Summary:

– A development trap is often defined as a phase of slowdown or stagnation in growth following the rapid catch-up of an economy that has managed to enter the group of « middle-income » countries.

– Some developing countries are at risk of falling into this trap because the convergence process is highly unstable due to double-edged dynamics.

– The mobilization of rural workers, investment, and foreign technologies enable development. At a certain point, this can turn into a dead end.

– Demographics play a key role because they enable the working population to grow and then decline: some countries could become old before they become rich.

– Institutional dynamics will either ensure or prevent a country’s sustainable development: in particular, the ability to adapt and make long-term forecasts will play a key role.

Although there is no formal definition of the phenomenon, a development trap is often defined as a phase of slowdown or stagnation in growth following the rapid catch-up of an economy that has managed to enter the group of « middle-income » countries [1].

Indeed, some emerging countries experience a relatively sharp economic slowdown once they reach middle-income status and convergence stops. The economy in question finds itself caught between two stools: it is neither a low-wage economy nor an innovative economy.

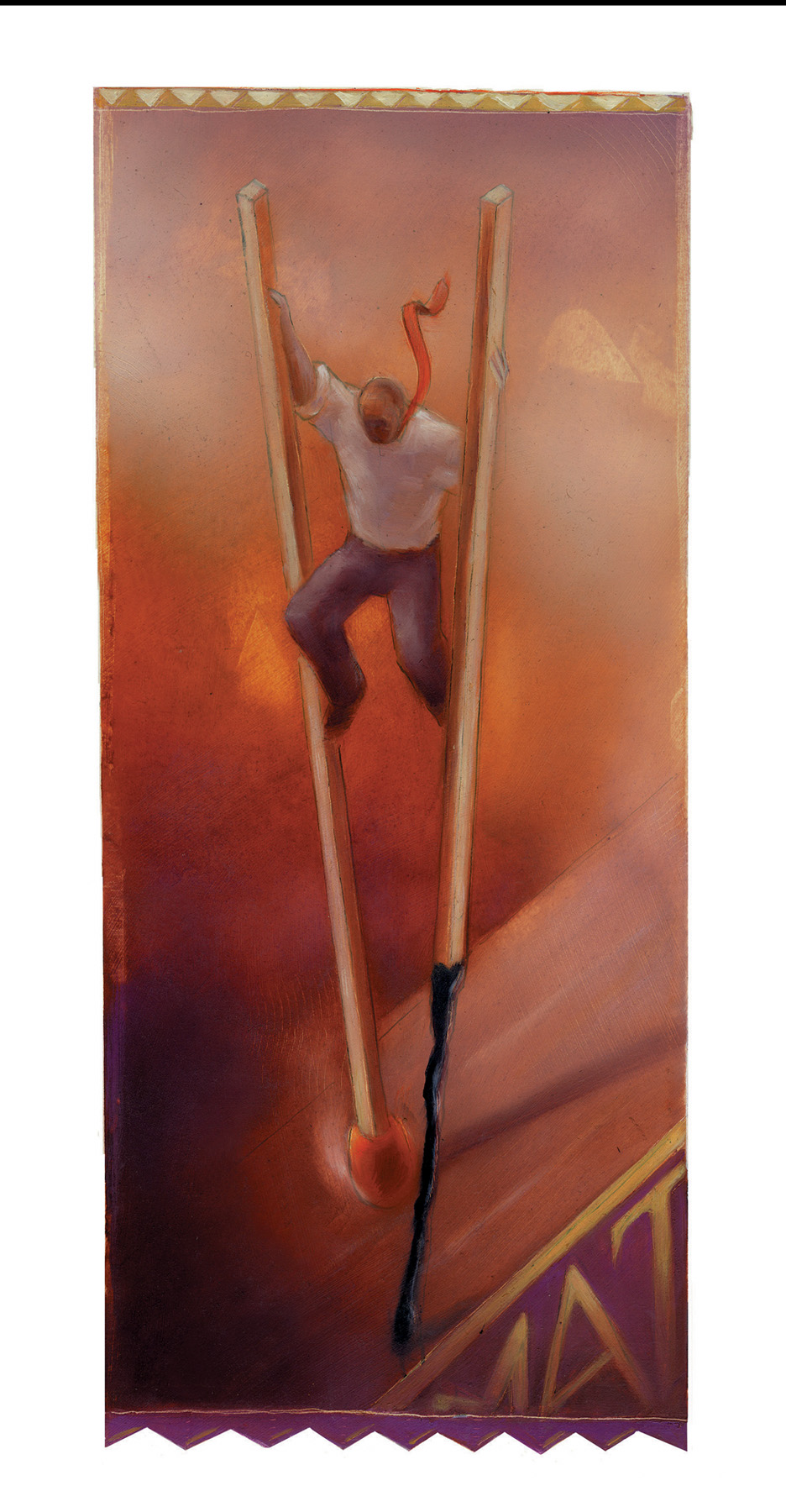

More qualitatively, countries that fall into the development trap face governance problems and suffer from an overly short-term view of development. There is a path to growth for all countries, but it is extremely long and fraught with pitfalls: it is very easy to stray from it and quickly find oneself lost if stakeholders become complacent and overconfident. Countries must be the drivers of their own growth with a well-defined strategy rather than mere observers undergoing a random process. We can cite Rodrik’s work on Growth Diagnostics or Growth Strategies: development is seen as a quest in which certain stages must be unlocked one after the other in a specific order.

Emerging countries on a knife edge

Although development is sometimes seen as a fairly linear and almost automatic phenomenon (see Solow’s model [2], which remains the benchmark for analyzing economic growth), in reality, convergence is punctuated by « hills, plateaus, mountains, and plains, » according to L. Pritchett, a development economist at Harvard. A country’s development is far from systematic and instead corresponds to an extremely fragile balance of several interrelated factors that enable growth to take off but do not necessarily ensure its sustainability.

Significant efforts are required to join the club of rich countries. Between 1960 and 2012, out of 101 developing countries at the time, only 13 became developed economies [3]. East Asian countries performed relatively best, while South American countries struggled the most.

Development is above all a successive series of dynamics which, when combined, determine the scale and sustainability of convergence. In this paper, we will focus on the economic, demographic, and institutional dynamics of development, leaving aside other equally important dynamics such as educational and financial dynamics, for example.

Economic dynamics

At the beginning of their economic catch-up, developing countries grow faster than developed countries thanks, among other things, to the use of foreign technologies: this is known as the advantage of being late (Gershenkron, 1962). It should be borne in mind that growth can be broken down into three parts: capital accumulation, labor force participation, and total factor productivity (TFP or Solow residual).

In general, a poor country can accelerate its growth by reallocating low-productivity rural workers to industry, where productivity is higher. At an early stage of development, an economy will benefit all the more from importing existing technologies to increase productivity and begin its convergence process. Low-income countries can thus compete in international markets by producing low-cost labor-intensive goods and imitating technologies that are easily accessible to workers who are still relatively unskilled. By heavily subsidizing industrial investment and infrastructure, governments will encourage the emergence of overcapacity in certain key sectors in order to create export surpluses and kick-start the catch-up process.

However, the reproduction of technologies is not a panacea; the industries that use them must appropriate them and adapt them to the national context. This is what Japan did during the Meiji era (1868-1912), for example, adapting European technologies to its own characteristics (high capital costs and low wages), which were different from those of Western Europe (low capital costs and high wages). In contrast, India, which was an industrial leader in the early19th century with characteristics similar to those of Japan in terms of relative prices, failed to do this work to maintain its dominant position.

The greater participation of agricultural workers reduces the available pool of new workers involved in the industrialization process. This creates a vicious circle at a certain level of development, as wages are then pushed up. The country’s competitiveness deteriorates in terms of both prices and exchange rates. The country becomes less and less competitive, and competition on international markets increases as new countries also begin the development process. In fact, if the country has not been able to move upmarket (due to insufficient innovation efforts and an education policy that is still in its infancy), it is now becoming uncompetitive in the low-end products that enabled it to begin its economic catch-up.

If the imitation of foreign technologies, which enabled initial convergence, does not translate into « local » innovation, or at least if the population’s level of education is not high enough to be able to use more sophisticated innovations, then the country risks falling into an imitation trap. The innovative sector is not effective due to (i) a shortage of skilled labor or an inability to mobilize it, (ii) inadequate infrastructure, and (iii) a dysfunctional institutional system. This discourages both the population from pursuing education and businesses from innovating, thereby perpetuating the economic slowdown. Education and employment opportunities for educated workers are often one of the main challenges of development: We do need education! Moreover, economic slowdown is often due to a decline in TFP following a convergence of the technological frontier.[4], which acts as a barrier if the country has not accumulated enough human capital and is not ready to take over. The country then enters a vicious circle: structural change towards an economy of innovation and high value-added services is hampered, and growth slows down.

Finally, capital accumulation that becomes too large and somewhat superficial can quickly become dangerous because it reduces capital productivity, increases debt, and encourages ever more investment. This is roughly the direction China has taken in recent years, leaving it vulnerable to a backlash in the years to come.

Demographic dynamics

In general, apart from emerging Europe, which has a demographic trajectory similar to that of developed countries, emerging countries are undergoing a two-stage transition.

- Emerging countries often start out with a dependency ratio[5](in relation to the youth component). This is an undeniable advantage in the early stages of development, when the demographic transition is taking place. It creates a working-age population dividend at the beginning of the demographic transition. The increase in the working-age population allows for an expansion of production capacity. In addition, productivity increases faster than the working population thanks to foreign technologies, leading to an increase in production and per capita income. At the same time, the savings rate increases (according to Modigliani’s life cycle theory (1985)) and helps finance the investments that industry needs to develop. The labor force is growing, and as a result, pressure on wages is easing.

- As the country becomes wealthier and reaches the « middle-income » level, demographic trends may become less favorable and create vicious cycles. The accelerated aging of the population, thanks to advances in medicine and science, affects developing economies in two ways. First, the dependency ratio, which has mostly declined very rapidly, increases just as rapidly (this time due to the aging component), and the labor force quickly reaches a « peak » that will increase wages (at a constant retirement age) and restrict production capacity (at constant productivity). According to life cycle theory, agents will engage in widespread dissaving, which will make it more difficult to finance investment. These two developments will in turn weigh on incomes and development.

The accelerated aging of populations creates a temporal imbalance that conflicts with the very slow process of development: some countries thus risk becoming old before they become rich. The size of the working population is expected to decline due to accelerated aging less than 50 years after the start of the demographic transition, whereas the process has been much longer for developed countries.

Most countries (whether developed or emerging) are experiencing demographic aging in a fairly synchronized manner. However, this demographic synchronization does not correspond to a synchronization of incomes, as emerging countries are still far from reaching the standard of living of developed countries. For example, India and China’s GNI per capita represents only 3% and 11% of the GNI per capita of the United States, respectively.

Institutional dynamics

A country’s ability to avoid the trap is often contingent on its institutional development and governance. To move from one stage of development to another, the institutional balance that prevailed at the stage of economic takeoff must be able to adapt to new economic conditions and constraints, otherwise the catch-up process may quickly run out of steam. Institutional organization must be able to evolve at a certain stage of development. This involves creating new incentives for the various economic and political actors to undertake the reforms necessary for sustainable future growth. The timing and manner of the transition are therefore essential.

For example, the Chinese model of central planning geared towards investment, which trickles down through the lower levels of governance, proved extremely effective in the early stages of development but could well be the source of China’s difficulties in the years to come if the system fails to reform (see Beijing-style financial repression (II)). The recent debate on excessive local government debt, the opacity of the system, and inequalities stemming from the Chinese incentive system itself are illustrations of this and could pose new risks to the Asian giant and its ability to avoid the development trap.

It is not a question of a government rushing through reforms when growth has already slowed, but rather of having sufficient long-term vision to implement structural reforms very early in the convergence process. If a developing country hits a wall too quickly, it will not be able to avoid it. The country often slows down for a few moments before the impact. A journey must always be prepared in advance.

Conclusion

In this article, we have attempted to provide some keys to understanding the convergence process and the recent economic slowdown in certain emerging countries. However, the complexity of the phenomenon does not allow us to cover the entire spectrum of issues at play today. As a quick conclusion, it is important to bear in mind that (i) what has worked in one place and time is not necessarily applicable in another, and that (ii) we probably know more about what does not work than what does. This is why any economic orthodoxy must be used with caution when applied to development strategies.

Notes:

[1] According to the World Bank’s definition, a country successively moves into different income categories: a country is low-income if its Gross National Income (GNI) per capita is equal to or less than $1,035, middle-income if it is between $1,036 and $12,615 (with $4,085 as the dividing line between lower and upper middle-income countries), and high-income if it is above $12,616.

[2] The Solow model is a growth model in which, to simplify, per capita capital accumulation allows per capita income to converge toward a stable steady state almost automatically. Growth slows down as development progresses. This model contrasts with the Harrod-Domar model, which is much more uncertain.

[3] Notably South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore, to cite only the most striking examples.

[4] The global technological frontier represents the most advanced state of human technical knowledge (see Caselli and Coleman (2006)).

[5] The dependency ratio is the ratio of the dependent population to the working population. The dependent population corresponds to the population under the age of 15 and over the age of 65. This ratio can be broken down into its youth component (population under 15/working population) and its elderly component (population over 65/working population).