Abstract:

– Since the late 1990s, private education has grown significantly in many developing countries.

– This growth in private schools, particularly low-cost ones, can be explained by deficiencies in both the quantity and quality of public schools.

–While in some respects the rise of private education helps to compensate for certain shortcomings in the public sector, it is also a significant factor in socio-economic inequality.

– It is therefore essential that public policies seek to leverage the complementarity between the private and public sectors in order to ensure quality Education for All.

Improving access to education and the quality of teaching has become one of the key objectives in developing countries (see the article The challenge of access and quality of education in developing countries). This imperative has been recognized at the international level (Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948; World Conference on Education for All, 1990; Millennium Development Goals, 2000) and all countries have committed to taking measures to give every individual, regardless of social background, the opportunity to attend school.

This has resulted in a wide range of measures affecting both supply (construction of new schools, distribution of textbooks, etc.) and demand (awareness campaigns, conditional transfers, etc.). Unfortunately, despite some significant progress, the expected results have not yet been achieved. In low- and middle-income countries, 55 million children of primary school age were not enrolled in school in 2012. Faced with these failures and persistent educational inequalities, some politicians and economists see private education as an opportunity to compensate for the shortcomings of the current school systems that characterize many developing countries today. Can the expansion of private education improve access to education, or does it only exacerbate inequalities?

In this article, we look at the growth of the private education sector in developing countries and explain why private schools are attracting more and more parents. We then examine the extent to which this expansion helps to optimize education systems or, on the contrary, contributes to the persistence of inequalities in education and the labor market.

Definition and overview of the private sector

A broad definition considers any formal school that is not part of the government education system to be a private school. This is the definition used by UNESCO. However, the boundaries between private and public education are often blurred. First, public schools sometimes charge high tuition fees (Kitaev, 1999; Lewis and Patrinos, 2012). In addition, in many countries, private schools receive public funding to cover their operating costs (Kitaev, 1999; Lewis and Patrinos, 2012). Finally, the state may also exercise some control over these institutions by imposing strict rules on curriculum, accreditation, or teacher qualifications (Rose, 2006).

Not only is it difficult to clearly differentiate between private and public schools, but private schools are also very diverse and form a particularly heterogeneous group. They do not have the same objectives. Some operate as businesses seeking to maximize their profits, while others are non-profit non-governmental institutions or religious schools.

The educational landscape has changed significantly in recent decades in many developing countries. However, it is difficult to accurately assess their importance due to the difficulties in defining the concept of private education. [1]Nevertheless, there is general agreement that since the late 1990s, the number of private schools, particularly those with low tuition fees, has grown impressively (Kitaev, 1999; Kingdon, 1996; Latham, 2002; Tooley and Dixon, 2003). The increase in the number of schools has been accompanied by an increase in private school enrollment, suggesting that these schools are meeting a certain demand. Figure 1 shows, for example, that in low-income countries, 16% of children enrolled in primary school are enrolled in a private school, compared to 9% in 1975. This increase has been particularly marked in upper-middle-income and low-income countries.

Figure 1: Change in the percentage of primary school students enrolled in private schools

Source: Author using UNESCO statistics and World Bank classification, BSI Economics

In some developing countries, the share of private education has reached record highs. In Mali, for example, 35% of pupils enrolled in primary school have chosen a private institution, compared with only 6% in 1973.

Understanding the reasons for the expansion of the private education sector

Several explanations have been put forward to explain the rise of these private schools. The first two explanations relate to insufficient public provision, while the last two are due to these schools being ill-suited to demand. First, it is possible that they were established in remote areas where there were no public schools. They therefore attract a new population and their development can have beneficial effects on overall school enrollment. Children who were not enrolled in school due to a lack of nearby schools are now enrolled. This is often the case with schools run by NGOs.

Second, in many developing regions, the number of public schools is insufficient to meet the demand for schooling (Colclough, 1997). Due to budgetary constraints and limited public funding, some governments are unable to increase the supply of schools. Private schools then compensate for this shortfall. Nishimura and Yamano (2013) showed that in Kenya, parents chose to enroll their children in private schools because public school classrooms were overcrowded.

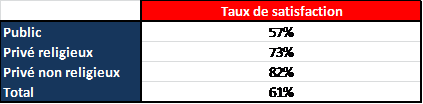

The third main reason put forward is the inefficiency of public systems in terms of quality. Academic performance and the quality of education provided in government schools are relatively low compared to those in private schools. Parents, disappointed by the quality of public institutions, would then choose to enroll their children in private schools in the hope that they would leave the school system with more skills and knowledge (Andrabi et al., 2002; Aslam, 2009; Heyneman and Stern, 2013; Rose, 2006). Glick and Sahn (2006) showed that, in the case of Madagascar, parents tended to choose the private option when the services available in public schools were of poor quality. A recent World Bank study (Tsimpo and Wodon, 2013), using data from household surveys, clearly shows that in six sub-Saharan African countries, parents are on average more satisfied with private schools than with public schools (Table 1).

Table 1: Average parental satisfaction rates with public and private primary schools in six sub-Saharan African countries

Source: Tsimpo and Wodon, 2013

Note: Average for seven sub-Saharan African countries obtained using household surveys: Burkina Faso (2007), Burundi (2006), Ghana (2003), Senegal (2005), Republic of Congo (2005), Niger (2007), and Mali (2006).

Finally, the last reason, which is somewhat related to the previous one, may be due to differences in the curricula between the two types of institutions. Parents who place greater value on religion, for example, may choose to send their children to a madrasa (Koranic school) or a Christian school. Differences in the language of instruction may also explain why parents prefer private schools.

While it is undeniable that in many countries, in Asia as well as in Africa, private education is playing an increasingly important role in the delivery of knowledge, there is debate about the effects of this development.

Impacts and challenges of private education

Proponents of private education argue that, given limited government resources, the public school system alone would be unable to achieve the goal of Education for All (World Bank, 2002). Furthermore, the quality of education provided in public institutions has declined and is often well below the quality of education in private schools (Aslam, 2009; French and Kingdon, 2010; Kingdon, 2008, Tooley and Dixon, 2007) [2]. These differences in performance are thought to be due in particular to teachers who are more present (Kingdon and Banerji, 2009; Andrabi et al. (2008); Tooley et al., 2011) and use more effective teaching methods in private institutions (Kremer and Muralidharan, 2008; Muralidharan and Sundararaman, 2013; Kingdon and Banerji, 2009; Singh and Sarkar, 2012). The literature on this issue explains this by the fact that, in private schools, teachers are accountable to their employers and have more incentive to perform well (Aslam and Kingdon, 2011; Kremer and Muralidharan, 2008). Private schools, especially those with low tuition fees, could therefore cater to more children and provide them with a better quality education (Tooley and Dixon, 2003). Finally, with the emergence of private schools, competition in the education sector increases, which would have a positive effect on the quality of public schools, as the latter must raise their standards if they want to continue to attract a certain level of demand (Friedman, 1955; Holmes et al., 2003).

However, some have expressed doubts about the effectiveness and fairness of these policies aimed at privatizing education. Access to education is a universal right, and placing it in the hands of private actors could have adverse effects. In India, for example, private schools tend to be located in the wealthiest areas and remain out of reach for the most disadvantaged students (Pal, 2010). If private schools do not become more democratic and only attract certain specific segments of the population, this would have significant consequences in terms of inequality. Students from the poorest and least educated households would remain in public schools and be condemned to less prestigious jobs.

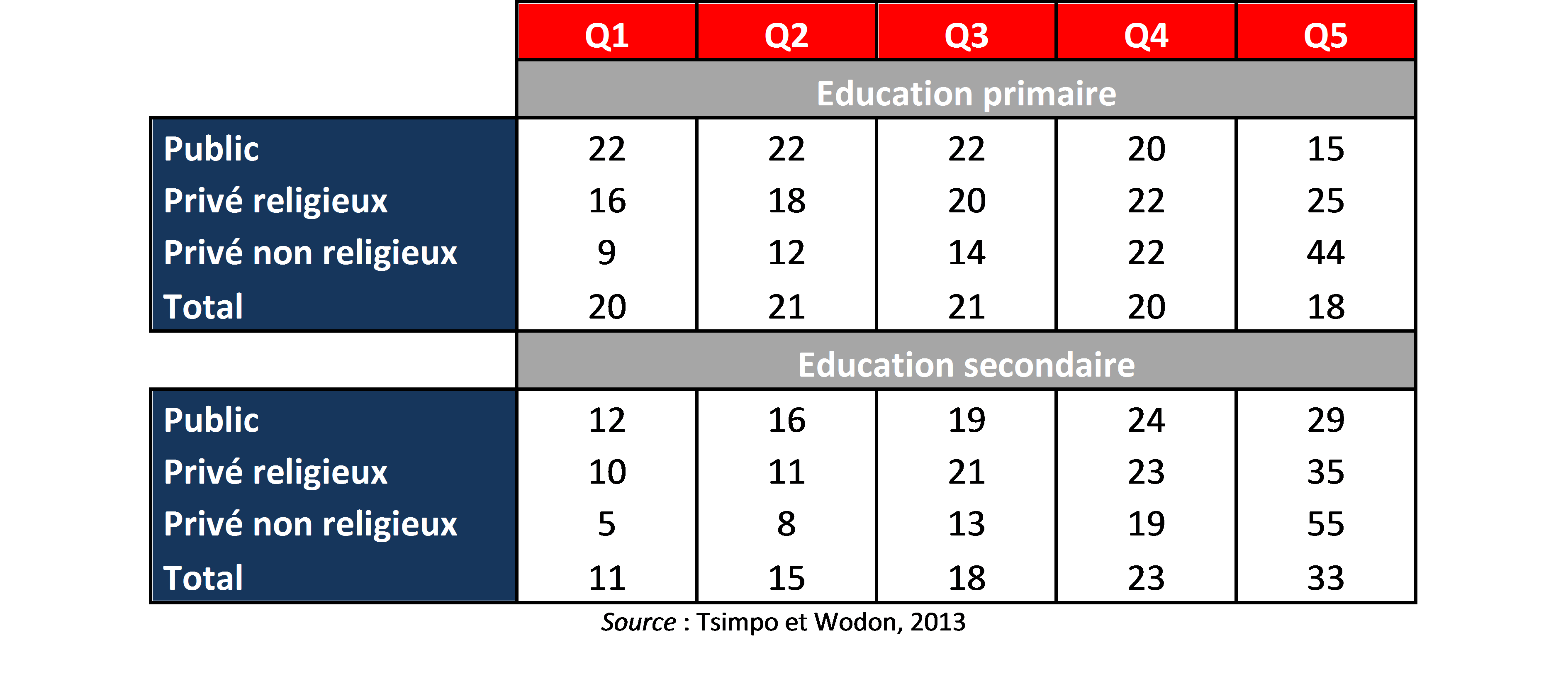

Private education could then become a vehicle for social reproduction and would perpetuate inequalities at school and later in the labor market. A recent World Bank study (Tsimpo and Wodon, 2013) estimates whether private schools are able to attract students from disadvantaged backgrounds in sub-Saharan Africa (Table 2). In the 16 countries studied, the majority of students enrolled in private schools come from the wealthiest households. At the primary level, 21.7% of public school students belong to the lowest wealth quintile, compared with only 8.5% of students in the secular private sector.

Table 2: Distribution of students in Sub-Saharan Africa by wealth quintile and type of institution

Note: Average for 16 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa obtained using household surveys: Burkina Faso (2007), Burundi (2006), Cameroon (2007), Democratic Republic of Congo (2005); Ghana (2003 and 2005-06), Senegal (2005), Sierra Leone (2003/04), Swaziland (2009/10), Kenya (2005), Zambia (2004), Malawi (2004), Republic of Congo (2005), Nigeria (2003-04), Niger (2007), Mali (2006), and Uganda (2010)

However, there are differences between countries (Table 3). The distribution appears to be more equal in Sierra Leone than in Burkina Faso, where only children from the most privileged backgrounds are enrolled in private schools.

Table 3: Distribution of students enrolled in non-religious private primary schools by household wealth quintile (%)

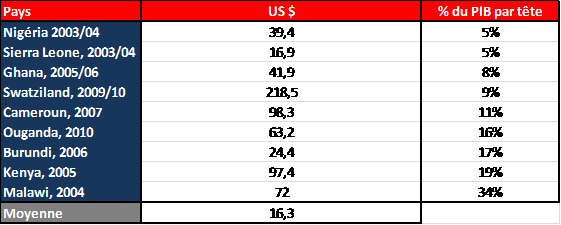

These differences can be explained by the differences in private school costs between countries (Table 4). For example, in Sierra Leone, private school fees are relatively affordable, representing less than 5% of GDP per capita, which explains why a larger proportion of students from disadvantaged backgrounds are able to enroll in private schools, unlike in Malawi.

Table 4: Tuition fees for non-religious private primary schools

Source: Author, using Tsimpo and Wodon, 2013, and GDP per capita (constant 2005 dollars) from World Bank statistics for the year of the study.

Note: For Nigeria, Malawi, and Sierra Leone, this is the GDP per capita for 2005, as data for 2003 and 2004 are not available.

In addition to inequalities in terms of economic resources, the private sector is also often marked by gender inequalities. Private schools often remain inaccessible to girls (Aslam, 2009; Härma, 2011; Härma and Rose, 2012; Nishimura and Yamano, 2013). Indeed, among the poorest households, the scarcity of resources means that parents cannot send all their children to private school. They therefore often choose to enroll boys instead, as they will benefit more from the return on educational investment in the labor market (Härma, 2011). If no measures are taken to reform this system, the current expansion of private schools will not be able to reduce gender gaps in access to education.

Conclusion

Despite some notable progress, many countries are still far from achieving the goal of Education for All. Public schools in many countries are unable to meet demand in terms of both quantity and quality, which explains the rise of the private sector.

While in theory the development of private schools could help to compensate for certain shortcomings in the public sector, the fact remains that in many countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, private schools are still reserved for an elite. Without appropriate policies, this situation will lead to increased inequality in the coming decades.

It is therefore necessary to reform public schools in order to avoid exacerbating inequalities and to ensure that all children receive a quality education (EFA Global Monitoring Report, 2009, 2013). It would be beneficial for all to consider creating partnerships between the government and private institutions (Dyer and Rose, 2005; Rose, 2006).

Notes:

[1] In addition, some private schools are not registered and therefore do not appear in official statistics.

[2] French and Kingdon (2010) compare the differences in academic results between two or more children from the same household but attending private or public schools. After controlling for multiple unobservable characteristics, they estimate that, on average, children attending private schools score 0.33 standard deviations higher on exams than those attending public schools.

References:

– Andrabi, T., Das, J., and Khwaja The rise of private schooling in Pakistan (2002): catering to the urban elite or educating the rural poor? World Bank and Harvard University

– Andrabi T., Das J., Khwaja AI. (2008), A dime a day: the possibilities and limits of private schooling in Pakistan., Comparative Education Review 52 : 329–355.

– Aslam M. (2009), The relative effectiveness of government and private schools in Pakistan: are girls worse off?, Education Economics 17 (3): 329–354.

– Aslam M., Kingdon G. (2011), What can teachers do to raise pupil achievement?, Economics of Education Review 30 (3): 559–574

– Colclough C. (1996), Education and the market: which parts of the neo-liberal solution are correct?, World Development 24 (4): 589–610

– Dyer C., Rose P. (2005), Decentralization for educational development? An editorial introduction. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 35 (2): 105–113.

– EFA Global Monitoring Report (2009),Overcoming inequality: why governance matters, Paris: UNESCO.

– EFA Global Monitoring Report (2013), Policy Paper 9. Paris: UNESCO.

– French, R., Kingdon, G. (2010), The relative effectiveness of private and government schools in rural India: Evidence from ASER data, London: Institute of Education

– Friedman, M. (1955), The role of government in education, Rutgers University Press

– Glick, P., Sahn D. E. (2006), The Demand for Primary Schooling in Madagascar: Price, Quality, and the Choice between Public and Private Providers, Journal of Development Economics, 79(1):118-145

– Härmä, J. (2011), Low cost private schooling in India: Is it pro poor and equitable?, Journal of Educational Development, 31(4):350-356

– Härmä J, Rose P (2012), Is low-fee private primary schooling affordable for the poor? Evidence from rural India., In: Robertson R, Mundy K (eds) Public-private partnerships in education: new actors and modes of governance in a globalizing world, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

– Holmes, G.M., DeSimone, J., Rupp, N. G., (2003), Does School Choice Increase School Quality?, National Bureau of Economic Research

– Heyneman SP., Stern, JMB. (2013), Low cost private schools for the poor: what public policy is appropriate? International Journal of Educational Development

– Kitaev I. (1999), Private education in sub-Saharan Africa: a re-examination of theories and concepts related to its development and finance. Paris: UNESCO-IIEP.

– Kingdon G. (1996), Private Schooling in India: Size, Nature and Equity-Effect. Economic and Political Weekly: 3306-3314

– Kingdon G. (2008), School-Sector Effects on Student Achievement in India,School Choice International: Exploring Public-Private Partnerships: 111-142

– Kingdon G., Banerji R. (2009) Addressing school quality: some policy pointers from rural north India., Cambridge: Research Consortium on Educational Outcomes and Poverty (RECOUP).

– Kremer M., Muralidharan K. (2008), Public and private schools in rural India. In: Peterson P, Chakrabarti R (eds) School choice international. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

– Latham M. (2002), A handbook on private sector participation in education: a review of possible ways and means, Reading : CfBT with the World Bank.

– Lewis L., Patrinos HA. (2012), Impact evaluation of private sector participation in education. London: CfBT Education Trust.

– Muralidharan K., Kremer M., Sundararaman V. (2011), The aggregate effect of school choice – evidence from a two-stage experiment in India. Cambridge, MA: The National Bureau of Economic Research. Working paper no. 19441

– United Nations, 2014. « Millennium Development Goals. Report 2014 » Report, UNPD.

– Nishimura M., Yamano T. (2013), Emerging private education in Africa: determinants of school choice in rural Kenya, World Development 43 : 266–275

– Rose, P. (2006), Collaborating in education for all? Experiences of government for non-state provision of basic education in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, Public Administration and Development, 26(3): 219-229

– Singh, R., Sarkar S. (2012), Teaching quality counts: how student outcomes relate to quality of teaching in private and public schools in India., Oxford: University of Oxford. Young Lives Working Paper 91

– Tooley J., Dixon P. (2003), Private schools for the poor: a case study from India, London : CfBT

– Tooley J., Dixon P. (2007), Private schooling for low-income families: a census and comparative study in East Delhi, India, Oxford Studies in Comparative Education, 17 (2): 15

-Tooley J., Bao Y., Dixon P., Merrifield J. (2011), School Choice and academic performance: some evidence from developing countries., Journal of School Choice 5 (1): 1–39.

– Tsimpo C., Wodon Q., (2013), “Assessing the Role of Faith-Inspired Primary and Secondary Schools in

Africa: Evidence from Multi-Purpose Surveys.”, Mimeo, World Bank, Washington, DC.