Summary:

– Contrary to popular belief, negative interest rates do not affect credit according to the « stick » principle, whereby banks are encouraged to invest their cash in the real economy so as not to be « punished » by negative interest rates on their own accounts at the central bank.

– This paradigm stems from a common misconception, recently raised by the Bank of England, that banks lend the cash they hold in their accounts at the central bank to households or businesses, and that by making a loan they can « get rid of » it » and escape the « tax » represented by the negative interest rate: this is not the case at all.

. Even setting aside this confusion, in theory the incentive effect of lowering the interest rate on deposits below 0 may prove negative and lead to a reduction or stagnation in credit rather than an increase

– The ECB did not implement this measure in the hope of directly encouraging banks to lend more, as has often been suggested recently. The main effect of this measure was widely expected to be on exchange rates, with the effect on credit likely to be only indirect, by helping to defragment the eurozone

Taxing excess reserves via a negative interest rate does not mean that banks will be directly encouraged to offer more credit to businesses, as is often claimed; the theoretical effect may even be the opposite. The ECB did not design this measure with this channel in mind.

« Until now, commercial banks have been in the habit of stashing away huge sums of money in the ECB’s vaults in Brussels, money that they were not, of course, lending to businesses or households. Well, the negative rate means that from now on they will have to pay to do so, which should discourage them, and it is therefore in their interest to put these sums into the economy, »

saida journalist from a major French TV channel on the 8 p.m. news on Thursday, June 6.

« By lowering its deposit rate to a negative level, the ECB hopes to encourage banks to lend more to businesses and households. »

A journalist from an economic weekly on Wednesday, June 5

« From journalists, former colleagues, and professors at Harvard, Yale, and Columbia, I have been reading the same ideas/comments for almost five years. Namely, that in one way or another, banks’ reserves at the central bank are supposed to be ‘lent out,’ that is, leave the Fed or ECB vault and start circulating in the economy. » . » « Naturally, this surprisingly incorrect conceptualization of the credit process (…) leads people to think about how to encourage banks to ‘take their money out of the vaults,’ including considering negative interest rates as an incentive tool. »

Former Director of the Monetary Policy and Central Banking Department at the IMF

On July 5, the ECB took a historic step by lowering one of its key interest rates, the deposit rate, below 0. This original policy has sparked numerous comments, many of which, like those cited above, reveal significant confusion about this measure. No, negative interest rates do not affect credit according to the « stick » principle, whereby banks would be encouraged to place their cash in the real economy so as not to be « punished » by negative interest rates on their own accounts at the central bank. This assertion makes no sense. We explain why in the first part. In theory, the opposite incentive effect could occur: a negative deposit rate would likely have a restrictive effect on bank lending in situations of excess reserves, if not insignificant. The slightly negative deposit rate set by the ECB was certainly not intended as a direct incentive for lending, contrary to what has often been claimed recently.

Confusion

The confusion we are pointing out here is based on the following reasoning. Suppose a person has €1,000 in their bank account. This person prefers to keep their €1,000 safely in their bank rather than take the risk of lending it to you at a given interest rate. If this person’s bank now decides to tax bank deposits at 1% (via a negative interest rate of -1%), then the person in question will think twice before putting their money in the bank… This person will have an additional incentive to lend it to you, as you are offering them a positive interest rate in exchange for their money. This is perfectly fair in itself.

Now, instead of this person, imagine a French commercial bank. Instead of this person’s bank, imagine the European Central Bank. And instead of you, imagine an SME in need of credit. If we repeat the previous reasoning, we will be led to think the following: negative interest rates will encourage banks, including French commercial banks, to take their money out of their vaults and lend it to SMEs. This is the meaning of the journalist’s comments above, who explains that banks » used to keeptheir money safe in the ECB’s vaults, »[1]which « of course, was not lent to businesses, » and therefore, with negative rates, they would now have an incentive to« invest these sums in the economy. » Sounds appealing, doesn’t it? But it‘s misleading: there can be no such incentive effect, since a loan for a bank does not result in a transfer of cash, as is the case with a loan between two individuals.

When a bank grants a loan to a household or a business, it simply credits the account of the household or business to which it has granted the loan: it is a simple accounting entry. Under no circumstances will the transaction result in a transfer of cash from the bank to the household; the bank’s money will remain in the ECB’s vaults, for the sole reason that a household or SME cannot have an account with the central bank.[2]. Let’s look at the accounting transaction corresponding to a loan made by this French bank to an SME.

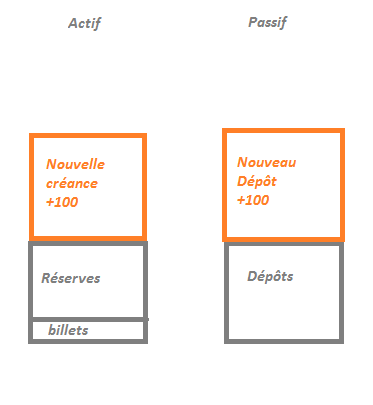

- The transaction for the SME:the SME receives a loan from the bank. The SME’s account with the bank increases by €100, and the SME now owes €100 to its bank.

The SME

- The transaction for the bank:it now has an additional deposit of €100 on its liabilities side and a claim on the SME of €100 on its assets side.

Commercial bank

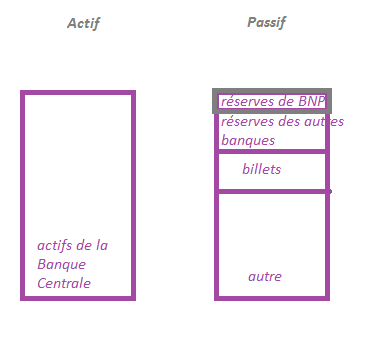

The bank’s reserves (i.e., the money it holds in its account at the Central Bank) have not changed as a result of this transaction.[3] !

Central bank balance sheet unchanged: (example with BNP bank)

BEFORE AFTER

A loan to a household or business therefore has no impact on the cash holdings of a bank at the central bank: if the bank grants such a loan, it does not dispose of any of its reserves. We cannot therefore expect banks to lend to households or businesses in order to dispose of the cash they hold in their accounts at the central bank, which is « taxed » via a negative interest rate: granting a loan to a household or business will in no way change the bank’s situation, which will remain subject to this « tax » on its cash holdings.[4]. The idea that a bank’s cash could leave the ECB’s vaults via a credit transaction is a misconception that is apparently very popular, if we are to believe the article by the Bank of England (available here).

A potentially negative theoretical impact on credit

We have shown that banks cannot transfer liquidity to households or businesses to escape the negative interest rate « tax. » But could banks with liquidity « safely tucked away » at the ECB theoretically be encouraged to finance the economy more through another channel as a result of these negative rates? The answer is far from obvious, and it seems more realistic to assume that the effect is, on the contrary, counterproductive for credit.

With negative deposit rates, each bank with excess liquidity in its account at the central bank must pay an amount equal to 0.01% of that excess liquidity. This is currently the case for many German banks, for example. Banks will pay interest on their deposits at the central bank, which will in itself reduce their margin on their daily operations. A loan to an SME that was profitable at a rate of 6%, for example, will now be less profitable due to this constraint on the bank’s deposits. To maintain the same profitability, the bank could therefore increase the rates it offers on its SME loans , which would reduce demand for credit. This was noted in BNP Paribas’ economic research in a 2013 note » banks may decide to pass on to borrowers the increased costs resulting from negative deposit rates , » an option also mentioned by Crédit Agricole CIB research. This possibility could arise if banks do not pass on the increase in their costs to their customers’ demand deposits. This did not happen in Denmark, for example[5], where, according to Crédit Agricole CIB’s economic research (see references below), the costs were indeed passed on to new borrowers. In no case would the effect be positive in this context.

Again, if costs are not passed on to depositors, one could object to the above reasoning on the grounds that this measure could encourage banks to take greater risks in order to maintain their profitability, i.e., by lending to companies or households that are considered more risky. This seems illusory for several reasons.

First, this argument is difficult to sustain in the current context, where it is often said that prudential ratios constrain banks in their credit allocation, and where profitability is not really undermined for banks in the « core » countries of the euro area, which hold excess reserves.

Second, and more importantly, this would mean that banks would be taking on more risk for the same level of profitability. In other words, they would be taking risks that would not pay off, which seems incongruous to anyone familiar with the financial world. This is especially true given that opportunities to take « profitable » risks would still exist outside of lending to households and businesses (e.g., through the purchase of securities from other banks or the lending of cash to other banks carrying risks[6]). Recent comments by the co-chairman of Deutsche Bank (link here) directly support our argument: « We are not going to lend because the central bank is threatening to charge you a penalty on your deposits. That is ridiculous and would create a new crisis, » before pointing outthat « banks will base their lending decisions primarily on the creditworthiness of borrowers. » Both in theory and in practice, therefore, it seems unrealistic to think that banks will take more risks in their lending decisions to households and businesses as a result of this measure.

If banks holding excess reserves now pass on their costs to their depositors, we cannot expect any particular direct effect on credit. Borrowing rates should remain unaffected by the fall in the deposit rate into negative territory in this context.

It is therefore clear that the usual assertion that a negative deposit rate would act as a « stick » to encourage banks to finance the economy is not as obvious as it seems, and may even be completely at odds with reality.

The impact of negative interest rates is to be found elsewhere

It seems unrealistic to view negative rates as a measure designed to encourage banks with excess reserves to lend to households and businesses. However, this does not mean that the measure decided by the ECB is theoretically useless for credit. It could have an impact for reasons other than the pseudo « incentive effect » highlighted by some media outlets. The positive impact of this measure on lending could be indirect, linked to the specific characteristics of the eurozone.

Banks in peripheral countries are generally not those with excess reserves.[7], and in this respect the measure could have a positive impact on their economies. Banks in countries with excess reserves could in fact be more inclined to lend their liquidity to banks in need of liquidity, mainly those in peripheral countries, since this operation effectively results in a transfer of liquidity, thus avoiding the « tax » of negative interest rates. These banks could therefore benefit from more advantageous refinancing conditions and less stringent liquidity constraints (see the Natixis documentdocument on the importance of this last point at present), which would have a positive impact on their situation and their credit supply.

Similarly, banks in core countries could be encouraged to purchase liquid private or public debt securities from peripheral countries, which offer higher returns than securities on their domestic market, in order to avoid this tax, thereby substituting their reserves for other liquid, high-yielding assets[8]. This is a scenario envisaged in particular by the economic research departments of Crédit Agricole CIB and BNP Paribas, with the latter writing that « institutions in the ‘center’ could once again find it opportune to invest this liquidity in peripheral countries. » This could ease monetary and financial conditions in peripheral countries, which need this more than countries in the « center » of the eurozone.

These two effects would therefore lead to more favorable credit conditions in peripheral countries, and in this respect negative deposit rates would indeed have a theoretically positive impact on credit in the eurozone, albeit indirectly. At the same time, this would also contribute to the financial defragmentation of the eurozone by reviving financial flows from the center to the periphery. Finally, it should be noted that if banks in the core countries choose to pass on the costs of holding their excess reserves to their depositors, this could have positive effects for the eurozone by increasing demand and discouraging savings in the core countries.

Conclusion

It is therefore clear that the assertion that a negative deposit rate would act as a stick to encourage banks to finance the economy does not make sense. It does not make sense because banks do not dispose of their liquidity through lending, and because there is no particular reason why the incentive effect should be positive for the banks concerned. Theoretically, it seems even more accurate to think that such a measure would have a restrictive effect on lending for banks with excess reserves. In practice, if we try to make sense of the usual argument about the incentive effect, it would lead us to conclude that banks in core countries with excess reserves will increase their risk-taking in order to maintain their profitability. This argument has been described as « grotesque » by the co-chairman of Deutsche Bank, and is difficult to sustain both theoretically and in practice, in a context where prudential regulation constrains the risk-taking of banks themselves, which are often described as fragile in the eurozone.

However, this measure could have indirect positive effects on credit, due to the specific characteristics of the eurozone. A positive effect could be observed where banks do not have excess reserves, particularly in peripheral countries.

In general, a revival of credit in the eurozone is certainly not to be expected directly from this measure, but rather from other measures decided by the ECB, such as fixed-rate LTROs or the reduction of the main policy rate to 0.15%. For many economists, the main impact of the negative deposit rate measure concerns the exchange rate: the negative rate is supposed to encourage capital withdrawals from the eurozone and thus lead to a depreciation of the exchange rate. And not credit, as is too often repeated.

References

– « Money creation in the modern economy, » Michael McLeay, Amar Radia, and Ryland Thomas, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2014 (an article that is definitely worth reading): http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf

– Comments by Jens Weidman on negative interest rates, confirming that the expected effect is on exchange rates rather than credit http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/03/25/us-ecb-weidmann-idUSBREA2O15H20140325

– Comments by the co-chairman of Deutsche Bank: « Negative ECB rates won’t spur lending – German banks, » Reuters: http://uk.reuters.com/article/2013/11/22/europe-banks-rates-idUKL5N0J72KD20131122

– Natixis Economic Flash, June 13, 2014 « Is bank behavior still holding back growth in the eurozone? »:http://cib.natixis.com/flushdoc.aspx?id=77312

– BNP Paribas CIB, November 2013 « The ECB in exploratory mode » http://ecodico.bnpparibas.com/Views/DisplayPublication.aspx?type=document&IdPdf=23294

– Crédit Agricole CIB, « The ‘known unknowns’ of a negative deposit rate » https://catalystresearch.ca-cib.com/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=f441cf52-345c-440c-a335-6fb13f7b357d&groupId=10138

For further reading:

– Post by a member of the New York FeD on a debate not addressed here, the negative consequences of a negative rate on the payment system:http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2012/08/if-interest-rates-go-negative-or-be-careful-what-you-wish-for.html#.U5oDCChRaHc

Notes:

[1] It should be noted that this statement is not entirely accurate, as banks hold their cash reserves in their respective national central banks. However, this does not alter the reasoning and remains an acceptable simplification.

[2]Only banks and the Treasury can have an account with a central bank.

[3]See the Bank of England article in the references for further explanation, or the highly informative book on this subject, Money, Banking, and Finance Markets by F. Mishkin.

[4]We have deliberately left out one element whose impact is completely negligible here: reserve requirements. These reserve requirements do earn interest, but account for only 1% of deposits. In other words, if a bank makes a loan, it will continue to pay a negative interest rate on 99% of the amount of the new deposit and will only receive interest on 1% of that amount, which is completely negligible in practice.

[5]See the June 4, 2014 print edition of the Financial Times and the Crédit Agricole CIB publication in references.

[6]

[6]By doing so, the bank would effectively dispose of its cash reserves and thus avoid the negative interest rate « tax » on those reserves. There would be no « hot potato » effect, as the banks receiving the cash reserves would not be in a position of excess reserves.

[7]These are the banks that most often borrow from the ECB, whereas banks in the « core » countries used to place their cash in term deposits offered by the ECB as part of the sterilization of the SMP in the days leading up to the discontinuation of this measure.

[8]Technically: if the securities are purchased from other banks or from the customers of those other banks.