus or minus 10 points and are therefore between 29% and 49%. Indeed, if the market is at the « top of the cycle, » the probability of a decline is likely to be higher, and conversely when the market is at the « bottom of the cycle. »

Shares that are not « type 1 » are referred to as « type 2 » and are penalized at a rate of 49%, also with a symmetrical adjustment. However, venture capital and alternative investment funds, which are the instruments that finance the real economy the most, may be penalized at 39% (rather than 49%), which limits the impact on the solvency of the insurer holding such investments.

Under certain conditions and with the regulator’s approval, it is also possible to apply a reduced penalty of 22% for equities.

In order to smooth the impact of Solvency II over several years, a transitional measure provides for the stock of shares in the portfolio as of December 31, 2015, to be gradually charged from 22% to 39/49% over seven years. Furthermore, given the many twists and turns we have seen since 2009 and the vote on the Solvency II Directive, it seems likely that negotiations will still lead to a change in these penalties.

The SCR Change consists of penalizing investments held outside the euro zone by 25%. Thus, we can legitimately expect a concentration of insurers’ investments in the euro zone. An increase or, at the very least, stagnation in investments in France is therefore highly predictable.

Within the SCR Actions itself, there is a diversification phenomenon between « type 1 » and « type 2 » shares. In addition, the various market risks (interest rates, equities, spreads, real estate, foreign exchange, and concentration) are also diversified in the SCR Marché, resulting in a significant reduction in « gross » penalties on equities. Ultimately, although at first glance a « gross » shock of 39% is applied to equities (listed in the OECD), we have just seen that in reality the net penalty may be much lower: in the fictitious example presented above, it amounts to only 20%, representing a reduction in the shock of around 50%!

In addition, in order to respond to issues related to new prudential requirements, insurance asset managers are creating complex funds to maximize the return/capital cost ratio. The use of hedging tools (put options, CDS, swaps, etc.) makes it possible to limit the impact of a potential decline in the market value of certain assets (equities, bonds, fixed-income products, etc.).. For example, purchasing a credit default swap (CDS) on the financial markets allows insurers to hedge against the financial consequences of a decline in the value of the underlying asset (bond) following a deterioration in the credit quality of the issuer, thereby reducing the penalty on the bonds covered. Similarly, an insurer can also protect itself against the risk of a fall in share prices by using put options. For each share held, a put option on the same underlying asset can be purchased, thereby limiting the overall risk of loss. In fact, if the market value of the stock falls, the price of the put option will rise, thereby reducing the depreciation of the portfolio (stock, option). This mechanism has the advantage of taking advantage of market upturns while limiting losses in the event of an extreme bearish scenario. According to some professionals, this type of financial arrangement could reduce the equity penalty (type 1) to 25%, which is equivalent to the penalty applied to a BBB bond with a maturity of 10-15 years.

Finally, investing in equities, which are usually more profitable than other investments, generates higher financial returns over the long term, which can be incorporated into equity capital, thereby strengthening the organization’s future solvency.

2- The historical behavior of insurers with regard to this new prudential regime

At the end of 2012, life insurers’ investments accounted for around 90% of total insurer investments (life and non-life). The behavior of insurance companies is therefore highly dependent on that of… households! If, for example, households redeem their unit-linked life insurance policies en masse (which in 2012 consisted on average of 28.6% equities compared with 7.7% for euro-denominated funds), insurers will automatically have to sell the corresponding investments, a significant portion of which is invested in equities, to these policies, resulting in an inevitable decline in insurers’ investments in equities.

Furthermore, like any investor, insurers implement asset allocation strategies and seek optimal performance without neglecting the impact on assets and liabilities. Thus, in the event of a stock market crisis, they will try to limit their losses by, for example, selling shares. Their behavior, like that of savers, is therefore strongly influenced by the macroeconomic environment.

The impact of Solvency II on insurers is not uniform, as it varies greatly depending on size, legal status (mutual, provident institution, insurance company), sector of activity (the share of investments in equities was 10.4% for life insurers compared with 27.7% at the end of 2012), levels of equity capital, strategy, and the risk appetite of insurance company managers. In order to assess the consequences of this directive on the French economy, it therefore appears necessary to analyze its impact on the insurance market in general rather than on specific insurance companies.

The figures presented in the graph below are taken from various studies by the FFSA and GEMA. They show the evolution of the share of investments allocated by French insurers to corporate financing. They are compared with the changes in penalties applied to shares in the preparatory exercises for Solvency II.

Source: BSI Economics

Changes in the equity shock during preparations for the implementation of the Solvency II Directive:

*: the equity penalties applied in the preparatory exercises as at December 31, 2010 and December 31, 2012 are 39%, taking into account a dampening effect.

Transitional measures aimed at gradually increasing the equity shock from 22% (penalty applied in 2016) to 39% (penalty applied from 2023) were added in 2012 and are still in place.

Historically, the proportion of equities in insurers’ investments has been mainly a function of the macroeconomic environment (periods of euphoria or financial crisis) rather than prudential considerations. The impact of changes in the penalties applied to equities under the Solvency II prudential reform appears to be relatively limited from a macroeconomic perspective. Indeed, the introduction of a 40% penalty on equities did not lead to divestment. The sharp decline (of around 25%) in the share of equities between 2007 and 2008 can largely be explained by the financial crisis, as equity shocks remained constant between these two years.

Furthermore, between 2005 and 2013, insurers strengthened their role as financiers of the economy. Despite the introduction of Solvency II, the share of investments allocated to corporate financing (equities and bonds) grew in a broadly linear fashion (excluding periods of bubbles and financial crisis), rising from 49% in 2005 to 55% in 2013.

In recent years, insurers have distinguished themselves by refocusing their investments on France, which appears to be beneficial for the financing of the national economy. At the end of 2012, 45.4% of insurers’ total investments were in securities issued by residents, compared with 35.9% in 2008. The main beneficiaries of this concentration of investments are financial institutions and, to a lesser extent, the government and other public administrations. The share allocated to non-financial companies declined slightly during this period. Nevertheless, by investing in financial companies, insurers have likely contributed indirectly to the financing of non-financial companies.

The purchase by insurers and holding of highly liquid shares in international companies such as those comprising the CAC 40 are likely to have limited benefits for the financing of the French economy. Indeed, these globalized companies have a worldwide reputation and teams specializing in investor relations, which, combined with highly internationalized finance, facilitates their financing. For example, according to a study by Alphavalue, the share of foreign investors in the CAC 40 rose from 41% in 2007 to just over 50% in 2014 without causing any significant financing difficulties for companies in the Paris flagship index.

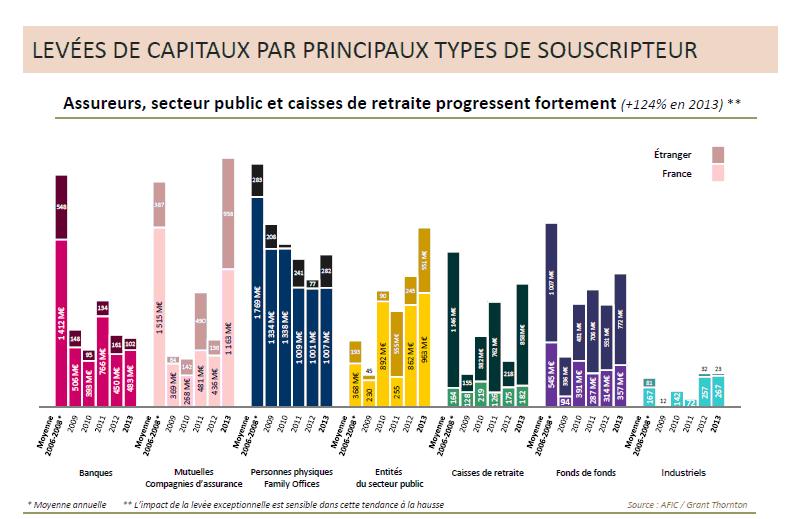

The role of insurers in financing smaller companies appears to be much more important and vital for the French economy, particularly in the context of venture capital, development capital, and turnaround capital transactions. In the private equity sector, as shown in the chart below, after four very sluggish years following the 2008 financial crisis, a sharp increase in investment by mutual insurance companies and insurance companies was observed in 2013. This increase can be explained in part by an exceptional fundraising effort last year. However, this seemingly cyclical trend could continue, as a major French insurer, for example, has declared its willingness to invest around €4.8 billion in private equity between 2014 and 2018. Similarly, many insurers have recently announced their intention to increase their investments in this asset class. Finally, as reported by Argus de l’Assurance, « at the end of 2013, French insurers had invested €46.6 billion in SMEs (€37.2 billion in capital, €6.4 billion in debt and €3 billion via BPI France), compared with €22 billion at the end of 2009, » proof of insurers’ current interest in small businesses.

Sources: BSI Economics, « Private equity activity in 2013, » AFIC and Grant

In order to diversify their portfolios and increase returns, insurers are increasingly interested in « alternative investments. » For example, a major global insurer has invested more than €2 billion in renewable energies, particularly in France. Insurers are also increasingly attracted to infrastructure financing, which is partially uncorrelated with financial markets and promotes economic growth. According to Standard and Poor’s, listed infrastructure project bonds offer an attractive yield of 4% to 5% (compared to less than 3% for sovereign bonds with the same rating). These projects also appear to be relatively safe, as according to the same rating agency, the default rate on this type of investment is significantly lower than that of corporate bonds. The recovery rate is also high (around 75%).

In addition, following the 2013 life insurance reform, the creation of « vie-génération » contracts should substantially increase insurers’ investments in SMEs and mid-cap companies. In fact, provided that at least one-third of the funds are invested in such companies (or in social housing or social and solidarity economy enterprises), additional tax benefits are granted to the beneficiary in the event of the insured’s death.

In addition, the new « euro-growth » life insurance contracts, which aim to encourage savers to participate in the financing of companies, promise an average return higher than euro-denominated funds with a capital guarantee after eight years of ownership. Thus, if the French take up this new type of life insurance, which is halfway between euro-denominated contracts and unit-linked contracts, insurers should automatically increase their investments in equities or loans/bonds for companies with expected returns higher than sovereign bonds.

The success of these new contracts should be facilitated by a significant drop in the rates offered by euro funds. Indeed, Christian Noyer, Governor of the Banque de France, recently declared himself in favor of a significant reduction in the rates of return on life insurance contracts (euro funds). Given the current low interest rate environment and the significant inflows into life insurance in recent times, insurers are buying bonds at very low rates with relatively long maturities. Thus, in the event of a rapid rise in interest rates, the returns offered by life insurers’ euro funds would be uncompetitive, likely leading to massive redemptions by savers. Life insurers would then be forced to sell bonds at unrealized losses, generating heavy losses that could threaten their solvency. To avoid such a disaster scenario, it is therefore essential for them to increase the profitability of their investments by turning, for example, to assets with better returns such as equities or corporate bonds, which finance the economy more than sovereign bonds.

As a result, Solvency II appears to be a factor influencing insurers’ asset allocation, but its impact must be put into perspective in light of the many other significant challenges and regulatory changes that these organizations are also facing.

The main issue raised by the entry into force of this Directive does not concern the financing of the economy, but rather the pro-cyclical nature of insurers resulting from this reform. Indeed, the market value valuation of assets (insurers’ assets and liabilities are much longer-term) adopted by this new regulation will likely force insurers to sell their investments in the event of a financial crisis, leading to a more pronounced decline in financial markets, triggering further asset sales, and so on. However, insurers’ behavior has historically been considered countercyclical (i.e., they would buy heavily depreciated assets during crises at the bottom of the cycle or avoid selling their investments at unrealized losses), thereby cushioning financial crises. This dual effect (the loss of countercyclical behavior in favor of procyclical behavior) appears to be a worrying factor that could substantially aggravate future financial crises. In addition, these new methodologies will lead to high volatility in the economic capital of insurance companies and therefore in their solvency ratios, thereby exacerbating systemic risk.

Conclusion

The impact of the Solvency II Directive on the financing of the French economy appears to be relatively limited. Although the capital requirements for equity investments appear significant at first glance, they are in fact much lowerin reality . The modular structure of the SCR calculation has the advantage of generating significant diversification gains. In addition, there are financial techniques that reduce the penalties applied to equities, for example through the purchase of put options. Furthermore, Solvency II is being implemented gradually, with a transitional measure applying to equities in particular, aimed at smoothing the impact of this Directive on insurers’ solvency. Finally, the shocks used in the standard formula should not be considered set in stone. Indeed, negotiations and adjustments on certain problematic points of the reform are entirely possible in the coming years (for example, in order to limit distortions of competition between pension funds subject to the IORP Directive and insurance organizations falling within the scope of Solvency II).

Finally, it appears very difficult to establish empirically a direct link between Solvency II and divestment in equities. The behavior of insurers in terms of asset allocation is in fact the result of various factors and is not solely guided by the Directive. For example, the evolution of insurers’ asset management policies since the early days of Solvency II is likely to be explained more by the macroeconomic environment, market conditions, and household behavior (life insurance) than by prudential requirements. In addition, at present, alongside these various factors, there are many other significant phenomena at play, such as the decline in sovereign bond yields, changes in national legislation, market initiatives aimed at developing financing for SMEs/mid-cap companies, and the specific strategies of each organization. For example, recent life insurance reforms are likely to encourage households to invest in products (euro growth, life generation) that finance the economy more than euro funds. This will automatically lead to an increase in insurers’ investments in companies.

Bibliography:

Numerous press articles published by L’Argus de l’Assurance

FFSA annual reports

Various publications by the Banque de France and the ACPR

EIOPA

« Private equity activity in 2013, » AFIC

« The consequences of Solvency II on corporate financing, » Anne Guillaumat de Blignieres and Jean-Pierre Milanesi (February 2014), Les éditions des JOURNAUX OFFICIELS