This article is a translation of an article written by Robert McCauley and Julien Pinter on VoxEU, in connection witha letter sent to the Governing Council of the ECB signed by economists including Paul de Grauwe, entitled « Banks are making billions while people struggle – the ECB needs to act (positivemoney.eu)« .

Download the PDF: abolish-reserve-remuneration-within-the-euro-system-pile-i-win-you-lose-note

- Economists suggest addressing the losses of the Eurosystem central banks by imposing large, unremunerated reserve requirements on banks.

- Their main argument is that reserve remuneration amounts to a « subsidy » for banks that should be eliminated, and that doing so would place the burden of losses on bank shareholders and borrowers.

- This article argues that the central argument for such a proposal is weak, and that this policy would in effect amount to imposing a tax on banks.

- The change in reserve remuneration (« heads you lose ») would not have been considered if interest rates had remained low and massive bond purchases had generated profits for central banks (« tails I win »).

- The potential consequences of a broad imposition of unremunerated reserve requirements on euro area banks could be significant, potentially leading to a partial relocation of banking intermediation abroad and weighing on depositors rather than on bank shareholders or borrowers.

This note offers an alternative reading of this proposal, which is to require large unremunerated reserves. We argue here that paying interest on reserves is not a subsidy to banks. On the contrary, requiring large unremunerated reserves amounts to taxing banks, as is commonly understood (Reinhart and Reinhart, 1999; Bindseil, 2014). We also argue that adopting such a policy could lead to a substantial shift of bank deposits out of the euro area and an increase in the share of domestic intermediation by lightly regulated shadow banks.

Ultimately, a further increase in unremunerated reserves must be assessed in terms of its likely impact on the euro area’s bank-dominated financial system and its implications for financial stability.

Part 1: Remunerating reserves is not asubsidy

De Grauwe and Ji (2023a) argue that remunerating central bank reserves is equivalent to « subsidizing commercial banks. » We do not share this analysis, especially at a time when reserves are abundant.

We set out our view in two parts. First, we recall how the Eurosystem came to pay interest on reserve requirements in a world where reserves were scarce. Second, we discuss the ramifications of paying interest on reserves in a world of abundant reserves following large-scale asset purchases by the Eurosystem.

Genesis: scarce reserves and remunerated reserve requirements

In normal times (in the past) in the euro area, banks requested reserves from their national central banks to meet reserve requirements, which were deliberately set above normal needs for transaction settlements. In the past, banks obtained these reserves by borrowing at the ECB’s refinancing rate against collateral. Banks thus paid interest equivalent to the refinancing rate to meet their reserve requirements.

In the initial negotiations to establish the euro, the participating central banks agreed to remunerate banks’ reserve requirements at an interest rate close to the market rate, so that holding reserve requirements would not impose a significant cost on banks. The Eurosystem opted for reserve requirements to establish a structural liquidity need in the interbank money market (see footnote 3), forcing banks to turn to the central bank for refinancing. And with the « averaging mechanism »[4], reserve requirements also served to stabilize short-term rates. Negotiators rejected the monetarist notion of creating a sharp discontinuity in the returns on reserve holdings to strengthen the link between reserves and the money supply. Negotiators also rejected the requirement for non-interest-bearing reserves to increase central bank profits.

This agreement was far from being the only plausible outcome of the euro negotiations in the 1990s. This is the message of an extremely useful book published in 2011, « The Concrete Euro, » edited by two practitioners who were present at the creation of the common currency, Paul Mercier and Francesco Papadia. In negotiations that included both future « outsiders » and future « insiders, » some major central banks opposed the principle of mandatory reserves, and only a few other central banks had experience with remunerating reserves (Galvenius and Mercier, 2011, Table 2.2).

Although reserve requirements were a common tool for central banks, they contradicted what could be called the « economic model » of two European financial centers. Neither the Bank of England, the Riksbank, Danmarks Nationalbank, nor the Benelux central banks operated with reserve requirements. The Bank of England argued that « a reserve requirement system was incompatible with market principles, » and the Luxembourg delegation was « particularly concerned that the application of a reserve requirement system would lead to a relocation of banking activities to financial centers outside the euro area » (Galvenius and Mercier, 2011)[7]. By 1990, when the US Federal Reserve (Fed) reduced reserve requirements on non-transactional accounts to zero, this practice had become widely circumvented.

The decision to require reserves and remunerate them at market rates came late, only after the list of countries joining the euro area had been clearly defined. However, the weight of the Bank of England and the Riksbank in the negotiations undoubtedly prompted the Governing Council to choose to remunerate minimum reserves as a compromise. Minimum reserves were initially set at 2% of specified liabilities, and their remuneration was initially set at the ECB’s refinancing rate, then at the deposit facility rate from October 2022 (ECB, 2023).

Today: abundant reserves and unremunerated reserve requirements?

In times of abundant reserves, banks have large amounts of « excess reserves, » in the sense that the total amount of reserves (significantly) exceeds the reserve requirements. The remuneration of these reserves has a more significant impact. It should be remembered that the Eurosystem has flooded commercial banks with excess reserves as a result of its large-scale securities purchase programs (Quantitative Easing, QE). It is these same excess reserves that Grauwe and Ji (2023a) would stop remunerating with their proposal.

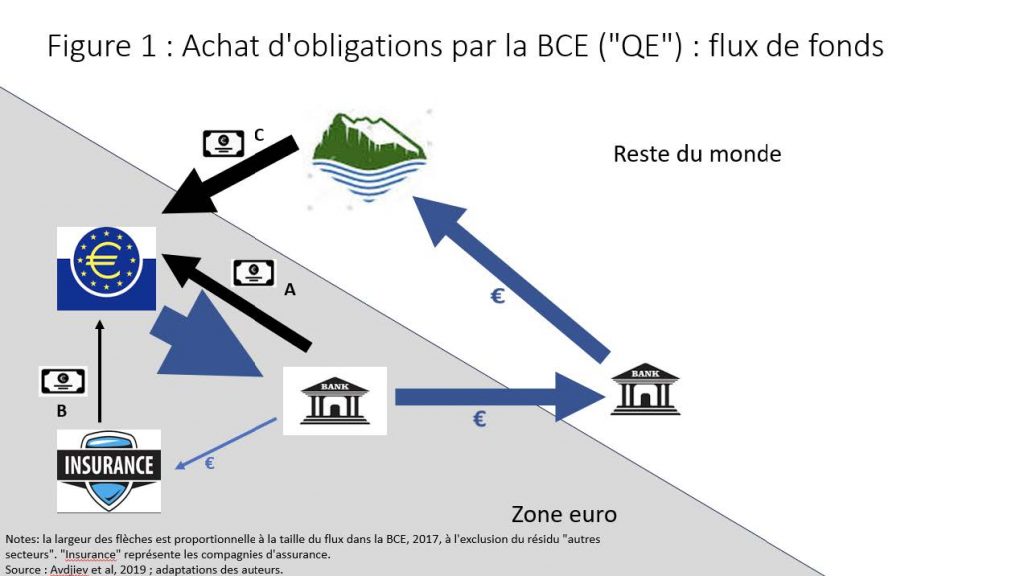

When a central bank purchases bonds, the seller may be a domestic bank or a domestic or foreign institutional investor. In Figure 1 below, the purchase transaction from a domestic bank is indicated by the code A; the purchase from a domestic institutional investor by B (where « Insurance » is a special case of an aggregate including pension funds and investment funds); and the purchase from a foreign institutional investor by C. A and C are empirically important cases (ECB, 2017), as indicated in the figure by the thickness of the black arrows. To anticipate the argument in the next section, it should be noted that non-resident institutional investors accumulated euro deposits abroad when they sold euro-denominated bonds to the Eurosystem (Avdjiev et al., 2019). Here, we focus on purchases from domestic banks, the type A transaction, to illustrate that reserve remuneration is not a subsidy to banks. But the reasoning is only strengthened when the other two cases are considered[10].

In this case, the central bank exchanged newly created « central bank reserves » for a bond held by a commercial bank. Banks only accepted this exchange if they considered it beneficial. Consider the case where a commercial bank intended to hold a bond to maturity and was considering selling it and holding the asset obtained in exchange for the same period. The bank would be willing to sell the bond if the present value of the central bank reserves, including the return in the event that short-term interest rates return to positive territory, is equal to or greater than the price of the bond.

This simplified illustration, with a representative bank agent assuming a « sell and hold » strategy[12], highlights a crucial point: banks took into account the remuneration of reserves in scenarios where interest rates would return to positive territory when selling bonds to the ECB during QE. In addition, banks set interest rates on loans and deposits based on whether or not reserves are expected to be remunerated. It should be remembered that, since its creation, the ECB has remunerated reserves at one of its key interest rates, so that only the most « imaginative » bankers would have considered the possibility that the ECB would require large levels of unremunerated reserves.

From the bank’s perspective, the imposition of large unremunerated reserves is equivalent to an unexpected loss of income due to a unilateral decision by the central bank. Compared to a government that chooses to stop paying coupons on its bonds held by banks, the imposition of large unremunerated reserves may seem much more acceptable.

This loss of income for the bank is in effect an unexpected tax levied by the central bank. Instead of considering the act of remunerating central bank reserves as a subsidy, we should therefore see the act of ceasing to remunerate central bank reserves as the imposition of an unexpected tax on banks in the euro area, in line with Bindseil (2014, chapter 8).

Let’s summarize. In the case in question, the central bank exchanged its variable-rate liability for a fixed-rate government bond held by banks. Subsequently, interest rates rose much more than banks or economists had anticipated in a central scenario at the time of the central bank’s purchases. As a result, commercial banks benefited from this swap, holding variable-rate central bank reserves instead of fixed-rate bonds. The rise in interest rates also led to financial losses for the central bank, making QEdisadvantageous in hindsight, from a narrow central bank finance perspective.

If interest rates had remained very low or even negative, the situation would have been different: central banks could have benefited from the swap over the entire period of bond holdings while still earning interest on reserves. In essence, the proposal by De Grauwe and Ji (2023a) comes at a time when adverse consequences for central bank finances have materialized and suggests that central banks use their legal power to change the nature of reserves from something resembling a variable-rate bond to something resembling a non-interest-bearing banknote. This is perfectly legal, but perhaps not very prudent.

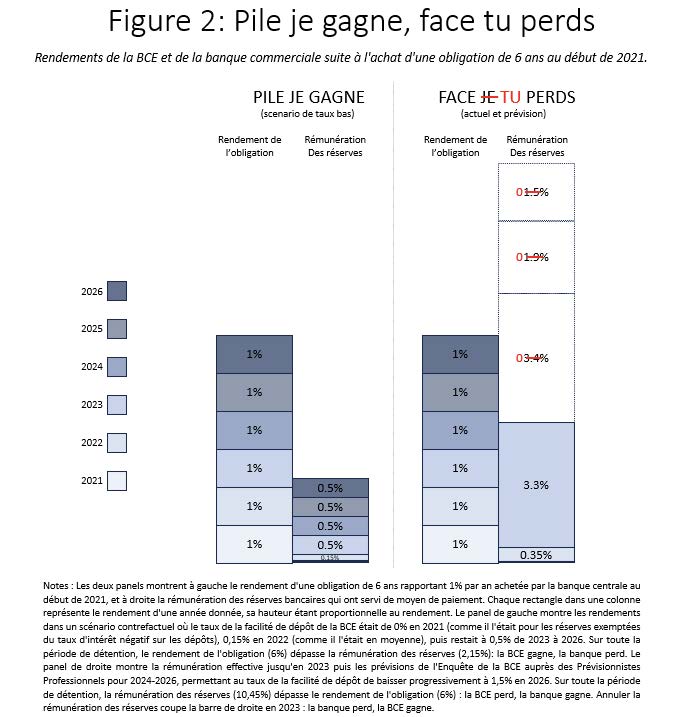

Figure 2 illustrates this « heads I win, tails you lose » approach with the case of the Eurosystem purchasing a 6-year bond yielding 1% per annum in 2021 from a bank. The left panel considers a counterfactual scenario in which the ECB deposit rate remains at low levels. The right panel considers the effective ECB deposit rate until 2023, then forecasts for 2024 to 2026 from the ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters[14]. The changes in red in the right-hand panel indicate the effect of a decision to stop paying interest on reserves from 2024: the policy removes the interest received by banks at the end of 2023. In both cases, the ECB wins and the banks lose in the right-hand panel due to the decision to stop paying interest on reserves.

Such a « heads I win, tails you lose » approach would be remembered by the banks. Pierre Wunsch, Governor of the National Bank of Belgium, warned: « We must be very careful… The next time we have to use QE, I would not like to see banks having to calculate the probabilities that this will lead to losses for central banks and speculate on the need to strengthen their reserves because we might tax them later » (Kaminska, 2023).

Part 2: The impact of the tax: who pays in theory, and will they actually pay?

Much of the debate about the requirement for large, unremunerated reserves in the euro area assumes that bank shareholders will pay. But the proposal raises the usual question about the incidence of a tax: who pays? And it also raises the usual question about how those who pay the tax will react: will they sit back and just pay the tax?

Domestic depositors would likely pay the tax

As De Grauwe and Ji (2023a,b) point out, stopping the remuneration of bank reserves will lead to an immediate reduction in bank revenues. They note that this could mean that « 12% of the balance sheet of these credit institutions would be tied up in non-interest-bearing assets » (De Grauwe and Ji, 2023b). The leading European banking analysts at the rating agency Standard and Poor’s conclude: « For euro area banks as a whole, and all other things being equal, we estimate that a one percentage point increase in unremunerated MRR [(minimum reserve requirements)] could lead to an immediate gross reduction in pre-tax profits of 3.3% » (Charnay and Hollegien, 2023). A 10 percentage point increase in reserve requirements would therefore reduce the profits of eurozone commercial banks by a third. But the story would not end there.

In all likelihood, banks would then seek to restore their net interest margin and maintain their profitability. To do so, banks could either raise the rates at which they lend or lower the rates at which they pay on deposits. De Grauwe and Ji (2023a,b) mention the first possibility, but not the second. Admittedly, the former would be in line with the ECB’s strategy to combat inflation. However, the latter would run counter to this strategy. Lower deposit rates would discourage rather than encourage savings, and would therefore have the opposite effect on consumption (Kwapil, 2023).

The general answer to the question of whether bank depositors, borrowers, or shareholders would pay the tax depends, among other things, on the elasticity of demand for deposits relative to the elasticity of demand for loans (Reinhart and Reinhart, 1999). In this case, however, the experience of the Eurodollar market suggests a fairly clear answer to the question of who would pay the tax.

The experience of the Eurodollar market from the 1970s until the Fed reduced the reserve requirement on domestic certificates of deposit to zero in 1990 seems to indicate that domestic depositors pay[15]. In other words, immobile domestic depositors (those with few or no alternatives) pay the tax imposed by reserve requirements, not shareholders or bank borrowers.

In response to the Fed’s imposition of unremunerated reserve requirements on non-transactional accounts, US and foreign banks engaged in arbitrage in the dollar markets in London and New York to equalize the total costs of Eurodollar deposits and large domestic certificates of deposit. As a result, the 3-month dollar Libor generally exceeded the yields on US certificates of deposit by the sum of the cost of the reserve requirement plus the cost of deposit insurance (Kreicher, 1982; McCauley and Seth, 1992). Depositors who insisted on depositing with a bank in the United States rather than in London or the Caribbean paid for this privilege.

Would euro deposits relocate to London?

Would euro area bank depositors remain passive in the face of large unremunerated reserve requirements? Or would they move their euro deposits to banks outside the euro area? What would prevent ING Ltd in London from marketing euro-denominated deposits on the Internet to households and businesses in the euro area?

It should be noted that such deposits are not included in the aggregate of euro area deposits subject to reserve requirements, which are now unremunerated (ECB, 2002), and that a very large offshore euro deposit market already exists and does not need to be created[16]. Depositors could demand a higher return without taking any currency risk and with only a negligible country risk[17]. At an interest rate of 4% and with a reserve requirement ratio (unremunerated) of 15% (or 10%), ING could probably offer its Internet customers up to 60 (or 40) basis points more on a euro deposit in the United Kingdom than on the same deposit made in the euro area[18].

The popularity of online banking among Europeans may not have reached the level seen among Californians, who opted en masse for rapid bank withdrawals in March 2023, but the latter could learn quickly with sufficiently large incentives. In addition to this direct marketing of offshore deposits, what would prevent euro SICAVs in France and euro money market funds in Luxembourg from losing their domestic bias, as US prime money market mutual funds did a generation or two ago (Baba et al, 2009)?

60 or 40 basis points is not insignificant. After the Dodd-Frank Act expanded the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s charge base from just 8 to 10 basis points, half a trillion dollars in US deposits moved from offshore to onshore in a matter of months in 2011-12 (Kreicher et al., 2014; McCauley and McGuire, 2014). A similar response to the larger tax gap of a 15% or 10% unremunerated reserve requirement in the euro area could perhaps induce €3-4 trillion of the €15 trillion in reserveable deposits in the euro area to move to London or other centers. As a result, the increase in net revenues for euro area central banks—the amount of tax collected—would be less than projections that assume euro area depositors would remain passive.

Significant damage could also be inflicted on financial stability. A spread of 60 or 40 basis points would favor not only offshore euro deposits but also non-bank financial intermediation in the eurozone. Banks could lose business to shadow banking competitors with often limited capital and no lender of last resort. Although large unremunerated reserve requirements may be intended to penalize banks, bank depositors and the public interest in financial stability could turn out to be the big losers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, reserve remuneration does not suffer from a « lack of economic justification, » particularly when demand for reserves is satisfied and the marginal liquidity services provided by reserves are therefore virtually nil. When a central bank unexpectedly stops paying interest on reserves after exchanging them for long-term bonds, it imposes a new tax on banks to increase its profits. Any potential benefits of future central bank bond-buying programs (such as QE) would call for caution before taking such a step.

The expected improvement in euro area central bank revenues from large unremunerated reserves is probably overestimated. High-income firms and households could potentially shift their euro deposits to jurisdictions on the periphery of the euro area that do not present significant legal or country risks.

There may be an optimal level of unremunerated reserve requirements that would be positive from the perspective of maximizing economic welfare. This level should take into account not only central bank profits, but also the fiscal effects on the structure and competitiveness of the euro area banking system. The analysis by De Grauwe and Ji (2023b) does not elaborate further on these issues. We believe that further consideration of the optimal level of (un)remunerated reserves is important before considering a policy change in this area.

Article co-authored by Julien Pinter and Robert N. McCauley

[2] For July 2023, see https://data.ecb.europa.eu/publications/ecbeurosystem-policy-and-exchange-rates/3030611.

[3] Banks need a minimum amount of liquidity to ensure their payments (especially to other banks) each day. Reserve requirements are set at a level above this minimum, thus « forcing » banks to have an additional cushion of liquidity. It is important to note that countries such as China and other emerging economies still use reserve requirements as a monetary policy tool, adjusting either their level or their remuneration. The study by Reinhart and Reinhart (1999) cited above discusses these cases. In practice, as we argue here, adjusting the level of remuneration on reserve requirements amounts to taxing banks more (or less), which, as Reinhart and Reinhart (1999) show, then impacts banks’ deposit or lending rates (and sometimes their margins as well).

[4]Or « averaging provision » in English, a system whereby banks must meet reserve requirements on average over a given period.

[5] Three central banks had experience with reserve remuneration. The Bank of Portugal remunerated reserve requirements at market rates, while the Bank of Italy and the Central Bank of Ireland partially remunerated reserve requirements.

[6] Keynes interpreted the (low) cost of reserve requirements as a fee for banks’ participation in a payment system managed by a central bank: « The custom of requiring banks to hold larger reserves than they strictly require for till money and for clearing purposes is a means of making them contribute to the expenses which the central bank incurs for the maintenance of the currency » (Bindseil, 2014, p. 107).

[7] As financial centers, London and Luxembourg benefited from the transfer of deposits in dollars and Deutsche Marks, respectively.

[8] It was then reduced to zero in July 2023, with the aim of « reducing the amount of interest payable by the central bank. » When asked whether this policy was intended to limit losses on the Eurosystem’s balance sheet, C. Lagarde did not respond in the negative.

[9] Currently, these reserves can be deposited with the Eurosystem’s deposit facility to earn the deposit facility rate.

[10] In any case, only commercial banks in the euro area are able to hold central bank reserves, the Eurosystem’s means of payment.

[11] We are disregarding the liquidity service of reserves here because, with abundant reserves (as was quickly the case after the launch of QE), the value of this liquidity service of reserves becomes zero (Woodford, 2012, p. 51).

[12] Avdjiev et al. (2023) explain that the seller has four options for disposing of or retaining the funds received from the purchasing central bank, one of which is « sell and hold. » Our reasoning extends to all other cases beyond « sell and hold, » insofar as the ultimate holder of central bank reserves takes into account the remuneration of central bank reserves when exchanging another asset for reserves.

[13] This does not take into account the positive financial effects of QE on public finances resulting from lower interest rates on bonds that have not been purchased by the central bank, or from its positive impact on the economy and therefore on tax revenues.

[14] For periods for which we have no SPF forecasts (second half of 2025 and 2026), we assume that the deposit facility rate will gradually decline to 1.5% and remain at that level for 2026.

[15] This section and the next are based on McCauley (2023a) and McCauley (2023b).

[16] London is a very important international banking center (Demski et al., 2022). Banks in London report €1.7 trillion in euro-denominated liabilities, mainly to non-banks.

[17] If ING UK holds the corresponding asset as a deposit at ING Amsterdam, the latter’s liability would be reserveable (ECB, 2002). However, ING could simply transfer loans from Amsterdam to London. If such assets were extraordinarily included in the reserve base, as was the case in the United States, then ING could find a solution by registering newly created loans in London. In the case of the United States, the Eurodollar reserve requirement also included loans granted by foreign branches of US-chartered banks to US residents. However, this extraterritorial scope of the reserve requirement did not apply to banks without a US charter, which gave foreign banks a competitive advantage in the market for loans to US companies (McCauley and Seth, 1992).

[18] That is, .04 X .15 = .006 or .04 X .10 = .004.