Leasing (also known as finance leasing) has grown significantly in recent decades as a tool for financing assets. Although contracts corresponding to leasing practices have existed for centuries, analysis of their economic characteristics remains relatively sparse in the economic literature. This article first reviews the defining elements and a number of microeconomic reasons justifying the use of leasing by both lessors and lessees. Focusing on its penetration rate in investment financing, it shows that leasing appears to have experienced accelerated growth over the last two decades. An analysis of the types of assets most commonly leased in Europe reveals that vehicles constitute the largest segment of the corporate leasing market, far ahead of equipment and real estate. Finally, the note reviews a number of risks (interest rate increases, residual value risk, regulatory risk, geopolitical risk) that are likely to affect leasing operators in the current environment.

DISCLAIMER: The opinions expressed in this note are those of the author alone and do not represent those of BSI Economics or its employer.

Download the PDF: focus-on-leasing-between-boom-and-new-risks-note

The recent « social leasing » experiment launched by the French government to boost the adoption of electric vehicles has come to a surprising conclusion, to say the least. This unprecedented scheme offered long-term leasing of electric cars to low-income households at a monthly rental of just €100. Demand for this highly attractive offer quickly exceeded expectations, forcing the authorities to halt the scheme after six weeks to avoid a massive overspend of the allocated budget.

Beyond the somewhat comical aspect of this anecdotal fact, it also reveals the normalization of leasing within the automotive market. While it accounted for only 11% of financing for individuals purchasing new vehicles in 2012, leasing reached 47.2% in 2021. For businesses, the rate of leasing for vehicle financing already exceeds 80%. Moreover, the automotive sector is not the only one affected. Leasing now covers a wide range of assets, including industrial machinery, advanced medical equipment, IT and office equipment, shopping mall space, and even aircraft.

Despite the widespread presence of leasing in the economy and its long history in human societies[3], this method of financing remains relatively under-discussed in legal and economic literature, as noted by T. Merrill (2020)[4]. This note will therefore seek to provide some qualitative and empirical insights into the economic motivations behind the use of leasing, its macroeconomic and sectoral dynamics over the last few decades, and the potential risks currently facing the industry.

A brief reminder of the definition of leasing and its terms and conditions is provided in the appendix for readers who are unfamiliar with the subject.

1. What economic reasons justify the existence of leasing?

From a microeconomic perspective, there are several reasons why agents prefer leasing to buying/selling. From the lessee’s point of view, the main arguments in favor of leasing are:

- The ability to overcome constraints on access to the resources needed to acquire assets.This argument is particularly relevant for SMEs or households that do not have large cash reserves or sufficient access to bank credit to finance a significant initial investment. By using leasing, companies can more easily acquire the assets they need for their activities (offices and furniture, vehicles, machinery, and equipment, etc.) while retaining part of their resources for other investments. A 2015 study conducted by Leaseurope and Oxford Economics already showed that SMEs using leasing had investment levels more than twice as high (+123%) as those that did not. For households, beyond housing, leasing can facilitate access to assets such as motor vehicles without tying up a large portion of their savings.

- Reducing uncertainty about the quality of the asset. In a famous 1970 article, American economist George Akerlof highlighted a market imperfection phenomenon known as « adverse selection. » This describes a situation of information asymmetry in which buyers have less information about the quality of the goods on offer than sellers. This situation leads to a mismatch between the price asked by sellers (higher) and the price tolerated by buyers (lower to compensate for the risk of purchasing a poor-quality good), paradoxically resulting in the gradual disappearance of good-quality goods from the market. The example used by Akerlof in his article was the used car market. Using this example, we can see that leasing can partially solve this problem. By offering buyers a lease, sellers give them the opportunity to test the actual quality of the vehicle for a defined period before making their final decision on whether or not to buy the car, limiting the risk for the buyer and the adverse selection problem mentioned above.

- Avoiding the transaction costs associated with maintaining and disposing of an asset. Taking full ownership of an asset also means having to consider how to maintain it and dispose of it. Some assets will be resold, requiring a detailed analysis of their residual value. Others will have to be disposed of or recycled. The use of operating leases[6] allows a lessee with little experience in these operations to avoid complex and costly procedures by leaving them to the discretion of the lessor, who, through economies of scale and learning effects, is better able to manage these issues and the associated risks.

From the lessor’s point of view, the main arguments justifying the use of leasing are:

- The guarantee of a stable income over time. The lessor isremunerated in the form of regular rent paid by the lessee. Lessors with a certain aversion to risk may prefer this option to buying and selling, which is characterized by cyclical movements that are more difficult to anticipate.

- Greater security in the event of default by the counterparty. As shown by T. Merrill, the very structure of the leasing contract tends to facilitate the return of the asset to the lessor in the event of default by the lessee, compared to a creditor facing default by a borrower. Since leasing involves a transfer of ownership for a period « shorter than the expected useful life » of the asset, it is already understood that the lessor will ultimately regain ownership of the asset at the end of the contract. This provision allows the lessor to adjust the term of the lease according to the tenant’s level of risk (a tenant deemed risky will be given a shorter lease than a low-risk tenant). For the creditor, the task is more complex because the borrower is now, in theory, the full owner of the asset. The creditor will then have to obtain a court order confirming default of payment and authorizing the forced sale of the asset, a process that is often lengthy and fraught with pitfalls.

2. Analyzing leasing dynamics in the data

Although increasingly accessible, public data on leasing practices remains scattered and poorly consolidated. Nevertheless, it is possible to draw on figures published by the Solifi Global Leasing Report, which aggregates international data on lease financing of corporate investment activities. The 2024 edition of the report includes a « leasing penetration » indicator calculated as the total amount of leasing expenditure in a given year in a country divided by the total investment expenditure (excluding real estate) observed in that same country.

Looking first at the unweighted average of the countries studied, it is possible to discern an upward trend in the leasing penetration rate over the period studied, with the average rate rising from 10%–15% in the 2000s to 20%–25% in the 2010s and to nearly 30% in 2022. It is striking to note that the acceleration in the penetration rate has been particularly marked over the last two years in continental European countries (France, Germany, Italy) as well as in the United Kingdom and Sweden. Much of this sharp increase appears to be closely linked to the dynamism of the car leasing market, particularly for electric vehicles, encouraged by generous government subsidies.

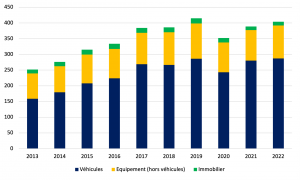

The figures published at European level by Leaseurope allow us to see a little more clearly by separating the annual value of leasing transactions into three main groups: (i) vehicle leasing (private and commercial vehicles combined), (ii) equipment leasing to businesses excluding vehicles (machinery and other industrial equipment, IT and office equipment, etc.), and (iii) real estate leasing. Figure 3 below shows this breakdown by asset.

It is interesting to note that annual leasing transaction amounts in Europe grew steadily over the period 2013-2019 before coming to a halt with the onset of the pandemic. The level of activity forecast for 2022 also indicates that, despite an undeniable rebound, the volume of transactions will remain below that observed in 2019. Motor vehicle leasing clearly dominates the European market and has even tended to increase over time. While leasing for this type of asset accounted for 63% of the total market in 2013, it accounted for 71% of the annual value of transactions in 2022. It should be noted that neither non-vehicle equipment (26% in 2022) nor real estate (3%) returned to their 2019 transaction levels following the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. Without jumping to conclusions, it is reasonable to assume that the disruptions to business models (e.g., teleworking) played a role in the sluggish recovery of these two types of assets.

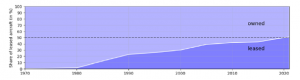

Beyond the three major categories mentioned above, another asset that has been particularly affected by the rise of leasing, this time on an international scale, is air transport equipment. As shown in Figure 4 below, the share of aircraft leased by scheduled and low-cost airlines combined has increased significantly since the 1980s, reaching 50% after the Covid-19 pandemic.

Figure 3: Annual value breakdown of leasing transactions in Europe, by asset (€ billion)

Source: Leaseurope

Beyond the three major categories mentioned above, there is another asset that has been particularly affected by the boom in leasing, this time on an international scale: air transport equipment. As shown in Figure 4 below, the proportion of aircraft leased by scheduled and low-cost airlines combined has increased significantly since the 1980s, reaching 50% after the Covid-19 pandemic.

This rise in leasing in the air transport sector has largely paralleled the growth in demand for this type of service over the last 50 years, as well as the deregulation of the sector since the late 1970s. With airlines needing to ramp up quickly to meet this new demand while optimizing their capital costs in an increasingly competitive environment, they have increasingly turned to leasing because of the flexibility it offers as a means of acquiring assets.

Figure 4: Global share of aircraft leased by airlines

Source: Wandelt, Sun, and Zhang (2023)

- The leasing industry faces new risks

Although the above analysis tends to show growth in leasing activities over the past two decades, it is also important to note that lessors are currently facing new forms of risk in a constantly changing environment.

The financial fragility caused by rising interest rates is a major challenge. To address the inflationary crisis that began in 2021 due to the strong post-COVID recovery in demand, and intensified by the economic consequences of the war in Ukraine, central banks have embarked on a rapid and substantial rise in their key interest rates. This monetary tightening has directly affected the leasing market through an increase in the cost of financing assets. In response, lessors have increased the rent charged to their tenants, but their room for maneuver is not infinite, particularly in view of the prospect of weak economic activity in 2024. The anticipated decline in key interest rates during the year should nevertheless halt this upward trend in financing costs, without however eliminating the problem of lessors’ debt.

This monetary tightening also creates a risk of loss on residual value in a context of disinflation. To understand the mechanism, we must first briefly explain how a lessor can incur a loss on the residual value of an asset. When signing a leasing contract with a lessee, the lessor will provide an estimate of the price at which it expects to be able to resell the asset at the end of the contract. This estimate will itself affect the level of rent charged to the lessee, which will be lower if the estimated residual value is high and vice versa. If this estimate ultimately proves to be higher than the actual resale price, the lessor will incur a loss in its financial results. In the current environment, it is therefore understandable that the risk of loss on residual value is a corollary of the interest rate risk mentioned above. While the price of many assets has risen sharply in recent years, with considerable uncertainty about the duration and magnitude of inflationary pressures, the risk of misestimating residual value was particularly high. Restrictive monetary and financial conditions and downward pressure on the prices of certain assets (real estate being a good example) could lead to sharp corrections in anticipated residual values and have significant consequences for the financial margins of certain lessors. It should be noted that in the case of finance leases, the loss on residual value can be similar to a loss on collateral.

Regulatory risk is also taking on new importance in the context of the ecological transition. Like other players in the economy, leasing companies are increasingly being encouraged by regulatory authorities to accelerate the process of greening their assets. One example is the automotive sector in France, with the Mobility Orientation Law (LOM). The LOM law stipulates that a certain percentage of the existing fleet must be replaced with low-emission vehicles (<50gCO2/km). This percentage will be increased periodically according to a schedule set by the legislation. The current version of the law is not binding on rental companies as it does not include a penalty mechanism. However, this could change. A proposal submitted by MP D. Adam at the end of January 2024 aims to (i) raise the intermediate thresholds for fleet renewal by rental companies and (ii) impose a system of fines of up to 1% of French turnover and restricted access to public procurement contracts[14]. Rental companies, which until now have been highly specialized in combustion-engine vehicles and financially constrained, could find themselves in difficulty in the face of new regulatory requirements aimed at accelerating the greening of the sector’s practices.

Finally, for the largest players, there is the geopolitical risk of unexpected asset seizures. In an increasingly fragmented and unstable world, leasing companies could become collateral victims of a potential international conflict, with their assets illegally seized by one of the belligerents. The largest air transport equipment lessors (AerCap, Carlyle, etc.) recently suffered the consequences of this following the outbreak of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In response to European and American sanctions aimed at weakening its national aviation industry, Russia seized nearly 400 aircraft leased from Western leasing operators, causing heavy financial losses for the latter[15].

The industry’s ability to cope with these new risks will be key to maintaining its growth momentum in the coming years. This would be desirable given leasing’s ability to offer a credible alternative to full ownership and to provide greater flexibility to players in many sectors of activity.

Appendix

What is leasing?

In his 2020 article, T. Merrill defines leasing as « a transfer of possession and use of a physical asset for a period shorter than its expected useful life, in exchange for economic consideration. »

A thorough analysis of this definition also makes it possible to distinguish between transactions that qualify as leasing and those that do not:

- Leasing differs in particular from very short-term rentals (e.g., Airbnb rentals), which do not strictly speaking involve a transfer of possession from the lessor to the lessee, who is considered in this type of rental to be merely a « guest. »

- Nor is it possible to associate leasing with a simple « deposit » (a somewhat crude French translation of the English term » bailment » ), whereby the person receiving the transferred property has it at their disposal only for a specific, non-discretionary use. An example would be a mechanic taking possession of a customer’s car for a few days or weeks for the sole purpose of repairing it and not using it for his own needs.

- The concept of « physical assets » effectively excludes software licenses and other intangible assets.

- Gifts or donations, for a period shorter than the useful life of the transferred asset, without any expectation of compensation from the beneficiary, cannot be considered leasing. Leasing must always have a commercial purpose.

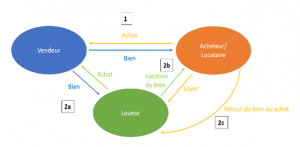

Figure 1: Comparison between purchase and leasing

Source: author

Let’s add to this a further distinction between « operational » leasing and « financial » leasing. Financial leasing refers to a type of transaction in which the lessee obtains ownership of the asset upon signing the contract and subsequent payments to the lessor are accounted for in a similar way to a loan. Conversely, operating leases do not involve a transfer of ownership between the lessor and the lessee, but only a right of use. The rent paid is similar to a payment made in exchange for the right to use the asset for the duration of the contract. It should be noted that, since 2016, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) requires both finance and operating lease transactions to be recorded on companies’ balance sheets. This was not previously the case for operating lease contracts.

To better understand how a leasing transaction works and how it differs from a traditional purchase, a simplified graphic representation may be useful (see Figure 1 above). In a traditional purchase (represented by transaction 1), a seller and a buyer enter into a bilateral transaction in which the buyer obtains full ownership of an asset previously owned by the seller in exchange for a sum of money that may be paid in one or more installments.

In a leasing transaction, the lessor first acquires the asset from the seller through a conventional purchase (2a) before leasing the same asset to the lessee (with an option to purchase at the end of the contract) for a fixed term shorter than the useful life of the asset in exchange for periodic rent payments (2b). The manner in which the lessor acquires the asset from the seller can vary greatly depending on the type(s) of resources mobilized (equity, cash, debt) and the choice of a method of direct ownership of the asset (recorded on the lessor’s balance sheet) or indirect ownership (through a special purpose vehicle, for example). At the end of the lease term, the lessee may decide to return the asset to the lessor or exercise its purchase option, allowing it to acquire full ownership of the asset in exchange for payment (2c).

[1] Guillaume Gichard, « Electric cars: the executive puts an end to social leasing for 2024, » Les Echos, February 12, 2024.

[2] Anne Feitz, « The great leap forward in car leasing, » Les Echos, January 3, 2022.

[3] Frier (1980), for example, highlighted the existence of agricultural land leases as far back as the Roman Empire.

[4] Thomas W. Merrill, The Economics of Leasing, 12 J. of Legal Analysis 221 (2020).

[5] George A. Akerlof, The Market for “Lemons”: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism,The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 84, Issue 3, August 1970, Pages 488–500.

[6] See the distinction between operating and finance leases in the appendix.

[7] Assilea, Annual Leasing Report 2023-2022.

[8] Sebastian Wandelt, Xiaoqian Sun, Anming Zhang, Is the aircraft leasing industry on the way to a perfect storm? Finding answers through a literature review and a discussion of challenges, Journal of Air Transport Management, Volume 111, 2023.

[9] Sebastian Wandelt, Xiaoqian Sun, Anming Zhang, Is the aircraft leasing industry on the way to a perfect storm? Finding answers through a literature review and a discussion of challenges, Journal of Air Transport Management, Volume 111, 2023.

[10] The United States led the way with the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 signed by President Jimmy Carter. Two decades later, in 1997, the European Union completed the deregulation of its own airspace (Fayolle, 20003).

[11] Between July 2022 and September 2023, the European Central Bank raised its main refinancing operations interest rate by 450 basis points, reaching a level not seen since the early 2000s. For its part, the Fed raised its key interest rate by 525 basis points between February 2022 and July 2023.

[12] One notable example is the automotive industry.

[13] The percentage of the fleet requiring renewal has been set at 20% since January1, 2024, and will increase to 40% in 2027 and then 70% in 2027.

[14] Bill No. 2126 registered on January 30, 2024, National Assembly.

[15] Bruno Trévidic, « Moscow confiscates $10 billion worth of aircraft leased to Westerners, » Les Échos, March 14, 2022.