Usefulness of the article: Understanding the conclusions of the work carried out by the Pension Advisory Council (COR) in order to form an opinion on the issue of raising the retirement age.

Summary:

- The aging population is putting pressure on the French pension system.

- The pension system is expected to show controlled deficits between 2025 and 2045, before becoming surplus between 2045 and 2070. The financial sustainability of the system therefore does not appear to be under threat.

- Nevertheless, the controlled trajectory of public spending on pensions is only possible through a deterioration in the relative standard of living of pensioners. Individual retirement pensions are set to decline gradually until 2070 in relation to wages, due to laws passed in the 1990s and 2000s that ended the indexation of retirement pensions to wages.

- Raising the retirement age appears to be a political choice. It would be appropriate to consider the appropriate level of individual retirement pensions before any decision is made.

President E. Macron wants to raise the legal retirement age from 62 to 65, believing that the aging population makes his reform plan inevitable. Emphasizing the necessity of the reform, Prime Minister E. Borne even stated on September 26, 2022, « I invite all those who pretend to believe that there is no problem with the pension system deficit to read the report of the Pension Advisory Council (COR). » With this statement, she was responding to those who oppose such a reform and who, while citing the same report, claim that the famous « hole in the pension system » that the executive branch is seeking to fill does not exist. What is the reality of the situation?

I/ A pension system under pressure from demographic changes

1/ Since the end of World War II, the proportion of the population aged over 60 has been steadily increasing, threatening the financial stability of the French pension system. The aging population is increasing the number of pensioners relative to the number of contributors. While there were 2.1 active contributors for every retiree in 2000, the number of contributors per retiree is now 1.7 and is expected to reach 1.3 or even 1.2 in 2070. This raises the question of the financial viability of our pay-as-you-go pension system.

This system is based on intergenerational solidarity, whereby retirees’ pensions are paid for by contributions made in the same year by the working population. When the number of retirees increases faster than the number of working people, the « rules of the game » need to be changed in order to preserve the balance of the system so that resources (mainly social security contributions) match expenditure (retirement pensions). The government then has three levers of action at its disposal:

- raising the retirement age

- reduce the amount of pensions

- increase social security contributions

2/ Since the 1980s, a series of pension reforms has used the first two levers mentioned above—lowering pensions and raising the retirement age—to solve the « pension problem »(notably the Balladur reforms in 1993, Fillon in 2003, Woerth in 2010, Touraine in 2014)[1].

On the one hand, these reforms raised the average retirement age through changes to: i) the legal retirement age (raised from 60 to 62), and ii) the minimum number of years of contributions required to receive a full pension. The average retirement age has thus risen from 60.7 in 2000 to 62.3 in 2020 and is expected to reach nearly 64 in 2035, according to the COR. It should be noted, however, that the length of time spent in retirement has increased slightly since the early 2000s due to longer life expectancy.

On the other hand, these reforms have reduced the amount of retirement pensions:

– Retirement pensions have decreased in absolute terms due to the increase in the period taken into account to determine the reference salary in the calculation of retirement pensions from 10 to 25 years in the private sector.

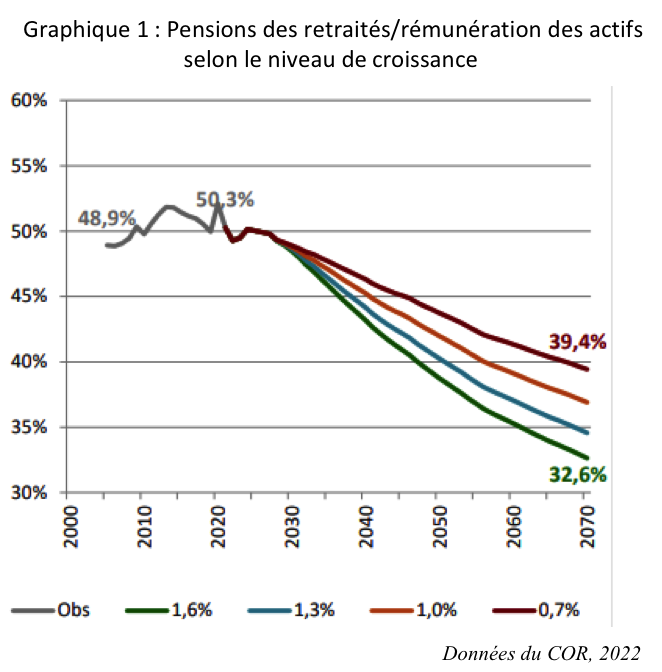

– Retirement pensions have decreased in relative terms (compared to workers’ salaries) through the indexation of retirement pensions to prices, whereas they were previously indexed to salaries. In fact, with few exceptions, wages increase faster than prices in the long term. This change in legislation will gradually increase the decline in the standard of living of new retirees and will contribute to creating a growing gap in the standard of living between retirees and employees. In other words, the end of the indexation of pensions to wages excludes retirees from sharing in the increase in wealth produced each year (economic growth), making them relatively poorer than workers. This is shown by the COR figures (see Figure 1). The average pension of a retiree is currently around 50% of the remuneration of a working person, a proportion that will fall to between 33% and 39% of the remuneration of a working person in 2070 if the legislation does not change.

3/ However, despite these reforms, the pension system is expected to run deficits over the period 2025-2045. Although it will be in balance in 2021, the pension system’s balance is expected to deteriorate in the coming years due, on the one hand, to the continued presence and retirement of baby boomers since 2006 and, on the other hand, to the diluted impact over several decades of the reforms carried out between 1993 and 2014, which have not yet had their full effect.

II/ However, the stability of the pension system does not appear to be under threat.

1/ In the long term, the financial stability of the pension system appears to be assured. Once the period 2025-2045 has passed, the COR expects the financial balance of the pension system to return to equilibrium. The deficit forecast for the period 2025-2045 is expected to be absorbed by the measures taken over the last forty years.

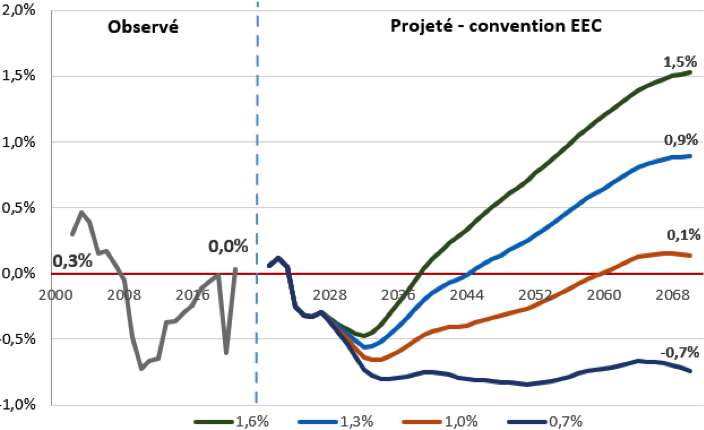

To forecast the evolution of the pension system’s balance by 2070, the COR has identified four scenarios based on the anticipated average economic growth rate (+0.7%, +1%, +1.3% and +1.6%)—i.e., the rate at which the wealth produced annually in France increases. The results of the projections are shown in Figure 2. This shows that:

– In three out of four scenarios, the pension system will run deficits before returning to equilibrium.

– The higher the level of growth, the faster the pension system will return to equilibrium: as early as 2037 in the +1.6% growth scenario (the most favorable scenario), from 2043 in the +1.3% growth scenario, and from 2058 in the +1% growth scenario. However, in the +0.7% growth scenario (the most unfavorable), equilibrium is never restored.

– In none of the scenarios would the pension system deficit exceed 0.8% of GDP per year.

Thus, the COR estimates that « changes in the share of pension expenditure in GDP would remain on a controlled trajectory until […] 2070 »[2].

Figure 2: Pension system balance (as a percentage of GDP)[3]

COR data, 2022

2/ In the short term, the financial stability of the pension system does not appear to be threatened by the deficits expected for the period 2025-2045 if there is no change in the retirement age. In each of the COR scenarios, the pension system deficit never exceeds 0.8% of GDP over a single year. This amount is insufficient to destabilize the system for at least two reasons.

First, two major available resources have not yet been exploited to fill these deficits:

- On the one hand, the various pension schemes have accumulated reserves in the past to cover their financial needs. They have thus anticipated the temporary demographic difficulties associated with the baby boom. In 2022, the net reserves of the various pension schemes will amount to €163 billion, or 6.5% of GDP (an amount sufficient to cover the deficits in the 1.6% and 1.3% growth scenarios). However, this solution would require pension funds with surpluses to « agree » to share their savings with funds in deficit.

- On the other hand, the government will soon have significant new leeway to finance the pension system. Since 1996, part of the debt of the various branches of social security has been placed in an organization called the Caisse d’Amortissement de la Dette Sociale (CADES). CADES, whose mission is to repay the debt it has taken on using resources from part of the CSG-CRDS, will have fulfilled its objective in 2024. This will free up €24 billion per year (nearly 1% of GDP each year—enough to cover the annual deficits of the pension system in all the scenarios mentioned above) which, according to former Finance Minister Christian Eckert, could be used to finance the old-age branch of social security.

Secondly, the government could also activate a lever that has been largely neglected until now to make up for the temporary deficits in the pension system: increasing social security contributions. In 2021, the contribution rate stands at 31.2% of earned income. According to the COR, in the worst-case scenario, where annual growth would only reach 0.7%, this rate would have to be raised to 32.1% (+0.9 points) on average over the next 25 years in order to achieve balance each year during this difficult period. Smoothed out over several years, such an increase would be relatively imperceptible to workers, who would continue to see their incomes rise—albeit at a slightly slower pace—along with economic growth.

III/ So, should the retirement age be raised?

1/ At the end of this study, it appears that it would not necessarily be « necessary » to raise the retirement age. Indeed, given the current legislation, no change is absolutely necessary to maintain the balance of the pension system. The main effect of E. Macron’s reform project is to reduce public spending and thus the scope of state intervention in the economy – even though pension expenditure accounts for a quarter of public spending and 14% of GDP (€325 billion in 2018). More specifically, by raising the retirement age without increasing pension amounts, the government would contain or even reduce the weight of pension expenditure in GDP despite the increase in the number of retirees.

2/ However, raising the retirement age could help meet certain objectives if this measure were accompanied by other reforms:

– Revaluing retirement pensions to avoid a significant decline in the relative standard of living of retirees (whose purchasing power is set to stagnate due to the indexation of pensions to inflation, while the wages of the working population are expected to continue to rise faster than inflation in the medium/long term[4]). The COR estimates that while the standard of living of today’s retirees is equivalent to that of the population as a whole, retirees in 2070 will be between 13% and 26% poorer than the population as a whole, depending on the scenario. Although largely overlooked in public debate, this is undoubtedly the most decisive issue: while the viability of the pension system is not threatened by the current legislative framework, this is only true at the cost of a decline in the relative standard of living of retirees.

– Take into account the difference in life expectancy between the wealthiest and the poorest (who spend less time in retirement). In this case, it would be appropriate to raise the retirement age only for the wealthiest[5]. Indeed, someone in the wealthiest 5% of the population has a life expectancy 13 years higher than someone in the poorest 5%, while an executive has a life expectancy 6 years higher than that of a manual worker. Thus, a manual worker spends on average less time in retirement than an executive for the same contribution period.

– Maintain and accumulate reserves to protect the pension system from a severe and sustained economic downturn. Economic growth over the next 50 years is a very difficult variable to predict, and the COR’s least favorable scenario remains rather optimistic (average growth of 0.7% until 2070). Growth forecasts are subject to many uncertainties, such as those related to climate change.

Conclusion

In short, no change in legislation would appear to be so essential as to be absolutely necessary. Projections show that the system is expected to record manageable deficits between 2025 and 2045 before recovering to restore financial equilibrium.

Nevertheless, if « saving the pension system » means « maintaining the performance level of one of the world’s most effective systems for combating poverty among the elderly » (the poverty rate in France is currently lower among retirees than in the rest of the population), then it will be necessary to revalue retirement pensions as they decline[6] due to the deindexation of pensions from wages that began in 1993. However, revaluing retirement pensions could jeopardize the balance of the pension system, thus justifying, for example, an increase in the retirement age.

Bibliography

« COR Annual Report, »Pension Advisory Council, 2021

« COR Annual Report, »Pension Advisory Council, 2022

« An exaggerated aging of the population, »Center for Social Observation, 2021.

« The various pension reforms from 1993 to 2014, »Vie publique, 2018

« Does the pension system have €150 billion in reserves? »,Le Monde, 2019

« Pensions: they’re not telling us everything, »Christian Eckert’s blog, 2019

« Pension reforms: a look back at four recent changes in French society, »BSI Economics, 2019

[1]In brief: Pension reforms between 1993 and 2014

Balladur reform (1993): Annual revaluation of retirement pensions based on price changes rather than wage changes + extension of the contribution period from 37.5 to 40 years in the private sector

Fillon reform (2003):Extension of the contribution period to 41 years in the public and private sectors

Woerth reform (2010): Increase in the age at which an insured person who does not have the required contribution period can still receive a full pension from 65 to 67 + increase in the minimum legal retirement age to 62.

Touraine reform (2014): Increase in the contribution period to 43 years (by …)

[2]The COR nevertheless emphasizes that this observation does not imply any political consideration regarding the current or future level of these expenditures.

[3]State balancing subsidies—which represent 2% of the pension system’s resources—will be deemed unchanged as a percentage of GDP. We therefore use the EEC accounting convention here.

[4]It should be noted that wages may temporarily increase at a slower rate than inflation in an inflationary environment, which in this case favors retirees whose pensions are indexed to inflation rather than wages. In the long term, however, this phenomenon is rare or political (it can be explained in particular by a lasting change in the distribution of added value between labor and capital).

[6]Relative to workers’ wages