Summary:

- For a long time, the European Central Bank’s (ECB) monetary policy was based on steering the overnight interbank market rate (EONIA), which was kept at the center of a rate corridor, close to the main refinancing operations rate (REFI rate).

- The massive injections of liquidity implemented since 2008 have profoundly changed this framework, leading to a sustained abundance of liquidity and a convergence of money market rates towards the deposit facility rate.

- In this context, the REFI rate has gradually lost its central role in operational implementation, while the deposit facility rate has become the main anchor for money market conditions.

- The ECB’s review of the operational framework in 2024 does not aim to return to the pre-2008 regime, but rather to adopt an intermediate framework based on ample liquidity, building on what is sometimes described as a structural change in banks’ liquidity demand.

- This new framework is based on a diversification of liquidity-providing instruments, a narrowing of the interest rate corridor, and the continuation of fixed-rate tenders with full allotment.

Download the PDF: how-the-ecb-implements-its-monetary-policy-yesterday-today-and-tomorrow.pdf

Monetary policy is omnipresent in economic debates. Anyone interested in economics knows that modern central banks seek to control interest rates in the economy, which in turn influence a wide range of financial and macroeconomic variables, impacting economic behavior and, ultimately, activity and inflation.

However, how central banks actually set their own interest rates often remains less well known. Bundesbank President Joachim Nagel recently pointed out that the field of monetary policy implementation is « mainly uninhabited by economists » (Nagel, 2024).

Yet this field has undergone profound changes over the past 15 years, changes that crystallized with the European Central Bank’s (ECB) announcements in 2024 regarding its future operational framework. This article offers a journey into this relatively unexplored territory, looking back at the implementation of monetary policy in the euro area over the past two decades before discussing the approaches chosen for the years to come.

The pre-2008 regime

Originally, the ECB’s mission was clear: to set interest rates in order to ensure price stability. The ECB only directly controls the rates it administers itself. There are three such rates, which can be ranked from lowest to highest: the deposit facility rate, the main refinancing operations rate (REFI rate), and the marginal lending facility rate.

Historically, these three rates were used to control the overnight interest rate on the interbank market, the EONIA (which disappeared in 2022). EONIA was the name given to the average rate at which eurozone banks lend each other liquidity, on an unsecured basis, for a period of one day.

How did the central bank manage to influence this rate? The answer lies in the relationship between these three administered rates and refinancing operations. We have already discussed this mechanism in a previous post (see this article by BSi Economics). Let’s first take a look at the three rates:

- The deposit facility rate is the rate at which banks can deposit their cash with the central bank for one day. It is currently the lowest rate in the corridor.

- The REFI rate is the rate at which the ECB provides liquidity in its weekly refinancing operations. Each week, banks know that they can borrow liquidity at this rate against collateral. Originally, these operations involved a predetermined amount of liquidity (decided by the central bank), allocated among banks via an auction mechanism.

- The marginal lending facility rate is the rate at which a bank can borrow liquidity from the ECB at the end of the day if it faces a cash shortfall and is unable to obtain financing on more favorable terms on the interbank market. This is the highest rate used by the ECB.

These three rates formed a corridor system that provided a framework for the interbank rate. The deposit facility rate set a floor for the corridor: no bank had any incentive to lend to another bank at a rate lower than the rate it could obtain by leaving its money in the ECB’s deposit facility. The marginal lending facility rate set a ceiling: no bank had any interest in borrowing from another bank at a rate higher than that offered by the central bank.

Between these two limits, the ECB adjusted the supply of liquidity during its weekly refinancing operations and set, via the REFI rate, the price at which it refinanced banks, so that the interbank rate would settle close to this rate. Intuitively, the central bank sought to anticipate banks’ demand for liquidity and to provide a quantity such that the market equilibrium would be around this rate (this intuition is a simplification; see Borio and Disyatat (2009) for a more complete analysis).

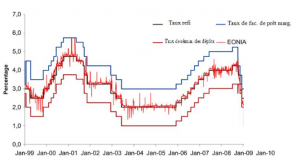

As can be seen in the first part of Figure 1, this framework allowed the ECB to closely control the EONIA, with only a few episodes of volatility (see this article by BSI Economics).

Chart 1: EONIA and key interest rates before 2008 (source: Reuters)

The break in 2008

This framework was profoundly disrupted by the 2008 financial crisis. Faced with financial tensions, central banks injected massive amounts of liquidity to stabilize the financial system. These policies were not quickly normalized; on the contrary, new programs were added over the years.

In 2011 and 2012, the ECB conducted two exceptional long-term refinancing operations (LTROs), each worth around €500 billion. These operations alone injected nearly €1 trillion in liquidity, or about six times the level of bank liquidity observed before the crisis (see this link: Consolidated balance sheet 2005).

From 2015 onwards, the ECB’s Quantitative Easing program (sovereign asset purchase program) reinforced this dynamic. In 2020, even though many were anticipating a gradual normalization, the COVID-19 crisis led to further injections via the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP) and other measures.

These policies led to a massive increase in the supply of liquidity on the interbank market. When the supply of liquidity becomes significantly greater than demand, the price of this liquidity, i.e., the interest rate, automatically falls. Interbank rates therefore moved closer to the lower bound of the corridor, i.e., the deposit facility rate. This can be seen in Chart 2 after 2008.

In this context of abundant liquidity, the REFI rate has gradually lost its role as the « main » rate. De facto, the deposit facility rate has become the ECB’s main operational rate.

Chart 2: EONIA and key interest rates before and after 2008 (source: FRED)

The change in the operational framework in 2024

Faced with this situation, the ECB had three main options:

- Wait for the balance sheet to return to its pre-2008 level in order to fully restore the traditional corridor system;

- Formalize a regime of abundant liquidity based explicitly on the deposit facility rate;

- Adopt an intermediate solution, characterized by a sufficient but not abundant level of liquidity, described as « ample. »

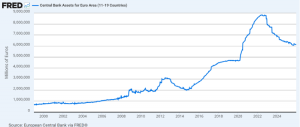

All three options appeared credible. Since 2022, the ECB’s balance sheet has indeed shrunk significantly, from around €9 trillion to nearly €6 trillion today (Chart 3), due to the repayment of long-term loans by banks and the non-renewal of maturing securities under the ECB’s Asset Purchase Program (APP) and Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP).

Chart 3: Evolution of the Eurosystem’s balance sheet (source: FRED)

Some officials, such as Bundesbank President Joachim Nagel, have argued for a significantly reduced balance sheet, highlighting the advantages of a framework that leaves more room for market mechanisms (Financial Times, 2023; Nagel, 2023). Others, on the contrary, have insisted on the need to maintain a structurally high level of reserves.

Indeed, a return to a framework that is exactly the same as the one that prevailed before 2008 raises questions about financial stability risks. The episode in the US repo market in September 2019 (see Les Echos, 2019) showed that, despite high reserves, liquidity problems could arise[1]. More broadly, this episode highlighted that banks’ demand for liquidity had changed profoundly (Copeland et al., 2021). In particular, the full implementation of the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR)[2] from 2017 in the United States gave bank reserves a « regulatory value » (ECB, 2025; Schnabel, 2025). This development contributed to an increase in banks’ demand for liquidity, at least as expressed in a regime of abundant liquidity (see Borio (2023)). Banks began to want to hold reserves[3] not only for operational purposes, but also to meet the liquidity requirements arising from the Basel III prudential framework.

Today, a significant portion of the high-quality liquid assets held by banks to meet their liquidity ratios (such as the LCR) consists of bank reserves (S&P Global Ratings, 2025). One of the main factors explaining this is the low opportunity cost of reserves, coupled with the fact that they are perceived as less risky than their main alternative, sovereign bonds, whose market value fluctuates. This context has led some observers to believe that demand for reserves can no longer be interpreted solely as a result of reserve requirements or payment needs, as was the case in the pre-2008 operating environment. The Banque de France, for example, points out that banks’ liquidity needs today are more driven by « regulatory and precautionary reasons » (Lez, 2024), which could justify the introduction of a generous reserve regime. Other economists, however, argue that this change in demand for reserves could be, to a large extent, endogenous to the operational framework itself and would therefore not, on its own, constitute a fully convincing justification for adopting a generous reserve regime[6].

It may therefore also be out of a desire for caution, and in order to ensure a gradual transition for banks in an uncertain environment, that the ECB decided, following its review of its operational framework in March 2024, to opt for what we refer to above as an « intermediate solution, » namely a framework based on ample reserves.

The future operational framework

So what will actually change in the ECB’s operational framework?

First, the ECB will no longer rely solely on weekly refinancing operations to provide liquidity. It also plans to use:

- Frequent long-term refinancing operations;

- A structural bond portfolio.

The aim is to ensure a structurally sufficient level of liquidity, while diversifying the instruments used to achieve this. The precise characteristics of these new tools have not yet been detailed by the ECB. Neither the maturity nor the frequency of the long-term refinancing operations has been specified, nor has the composition of the structural bond portfolio.

However, it is envisaged that this portfolio will consist mainly of short-term securities, which are considered more neutral[7] and allow greater flexibility in the event of future asset purchase programs. All of these elements should be clarified as the amount of liquidity in the market approaches the level considered « ample » by the ECB.

Another innovation (introduced in September 2024) is that the main refinancing operations rate (REFI rate) is now set at a level very close to the deposit facility rate, with a spread of only 15 basis points (bp). This is a significant decrease: the spread[8] between the two rates was previously 50 bps, and even 100 bps before 2008. The aim of this approach is to encourage banks to maintain regular bank reserves and limit volatility in the money market.

Refinancing operations continue to be conducted in the formof fixed-rate tenders with full allotment, which means that banks can obtain all the liquidity they request from the central bank at the announced rate, provided they have eligible collateral. This contrasts with the pre-2008 regime described above and transforms a mechanism that was initially designed to be temporary into a permanent feature of the operational framework.

Conclusion

Recent developments in the ECB’s operational framework illustrate how profoundly the implementation of monetary policy has changed since the global financial crisis.

Sustained liquidity abundance, the apparent transformation of reserve demand, and regulatory constraints have gradually shifted the center of gravity of monetary policy toward a regime based on ample reserves, giving greater importance to the floor rate. The 2024 review confirms this evolution for the coming years, even if its justifications and operational modalities remain imperfectly defined.

Julien PINTER

Bibliography

Borio, C. & Disyatat, P. (2009). Unconventional monetary policies: an appraisal. BIS Working Papers No. 292. Bank for International Settlements, Monetary and Economic Department, November 2009

Borio, C. (2023). Getting up from the floor (BIS Working Papers No. 1100). Bank for International Settlements

ECB (2025). The first year of the Eurosystem’s new operational framework, ECB Blog, April 25, 2025. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/blog/date/2025/html/ecb.blog20250425~fa1fb8e9ac.en.html

BSi Economics (2014) ECB negative interest rates: what are we talking about? https://bsi-economics.org/taux-negatif-de-la-bce-de-quoi-parle-t-on/

BSI Economics (2015). Why are there spikes in the EONIA at the end of each month? BSI Economics. https://bsi-economics.org/pourquoi-ces-pics-sur-leonia-a-la-fin-de-chaque-mois/

Financial Times (2023). ECB makes case for keeping balance sheet big. Financial Times.

Les Échos (2019). The Fed launches a fourth emergency financing operation. Les Échos.

Lez, P. (2024). Review of the ECB’s operational framework: why? How? Banque de France.

Nagel, J. (2023). Presentation of the Deutsche Bundesbank’s Annual Report 2023. Deutsche Bundesbank.

S&P Global Ratings (2025). Economic Research: Banks Call For Clarity On ECB’s Liquidity Tools After Quantitative Tightening Ends, S&P Global Ratings, 2025. Available at https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/regulatory/article/economic-research-banks-call-for-clarity-on-ecbs-liquidity-tools-after-quantitative-tightening-ends-s101644229

Schnabel, Isabel (2025). Towards a new Eurosystem balance sheet. BIS Review (speech, Basel, November 10, 2025). Bank for International Settlements. Available at https://www.bis.org/review/r251110n.pdf

[1] In September 2019, the US repo market experienced severe tensions, with overnight rates rising sharply, which took the vast majority of observers by surprise. This episode occurred during a week marked by two events affecting bank liquidity: a significant tax deadline for companies and a large issuance of Treasury bills. These events, which were widely anticipated, did not initially appear likely to disrupt the functioning of the liquidity market. They occurred in a context where bank reserves, which had been reduced following the contraction of the Fed’s balance sheet, were nevertheless considered sufficient. The tensions observed and the rapid interventions by the Federal Reserve thus called into question the idea that the level of reserves then considered adequate guaranteed the proper functioning of the money market. See Federal Reserve Bank of New York (2021).

[2] Introduced by the Basel Committee as part of the Basel regulations in 2014 and fully implemented from 2018, this prudential ratio requires banks to hold sufficient high-quality liquid assets (i.e., assets that can be quickly sold on the market without risk of loss in value) to meet net cash outflows over a 30-day horizon in a stress situation. It thus aims to strengthen banks’ short-term resilience in the event of tensions in the financing markets.

[3] For the sake of simplicity, we use the terms « bank reserves » and « bank liquidity » interchangeably in this article. Bank reserves are the most liquid financial instrument available to a bank and correspond to the electronic money issued by central banks.

[4] The opportunity cost of holding reserves corresponds to the additional return that a bank forgoes by not investing its funds in a financial instrument with similar characteristics in terms of liquidity and risk, such as a short-term Treasury bill. In a regime of abundant liquidity, rates on short-term Treasury bills are very close to the deposit facility rate, making the opportunity cost of holding reserves low.

[5] See this article by BSi Economics on the concept of reserve requirements.

[6] Interested readers can explore this discussion further in Borio (2023), which argues that the arguments frequently put forward in favor of an abundant reserve regime may be exaggerated. A key point is that the low opportunity cost of reserves is undoubtedly the main factor explaining their high demand in the current regime, and that this opportunity cost varies depending on the regime in place.

[7] The purchase of long-term securities can indeed have a significant impact on the yield curve (this was the aim of the quantitative easing operations carried out by central banks).

[8] A spread is the difference between two interest rates, often expressed in basis points.