DISCLAIMER: The opinions expressed by the author are personal and do not reflect those of the institution that employs her.

Summary:

- The slowdown in the Chinese economy and its structural imbalances (the economy’s dependence on investment and exports) raise questions, while financial (private debt, decline in the real estate sector) and social risks are gradually emerging.

- To address these issues, the authorities now want to embark on a new phase of development and rely on new growth drivers based on a strategy known as « common prosperity. »

- The concept of « shared prosperity » would correct these imbalances and further support domestic consumption by reforming the wealth distribution system and strengthening social protection. It would also help reduce inequalities and maintain social stability.

- However, the authorities will have to accept less dynamic growth. Severe crackdowns on key sectors to combat speculation could also destabilize the economy and undermine household and business confidence.

Announced in 2021 at the Central Committee for Economic and Financial Affairs (CCEF) and reaffirmed at the Communist Party National Congress in October 2022, common prosperity is a flagship measure to change the economic development model of Xi Jinping’s administration. It complements the « dual circulation » strategy introduced in May 2020, which involves shifting the economic model away from exports and focusing more on developing the domestic market to meet the needs of the Chinese market.

The « common prosperity » strategy serves two objectives, both economic and social. It would stimulate domestic consumption by expanding the middle class while improving the income distribution and social protection systems. These reforms would stimulate private consumption and reduce the economy’s dependence on bank credit-driven investment. In addition, they would offer a possible solution to mitigate the financial risks associated with debt.

This article aims to explain why China is seeking to change its economic development model by relying on the « common prosperity » strategy and what its main objectives are.

1. An economy running out of steam

1.1 Declining structural growth

After years of exceptional performance until the mid-2010s, China is experiencing a sharp economic slowdown, with pre-pandemic average growth of +7%. In 2022, it is expected to miss its growth target of +5.5% set at the beginning of the year. While the slowdown is partly attributable to the evolution and management of the health crisis and a slowdown in global demand, it also has significant structural causes.

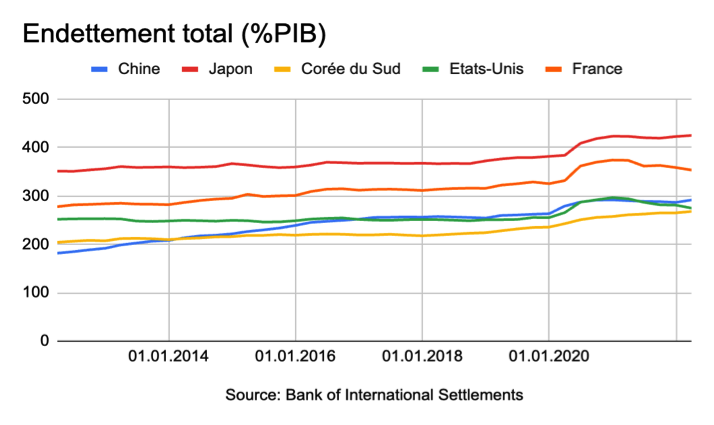

The acceleration of demographic decline (aging population and historically low birth rates) and the economic slowdown linked to the coronavirus crisis are reminding China of the consequences of excessive private debt. The authorities recognize that private debt is no longer sustainable (200% of GDP) and have therefore accelerated « crackdown » measures in 2021, most of which fall under the banner of « common prosperity, » in order to correct social inequalities, balance growth, and ensure financial stability.

1.2 Regulatory tightening reveals the difficulty of relying on traditional growth drivers

However, early signs in the real estate industry are showing the limits of common prosperity. The regulatory tightening implemented to control the expansion of private debt, although necessary, has caused a liquidity crisis in real estate, a sector that accounts for nearly one-third of GDP. Indeed, by implementing the Three Red Lines[1], the conditions for accessing financing for real estate projects have caused liquidity stress among real estate developers and a series of defaults (such as those observed with Evergrande, Kaisa, and Shimao at the end of 2021). With access to financing more limited, indebted developers were forced to suspend real estate projects, most of which had been pre-sold.

The real estate crisis then severely damaged household confidence. Many of them stopped repaying their loans in protest, affecting nearly 340 real estate projects in September 2022. Demand has also been weak, with real estate prices and transaction volumes contracting since May, despite the support measures announced, such as the $147 billion fund to help real estate developers complete ongoing projects.

By targeting the real estate sector, the authorities are in fact attacking a growth engine that has often been used in the past to restart growth by stimulating credit growth. It would appear that only fiscal and monetary support measures could stimulate growth in the short term.

1.3 Limited room for maneuver in the short term to boost growth

Although the authorities have signaled their willingness to stabilize the economy in 2022, in reality, the room for maneuver appears to be quite limited. Rising interest rates in the United States are increasing pressure on capital outflows from China. Nevertheless, the Chinese monetary authorities have conceded several interest rate cuts in 2022, favoring short-term support for economic activity rather than actually seeking to smooth the decline of the renminbi[2]. The reduction in 1-year and 5-year borrowing rates by 5 basis points last August, to 3.65% and 4.3% respectively, has not succeeded in reviving domestic consumption or the real estate market.

Fiscal policy has been used more cautiously to support economic activity in order to avoid increasing local government debt too sharply. Indeed, the IMF’s increased debt, including local and central government debt and off-budget debt (such as local government financing vehicles), deteriorated between 2019 and 2021, rising by 20 points of GDP to 101% of GDP. Most of the public debt is borne by local governments in order to keep central government debt low (21% of GDP in 2021). However, lockdowns, increased health spending (mass COVID testing), tax cuts, and falling real estate prices[3] have severely deteriorated the financial situation of local governments.

2. The debt-driven economic model: a catalyst for financial and social risks

2.1 A necessary rebalancing to reduce the risks associated with endemic debt

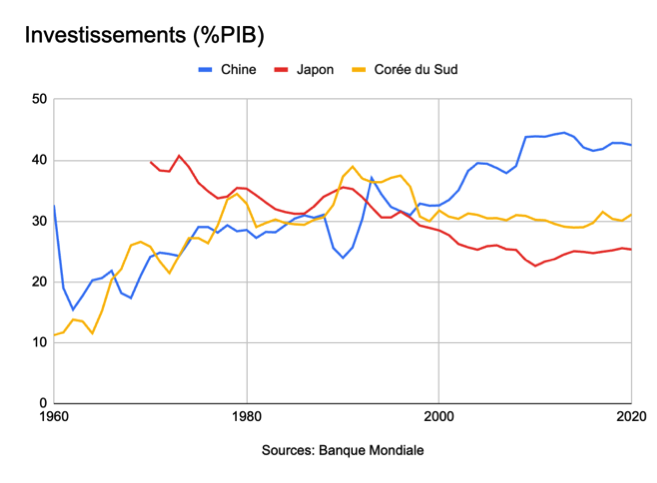

The imbalance in the structure of the Chinese economy dates back to the early 2000s. The boom in exports enabled the economy to record significant trade surpluses, peaking at 9% of GDP in 2017. At the same time, investment as a share of GDP also became significant, averaging 36% of GDP in the early 2000s, supported by the development of manufacturing and infrastructure to meet growing demand for housing. At the onset of the 2008-2009 global financial crisis, investment accounted for nearly 40% of GDP, exceeding the levels seen in Japan and South Korea during their periods of strong growth prior to the Asian crisis. Today, it stands at around 42% of GDP, while private consumption has stagnated at 37% of GDP since 2016.

This imbalance widened significantly during the 2008 financial crisis. To respond to insufficient external demand (a 20% drop in exports in 2009) and falling corporate profits, a massive stimulus package worth around 12% of GDP, driven by infrastructure investment, was put in place to maintain the growth target of +8%. However, the increase in investment was quickly accompanied by a substantial rise in corporate and household debt, particularly through mortgages linked to the development of the real estate sector. In fact, policies encouraged household borrowing in order to transfer the flow of credit from zombie companies to households in 2015. In addition, real estate prices rose sharply from 2016 onwards (by 10% on average), a phenomenon that was accompanied by a rapid increase in household debt (from 28% of GDP in 2012 to 61% in early 2022).

2.2 A rebalancing to address inequalities and support domestic consumption

The concept of « common prosperity » partly echoes former President Deng Xiaoping’s vision of a « moderately prosperous society, » a goal that would have been achieved in 2021 with the announcement of the eradication of absolute poverty. However, Deng’s philosophy that « some can get rich first » has enabled China to enjoy rapid growth but has also been accompanied by an increase in income and wealth inequality.

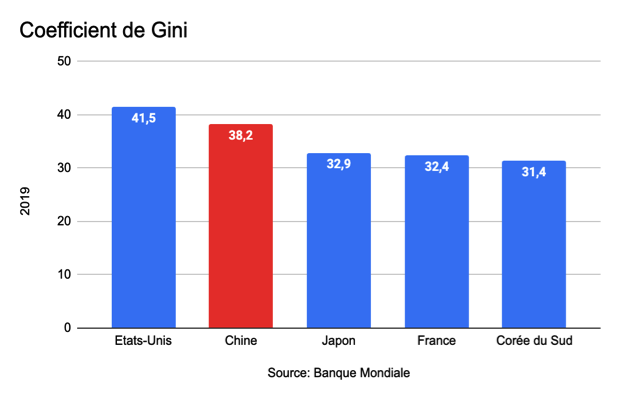

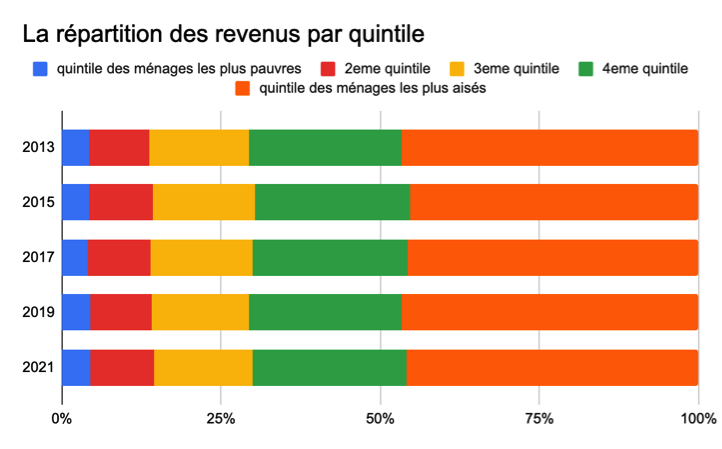

Indeed, the Gini coefficient, which measures the degree of inequality within the population, remains high compared to that of developed economies. According to World Bank figures, China’s coefficient, although it has fallen by 5 points in ten years, stands at 38 in 2019 compared to 31 in Korea and 32 in Japan and France (100 reflecting perfect inequality). Income figures by quintile from the National Bureau of Statistics also show a concentration of wealth in the top quintile, even though income distribution has remained relatively unchanged over the past ten years.

Despite concerns about income inequality, China’s tax system has been uneven and penalizes the middle class more than the wealthy. Most of China’s tax revenue comes from VAT and social security contributions, which place a heavier burden on the middle class and the poorest. Furthermore, China does not collect taxes on capital gains, inheritance, or private property. In fact, China is one of the few countries in the world that exempts households from property tax, relying instead on revenue from public land leases.

We should therefore expect reforms to the tax system as part of the pursuit of shared prosperity. In his opening speech to the Congress, Xi emphasized his commitment to regulating the system of wealth accumulation. Given the tax structure, the introduction of property tax and inheritance tax could be considered by the authorities in the future, targeting the wealthiest. However, plans to introduce property tax have been postponed due to the current crisis in the real estate sector.

Tax structure in Asia (% of GDP)

Source: OECD, Revenue Statistics, BSI Economics

Finally, better social security coverage could reduce households’ precautionary savings and boost consumption. China’s transition from a planned economy to a market economy has been accompanied by a transformation of social security coverage, which remains weak. Public spending on social protection is still far below that of developed countries—China spends 7% of GDP compared to 18% in Japan, for example. The lack of social safety nets has encouraged households to build up precautionary savings, which are among the highest in the world (44% of GDP compared to a global average of 28%).

Furthermore, the National Urbanization Plan (2014-2020) launched in 2014 has failed to reform the hukou system. Adopted by China in the 1950s, the hukou system divides all citizens into two subsystems: one for urban residents and another for rural residents. However, most low-cost urban workers do not have registration certificates, which prevents them from accessing basic social benefits, such as public education for their children, forcing migrant parents to leave their children in the village and creating tens of millions of separated families. One of the main objectives of the hukou reforms was to modestly close the gap or deficit in urban social benefits by two percentage points by 2020, i.e., from 17.3% in 2012 to 15% in 2020. However, the data show that this target has not been met. On the contrary, the social benefits deficit has widened, reaching 26.6% in 2020 according to the KNOMAD organization, which tracks migration, which is higher than the 15% target set in 2014.

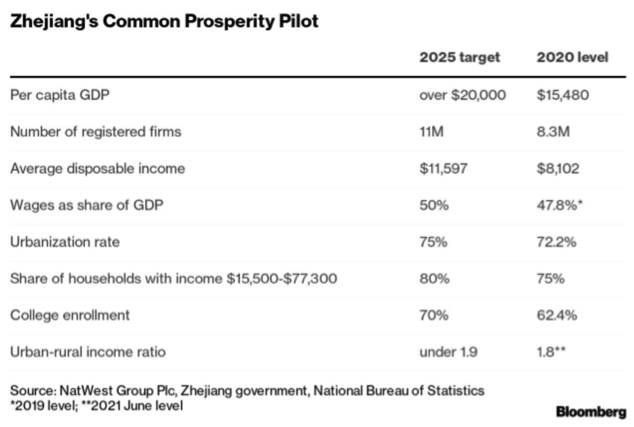

In practice, the authorities have already launched a pilot program since June 2021 in Zhejiang, considered the « cornerstone » of shared prosperity, by accelerating the urbanization and technological transformation of its manufacturing areas. The province aims to accelerate the urbanization rate from 72% in 2020 to 75% by 2025, supported by government investment in infrastructure.

Source: NBS, Bloomberg

Conclusion

China’s economic shift is now vital to achieving more balanced and therefore more sustainable growth, with private consumption at the heart of the economic model.

While Common Prosperity is the desired path, as the authorities reiterated at the 20th Communist Party Congress, it could nevertheless prove risky in the short term if the authorities lose domestic confidence through measures deemed severe, in an external environment that is becoming less favorable to China.

Sources

China’s economic growth and rebalancing and the implications for the global and euro area economies, ECB, 2017

How inequality is undermining China’s prosperity, CSIS, 2022

CPC Future, The New Era of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics, Frank N. PIeje and Bert Holman, editors 2022

Revenue Statistics in Asia and the Pacific 2022: Strengthening Tax Revenues in Developing Asia, OECD, 2022

Xi’s vow to regulate wealth spurs calls for taxing the rich, Bloomberg, Oct. 2022

Rebalancing Act: China’s 2022 Outlook, Jan. 2022 and updated June 2022, World Bank

China’s Shift to Consumption-Led Growth Can Aid Green Goals, Jan. 2022, IMF

[1] The Three Red Lines: financial soundness criteria that real estate developers must meet in order to borrow more. These criteria include an asset-to-liability ratio of less than 70% and a net debt ratio of less than 100%.

[2] The Central Bank has nevertheless lowered the ratio of mandatory foreign currency reserves for banks in an attempt to prevent a more sharp fall in the renminbi.

[3] Land sales, via usage rights, constitute a very significant portion of local government revenues.

[4] Zombie companies: the Chinese State Council defines « zombies » as companies that have suffered three years of losses, are unable to meet environmental and technological standards, do not align with national industrial policies, and rely heavily on government or bank support to survive. An expansionary policy has encouraged investment in unprofitable industries.

[5] However, a plan to create a harmonized property tax across the country has been under discussion for several months, with the aim of supporting local government finances. The real estate crisis is likely to delay such a plan.