At the end of March 2013, the ECB expanded the collateral accepted for Eurosystem liquidity operations ( as part of bank financing) to include non-investment grade sovereign bonds (rated between BB+ and BB-), which particularly affected Greece and Portugal. As it cannot normally bear credit risk on its balance sheet, the ECB’s action was aimed at granting a two-year exemption (until February 28, 2015) in order to directly finance Greek and Portuguese banks and thus indirectly the countries in question.

As of December 31, 2014, Greek banks had borrowed €56 billion from the Eurosystem. To finance these loans, the banks provided the following collateral:

– Greek sovereign bonds: €8 billion (including €3.5 billion in T-Bills).

– « Pillar I and Pillar II » securities, mainly uncoveredbonds issued by banks and guaranteed by the Greek government: €25 billion

– EFSF bonds: €17 billion

– Other securities worth €6 billion

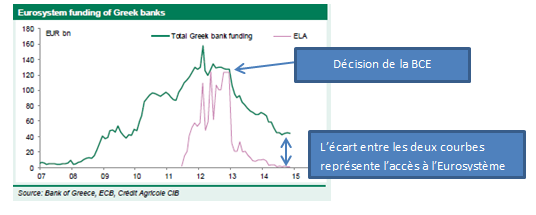

In light of the political uncertainty surrounding an agreement on the financing of Greece by its creditors (IMF, ECB, EFSF, Member States), on February 5, 2015, the ECB decided to end this « exceptional » derogation for Greece (in line with its mandate). Sovereign bonds and « Pillar II and Pillar III » bonds are no longer accepted as collateral by the ECB in Eurosystem financing operations. These securities represent €33 billion, or 15% of Greek banks’ financing needs, according to CACIB. The rest of the financing comes mainly from deposits (and therefore, deposit flight means financing risk…). It is important to note that the ECB has decided to act ahead of schedule, which shows a desire to speed up the negotiation process between Greece and its creditors (we can recall the similar case of Ireland in 2008).In fact, the exception allowing Greek collateral to be accepted was due to end on February 28, 2015, in any case. This is the second time that Greek sovereign bonds have been ineligible for Eurosystem liquidity operations.

In order to ensure the continuity of bank financing, banks will now turn to the Central Bank of Greece via the Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) system . However, while the rules on collateral are set by the Central Bank itself (which therefore accepts Greek sovereign bonds), there is a clear difference between the rates offered by the ECB (0.05%) and those offered by the ELA (1.95%). This differential will have an impact on banks’ financing conditions since, as we have seen, 15% of the Greek banking system’s financing needs must go through the ELA.

Between 2011 and 2013 (before the ECB’s decision to accept non-investment grade securities), Greek banks, which did not have access to the Eurosystem due to the massive downgrade of Greece’s sovereign rating, had already obtained massive financing from the Bank of Greece:

The decision highlights two major risks:

– Banks have a very strong need for liquidity in the wake of the significant increase in deposit outflows over the past two months, which is expected to continue (-€5 billion in December 2014, with -€11 billion anticipated in January). In fact, the significantly less favorable interest rate conditions will weigh on banks’ balance sheets. The Greek banking system is therefore not facing a solvency crisis, but rather a liquidity crisis.

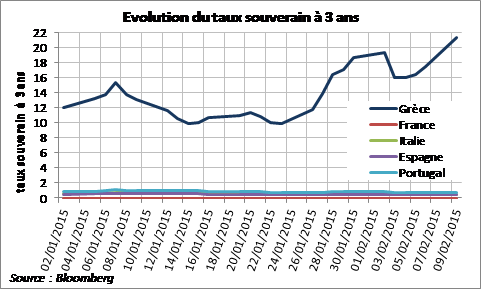

– The ECB retains control over ELA and therefore over Greek banks’ access to financing, since ELA operations exceeding €2 billion require the approval of the ECB’s Governing Council (two-thirds majority). The ECB could therefore cut off all funding to Greek banks at any time. The political risk therefore remains significant and should force the Tsipras government to reach a quick agreement with the Troika. This is particularly true given that without access to the long-term financing market and without credit from the IMF, the country can only finance itself by issuing short-term debt. Once Greek securities are no longer accepted as collateral, demand for these securities will collapse (hence the rise in the 3-year sovereign rate from 16% to 21.3% between February 4, 2015, and February 9, 2015, an increase of +530bp).

However, Greek banks still have access to the Eurosystem via EFSF securities (€17 billion). Once an agreement has been reached between Greece and its creditors, Greek banks should once again have full access to the Eurosystem. Athens will need to reach an agreement quickly, because if the flight of deposits continues, the banking system will find itself in a real liquidity crisis. Time is running out…