-

While signs of a slowdown in China are cause for concern, their interpretation should not focus on the short-term repercussions, which are fairly limited, but rather on the medium to long term.

-

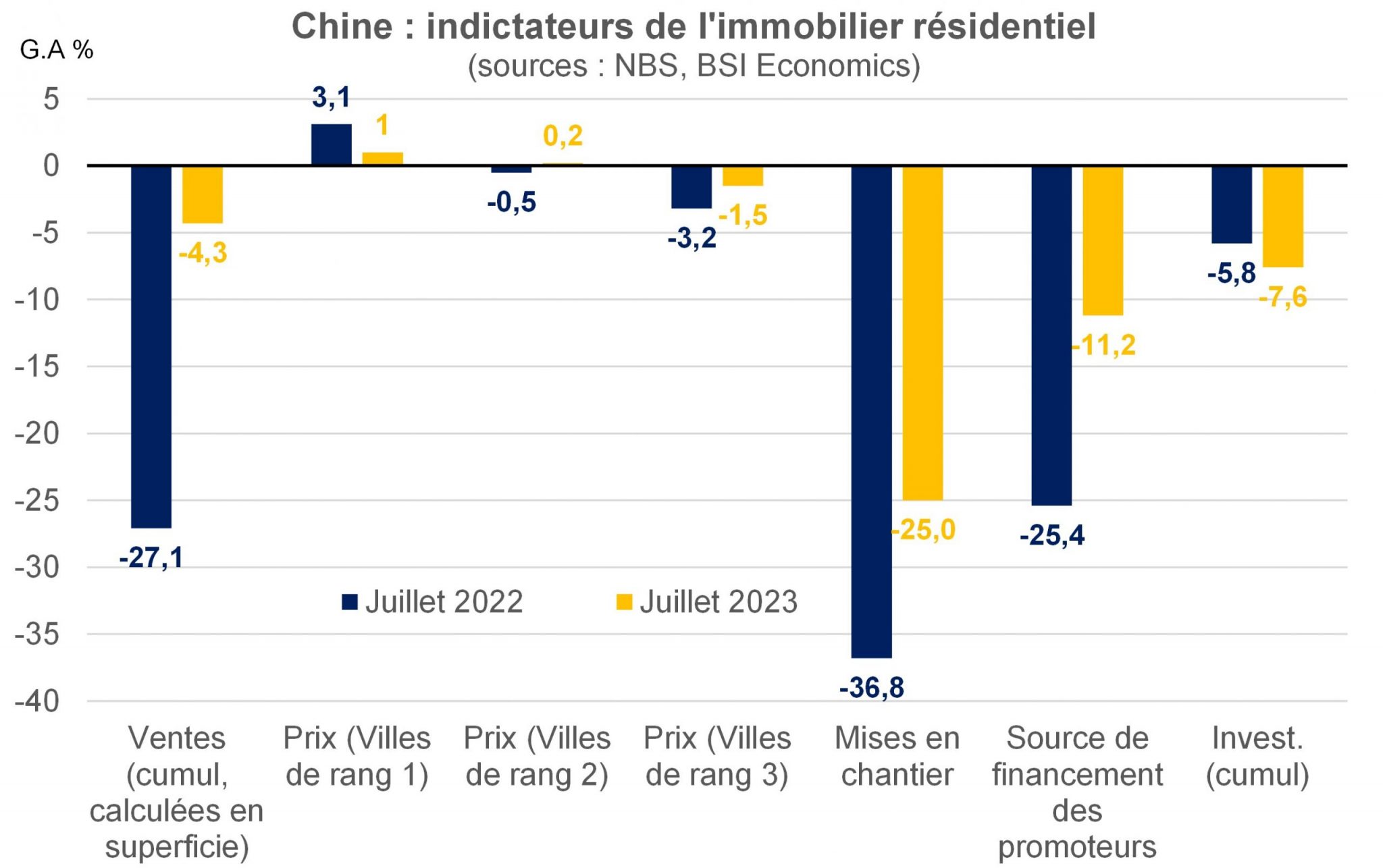

Signals from the real estate sector and recent measures taken by the authorities reveal deeper imbalances and raise questions about the authorities’ room for maneuver, whether monetary or fiscal.

-

Reduced room for maneuver is not insignificant for a country aiming to converge towards a more sustainable growth model. China will need powerful financial levers to achieve its ambitious goals.

-

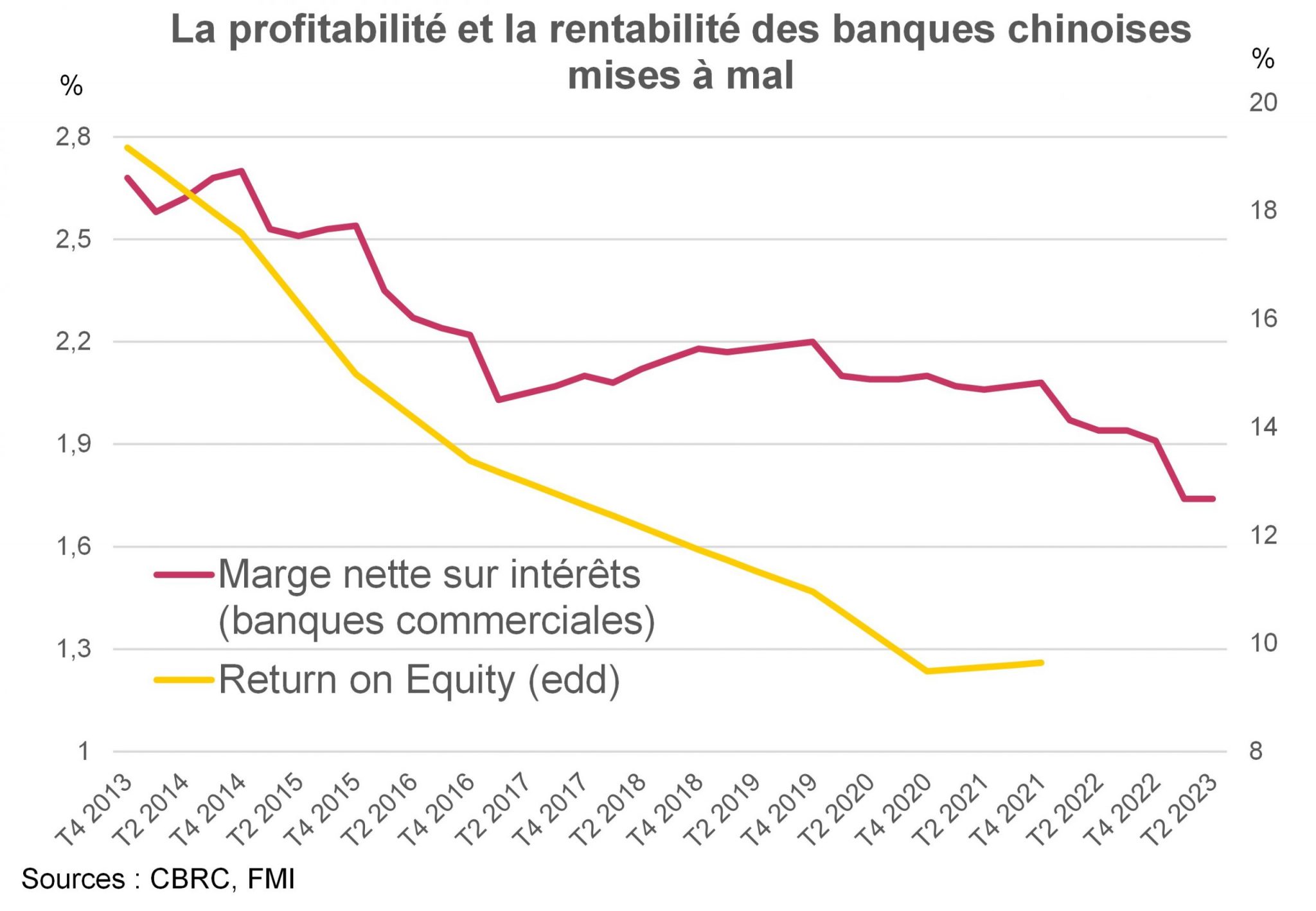

Monetary support is constrained by conflicts of interest at the central bank level: providing more liquidity to a system plagued by endemic debt, avoiding further depreciation of the yuan, and preserving the profitability of the banking sector.

-

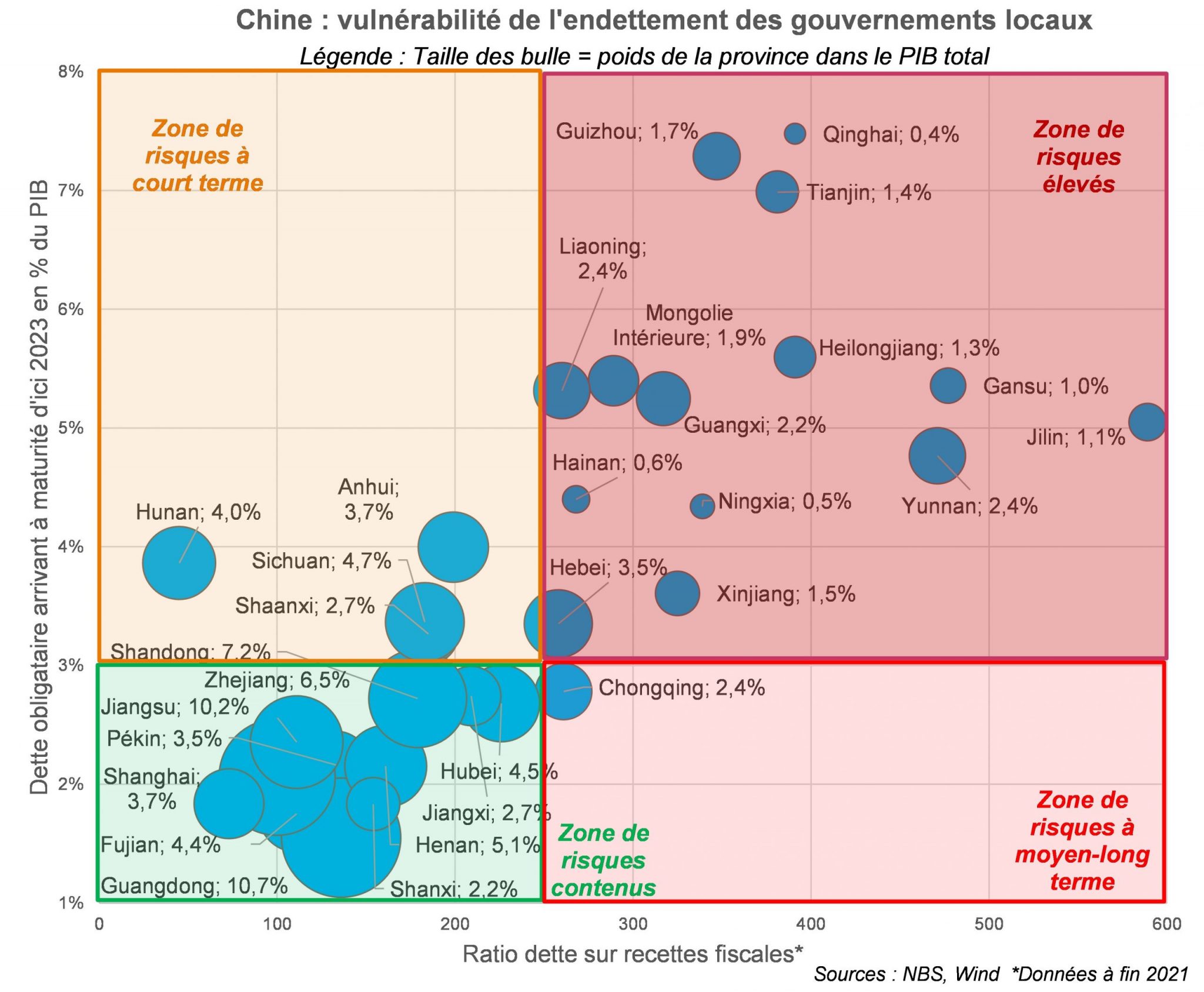

The solvency of several local governments is being called into question, and their growing financial difficulties also raise the question of their ability to continue to drive economic growth in the medium to long term.

Monetary margins under pressure

Prior to the announcements in July-August 2023, most of the support measures in China were monetary in nature, with the central bank (PBoC) not only lowering several benchmark interest rates (reserve requirements[6], 1-year and 5-year Loan Prime Rates[7], Medium Long Term Facility rate – MLT), but also injected significant liquidity into the banking market via the MLF market. The PBoC is even considering offering a specific line of loans with favorable interest rates and maturities to facilitate repayments by real estate developers and LGFVs[9](see next section). However, the PBoC’s room for maneuver is limited. Indeed, it cannot bring itself to provide more massive support given the current context and the structural specificities of the Chinese economy:

- Conflict of interest: since the late 2010s, strengthening financial stability has been one of China’s priority objectives. Lowering interest rates would encourage an increase in debt, which is already endemic (corporate and household debt will reach 246.7% of GDP by the end of 2022), thereby compromising financial stability.

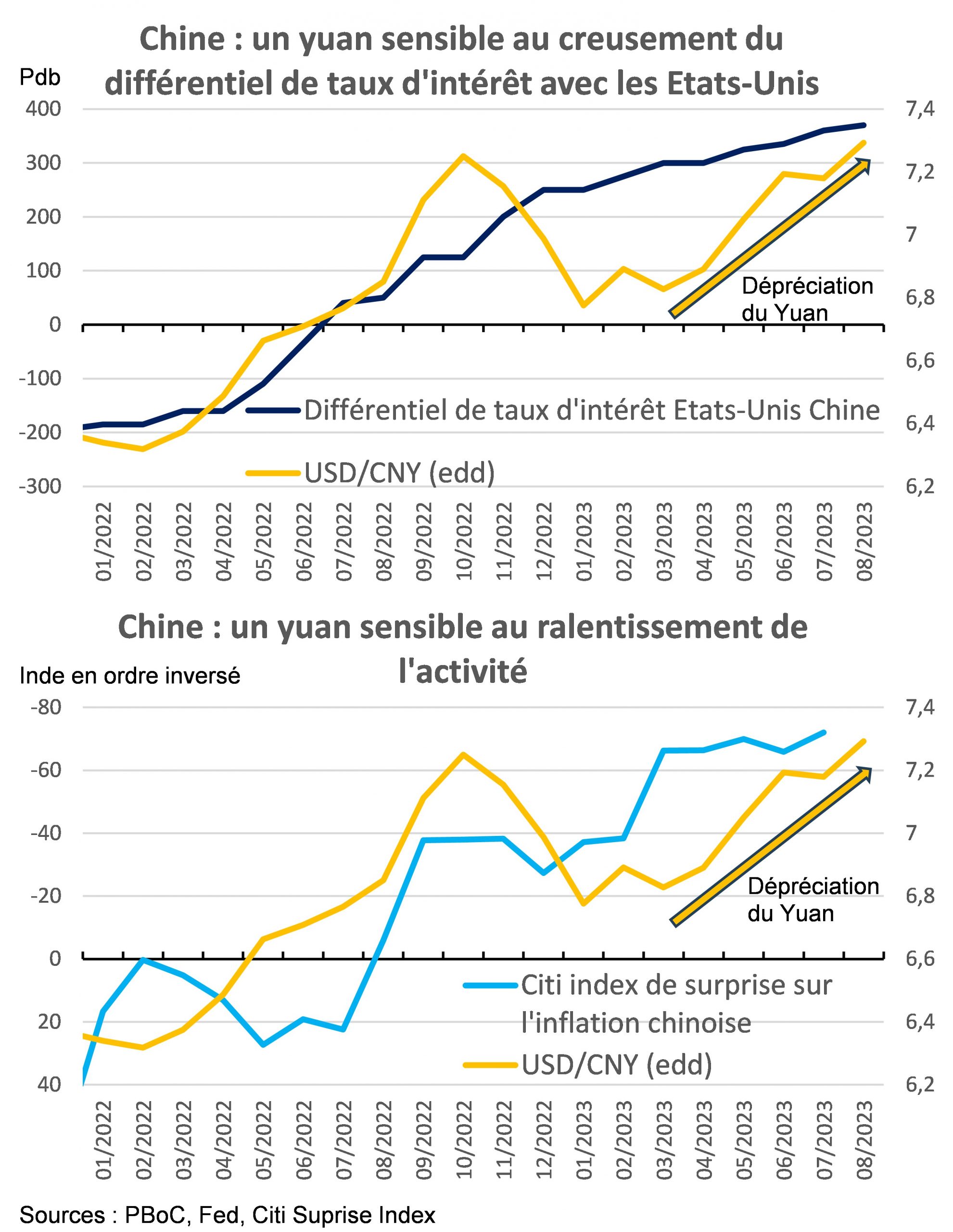

- Pressure on the yuan: while the rest of the world is raising its key interest rates, the PBoC is taking the opposite approach. This is resulting in a growing interest rate differential between China and the United States, making Chinese investments relatively less attractive. The more accommodative the PBoC is, the higher the risk of yuan depreciation (see chart below), even though the Chinese currency is already weakened by the economic situation. As a reminder, the country recorded net capital outflows of USD 459.7 billion in 2022, mainly due to this interest rate differential and economic performance that fell short of expectations.

- Weakening of banks: the effect of a rate cut has an ambiguous impact on the banking sector. While it would certainly reduce the cost of financing their liabilities, interest margins would narrow,and asset yields would tend to decline in a low interest rate environment. Furthermore, given the situation in the real estate market, it seems unlikely that the PBoC’s measures will stimulate household demand for credit.

These short-term monetary dilemmas are also problematic in the medium to long term. If China wants to change its growth model by increasing the weight of private consumption, particularly through reforms (rollout of the « Common Prosperity » and « Dual Circulation » strategies, see Evelyne Banh’s article on BSI Economics on this subject), the question of how to finance this transition currently has little or no concrete answer. It would appear that the usual lever of bank credit will no longer be available to the same extent, which could lead to a revision of China’s ambitions.

The looming shadow of local government debt

Thefragility of local governments (LG) in China has been a recurring theme for nearly a decade. Local governments are given very ambitious growth targets, which are generally out of step with their financing capabilities, leading them to take on debt. To achieve their growth targets, they rely on structures known as LGFVs to take on more debt without it being recorded in their official balance sheets. By incorporating these opaque financing methods, local government debt would increase by 58 points and reach a very high level of 94% of GDP in 2022, according to IMF estimates.

Closely linked to fluctuations in the real estate market, local government revenues have fallen sharply in line with the collapse in property prices. In this context, the sustainability of their debt is deteriorating in several respects. First, significant amounts of bond debt maturing by the end of 2023 increase the refinancing risk for several local governments. In addition, the implicit guarantee between local governments and their LGFVs exposes them to significant losses, as LGFVs face increasing difficulties in accessing sources of financing. These LGFVs also face refinancing risks in 2023.

The chart below maps the level of risk incurred according to three criteria:

- The weight of the provinces in GDP: the higher their weight, the greater the systemic importance of the province. Financial difficulties for the local governments of the most systemic provinces would pose two problems: the high cost of a « bailout » by the central authorities on the one hand, and reduced capacity to carry out projects on the other, which would affect the country’s overall growth.

- The ratio of official debt to tax revenue: the higher this ratio, the more the solvency of local public finances is impaired, as the amount of revenue generated appears insufficient in relation to debt repayment challenges (here, official debt does not take into account exposure to LGFVs);

- Local government bond debt maturing in 2023 expressed as a percentage of the province’s GDP: the larger this share of total bond debt, the greater the refinancing risk and the greater the pressure on public finances in the short term.

In the chart, the threshold for the debt-to-tax revenue ratio corresponds to the average ratio for local governments in China (250%). Although this threshold is not based on a threshold proposed in academic literature, observation of debt data in emerging countries[16](at the central government level) shows that a ratio exceeding 250-300% generally precedes periods of severe pressure on the sovereign. The threshold for the weight of debt repayments in GDP was set arbitrarily, based on the distribution of local government data.

Interpretations of this graph:

- Contained risk zone(green, bottom left): most of the provinces with the highest weight in GDP (Guangdong, Zhejiang, Shandong, Henan) are located in this zone, which has a total of 11 provinces. In this zone, the ratio of local government debt to tax revenue is below the average of 250%, implying a relatively less deteriorated public finance structure. In addition, the refinancing risk appears to be lower, with the amount of bond debt maturing in 2023 less than 3% of GDP.

- Short-term risk zone ( light orange, top left): Four local governments are located in this zone, including Sichuan and Hunan, which each have significant economic weight (more than 4% of China’s total GDP) and therefore present a systemic risk. The risks in this zone are more short-term, due to a large amount of repayments due in 2023 (more than 3% of GDP). The degree of risk appears limited. On the other hand, their medium- to long-term fragility appears limited, given that their debt-to-tax revenue ratios are among the lowest.

- Medium- to long-term risk areas ( light red, bottom right): One local government appears in this area: Chongqing, whose weight in China’s total GDP is not particularly high (2.4%). While its refinancing risk is low, its level of vulnerability is nevertheless significant in the medium to long term, given its debt-to-revenue ratio.

- High-risk areas ( dark red, top right): 14 local governments appear to have higher levels of fragility in both the short and medium term. Within this population, the level of risk is more contained in three provinces (Hainan, Hebei, Xinjiang) but appears to be particularly significant in six others (Gansu, Qinghai, Guizhou, Jilin, Tianjin, and Yunnan).

A similar exercise carried out on the amount of bond debt maturing in the period 2024-2025 as a percentage of GDP highlights that some regions are subject to high refinancing risks during this period (Chongqing, Beijing), while others see this risk decreasing (Anhui, Hebei, Sichuan, and Xinjiang).

The issue of the sustainability of local government finances is central in China. Despite the real estate crisis, local governments still play a pivotal role in driving economic growth andhave been authorized to issue new bonds[17]to finance their economic support policies. Their financial difficulties could push some to use the funds raised to repay their direct or even indirect debt (implicit guarantees to LGFVs, public banks, and even developers), to the detriment of financing economic activity and the strategic objectives of « Common Prosperity. »

The real estate crisis may be just a foretaste of a private debt crisis and a local government debt crisis. The signs of a slowdown observed in recent months seem to point to likely difficulties ahead.

After financing its growth through debt for several years, China may therefore find itself with significantly reduced room for maneuver in the future. It will be interesting to see how China manages, or fails, to address its many imbalances without having to scale back its ambitions. In any case, China will need to find new sources of financing as it seeks a more sustainable growth model.

[1]Exports contracted by an average of 3.9% year-on-year over the first seven months of 2023 (and imports by 7.1%).

[2]The publication of this unemployment data has also been suspended by the authorities, citing « methodological issues. »

[3]Forecasters may be more vigilant than before about the repetition of negative signals in China since 2022, when the growth target set by the authorities was not met, a first since China began communicating growth targets.

[4]The main fiscal measures concern private consumption (mainly by facilitating the purchase of electric vehicles), private companies (increased financial support for the tech and infrastructure sectors and regulatory provisions aligned with those of the public sector, particularly for the financing of real estate projects) and the real estate sector (measures to facilitate the purchase of second homes in major cities for households that already have mortgages). However, doubts remain about the effectiveness of these measures, which are considered insufficient and too timid.

[5]Given the impact of lockdown measures in Q4 2022, several indicators are expected to rebound strongly in annual terms in Q4 2023: retail sales, industrial production, trade, etc.

[6]In China, there are several interest rates linked to reserve requirements (RRRs). RRRs are key monetary policy tools in China for curbing the supply of liquidity in the economy and influencing the value of the yuan.

[7]The 1-year LPR serves as the benchmark rate for customers with a very low probability of default, while the 5-year LPR serves as the benchmark for mortgages.

[8]LGFVs are financing vehicles that Chinese local governments have relied heavily on since the mid-1990s to finance infrastructure projects. These opaque structures have become particularly indebted in recent years, and the sustainability of their debt has been called into question since the mid-2010s. This note from the French Treasury provides an overview of the issues related to LGFVs.

[9]The chart below shows a correlation since 2022 between the depreciation of the yuan (in yellow) and poor economic performance, as measured by the economic surprises index for inflation (in blue, in reverse order on the chart). The intuition is as follows: when the surprise index deteriorates (increases on the graph), inflation figures underperform relative to expectations, revealing disappointing economic activity. This is perceived as a source of risk by investors, who tend to turn away from the Chinese market, betting on a decline in the value of the yuan.

[10]Deposit rates are particularly low in China, notably with the aim of discouraging households from over-saving and thus stimulating private consumption.

[11]The challenges of local government debt in China were the subject ofa previous BSI Economics article.

[12]Even after central government budget transfers (45% of local government revenues and nearly 8% of GDP in 2022).

[13]Their official debt rose from 21% of GDP in 2015 to 29% in 2022, according to the IMF.

[14]LGFVs benefit from an implicit guarantee from their local government and also rely on real estate assets as collateral to raise debt and thus directly finance projects, mainly infrastructure projects.

[15]Land sales accounted for nearly 45% of total local government revenues in 2020.

[16]Observation made in around 30 emerging countries, those with recent episodes of sovereign stress (Argentina, Angola, Brazil, Congo, Egypt, Ecuador, Ghana, Jordan, Laos, Mongolia, El Salvador, Senegal, Sri Lanka, Tunisia, Zambia, Zimbabwe) and countries where sovereign risk appears to be low or moderate (Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Bulgaria, China, Chile, Georgia, India, Indonesia, Morocco, Namibia, Mexico, Peru, Poland, Romania, Turkey).

[17]CNY 4,803 billion (3.3% of GDP) in Special Purpose Bonds were raised by local governments in 2022.