Usefulness of the article :In addition to commodity prices, inflation is influenced by many factors, which are useful to identify in order to track its evolution. In Switzerland, there is a strong positive correlation between the central bank’s key interest rate and sovereign bond yields on the one hand, and between the latter and fixed mortgage rates on the other. Accurate forecasting of monetary policy is therefore essential for investors and households to anticipate changes in these key interest rates.

French version:

English version:

Abstract :

- In Switzerland, inflation fluctuates at a rate close to that of unit labor costs over the long term. A UBS survey, which suggests that wage increases for 2023 will be +2.2%[1] compared with inflation of +2.8% in 2022, could be a sign of a potential slowdown in wage growth.

- At least two factors are likely to exert downward pressure on inflation in the medium term: international competition and, above all, the nominal appreciation of the Swiss franc, which has averaged 2% per year over the last 30 years.

- Inflation is expected to fall below the 2% threshold in 2024, meaning that the Swiss National Bank (SNB) key interest rate could fall between now and 2025 from its peak at the end of 2023.

- Lower-than-expected inflation would mean lower key interest rates and therefore lower bond yields.

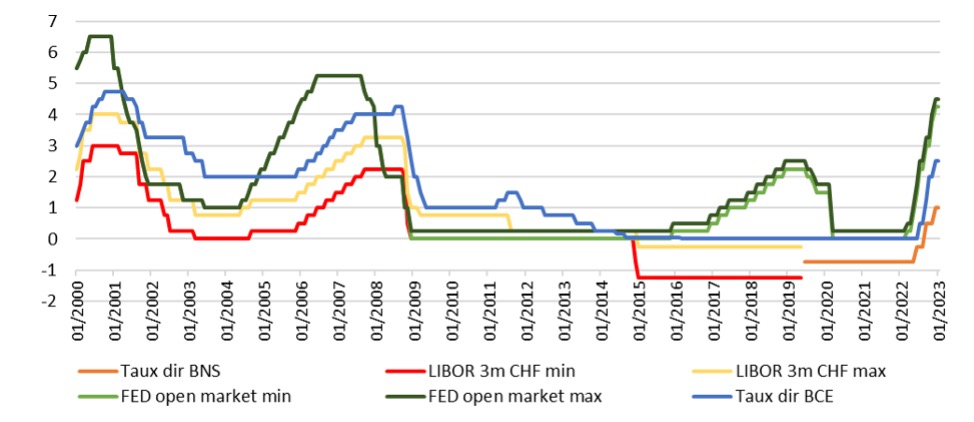

Switzerland saw the imported inflation shocks of 2022 greatly mitigated by the appreciation of its currency, which sometimes acts as a safe haven. Inflation there is significantly lower than in the eurozone and the United States, both in 2022 (2.8%) and over the long term: since 2002, it has averaged 0.5% in Switzerland, compared with 2% in the eurozone and 2.4% in the United States. In the current inflationary environment, the SNB has raised its key interest rate in line with the European Central Bank (ECB), but to a lesser extent, with the key rate standing at 1.5% in Switzerland compared with 3.5% in the eurozone in March.

The case of Credit Suisse, which has been absorbed by UBS, is linked to governance issues specific to this bank, which should not in themselves lead to a change in the SNB’s monetary policy.

What pressures will be exerted on prices in Switzerland in the medium term? What implications will monetary policy have on sovereign yields and mortgage rates? What macroeconomic scenario do investors’ expectations regarding sovereign yields and monetary policy correspond to?

1) The specific characteristics of the Swiss economy favoring low inflation

With thefifth-highest GDP per capita in the world andseventh-highest in terms of purchasing power parity in 2021, the Swiss economy is characterized first and foremost by its high standard of living, supported by intensive use of labor (80% employment rate, more hours worked per year than in France due to fewer holidays). Labor productivity is high in industry (20% of the country’s added value).

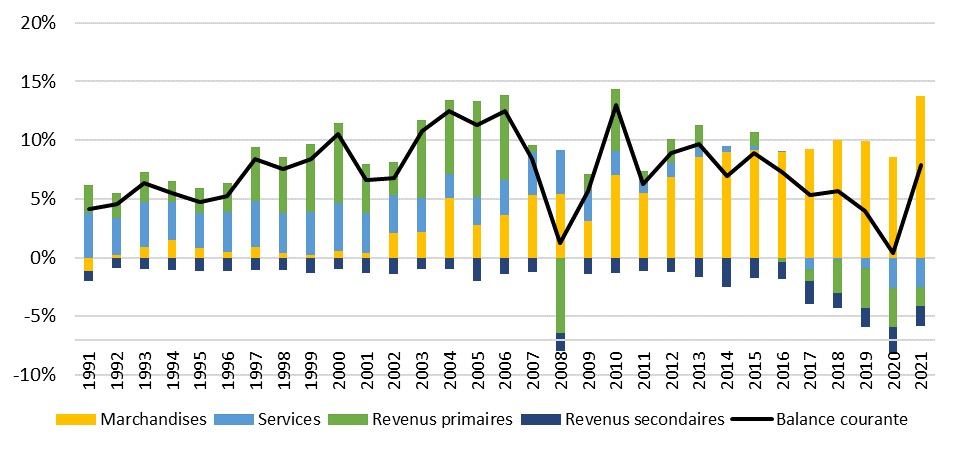

Switzerland therefore has a large current account surplus (6.5% of GDP on average over the last 10 years), driven by the pharmaceutical, chemical, watchmaking, and commodity trading sectors. The Swiss economy also benefits from an efficient labor market (structural unemployment rate below 5% according to the ILO), a continuing education system that facilitates integration into this market, and an ecosystem conducive to innovation, in addition to R&D spending representing 3.2% of GDP in 2019.

Switzerland’s strong current account surplus and low inflation rate contribute structurally to the nominal appreciation of its currency, averaging 2% per year across all currencies. The appreciation of the Swiss franc in turn puts downward pressure on prices. In 2015, the removal of the euro-Swiss franc exchange rate floor led to a sharp appreciation of the Swiss franc and slight deflation in the Swiss economy. The Swiss National Bank (SNB) then intervened in the foreign exchange market and kept short-term interest rates below those in the eurozone in order to prevent its currency from appreciating too rapidly.

As one of the developed countries, along with Japan, that fought deflation during the period 2015-2019, Switzerland was well positioned to absorb the inflationary shocks of 2021-2022 linked to oil and food commodity prices, supply chain bottlenecks, and fiscal policy related to the COVID-19 pandemic. In Switzerland, economic support measures, which were mainly short-term with the exception of increased funding for applied research, accounted for 2.2% of GDP in 2020, but were not followed by a separate stimulus plan in the strict sense, unlike in the eurozone and the United States.

2) Inflation is expected to fall rapidly below the 2% threshold in Switzerland, driven by the nominal appreciation of its currency and international competition

In Switzerland, the increase in the general price level as measured by the consumer price index (CPI) stood at +2.8% in 2022.

However, several factors will exert structural downward pressure on inflation over the next 10 years. Between 1994 and 2022, the Swiss franc appreciated nominally by 81%, or 2% per year on average, with this average annual rate persisting over the last 10 years. While the peaks in the Swiss franc’s appreciation, observed for example against the euro, were driven by financial factors or the currency’s role as a safe haven, it is clear that they were followed by only partial corrections.

In fact, one key factor is putting pressure on the Swiss franc to appreciate in the medium term: Switzerland’s current account surplus, which implies a structural excess demand for Swiss francs for current transactions (purchases of goods and services in Switzerland and income flows). Switzerland’s current account surplus has averaged 6.5% of GDP over the past 10 years.

Chart: Swiss current account balance and its components according to the SNB, as a percentage of GDP

After an exceptional deterioration at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Switzerland’s current account surplus rebounded to 8 points of GDP in 2021 and is not expected to deteriorate in 2022, according to data for the first three quarters. For the coming years, it is reasonable to expect a substantial current account surplus in Switzerland, with the massive goods balance surplus being driven by two sectors where demand is relatively insensitive to prices: the pharmaceutical industry and commodity trading. The current account surplus is likely to contribute to the nominal appreciation of the Swiss franc, which is expected to continue and put downward pressure on import prices as long as there is no substantial real appreciation of the currency.

In addition, international competition is likely to remain high and contribute to downward pressure on producer prices in sectors exposed to it. Furthermore, in the short term, the removal of bottlenecks linked to health restrictions should increase the supply of available goods and thus contribute to a fall in prices, particularly for imports, according to UBS, which also expects energy prices to stabilize.

Finally, wages account for a significant share of Switzerland’s GDP, ranging from 54% to 60% over the period 1995-2021. They therefore have a significant impact on the cost of goods and services produced in Switzerland. On average, labor costs per unit of output grew by 0.4% per year over the period 1991-2021, according to the OECD, which is a slow pace by international standards and slightly lower than inflation (+0.9%).

According to a UBS survey, the peak inflation rate of 2.8% in 2022 would only lead to an average wage increase of 2.2% in 2023. While this figure has yet to be confirmed by official data, it does not suggest any acceleration in wage growth. It should also be noted that the share of wages in GDP was already at a high point in 2021 (59.2%), so it seems unlikely that this share will increase significantly in the coming years.

Given the trajectory of the main determinants of inflation in Switzerland, it is likely that inflation will quickly (in 2024) fall below the +2% threshold and remain there for the long term, barring any new shocks (see Part 3).

3) Inflation could be lower than expected, leading to a potential decline in 10-year rates

In the short term, even if inflation falls below 2% at the end of 2023 or beginning of 2024, it will remain subject to a possible rebound linked to imports from Switzerland’s major partners (notably the eurozone and the United States), where inflation is higher. In particular, if the Swiss franc were to depreciate temporarily from its peak in December 2022, for example due to fears about financial stability, which appear to have been brought under control at this stage, import prices would rise. Therefore, in order to avoid a depreciation of the Swiss franc, it is likely that the SNB will not set its key interest rate in 2023 at a level significantly lower than that of the ECB.

On the other hand, once inflation has fallen in Switzerland and eased in the eurozone and the United States (in 2024/2025), the SNB will no longer have any reason not to widen the gap between its key interest rate and that of the ECB. In particular, it will be able to set key interest rates significantly lower than those of the ECB without fear of a sharp shock from imported inflation. In addition, growth in the eurozone and the United States is expected to remain below its potential until at least 2024, which should slow down growth in Switzerland, which is mainly determined by foreign trade.

Therefore, given its objective of supporting economic activity, the SNB could reduce its key interest rates from the end of 2024 onwards, barring a new inflationary shock.

Chart: Key interest rates in Switzerland, the eurozone, and the United States, in %

Source: SNB

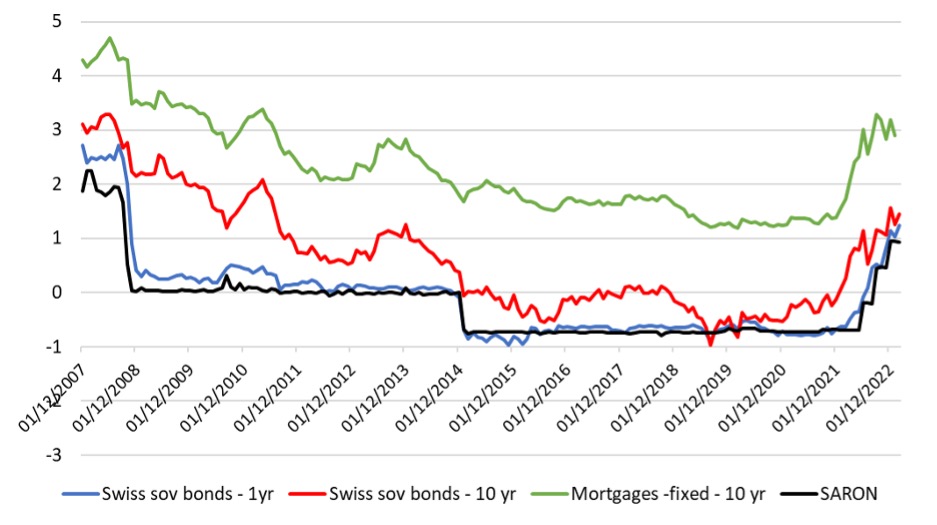

Sovereign bond yields are closely linked to the key interest rates set by the national central bank[2], which partly determine short-term interest rates. Unless there is a sharp increase in the supply of foreign financing, sovereign bond yields are therefore set at a level that reflects risk premiums (compensating in particular for the risk of illiquidity and default at maturity) relative to the anticipated key interest rates. In the case of Switzerland, where public finances are particularly healthy thanks to effective debt-braking mechanisms (public debt fell to 40% of GDP at the end of 2022), the gap between sovereign bond yields and the anticipated SNB key interest rate is particularly narrow.

At a time when key interest rates were expected to remain slightly negative (2019), 10-year sovereign bond yields stood at -0.49%, 26 basis points above the SNB’s key interest rate (-0.75%).

In February, 10-year sovereign bond yields stood at 1.45%. They included monetary policy expectations and a risk premium. Bond yields could correspond to (i) a risk premium at the level observed in 2019 (26 basis points) and an average expected policy rate for the next 10 years of 1.2%, or (ii) a higher risk premium combined with a lower expected policy rate than in scenario (i) above. However, a significant increase in this risk premium cannot be considered a central scenario given the strength of Switzerland’s public finances. Furthermore, if the average key interest rate were to be 1.2% over the next 10 years, it would be at the high end of the range of macroeconomic scenarios that can be anticipated. If key interest rates were to be lower than anticipated, 10-year sovereign bond yields could decline.

If sovereign bond yields were to be excessively high, the average interest rates on new mortgage loans, which are closely linked to them (see green curve in the chart below), would also be high. Fixed 10-year interest rates on mortgages granted in January 2023 averaged 2.9%, with a premium over sovereign yields at that horizon. However, they could fall in the event of a more accommodative SNB policy in an environment of subdued inflation.

Chart: overnight rates, sovereign yields, and new mortgage rates, in %

It should be noted, however, that regardless of the scenario that unfolds, interest rates on new mortgages will remain significantly higher in the short term than the average interest rate applied to the existing mortgage stock (1.3%), which will gradually but slowly increase.

Conclusion

Several factors (nominal appreciation of the Swiss franc, international competition, slow wage growth) are likely to continue to weigh structurally, and probably increasingly, on consumer price trends in Switzerland. These structural disinflationary forces should help preserve savers’ purchasing power and make wage increases more moderate than abroad acceptable.

Inflation is expected to fall back below 2% in 2024, giving the SNB the option of lowering its key interest rate from its peak at the end of 2023. If the SNB does so, sovereign bond yields could follow this downward trend by 2024/2025.

[1] UBS Swiss Outlook – Wages lag behind inflation | UBS Global Themes

[2] Indeed, no bank has any interest in lending at a lower interest rate than the one at which it borrows from its country’s central bank, and no borrower from a bank has any interest in lending at a lower rate.