Is the union of the Chinese dragon and the African lion nothing but a chimera?

Part 2: WHAT OPPORTUNITIES FOR AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT?

Summary:

– In terms of quality, Chinese investment offers new opportunities in technology transfer and infrastructure development, two areas of crucial interest for Africa’s development.

– Chinese investment seems to contribute positively to technological upgrading of African countries: because the technology used by Chinese firms matches better the existing technologies and the labor skills in Africa than the one used by many Western countries, there is a potential for African countries to acquire them and develop their private sector. However, the “flying geese” model of dynamism observed in Southeast Asia depended on different factors that are unevenly present in Africa.

– Chinese investments and credit lines often provide resources that are often lacking in African states, allowing them to implement much-needed infrastructure projects. But one of the main challenges remains ensuring the maintenance of large-scale infrastructure projects.

– If FDI is expected to play a role in achieving the country’s development objectives, then African governments must implement an active strategy to attract FDI and make it work for the development of their country by using effective incentives.

Chinese investment in Africa generates both unease and fascination. Anxiety about the growing presence of China in the continent is reflected in comments such as those of the U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton « Africa should beware of the ‘new colonialism’ played by China » (The China Times, 2011), or by Wamulume Kalabo, chairperson of the Zambia Chamber of Commerce and Industry: « Their coming to Africa is purely because they want to have some control over raw materials » (2007).On the other hand, Chinese leaders are trying to put these fears to rest, emphasizing the principle of mutual benefit, and many scholars now acknowledge the tremendous opportunities that China brings for Africa’s development. For instance, in the African Economic Outlook 2011, the OECD Development Center argues that Africa benefits not only from direct interactions with China, but that this partnership brings new opportunities for African development (with much-needed infrastructure projects, for example) and increases the political and strategic power of African governments by breaking the monopoly of Western countries.

So what is the real story? Is Chinese investment positive for African development or is the union of the Chinese dragon with the African lion nothing but a chimera?

1. Is more FDI always better?

In theory, FDI is expected to generate growth in the recipient country through direct and indirect links with the local economy. In the neoclassical model, FDI should flow from capital-rich economies to capital-poor economies, thus complementing limited domestic savings and reducing the cost of capital. The indirect benefits of FDI on growth and development are due to the increase in productivity through transfers of technology and skills acquisition, competition (leading to a more efficient use of resources), and exports (Moran et al., 2005). However, these arguments are now considered with more caution. They seem to suggest that the mere presence of FDI is enough to encourage the development of the host country. But is more Foreign Direct Investment always better for economic development?

First, as seen in « Chinese investment in Africa: What Characteristics? », by comparing inward FDI stocks as a percentage of GDP across different regions, it appears that Africa is not left behind but, on the contrary, above average. Once scaled by market size, the ratio is higher for Africa than for the average of developing or developed economies (Te Velde, 2010). This also shows that the private sector in Africa relies heavily on foreign investment and may be a sign that the most urgent matter for policymakers is not so much to attract more investment but rather to stimulate local investment and make the most of existing foreign direct investment.

Furthermore, the key is focusing on the quality of Foreign Direct Investment rather than quantity. The real question should not be « how much FDI can a country attract? » but rather « how can FDI help meet the country’s national development objectives? » Indeed, it seems obvious that a dollar (or yuan) invested in oil will probably be less helpful to Equatorial Guinea’s development in the long term than one dollar in the manufacturing industry, partly because of differences in profit repatriation (ODI 2002). According to UNCTAD (2013), in 2011, 68% of total FDI equity income in Africa was repatriated, compared to 58% for all countries and 44% for all developing economies. However, when excluding the main oil and minerals exporters, the share of repatriated earnings falls to 52% of total FDI equity income in Africa. FDI in natural resource extraction may offer some immediate benefits, but other types of FDI offer more benefits in the long run, especially if they are linked to the local economy and contribute to human capital development and gross capital formation. On the contrary, investments characterized by “extract and export” activities have little national benefits – except some revenue for the government (mainly through export taxes) and relatively high wages for a small group of workers directly linked to the extraction process (Girvan, 1973). Many African countries still rank very high for FDI inflows as a percentage of Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF), which may mean that the investment does not go to the productive sector (see UNCTAD 2013).

In terms of quality, Chinese investment seems to offer new opportunities in technology transfer and infrastructure development, two areas of crucial interest for Africa’s development. The World Bank estimates that the ineffectiveness of investment incentives is partly due to the lack of the requisite infrastructure and labor skills (Broadman 2007). These new opportunities also come with some challenges that African governments will have to face.

2. Flying geese, leading dragon?

Is increased Chinese investment in Africa playing a positive role by providing a model for industrial development and transferring new technologies and ideas? Japanese firms offered a good example of this possibility with their influence on the industrial boom in Southeast Asia, and Japan has been described as the leader of the « Flying Geese » model. According to this model, the international product cycle operates in a manner where countries will switch from the production of low-technology goods to the production of higher-technology goods. For instance, a country will start by producing textiles and simple assembly, and then, as it acquires more knowledge and moves up the learning curve, its products will have more added value. But can China be a leading dragon in Africa?

Chinese investment seems to contribute positively to technological upgrading in African countries. Indeed, because Chinese technologies have been designed to meet local demand, it is much easier for African countries to use and integrate them into their private sector (OECD and AFDB, 2011). In addition, there is a rapidly growing and very large market of poor consumers, and large northern transnational companies (TNCs) are increasingly targeting the « bottom of the pyramid » (BOP) market—as defined by Prahalad (2005): « those 4 billion people who live on less than $2 a day. » Large-scale firms in the south are opening factories in Africa. Because the technologies used by these firms are better suited to existing technologies and labor skills in Africa, there is potential for African countries to acquire them and develop their private sector (OECD and AFDB 2011).

Secondly, although China is present in the extraction of resources, it has also committed itself to the development of new value-adding processing industries, such as refineries or petrochemical complexes, and the exploration of new fields. Chinese investment thus provides African countries with a resource-based economy and an opportunity to export sophistication and self-sufficiency. Deals in the mining and quarrying sector are often combined with either the development of industrial complexes for these sectors or the construction of necessary infrastructure, thus enabling the recipient country to move up the value chain. McKinsey estimates that almost ¼ of the major resource deals included foreign investment in infrastructure or resource processing, compared to just 1% in the 1990s (McKinsey 2010). At the same time, through its investments in the exploration of new fields, China not only satisfies its demand for resources (thereby driving up spot market prices), but also produces a « global public good » by extending fuel and food supplies. For Paul Collier, Africa is one of the largest unexplored resource basins in the world, and future discoveries could be multiples of today’s known reserves (Collier 2010).

Finally, the deployment of a large base of exports and on-site workers executing the projects proved to be an important channel for the transmission of knowledge and expertise. Japan provides an interesting example of this mechanism. Indeed, in the first 20 years of its development cooperation, Japan deployed more than 4,000 Japanese experts in its technical assistance projects (King, 2007), and authors such as Brautigam (2003) stressed the importance of Japanese business networks for the diffusion of manufacturing and industrialization in countries such as Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore. When their own investment networks spread, these so-called « flying geese » became new leaders in the process of industrialization in Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and coastal China (Brautigam, 2003). Thus, the important entrepreneurial diaspora of Chinese migrant workers in Africa represents a similar opportunity for African countries (Mohan and Tan-Mullins, 2009). The number of Chinese migrants in Africa is a source of considerable dispute, because of the difficulty to determine when a migrant is a migrant rather than a resident, as well as because many migrants are unrecorded (see Exhibit 1 for estimation by IRIS). Interestingly enough, there is even a publication of a Mandarin newspaper, “The West Africa United Business Weekly”, printed in Nigeria. Furthermore, to make technology transfer possible, one crucial part is “tacit knowledge” – which can be defined as “knowledge that cannot be codified” (Polanyi, 1967) or “the routines of production that cannot be learnt through manuals but have to be acquired through actual practice” (Khan, 2009) – and the presence of Chinese entrepreneurs and on-site workers in Africa is a good way to encourage the diffusion of new practices and knowledge. Technology transfer is thus as much a social and institutional phenomenon as it is rooted in the acquisition of new technologies.According to China’s Economic and Trade White Paper, Chinese companies actively help improve managerial and technical skills in African countries.By 2010, they had offered training programs for almost 30,000 people working in various fields, including economics, science and technology, agriculture, public administration, medical care, and environmental protection. Moreover, some Chinese enterprises bring their African employees to China in order to train them. In fact, there is also a large and rapidly growing population of African migrants in China, generally underestimated and partly unrecorded. It is important to recognize the two-way dimension of this innovation asset: it is not only Chinese in Africa, but also Africans in China who offer the potential for technology and knowledge transfer.

Finally, research shows that skills are crucial determinants of FDI, together with good infrastructure (Noorbaksch et al., 2001). Surveys conducted amongst TNCs show that the low level of appropriate skills is one of the most important barriers to investment in Africa. So the positive effect of Chinese investment in technology and skills upgrading can be the beginning of a virtuous circle, as a more skilled workforce attracts more investment and helps local firms better capture knowledge spillovers (Te Velde 2002).

However, the technology transfer of Chinese industrial investment may be limited to a few African countries. Brautigam (2008) emphasizes that the « flying geese » model of dynamism that was observed in Southeast Asia depended on different factors that are unevenly present in Africa. First of all, there must be local investment, with joint ventures that spread skills to local entrepreneurs. In many African countries, the partner is the government. Secondly, it required a « push » from the partner’s country. But Chinese labor costs are more or less similar to those of many African countries, and the productivity of Chinese workers is often better (Brautigam 2008).

In many countries, Chinese investment is quite isolated geographically, thus lowering the possibilities of technology transfer. In addition, the Special Economic Zones (SEZs), in which the Chinese are investing heavily, still have to prove their potential for value addition and skills transfer. In 2010, six Chinese SEZs were active or under construction in Africa, but it is important to remember that not all of them can be expected to have positive impacts—in the same way that Export Processing Zones have not always helped meet the development objectives of the recipient country. First, because the number of SEZs in Africa is still very small, so it is unlikely that they will spark a significant industrial push for the whole continent. Secondly, Chinese firms are very secretive and protect their knowledge (just like most firms), and technology spillovers will not happen unless there is a clear contract to share knowledge (OECD and AFDB 2011). The fact that Special Economic Zones will bring skills and technology transfers to the recipient country depends heavily on the policy framework and implementation (Brautigam and Tang, 2011). Thus, it is crucial for African governments to plan the transfer of shareholder relations in the long-run, just like China did with its own SEZs. In the case of Special Economic Zones and of Chinese investment in general, it is crucial that African governments negotiate better conditions in their deals with Chinese firms, emphasizing the importance of technology transfer.

3. Infrastructure: Demand meets Supply

The large gap in infrastructure in Africa is perceived as one of the most serious constraints to the continent’s economic and social development. Africa faces unmet needs in the provision of water, power, and transportation. The Centre for Chinese Studies estimates that African countries are producing only 7% of their technical hydropower potential, which is extremely low compared to other regions of the world (33% in South America, 75% in Europe, and 69% in North America). Almost 20% of African households still have no electricity, and most countries suffer from frequent power cuts (Centre for Chinese Studies 2011). Unreliable power supply leads to losses in industrial production valued at 6% of turnover. According to World Bank enterprise surveys, 50% of firms in sub-Saharan Africa identify electricity as a major constraint. In addition, transport costs in Africa are among the highest in the world. Africa’s infrastructure services—even though limited—cost more than those available in other regions of the world. For instance, according to the World Bank, road freight costs per kilometer are two to four times higher in Africa than in the United States, and travel times along key export corridors are almost three times longer than in Asia. Globally, Africa’s weak infrastructure is estimated to be costing one percentage point per year of per capita GDP growth (World Bank 2008). The continent’s significant needs are obvious when compared to the BRICs (Exhibit 2).

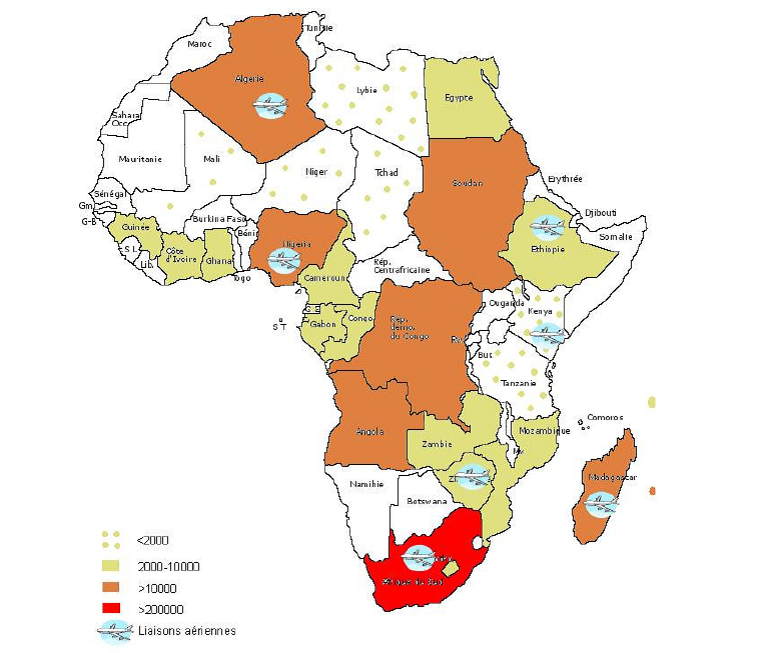

China has been partly filling this gap through its infrastructure investment and financing. Indeed, since 2005, China’s total infrastructure commitments in Sub-Saharan Africa are even superior to those of the World Bank (see Exhibit 3). According to the China Economic and Trade Cooperation White Paper (2013), in 2012, construction contracts completed by Chinese enterprises are estimated at $40.8 billion in Africa, which represents an increase of 45% since 2009. It represents more than 1/3 of China’s total overseas contract work completed. Chinese investments and credit lines often provide lacking resources to African states allowing them to implement much needed infrastructure projects. Between 2010 and May 2012, China approved $11.3 billion in concessional loans directed to 92 African projects. The Addis Ababa-Adama Expressway in Ethiopia and the Kribi Deep-water Port in Cameroon were both financed through concessional loans. (People’s Republic of China, 2013) The fields where China is most present are the power and transport sectors.

China is very active in the power sector, with the construction of large hydropower schemes. According to the World Bank, in 2007, China provided $3.3 billion aimed at the construction of 10 big hydropower projects. They are supposed to increase by almost 30% the total hydropower generation capacity of Sub-Saharan Africa (World Bank 2008). In 2010, the Malabo Gas Plant project was launched in Equatorial Guinea by Chinese firms. Once completed, the project should provide Equatorial Guinea with a complete power supply system, from power generation to power transmission and power transformation (People’s Republic of China, 2013).

One of the major Chinese investment areas in Africa is the rail sector. China’s financing commitments approach $4 billion and include the rehabilitation of 1,350 km of railway lines and the construction of around 1,600 km. This is all the more impressive when considering that the railroad network of the entire continent is only 50,000 km (World Bank 2008). China is now the largest construction market, and its construction sector has experienced an annual growth rate of nearly 20% since the beginning of the decade. Chinese contractors are especially known in the road and water sectors and are present in Ethiopia, Tanzania, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. However, the World Bank estimates that no more than $700 million has been assigned to the two sectors together, which is less than in the other two sectors (World Bank 2008). Moreover, the substantive impetus given by some EP to the financing and building of transport infrastructure, including cross-border corridors, is a concrete contribution to regional integration (OECD and AFDB 2011).

SEZs also have a catalytic effect on investment in Africa, in particular they have a positive effect in the region because they generally involve massive infrastructure investment. According to China’s Economic and Trade White Paper, China is currently creating six economic and trade cooperation zones in Egypt, Ethiopia, Mauritius, Nigeria, and Zambia, and has invested $250 million in infrastructure construction.

Understandably, there may be some concern regarding these large-scale infrastructure projects. The failure of many huge projects during the economic boom in the 1970s became an infamous symbol of inappropriate development strategies. Stories of useless highways, hospitals built with no doctors to work there, and empty schools are very common. According to the African Economic Outlook, it is obvious that investment decisions should be properly budgeted for and linked directly with the country’s development strategy. This is all the more important with deals involving « resources for infrastructure » because it is very difficult to evaluate their entire cost. The complexity of the financial packages used by the Chinese, combined with the opacity that often characterizes these deals, makes it hard to assess the real cost that African countries will have to bear. Projects must be sustainable not only in the current economic conditions but also if there is economic trouble (OECD and AFDB 2011).

History makes it clear that one of the main challenges is also to ensure the maintenance of large-scale infrastructure projects. This is a question of finance and capacity building in African administrations (how is infrastructure maintained, at what cost, what planning effort is required). First, it involves covering the maintenance costs of large infrastructure projects recently financed or constructed by emerging donors. But the responsibility does not lie solely on the shoulders of African governments. A long-term commitment on the part of the partners is equally important.

Creating links between different infrastructure projects appears to be the best way to make full use of their potential network effects. The successful example of Southeast Asia shows that countries that have managed to create infrastructure networks experience positive socio-economic impacts. However, in Africa there seems to be no evolution from single projects to infrastructure networks, and the macro-impact remains limited (Shimomura, 2011).

4. The way ahead: Including these investments in a national strategy

Economists and journalists often raise the question: « China has a strategy for Africa, but does Africa have a strategy for China? » Of course, the need for a strategy did not arise with the increase in investment from China and is no less important for Africa’s partnership with Western countries. However, with Africa attracting more FDI inflows and Chinese investment offering new opportunities and challenges, this need has become more pressing. If FDI is expected to play a role in achieving the country’s development objectives, then African governments have to implement an active strategy to attract FDI and to make FDI work for the development of their country by using effective incentives.

The first step would be to identify the countries’ needs and objectives. Africa is not a homogenous continent, and needs and risks vary greatly between the different countries. In their report « Lions on the Move: The progress and potential of African countries, » McKinsey identifies four groups of countries according to their growth perspectives (McKinsey Global Institute, 2010).

Oil exporters: Oil and gas exporters have the highest GDP growth and have the capacity to finance and attract investment. However, their manufacturing and service sectors are weak. The challenge for them is to allocate resources to effective investment projects (and not overinvest) and to encourage technology transfer and investment in infrastructure.

Diversified economies: These countries have a developed service sector that accounts for a significant part of their growth and attracts a large share of foreign direct investment. However, their labor costs are higher than those of China or India, and they need to move up the value chain to compete in higher value-added industries. They still face some infrastructure challenges and must improve their education sector.

Transition: These countries have lower GDP growth but are growing rapidly. The most pressing challenge for them is to improve both their infrastructure and regulatory system. The penetration rate of key services is extremely low and represents an opportunity for investment.

Pre-transition: Africa’s pre-transition economies have very low growth and many are facing political instability. They lack basic infrastructure and need to create a more reliable business environment.

Of course, the categories described above are general and needs may vary among countries in the same group. African governments have to clearly define the most pressing challenges that need to be addressed and prioritize investment in projects that deliver more benefits. Investors also carry different skills and risks, and for instance China’s comparative advantage in infrastructure construction can be useful. Furthermore, as seen before, the fact that China invests in many countries that usually attract fewer investment, like Ethiopia, represents a tremendous opportunity for countries in the pre-transition and transition group to overcome their lack of infrastructure and move up the value chain.

Another important point is to include FDI in a well-defined and accepted national strategy. There is no « magic potion, » and FDI cannot be the solution to all development problems, nor can domestic investment, aid, or trade. They all carry different opportunities and challenges, and African governments should examine how FDI fits their development objectives.

Once the priority investment field is identified, African governments should approach and attract investors. The African Economic Outlook stakeholder survey [1] provides an interesting insight. It shows that in most cases it is the emerging partner that initiates the partnership. Local experts estimate that only 4% of African countries initiate partnerships with emerging countries with a clear strategy (Exhibit 4). It is obvious that African governments must adopt a more active strategy to attract FDI from China and other emerging countries.

Another important aspect for designing an appropriate and efficient strategy is involving local stakeholders. This is the best way to achieve transparency and also helps identify all the needs and challenges facing the country. The African Economic Outlook survey shows that in most cases, the management of partnerships with emerging countries lies in the hands of the head of state or a few ministers. This is a risk for the country because the partnership depends heavily on a few key individuals and can be broken more easily. Moreover, the fact that in many African countries joint ventures with Chinese partners are formed with the African government rather than local entrepreneurs is a constraint to knowledge transfer. It also makes the investment strategy adopted by the country less legitimate for the population. This is a risk for the African government as well as for Chinese investors. An « anti-China » sentiment is growing in many parts of Africa, and this is partly due to the fact that there is a dichotomy between the people and the government. There is a lack of communication, and Chinese enterprises are not in direct contact with local stakeholders.

The figure plots answers to the following question: « To what extent is each local stakeholder below involved in the partnership with emerging partners? » (with 0=not at all, 1=somewhat, 2=important, 3=very important)

Finally, regional coordination is also crucial to attract FDI and foster economic development. China’s increased interest in Africa has opened up new possibilities for African countries. However, Africa will not be able to make the most of the competition among its partners if African countries remain divided. Regional coordination should help African countries make the most of FDI by increasing their political and economic power. The OECD states that “as long as Africa remains divided, it will not be able to make the most of the competition amongst partners. To acquire a critical mass for negotiations, African governments must coordinate policies more effectively” (OECD and AFDB 2011). Moreover, according to Brautigam (2008), creating an investor-friendly environment is a crucial requirement for a “flying geese” model to work. In order to create an investor-friendly environment, it seems important to encourage regional coordination and a more homogeneous regulatory policy. The regulatory framework varies greatly between countries. Obtaining permits appears to be quite difficult and time-consuming in many countries, and there are many unnecessary regulations that could be removed. Investment promotion agencies often lack resources and are unable to implement consistent FDI policy and do not have enough power to decide on relevant issues.African governments should implement policies related to education, technology, competition, or privatization without engaging in policy reversals, which create uncertainty. According to World Bank enterprise surveys, 22% of firms in Sub-Saharan Africa identify customs and trade regulations as a major constraint, compared to 7% in OECD countries and 12% in South Asia. The cost structures of African countries still constrain mutual trade and are a significant barrier to investment.

On the other hand, tax exemption should be done carefully. It is important that African countries avoid a race to the bottom in order to attract more FDI. To win the competition to attract Foreign Direct Investment, African countries often offer generous – and unnecessary – fiscal incentives to foreign firms. One of the consequences is that they have less revenue in taxes and thus governments are less able to implement policy to foster domestic investment, growth and poverty reduction. The only sustainable solution to attract market-seeking and not only resource-seeking FDI is to create a good investment environment and an efficient domestic market (UNCTAD 2010). In addition, the fiscal costs of Special Economic Zones need to be carefully estimated. The African Economic Outlook 2010 underlined the risks of treating local and foreign owners of capital differently for public resource mobilization in the short and long term. Indeed, the government will certainly lose from SEZs tax exemptions the revenue it needed to finance infrastructure and services. Further, these tax exemptions provide a negative demonstration effect for local residents already investing in the country and give incentives to entrepreneurs declaring their activities as part of the SEZ (OECD and AFDB 2011).

UNCTAD’s new FDI Contribution Index shows relatively higher contributions by foreign affiliates to host economies in Africa, in terms of value added, employment and wage generation, tax revenues, export generation, and capital formation. Comparing the FDI Contribution Index with the weight of FDI stock in a country’s GDP shows that a number of countries (South Africa, Morocco, Egypt, for instance) get a higher economic development impact “per unit of FDI” than others, confirming that policy is crucial in order to maximize the positive and minimize the negative effects of FDI. Comparing the FDI Contribution Index with the weight of FDI stock in a country’s GDP, it appears that countries which attract FDI largely thanks to their fiscal regime receive FDI with little impact in terms of local value added or employment. (UNCTAD 2012)

Conclusion

Contrary to fears reflected in many press articles, evidence suggests that Chinese investment is not only resource seeking but also carries a lot of opportunities for Africa’s development, especially for knowledge transfer and infrastructure development. Indeed, Chinese investment seems to contribute positively to technological upgrading of African countries, both with direct investment and with the presence of Chinese entrepreneurs and on-site workers that will spread the tacit knowledge and skills. In addition, Chinese investment in infrastructure is filling the large gap and answers the unmet needs of African countries in the provision of energy and transportation. However, these opportunities still need to be seized, and the most pressing challenge for African governments is to define a strategy for how investment projects are to be used in the context of broader national development. A road alone—even a long one—will not miraculously translate into huge growth rates if it is not part of a broader strategy to foster certain industries (coherent industrial policy) or create Lewis-model-like rural-urban linkages (coherent agricultural policy). Vision, ownership, and regional coordination are the best ways to turn the opportunities offered by economic partnerships—China and others—into shared and sustainable growth in Africa. While China often presents its investments in Africa as a « win-win strategy, » which in many respects seems to be true, the question should also be « who wins how much? »

Notes:

[1]Stakeholder survey methodology: The African Economic Outlook country note authors on fact-finding missions for the economic assessment and macroeconomic forecast gather data from the National Statistical Office and conduct interviews with a range of government officials and representatives of the private sector, civil society, and international organizations. In 2011, a special survey was designed to capture and compare the results of interviews with African stakeholders on emerging partners’ activities. Responses were collected for 40 countries, representing 83% of the African population and 92% of the continent’s GDP. The survey uses qualitative measures on a 4-point scale aimed at providing subjective indicators. Where applicable, answers were weighted according to GDP or FDI.

References

– BRAUTIGAM D. (2003) Close Encounters: Chinese Business Networks as Industrial Catalysts in Sub-Saharan Africa, African Affairs.

– BRAUTIGAM D. (2008)‘Flying geese’ or ‘hidden dragon’? Chinese business and African industrial development. In: D. Large, J.C. Alden and R.M.S. Soares de Oliveira (eds.) China Returns to Africa: A Rising Power and a Continent Embrace. London: Christopher.

– BRAUTIGAM, D. and X. TANG, (2011). African Shenzhen: China’s special economic zones in Africa. Journal of Modern African Studies, 49 (1).

– BROADMAN, H (2007). Africa’s Silk Road: China and India’s New Economic Frontier. Washington DC, World Bank.

– CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES, (2011). Bridges over Troubled Water: Chinese Infrastructure Projects and African Standards. The China Monitor, 62.

– COLLIER, P. (2010), The Plundered Planet: Why We Must –and How We Can – Manage Nature for Global Prosperity. New York: Oxford University Press, April 2010

– DAHMAN-SAÏDI, M & WOLF,C (2011), RECALIBRATING DEVELOPMENT CO-OPERATION: HOW CAN AFRICAN COUNTRIES BENEFIT FROM EMERGING PARTNERS?,OECD Develoment Centre, Working Paper, No. 302.

– GIRVAN, N. (1973), The Development of Dependency Economics in the Caribbean and Latin America: Review and Comparison, Social and Economic Studies, 22 (1)

– KING, K (2007), China’s Aid to Africa: A View from China and Japan. University of Hong Kong.

– KHAN, M. H., (2009). Learning, Technology Acquisition and Governance Challenges in Developing Countries. Project Report. London: Department for International Development.

– MCKINSEY GLOBAL INSTITUTE, (2010). Lions on the Move: The progress and potential of African countries. McKinsey publication

– MOHAN, G. and M. TAN-MULLINS, (2009). Chinese migrants in Africa as new agents of development? An analytical framework. European Journal of Development Research, 21(4).

– MORAN, T. H., E. M. GRAHAM and M. BLOMSTROM (2005). Does Foreign Direct Investment Promote Development? May 2005, 440 pp. ISBN paper 0-88132-381-0

– NOORBAKHSH, F., A. PALONI and A. YOUSSEF (2001), Human Capital and FDI inflows to Developing Countries: New Empirical Evidence, World Development, 29.

– OECD and AFDB, (2011). African Economic Outlook – Africa and its Emerging Partnerships. Paris : Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development – Development Center and African Development Bank.

– PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA (2013). China-Africa Economic and Trade Cooperation, Information Office of the State Council, August 2013 Beijing.

– POLANYI, M., (1967). The Tacit Dimension. Garden City NY: Doubleday Anchor.

– PRAHALAD, C.K., (2005). The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty through Profits. New Jersey: Pearson Education/ Wharton School Publishing.

– SHIMOMURA, Y., (2011). Infrastructure Construction Experiences in East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa: A Comparative Study for Mutual Learning. SOAS International Workshop on Aid Effectiveness The Role of Infrastructure and Capacity Development in East Asian Growth and Its Implication for African Development. Tokyo: Japanese International Cooperation Agency.

– TE VELDE D.W. (2002),Foreign direct investment for development: Policy challenges for Sub-Saharan African countries. Overseas Development Institute (ODI), London

– TE VELDE D.W. (2006),Foreign Direct Investment and Development: An historical perspective. Overseas Development Institute (ODI), London,

– THE CHINA TIMES, Clinton Warns Africa Against “China’s Neocolonialism” http://www.thechinatimes.com/online/2011/06/154.html

– UNCTAD, (2001). World Investment Report 2001. Promoting Linkages. Geneva : United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

– UNCTAD, (2010a). South South Cooperation – Africa and the New Forms of Development Partnership. Economic Development in Africa Report 2010. Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

– UNCTAD, (2010b). World Investment Report 2010. Investing in a Low-carbon Economy. Geneva : United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

– UNCTAD, (2012). World Investment Report 2012. Towards a New Generation of Investment Policies. Geneva : United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

– UNCTAD, (2013). World Investment Report 2013. Global value chains: Investment and trade for development. Geneva : United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

– WORLD BANK, (2008). Building Bridges: China’s Growing Role as Infrastructure Financier for Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington , D.C.: World Bank.