Abstract:

· The emergence of the renminbi and the appreciation of the dollar are likely to lead to a measured rebalancing of the region’s exchange rate policies in favor of the Chinese currency

· This rebalancing is not as revolutionary as it may seem and remains limited by the mistrust of countries in the region towards their large neighbor China, with the US dollar ultimately retaining its status as the leading currency in international economic and financial exchanges

· The most profound change in monetary policy will probably be based on an increasingly domestic price-focused approach

· This phenomenon, made possible by the economic and financial development of these countries, will be accompanied by a strengthening of macroprudential policies.

In a previous article, we saw how the historical construction of a monetary policy community in ASEAN 6[1]was linked to outward-looking development strategies (commercially and financially) and a regional monetary history, with the aim of achieving exchange rate stability.

Changes in the internal and external environment make historical analysis a necessary but insufficient framework for understanding the situation. The international monetary tectonics currently at work have the potential to cause significant disruption to countries that rely on external financing and are concerned about the stability of their exchange rates. After analyzing the effects of external changes, we will see that these changes are part of fundamental internal dynamics in the evolution of monetary policy conduct.

- Desynchronization and the emergence of the yuan

The events of summer 2013[2] highlighted the sensitivity of countries in the region to the international environment. At a time when the monetary policies of the major central banks (Japan, Eurozone, United States, and United Kingdom) are diverging and China is displaying its external monetary ambitions (internationalization of the Renminbi, proliferation of SWAP agreements, entry into the IMF’s SDR basket), this environment is changing.

a. Stability still centered on the US dollar (USD)

Since the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1976, the role of the USD as the central currency in the international system (reserve and exchange) has been almost constantly called into question. After the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights, the emergence of the yen and the mark, and then the euro, it is now the internationalization of the Chinese currency (RMB) that could challenge the USD in the long term. Due to its position on the map of trade and financial flows, ASEAN is at the forefront of this new monetary competition. While a hypothetical hegemony seems to be under threat in the region, the central role of the USD has not been challenged over the last decade.

The emergence of the RMB as a means of payment has been undeniable since the Chinese authorities began pursuing internationalization in 2010. While this has led some to talk about the existence of a Renminbi bloc[3], subsequent studies have highlighted the preeminence of the USD in exchange rate fluctuations[4]. The opening of numerous SWAP lineslinesbetween the region and the Fed during the 2008 crisis, followed by the establishment of lasting intra-regional agreements in USD, confirmed its status as a reserve currency. A new international monetary dynamic has brought this leadership into a phase of unprecedented turbulence.

b. The effects of a sustained appreciation of the USD

Indeed, the significant economic and financial turmoil of recent years has taken place against a backdrop of depreciation of the US currency, fueled by the Fed’s ultra-accommodative policy. However, at a time when the Fed appears to be gradually moving towards normalizing its monetary policy, bucking the trend of other major monetary centers (China, Japan, the eurozone), the appreciation of the USD, which has already begun, appears to be sustainable. As we explained in the previous article, such a move runs counter to the preferences of countries in the region, which are reluctant to see their currencies appreciate (« appreciation aversion »). This aversion is reinforced by: a widespread regional slowdown in growth and trade; a reversal of the RMB’s appreciation trend against the backdrop of the Chinese economy’s soft landing; and sustained downward pressure on the yen.

Leaving aside specific, cyclical factors (falling commodity prices, political crises), there is a fundamental trend towards an adjustment of exchange rates against the USD in line with other major regional currencies. Once again, the serious, interventionist policy of the Singaporean authorities, who have announced a temporary devaluation of their currency against the USD, illustrates the regional dynamic. However, this correction in exchange rates, limited in scope by each country’s USD debt, does not call into question the fundamental structure of the ASEAN currencies’ place in the international monetary system.

c. Towards an amended pegging system in favor of greater multipolarity

The emergence of China and its currency as a major player in the regional economic environment appears, in the long term, to be something that only a major internal political crisis could hinder. Consequently, a strengthening of its influence in the conduct of the region’s exchange rate policies seems inevitable. The appreciation of the USD, which is likely to weaken its link with the ASEAN 6 currencies for a few years, will facilitate this rise in power. However, recent regional history shows that this is not so revolutionary. Successively, the Japanese and Chinese currencies have seen their roles hampered by their appreciation. A quick glance at exchange rate movements against the USD illustrates the different phases of regional monetary tectonics.

Ultimately, two constants remain: the fear of appreciation and the central (but not hegemonic) role of the USD. Current external events, while they may lead to significant periods of adjustment, are not likely to challenge these characteristics, especially since the rise of the Chinese currency remains capped by its neighbors’ significant lack of confidence in it.

The history of international monetary tectonics teaches us that, despite the often sudden nature of monetary crises, changes in the (formal or informal) anchors of these policies are gradual, long-term processes. For the region, beyond temporary adjustments, the impact of international monetary events, although widely documented, seems limited. However, the pitfall of monetary policy analyses is often to omit the fundamental factor behind changes in monetary policy: the internal dynamics of countries, which are undergoing profound change.

-

Economic development, the driving force behind an increasingly introspective approach to monetary policy

The existence of large countries that have industrialized with heterodox monetary policies (South Korea) and the absence of industrialized countries pursuing such policies leads to a reversal of the accepted causality between « modern » monetary policies and development. The conduct of monetary policy would therefore be more determined by a stage of development than it would determine it.

a. Development and monetary policy channels

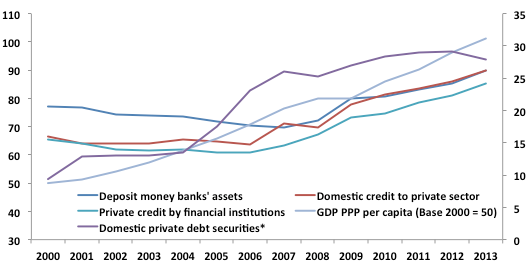

Despite the setback in 1997, the ASEAN 6 countries have experienced thirty years of intense economic and financial development. On average, real income per capita has tripled in twenty-five years. A banking system has developed. Financial markets have deepened and diversified. These exceptional phenomena are profoundly changing the interactions between the real economy and monetary policy.

Development of financial systems in ASEAN 5

Note: *Vietnam is not included; data are simple averages of % of GDP

Sources: World Bank, BSI Economics

The development of the financial system relies more on private debt (bank debt, bonds). In a financialized environment, monetary policy not only affects the cost of credit via interest rates, but also indirectly affects the economy through market participants’ expectations and wealth effects linked to asset prices (Tobin’s q, balance sheet channel, household wealth).

At the same time, economic development is accompanied by the formation of a more diversified consumption basket in which agricultural products and raw materials play a less important role. However, the prices of these products are highly dependent on world markets. The reduction in their weight in the average consumption basket and therefore in the consumer price index makes internal monetary stability[6] more directly linked to the country’s economic cycle and monetary policy.

Changes in transmission channels and greater endogeneity of inflation require an adjustment of monetary policy objectives, tools, and modalities.

b. « Modernization » of monetary policies

Often guided by the discreet advice of the IMF, the ASEAN 6 countries have been able to accompany their economic development with a modernization of their monetary policy management. Over the last twenty years, almost all countries have adopted explicit inflation targets based on consumer prices, at the expense of money supply targets. These targets are increasingly central to communications, which are also undergoing rapid development. The 1997 crisis led to the addition of an explicit financial stability target and the gradual adoption of macroprudential policies (a point we will return to below), often ahead of industrialized countries.

Monetary authorities, which are rarely independent in practice, have improved their transparency, communication, and data quality by using modern central bank tools. The policies pursued, the results achieved, and the foreign exchange reserves accumulated make monetary authorities the benchmark entities in uncertain environments where corruption persists. This ongoing modernization effort is based on a theoretical framework that has undergone significant changes recently.

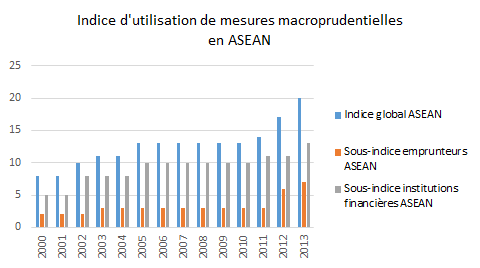

c. Macroprudential tools in developing countries: the solution for combining independence, openness, and stability

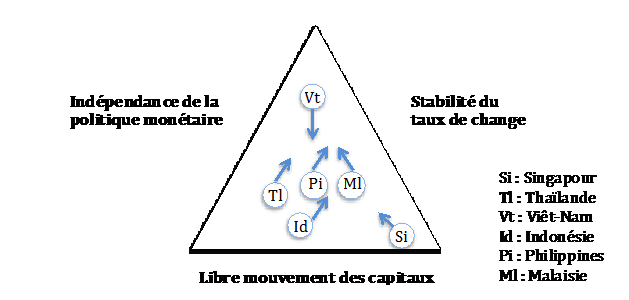

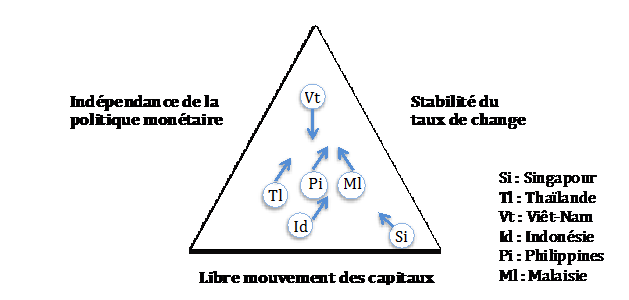

For nearly half a century, the incompatibility triangle, known as Mundell’s triangle, served as a reference for analyzing the strategic choices available to monetary policy. Free movement of capital, monetary policy independence, and external currency stability could not coexist. One had to be sacrificed in order to fully enjoy the other two. The choice of the ASEAN 6 countries, with the exception of Singapore, was therefore to combine a little of all three (see chart).

Monetary policies in ASEAN 6 and Mundell’s triangle

Note: the positioning of countries represents, at the author’s discretion, their monetary policy choices from 2005 to 2015; the arrow indicates their evolution over this period

Sources: BSI Economics, The Chin-Ito Index

In a 2013 article, Rey questions this triangle due to the concurrence between national and international monetary cycles as dictated by the Fed. The « trilemma » would be nothing more than a dilemma between the Fed’s independence and the free movement of capital. In line with this article, studies assert that in open developing countries, a policy of raising interest rates could be expansionary due to capital inflows[7]. Push factors (factors related to capital supply) take precedence over pull factors (factors related to capital demand), and international conditions prevail over national ones. However, there is a solution that can restore flexibility to monetary policy while contributing to the achievement of its ultimate objectives: an active macroprudential policy.

Source: The Use and Effectiveness of Macroprudential Policies: New Evidence, IMF 2015

A recent tool that has become popular among researchers and central bankers in developed countries, macroprudential policy covers active prudential policies that address the financial system as a whole, with the aim of limiting the risks of global collapse (reducing systemic risk). This tool could prove decisive for developing countries that are open to international capital. In addition to preventing sectoral bubbles and systemic risks and directing capital, a well-used macroprudential policy could insulate the country from international cycles and thus restore monetary policy’s role as an internal stabilizer.

Conclusion

Thepromise of macroprudential policy remains largely unexplored (both theoretically and empirically), yet the monetary policies of the ASEAN 6 in the coming years are likely to be highly innovative in this area.

Let us not forget that monetary policy is a support function for the real economy. It therefore remains dependent on the country’s development path and its success in implementing it, and that the changes it seeks cannot materialize unless the health of the real economy (to which it obviously contributes) allows it.

Bibliography:

Monetary policies: what changes with the crisis? C. Bordes, Problèmes économiques (2013)

Does the new dynamic of international capital flows that emerged after the 2008 crisis strengthen the stability of the international monetary system? F. Berthaud; French Treasury (2015)

Dilemma not Trilemma: The global financial cycle and monetary policy independence, H. Rey; Jackson Hole Symposium (2013)

Two Targets, Two Instruments: Monetary and Exchange Rate Policies inEmerging Market Economies; Ostry, Ghosh & Chamon (2012)

Approximating Monetary Policy: Case Study for the ASEAN-5; A. Ramayandi, Department of Economics, Padjadjaran University (2007)

The Use and Effectiveness ofMacroprudential Policies: New Evidence, IMF (2015)

Notes:

[1]For the sake of brevity and consistency, only the most economically significant countries will be discussed: Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Singapore, and Vietnam.

[2]The « taper tantrum, » when the first signs of the end of QE3 in the United States and thus of the cheap dollar had a strong impact on regional currency exchange rates by generating significant capital outflows (see this article on BSI Economics)

[3]The Renminbi block is here: rest of the world to go?, A. Subramanian, M. Kessler, Peterson Institute, 2013

[4]Is there really a Renminbi bloc in Asia, M. Kawai, V. Pontines, ADB Institute, 2014.

[5]Agreement between two contracting parties on a right that can be exercised during a specified period of time to exchange currencies for a capped amount.

[6]Determined on the basis of changes in the consumer price index calculated from the average consumer basket.

[7]Tools for managing financial-stability risks from capital inflows; Ostry, Ghosh, Chamon, Qureshi (2012)