Summary:

– Emerging economies have been experiencing turbulent times since the beginning of the summer. Their financial indicators (exchange rates, stock market indices, etc.) have seen their sharpest decline since the 2008 crisis.

– This is a sharp reaction by the markets to the likely slowdown in the Fed’s quantitative easing program between now and the end of the year.

– But this reversal in confidence in emerging economies is also the result of the accumulation of macroeconomic fragilities in these countries.

– This sudden rise in financial tensions will not be without consequences for emerging economies, whose monetary policy must adapt quickly.

The summer of 2013 saw a rise in financial tensions in emerging economies

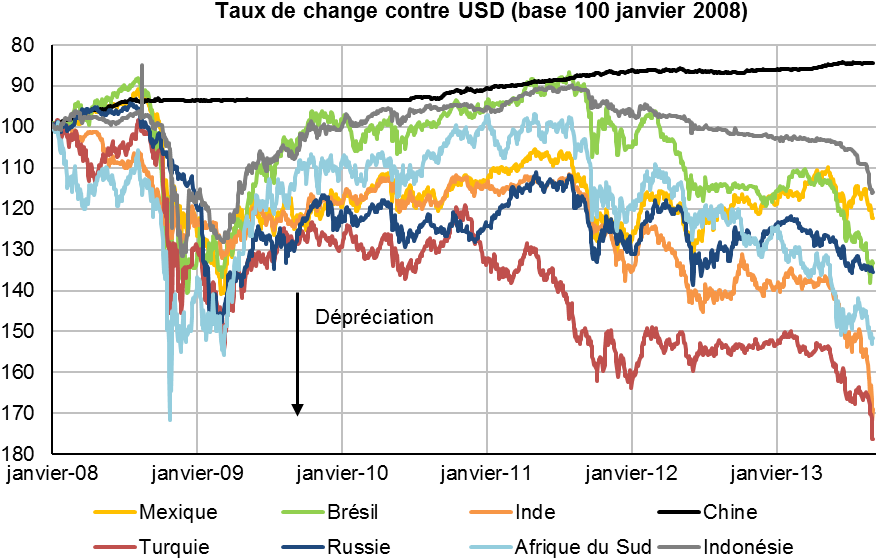

Since the end of May, emerging economies have been experiencing a very turbulent period financially. Admittedly, this is not the first time since the cataclysm that shook the global economy and financial system in the fall of 2008 that turbulence has been felt in the « tropical » financial markets, from Rio to Jakarta. The post-crisis rebound, which began in 2010 and was accompanied by a trend toward appreciation of emerging market currencies and assets, has not been smooth sailing. Already in September 2011 and May 2012, markets had trembled, unsettled by uncertainties in the euro zone.

Sources: Macrobond, BS-Initiative

But this summer’s episode, in terms of its scale and duration, stands out from previous ones. In September 2011, the currencies of the main emerging economies [1] lost only 9% on average; in May 2012, 5%. Between early May and late August 2013, the same currencies fell by nearly 15%. The Indian rupee was hardest hit, losing 17% of its value betweenMay 1and August 31. It was followed by the Brazilian real (-13%), the South African rand (-8%), the Turkish lira (-10%), and the Indonesian rupiah (-11%). As a result of a sharp reversal in capital inflows (net monthly capital inflows to emerging economies are estimated to have fallen by tens of billions of dollars since June), this movement was accompanied by a parallel deterioration in financial indicators: stock market indices lost an average of 23% between early May and late August, and sovereign spreadswidened significantly (see table).

Sources: Macrobond, BS-Initiative

The likely slowdown in quantitative easing between now and the end of 2013 was the trigger for these tensions…

To understand where these tensions came from, it is necessary to look closely at the timing of the statements made by the Fed and its Chairman Ben Bernanke. On May 22, during a hearing before Congress, Bernanke suggested for the first time that the Fed’s Treasury bond purchase program—the famous quantitative easing —could slow down by the end of the year [2]. This is not a tightening of monetary policy, but a possible « lessening of easing » (conditional on a recovery in activity across the Atlantic). However, it was enough to trigger a wave of panic in emerging financial markets. Since this initial statement, market operators have been analyzing statements by Fed governors and scrutinizing US economic indicators, looking for any hint or sign of recovery that would confirm Bernanke’s statements. In mid-August, positive macroeconomic data (particularly on unemployment and inflation) was published in the United States, reigniting tensions in emerging markets.

… reminding anyone who may have forgotten of the macroeconomic fragilities in emerging economies

While it seems clear that the trigger for the tensions lies across the Atlantic, how can we explain why not all emerging economies have been affected as severely? Specific macroeconomic weaknesses, long forgotten or even neglected, have « returned » to the forefront.

For the past two years, the major emerging economies have been slowing down, raising doubts about the sustainability of their growth model. They have high current account deficits, often financed by short-term capital. In addition, they are struggling to control inflation, which often flirts with the central bank’s target. The economies most affected (India, Brazil, Turkey, South Africa, Indonesia) all share these vulnerabilities to varying degrees (see charts below). India is a case in point. After double-digit growth rates in the 2000s, India is struggling to reach 5% (3.8% in 2012 and 4.6% in the first half of 2013). The current account deficit has deteriorated every year since 2009, reaching 5.1% of GDP in 2012. Finally, inflation peaked at nearly 11% last February. To borrow a well-known expression, one could say that « shining India » has given way to « sluggish India. » At least, that seems to be the view of the markets…

Sources: IMF / Macrobond / BS-Initiative

What are the consequences for emerging economies and what solutions are available to the authorities?

This resurgence of financial tensions has a direct impact on emerging economies. For those most affected, the depreciation of the exchange rate has increased the price of imports and generated imported inflation. This is particularly the case in Turkey and India. The central banks of the most affected countries have therefore embarked on a general trend of raising key interest rates to discourage capital outflows and limit credit growth. While this could effectively limit price increases, the effect on economic activity is likely to be felt quickly, through higher borrowing costs that will impact consumption and investment. The IMF’s next growth forecasts, to be published in next month’s World Economic Outlook, will undoubtedly be revised sharply downward from those of July. Finally, can we expect a rebalancing of the external accounts of countries with current account deficits? The effect of depreciation on the trade balance is ambiguous and depends primarily on the elasticity of exports and imports in relation to prices. While the gain in price competitiveness should enable some countries to boost their exports (particularly those that were penalized by an overvalued exchange rate: Brazil, Turkey, South Africa), the energy bill is likely to increase significantly for major oil importers (India, Turkey).

In addition to the monetary tightening they have embarked upon, the central banks of emerging economies are intervening in the foreign exchange markets, drawing on their foreign exchange reserves accumulated since the early 2000s. While it is difficult to assess precisely the volumes involved, they certainly exceed $100 billion. In the case of Brazil, these interventions appear to have stemmed the bleeding. But this may not be enough if tensions continue.

***

Just over three months after the outbreak of financial tensions in emerging economies, and with these tensions likely to intensify again when the Fed’s monetary policy committee minutes are published in mid-September, what lessons can we already learn? While the market reaction was excessive and destabilizing, it brought the fragility of emerging economies back to the forefront. This is a warning to current leaders, reminding them of the need to implement long-term reforms, which alone will generate strong, balanced growth and reduce vulnerability to the international economic climate. With 2014 being an election year in several countries (India, Turkey, Indonesia, Brazil, South Africa), there is no doubt that governments will make the right decisions. The question remains whether these decisions will be good for them or for their countries…

Notes:

[1] BRIC + South Africa + Indonesia + Turkey

[2] For more details on the Fed’s successive programs since the crisis, see Julien Moussavi’s article published on our website.