Summary

– India has a large labor pool, with more than half of the population under the age of 25. However, India’s economy specializes in « sophisticated » services that create high added value without requiring a large workforce.

– Its economy has strong growth potential with the emergence of a new urban middle class. However, it is still largely rural, and nearly 30% of the population lives below the poverty line.

– The Indian economy remains relatively closed to foreign trade, with a fairly poor business climate and governance. Households and businesses regained confidence after the election of Prime Minister Modi in 2014, believing that he would succeed in liberalizing the economy.

As the world’s second most populous country with 1.25 billion inhabitants, the majority of whom are under the age of 20, India has a sizeable domestic market and also benefits from a large labor pool. In addition to its demographic advantage, India has also experienced significant economic growth since the 2000s, giving rise to an urban middle class that is fluent in English and aspires to a modern lifestyle.

However, inequalities remain high in the country due to the caste system, which is still very much present in Indian culture. Furthermore, the agricultural sector is still underdeveloped and contributes little to economic growth. The lack of infrastructure and cumbersome administrative procedures make the business environment unfavorable to foreign investment.

1. India, an emerging economy with a very specific development model

1.1 An economy specializing in « sophisticated » services

The Indian economy’s development model differs from that of all other emerging countries. The economy specializes in so-called « sophisticated » services. These are high value-added sectors such as insurance, IT, telecommunications, and accounting. These sectors generally require a small but highly skilled workforce. At the same time, the industrial sector, which is generally more labor-intensive than the service sector, remains underdeveloped and contributes only moderately to GDP growth. This development choice seems paradoxical given the country’s considerable labor pool, as the Indian population is mostly made up of young people under the age of 25 with little education (only 25% of young people in secondary education continue on to higher education, compared to a global average of 33%).[1]).

1.2 An economy still relatively closed to foreign trade

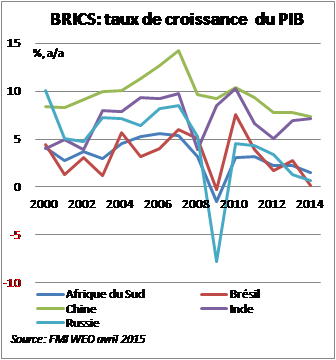

Thus, thanks to its development model based not on foreign trade in goods (Indian economy openness rate: 24% of GDP[2]) but focused on services, India has reported strong growth since 2000, averaging 7% year-on-year. In addition, as exports of « sophisticated » services are less sensitive to changes in global trade, the Indian economy was able to withstand the global crisis of 2009.

However, the catch-up effect that the country enjoyed from the 2000s onwards, thanks to rapid growth in the working population and the emergence of a middle class (GDP per capita in purchasing power parity tripled in ten years), has gradually dissipated. This led to a sharp slowdown in growth from 2011 onwards. The slowdown was also the result of parliamentary paralysis, which significantly affected the effective implementation of the « major » economic reforms India needs to diversify its economy and stabilize its growth trajectory.

2 The Modi effect

2.1 A gloomy pre-election economic situation

Severe political inertia and repeated corruption scandals

The arrival in power of a second coalition, the United Progressive Alliance (UPA), in 2009 was marked by a sharp slowdown in the Indian economy. During his term in office, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh attempted to implement reforms to open up the economy to foreign capital. However, he faced strong opposition on several occasions due to his party’s minority position in Parliament, which also struggled to establish a common position. One example of this is the reform to open up the retail sector to foreign multi-brand retailers. Passed in 2012, this reform does not appear to have had the desired effect. In 2014, given the strict conditions[3]imposed on foreign investors, the Carrefour group decided to close its five stores. These uncertainties about the government’s ability to implement clear economic policies have led foreign investors to turn away from the Indian market in favor of other emerging markets. In addition, businesses and households have gradually lost confidence in the political sphere as multiple corruption scandals within the historic Congress Party have come to light. Corruption is indeed a serious problem in India. According to the World Bank’s governance indicators, India ranks119thout of 181 countries, with no improvement observed over the last 20 years. This significantly hinders the development of the private sector.

A resurgence of inflationary pressures

In addition to this political deadlock, the Indian economy has also experienced a sharp rise in inflation since 2009. It averaged more than 10% between 2009 and 2012. This is mainly due to high commodity prices during this period. To contain this surge in inflation, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) pursued a restrictive monetary policy, which led to a credit crunch and a decline in confidence among businesses and households.

The risk of losing investment grade status

As India is highly dependent on energy imports, the sharp rise in hydrocarbon prices after the 2009 crisis significantly worsened the current account deficit. The latter reached a historic high in 2012 at nearly 5% of GDP. As a result, the marketsare considering the risk ofIndia losing itsinvestment grade status, given the worsening macroeconomic imbalances, renewed inflationary pressures, and significant uncertainty about the government’s ability to implement reforms. These sources of uncertainty were exacerbated in the run-up to the May 2014 presidential elections.

2.2 The success of Modi’s « pro-business » election rhetoric

The Gujarat economic « miracle »[4] and Modi’s promises of « pro-business » reforms

Elected Chief Minister of Gujarat in 2002, Modi transformed the region into a veritable industrial hub by launching a vast infrastructure modernization program. This attracted many foreign investors, and the region’s growth rate rose well above the national average.

During his election campaign, Modi promised to replicate this « success » on a national scale. He also won over investors by emphasizing the need to curb corruption within the central administration. Finally, he benefited from significant pre-election media coverage.

Results exceeding all expectations

Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP, a right-wing nationalist party opposed to the historic Congress Party) and its alliance parties won 316 seats in the lower house of Parliament (Lok Sabha), compared with 50 for the main opposition party, the Congress Party. Modi thus secured a majority in the Assembly. This was a strong signal to the financial markets, which welcomed the news: the Indian rupee appreciated slightly after the election results.

3. A more favorable economic environment

3.1 The lifting of external constraints

In a global economic context marked by falling oil prices, India enjoyed a slight rebound in growth to +7.3% in 2014/2015. This rebound was partly attributable to a change in the base year used to estimate GDP growth. The recovery is expected to continue in 2015/2016: India is expected to overtake China and achieve GDP growth of 7.5% (Chinese growth is estimated at 6.8% for 2015 according to the IMF, although this figure is likely to be even lower). This growth will be driven mainly by increased investment spending on infrastructure and a recovery in exports of goods and services.

In terms of external accounts, India mainly exports raw materials (oil, diamonds, and agricultural products) and manufactured goods to Europe (16% of the country’s total exports), the United States (12%), and ASEAN (11%).As the country is energy dependent, it mainly imports refined oil and gold. Its merchandise trade balance is structurally in deficit, standing at 4.9% of GDP in 2014. Although services account for 30% of total exports, they are not enough to cover this trade deficit. As a result, the current account deficit stood at 2.7% of GDP between 2007 and 2013. Given its limited openness to foreign capital, this current account deficit has been financed largely by external debt. Total external debt nearly doubled in five years, rising from USD 254 billion to USD 436 billion in 2013, or nearly 100% of total exports.

Nevertheless, this current account deficit fell sharply in 2014, reaching only 1% of GDP. This is mainly due to the fall in world crude oil prices. Furthermore, foreign exchange reserves remained virtually stable in 2014, at just over five months of imports. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) therefore has the capacity to intervene in the short term in the event of an external shock. The risk associated with changes in the balance of payments has fallen sharply with the lifting of external constraints. However, caution remains warranted given the rapid rise in total external debt. With public external debt financed mainly by long-term, low-interest loans, the risk lies primarily in the over-indebtedness of private companies.

3.2 A proactive central bank

Inflation fell significantly in 2014, from 10% in 2011 to less than 7% today. The current rate is below the upper limit of the fluctuation band authorized by the Central Bank (6-8%). The fall in oil prices has had the effect of increasing downward pressure on the general price level. To a lesser extent, the appreciation of the Indian currency against the dollar after the presidential elections has also led to a fall in the prices of imported goods. In this favorable environment, the Indian Central Bank reacted quickly by lowering its key interest rate several times starting in December 2014. It could make another cut by the end of the year if commodity prices remain low and the Indian rupee’s depreciation against the dollar remains contained.

3.3 A gradual easing of the budget deficit

India has a structural budget deficit, averaging more than 4% of GDP due to high spending on subsidies for food, energy, and fertilizers. This is also due to the inability of states to collect sufficiently high tax revenues. Nevertheless, the budget deficit for the 2015/2016 fiscal year was revised slightly downward due to the elimination of fuel subsidy expenditures. Public debt averages more than 60% of GDP, a level considered worrying for an emerging country. However, this debt, which is mainly domestic, is essentially financed by national banks. Indeed, the latter are required to hold a certain number of government securities in their assets.

The renewed confidence in the private sector is therefore mainly linked to a more favorable economic environment. Nevertheless, efforts are still needed to stimulate growth potential in terms of improving governance, access to financial services, and poverty reduction.

4. A mixed picture for his first year in office

After the elections, Prime Minister Modi launched a vast industrialization program called « Make in India » with the aim of attracting foreign investors. This would bring real prospects for growth and employment in industry. However, progress on pro-business reforms appears to be slow. Modi faces fierce opposition in the upper house of parliament (Rajya Sabha), where the Congress Party still wields considerable influence.

4.1 Mixed results from the first parliamentary sessions

While no progress was made during the first parliamentary session, the reform to open up the insurance sector was adopted during the second parliamentary session. This measure allows the ceiling for foreign direct investment to be raised from 26% to 49%. However, the reform on the unification of VAT on goods and services was recently postponed until September 2015. The opposition has indicated that it is generally in favor of this measure. However, even if an agreement is reached, this measure[5]would not take effect until 2016. Finally, uncertainties remain regarding agrarian reform. The latter aims to facilitate the acquisition of land for infrastructure projects. However, the opposition is strongly opposed to it given the social impact it could have on many farmers. In an attempt to find a solution, a parliamentary committee, comprising members of the upper and lower houses of Parliament, has been set up and is expected to give its opinion at the end of the year.

4.2 An ambiguous interpretation of the 2015/2016 Finance Bill

According to the 2015/2016 Finance Act, GDP growth is forecast at 8.5%. However, this figure seems a little too ambitious in view of the IMF’s growth forecasts. The budget deficit has been revised slightly downwards due to the removal of fuel subsidies. However, the government could reverse this decision if oil prices rise again. Fuel subsidies are vital for the poorest households as they guarantee their access to energy (one-third of the population still lives below the poverty line according to World Bank data). In addition, the government has planned to reduce corporate taxation by lowering the tax rate on profits from 30% to 25% over the next four years. This measure appears to be favorable to investment but will not solve the problem of consolidating budget revenues in the short term.

Conclusion

Looking back on this first year in office, conditions appear too fragile to confirm a real recovery in Indian growth in 2015. Moreover, the second-quarter growth figure does not indicate a real acceleration in the pace of growth. The release of this figure comes at a time when Modi is facing major protests in his own political stronghold, the state of Gujarat.

[2] The openness of an economy is measured by exports of goods and services as a percentage of GDP (source: World Bank)

[3] Foreign investors are required to form joint ventures with Indian partners, obtain authorization from the Indian government, etc.

[4] This model of success has been strongly contested by economists such as Amartya Sen due to the region’s poor performance in terms of human development.

[5] If adopted, this reform will still need to be ratified by 50% of the states and receive the president’s approval.