Summary:

– Education is a major challenge for development.

– At the beginning of 2015, the deadline for the Millennium Development Goals, many countries, mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, are still far from achieving universal access to primary education. Entire sections of the population remain excluded from the education system.

– Even more worrying is that the quality of education in some developing countries is too low to reap the benefits of education.

The post-2015 agenda must therefore clearly specify new, achievable and clear goals to continue increasing access to education and finally recognize the need to improve the quality of education systems.

With the 2015 deadline for the Millennium Development Goals now passed, one thing is clear: there is still a long way to go to achieve the targets set in 2000, particularly in terms of education.

In this article, we review the evolution of access to education in developing countries, while recalling why this issue is crucial. We will then examine the extent to which it is also important for the international community and national governments to recognize the need to invest not only in access to education but also in the quality of teaching.

The message of this article is twofold. Not only is Universal Primary Education (UPE) far from being achieved despite the 2015 deadline, but it is also imperative to improve education systems in developing countries.

Access to education: what are the challenges?

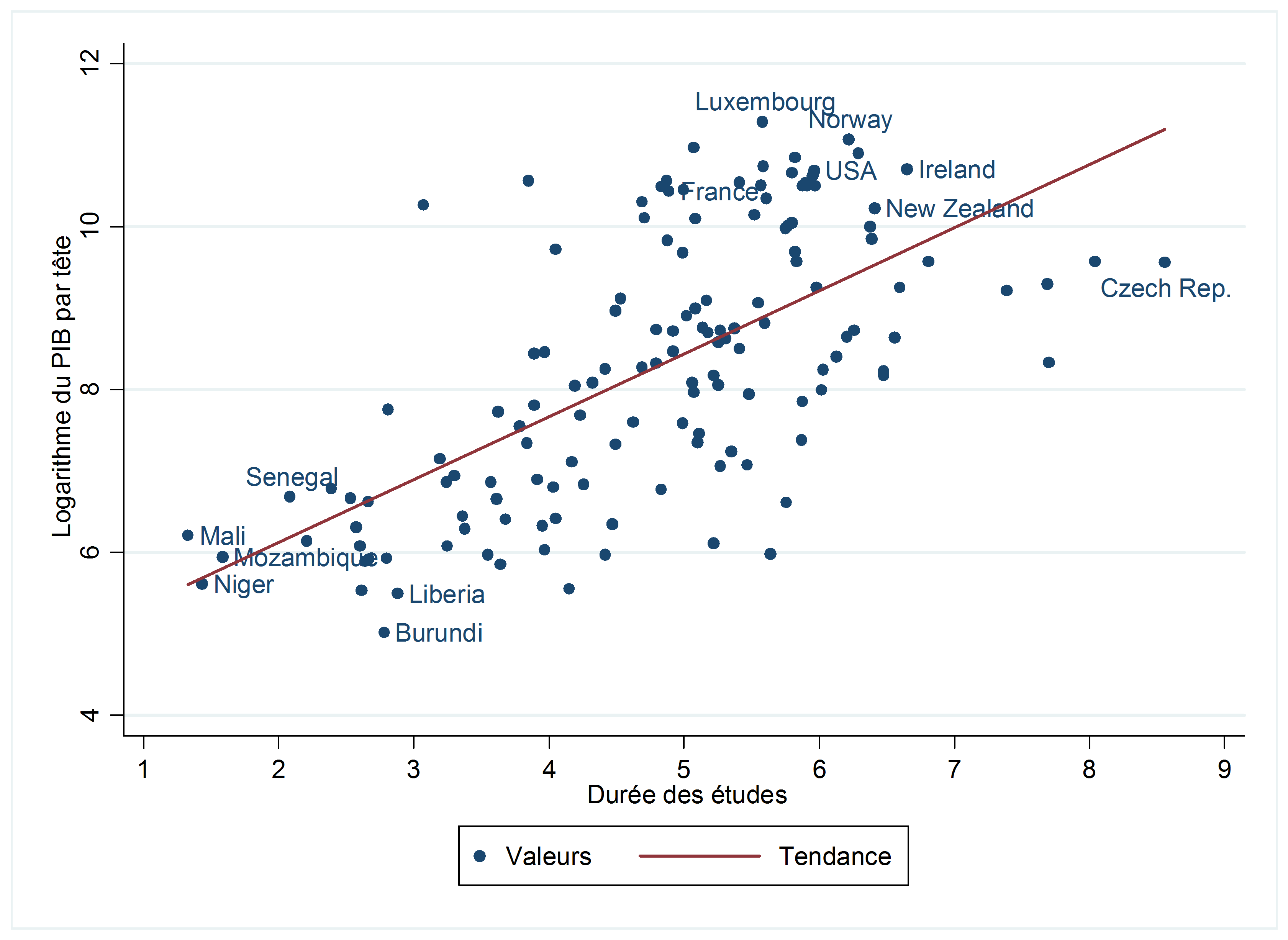

Since the theories of Human Capital (Becker, 1962; Schultz, 1961) and endogenous growth (Lucas, 1988; Romer, 1986), it has been generally accepted that education, at the macroeconomic level, is an essential factor in economic growth and a means of combating all forms of poverty. Indeed, the more educated a population is, the more productive it is, which in turn has a positive impact on economic growth (Figure 1). Education not only has an impact on income levels but also on income distribution. The more educated the population, the more homogeneous the income distribution (UNESCO, 2014). Increasing access to education is therefore a first step toward reducing income inequality within countries.

Chart 1: Correlation between GDP per capita and length of education in 2010

Sources: BSI Economics, World Development Indicators for the logarithm of GDP per capita (in constant 2005 dollars) and Barro and Lee for length of schooling (for all individuals aged 15 and over).

For the most disadvantaged, education is an effective tool for escaping the poverty trap. If all children in low-income countries left school with basic literacy skills, 171 million people could be lifted out of poverty, equivalent to a 12% reduction in global poverty (UNESCO, 2014). Educated individuals, regardless of their background, are less likely to find themselves in chronic poverty (Dercon et al., 2012; Lawson et al., 2006; Ribas et al., 2007).

At the microeconomic level, a positive link has been highlighted between education and income levels. Individuals who have been educated will have a greater ability to adapt to complex tasks and a changing world and will ultimately be more productive and therefore better paid. Economists have shown that each additional year of education is accompanied by an increase in wages. This is known as the rate of return on education. On average, one year of primary education increases wages by 12% (Montenegro and Patrinos, 2014). The rates of return on education are particularly high in developing regions, where educated labor is scarcer. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, an additional year of primary education is associated with a 14% increase in future wages (Montenegro and Patrinos, 2014).

However, the relationship between education and the labor market is less clear in developing countries, as the labor market is segmented between a precarious and dominant informal market and a smaller formal market that offers better career prospects and wages (Ray, 1998; Schultz, 2004). The returns associated with education are higher in the public sector and the formal private sector than in the informal private sector (Kuépié, Nordman, and Roubaud, 2009).

Individuals’ position in the labor market depends in particular on their social background, especially in developing countries, which represents an obstacle to equal opportunities. Parents pass on to their children a certain amount of physical, human, and social capital that determines their future career choices. As access to credit is limited in developing countries, the physical capital passed on by parents is a necessary condition for accessing professional categories that require an initial investment. The human capital passed on by parents to their children may also encourage them to choose the same profession as their parents. In addition, their parents’ social capital (network) facilitates their access to certain professions. Children from privileged backgrounds with wealthy parents working in the formal sector are therefore more likely to access better-paid careers in the formal sector.

Education is a key variable in remedying this phenomenon of unequal opportunities, as it enables children to acquire the human capital necessary to enter the formal market. Educated individuals are more likely to enter the public sector or the formal private sector, both of which offer job security and higher wages, rather than the informal sector (Kuépié, Nordman, and Roubaud, 2009). By providing access to more stable jobs with better working conditions, education helps protect certain categories of workers who are traditionally more prone to exploitation (UNESCO, 2014). It is therefore particularly important to educate girls, as this will enable them to obtain decent jobs and decide how to use their income, which is a first step toward women’s empowerment.

In addition to its direct economic impact on income, promoting education is essential for improving health outcomes. Educated people are better informed about potential diseases and are therefore better able to prevent them. They are also generally better paid, as we have seen, and on average devote more resources to healthcare (UNESCO, 2014). The main channel through which education impacts health is via mothers: the children of more educated women tend to be healthier. This result underscores, once again, the need not to neglect girls’ education (see BSI article » Gender Equality and Economic Development » by Lucia Lizarzaburu). Mothers who have received an education are more likely to seek the help of a competent midwife, have their children vaccinated, etc. (UNESCO, 2014). Gadikou et al. (2013) estimate that half of the lives of children under the age of 5 that were saved between 1990 and 2009 were saved thanks to improvements in women’s education.

Not only does education have an economic impact by improving incomes and promoting economic growth, but it also has an impact on society as a whole by facilitating the emergence of good governance and democracy. Quality education enables individuals to better understand the problems facing society (Evans and Rose, 2007; UNESCO, 2014), to be more supportive of democratic regimes (Evans and Rose, 2012; Shafiq, 2010), and to participate actively in political life (UNESCO, 2014).

Expanding access to education has therefore become a priority for many developing countries. Millennium Development Goal 2, also known as Universal Primary Education (UPE), stipulates that every country must enable all children, boys and girls, everywhere in the world, to complete primary school. Following this international recognition, each country has strived to find ways to increase access to education and spread knowledge among its population. The policies implemented have taken many forms, which can be grouped into two main categories: policies aimed at increasing educational provision (building schools, increasing public spending on education, recruiting new teachers, etc.) and those that seek to stimulate household demand for education (scholarships, conditional cash transfers for children’s schooling, awareness campaigns, etc.).

As we enter 2015, the deadline for the Millennium Development Goals, it is high time to take stock and see whether Education for All is a reality or whether it unfortunately remains a mirage.

Access to primary education: an overview of the situation in developing countries

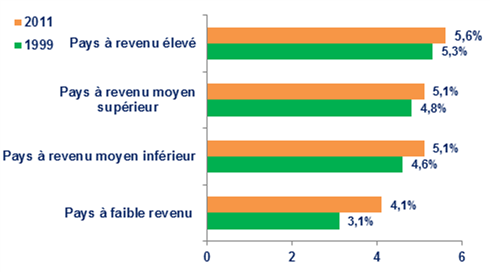

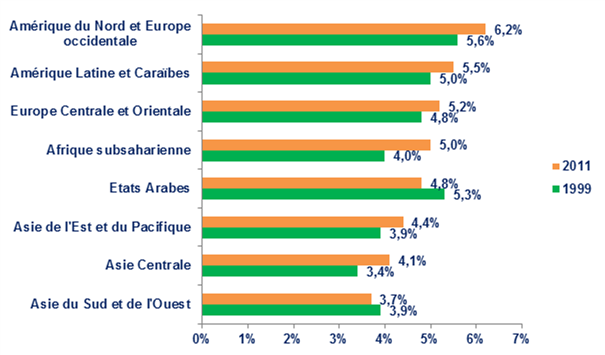

Since the Millennium Development Goals were established, developing countries have increased their commitments to education (Figure 2). In 2011, governments in sub-Saharan Africa spent the equivalent of 5% of GDP on education, a higher share than countries in Asia or the Middle East and North Africa region (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Public spending on education, by income level, 1999 and 2011

Sources: BSI Economics, UNESCO (2014)

Figure 3: Public spending on education, by region, 1999 and 2011

Sources: BSI Economics, UNESCO (2014)

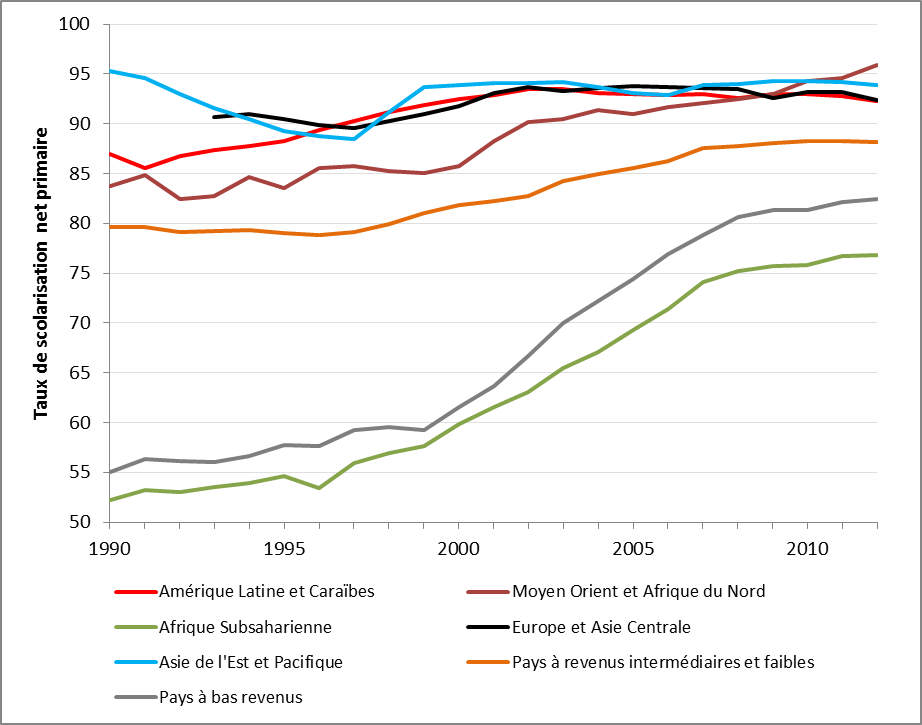

These policies have led to considerable progress, as evidenced by the increase in school enrollment rates (Figure 4). More children now have the opportunity to attend school and the hope of later qualifying for more skilled and better-paid jobs. Between 2000 and 2012, the number of out-of-school children of primary school age fell by almost half, from 102 million in 2000 to 58 million in 2012. In low-income countries, enrollment rates in primary, secondary, and tertiary education rose from 55% to 82%, 20% to 44%, and 3% to 9%, respectively, between 1990 and 2012.[1].

Figure 4: Change in net primary school enrollment rates in developing countries

Sources: BSI Economics, World Development Indicators

This progress has slowed since 2008, and the 2015 target has not been met. One in ten children of primary school age is still not enrolled in school. Thus, despite some significant progress, a large number of children still do not have access to education and remain trapped in poverty. Based on current trends, it will take at least two more generations to achieve the goal of universal primary education (UNESCO, 2014). In sub-Saharan Africa, where more than half of out-of-school children live (Figure 5), the situation is particularly worrying. Based on current trends, the region would not achieve universal primary education until 2052.

Figure 5: Number of out-of-school children of primary school age in 1990, 2000, and 2012 (millions)

Sources: BSI Economics, World Development Indicators

Sub-Saharan Africa, marked by strong population growth, is struggling to accommodate all children in suitable school facilities. Educational provision, i.e., infrastructure and teaching staff, is insufficient to meet growing demand. As a result, 3.3 million new teaching positions would need to be created in order to achieve the Education for All goal by 2030 (UNESCO). In addition, the numerous armed conflicts in the region prevent many children from attending school (United Nations, 2014). Finally, even though demand for education has increased, many parents are still reluctant to send their children to school for a number of reasons. One of the main explanations is the cost of education, which is also a barrier to schooling. Even though many countries have chosen to offer free public education, the opportunity costs associated with education are sometimes so high that the most disadvantaged families cannot afford to send their children to school because it would deprive them of additional income. These costs of education often exceed the benefits perceived by parents, coupled with the often poor quality of education.

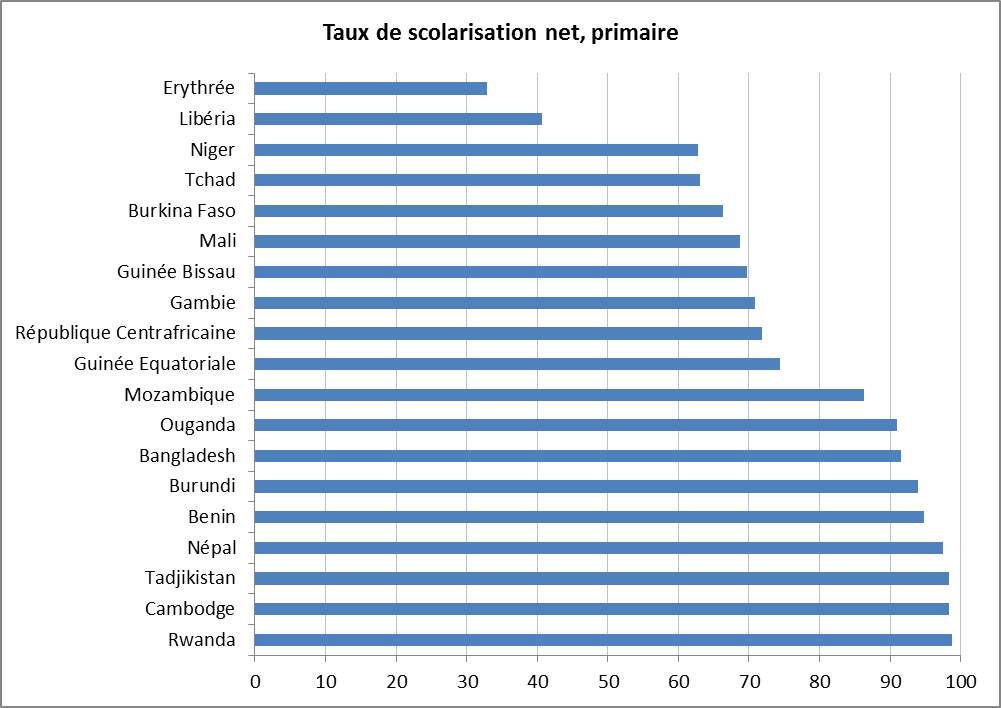

However, this regional analysis masks significant disparities between developing countries (Figure 6). For example, 99% of primary school-age children in Rwanda are enrolled in school, compared with 41% in Liberia and 33% in Eritrea.

Figure 6: Net primary school enrollment rates in selected developing countries (2010-2012)

Sources: BSI Economics, World Development Indicators (latest data available since 2010), for countries listed as low-income countries)

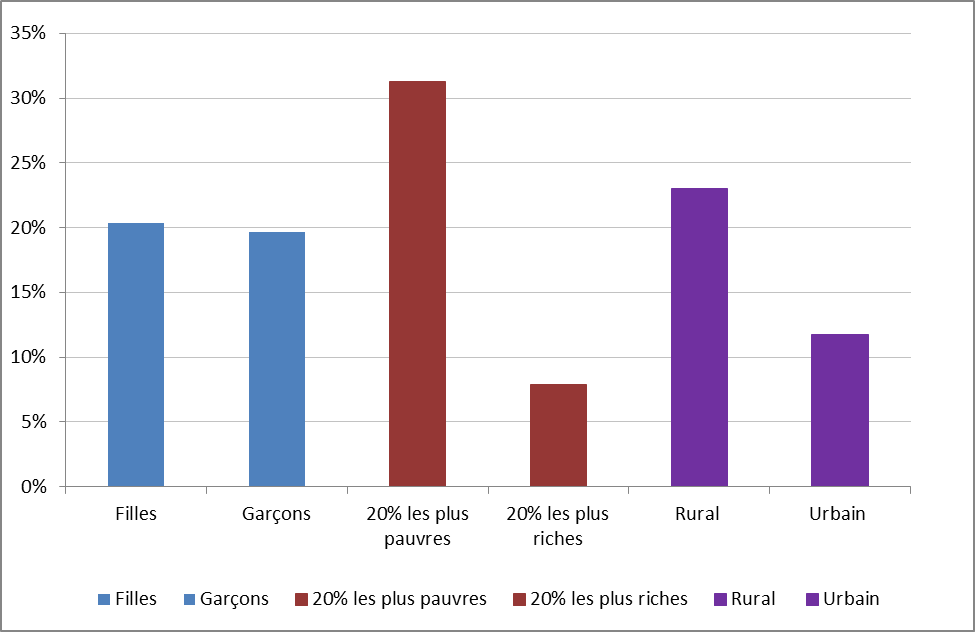

Even within each country, there are glaring inequalities. Even today, despite active policies, children, and particularly girls, from rural and disadvantaged backgrounds remain marginalized (Figure 7). In sub-Saharan Africa, only 23% of poor girls living in rural areas have completed primary school (United Nations, 2014). This situation has significant consequences for the structure of the labor market and inequalities: women and individuals from rural areas or poor backgrounds are unable to compete for the same jobs as urban individuals, which contributes to the reproduction of a segmented labor market.

Figure 7: Proportion of children of primary school age not attending school, 2005-2013

Sources: BSI Economics, Demographics and Health Survey (latest data available since 2005), for 83 countries listed as low- and middle-income countries

Children must complete primary school in order to acquire basic reading and math skills. However, even when they start school, many children drop out prematurely. In developing regions, one in four children enrolled in school does not complete the final year of primary school, a figure that has remained constant since 2000. In sub-Saharan Africa, this phenomenon affects two out of five children.

The quality of education is still insufficient

Giving every child the opportunity to go to school is a necessary but insufficient condition for reaping the benefits of education. Students must also acquire useful knowledge at school that is valuable in the labor market for education to play a role in development. The quality of education was at the heart of the Dakar Education Forum in Senegal in 2000, where the countries present set themselves the sixth goal of improving the quality of education in all its aspects. However, very little progress has been made in this direction, as governments have been more interested in increasing access to education without concern for the quality of the learning process. 250 million children still do not acquire basic reading skills (UNESCO, 2014). The situation is particularly alarming in South and West Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, where only one-third and two-fifths of children, respectively, reach thefourth gradeof primary school and acquire basic reading skills.

Here again, there are significant disparities between children based on their gender, geographic location, and social background. Children from the wealthiest households are not only more likely to attend school but also more likely to acquire basic skills once enrolled. This situation perpetuates inequalities in the labor market. Being a woman is also a disadvantage that amplifies wealth disparities. In Benin, for example, 60% of rich boys stay in school untilthe fourth gradeand acquire basic math skills, compared to only 6% of poor girls (UNESCO, 2014). Such disparities prove that it is crucial to focus education policies on eliminating gender differences. Students from rural areas are also more likely to fail to acquire basic knowledge at school. In some Latin American countries (El Salvador, Guatemala, Panama, and Peru), the gap between rural and urban students’ math and reading skills exceeds 15 percentage points.

It is essential to take the necessary measures to improve learning while expanding access. This is a major challenge, as new entrants to the education system are more likely to come from disadvantaged households. Some countries have succeeded in increasing educational coverage, notably by abolishing school fees, while improving the learning process. In Tanzania, between 2000 and 2007, the proportion of children completing primary school increased by two-thirds, while the proportion of those enrolled in school and acquiring basic math skills rose from 19% to 36%. This is therefore not an impossible challenge or an unattainable dream, but politicians must commit to significant reforms in order to achieve it.

Conclusion

At the start of 2015, it is clear that, despite some notable progress, many children are still excluded from the education system, which represents a major obstacle to development and traps these children in poverty. It is imperative that developing countries do not relax the efforts they have been making since 2000 and focus their policies on children from disadvantaged or rural backgrounds, especially girls. The goal of universal access to education must not overshadow the equally important imperative of making education a weapon against poverty, namely improving the quality of learning in schools. This notion of quality is too often ignored, yet without it, increasing school enrollment would be a futile effort with no impact on the level of development.

The situation remains worrying in some developing countries, and the post-2015 political agenda must prioritize specific objectives for reforming education systems and thus providing everyone with a decent education. This represents a major undertaking, involving not only improving the provision of education (overhauling school curricula, recruiting more teachers and training them better, etc.) but also reducing barriers to demand for education (incentive policies for parents, subsidies for education costs, etc.).

The SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals), which will take over from the MDGs this year, are currently being negotiated, and the issue of education is at the heart of these debates. It has been stated that the quality of education will be an important aspect of these new goals, but it remains to be seen what measures will be recommended and whether they will be truly adequate.

Notes

[1] The primary school enrollment rate is a net enrollment rate, i.e., the percentage of children of primary school age who are actually enrolled in primary school. The secondary and tertiary enrollment rates are gross enrollment rates, i.e., the number of students enrolled at that level of education, regardless of age, expressed as a percentage of the population officially eligible for enrollment at that level.

References

– Becker, Gary S., 1962. « Investment in Human Capital: A theoretical analysis, » Journal of Political Economy, vol. 70(9).

– Gakidou, E., 2013. « Education, literacy and health outcomes, » Background paper for EFA Global Monitoring Report 2013/4

– Kuepie, Mathias & Nordman, Christophe J. & Roubaud, François, 2009.

- David Lawson & Andy Mckay & John Okidi, 2006. "Poverty persistence and transitions in Uganda: A combined qualitative and quantitative analysis," Journal of Development Studies, Taylor & Francis Journals, vol. 42(7), pages 1225-1251.

– United Nations, 2014. « Millennium Development Goals Report 2014. » Report, UNPD.

– Perez Ribas, Rafael & Machado, Ana Flávia, 2007. « Distinguishing Chronic Poverty from Transient Poverty in Brazil: Developing a Model for Pseudo-Panel Data, » Working Papers 36, International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth.

– Debraj, Ray, (1998) Development Economics, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

– Robert, Lucas, 1988. « On the Mechanisms of Economic Growth, » Journal of Monetary Economics 22(1)

– UNESCO, 2014 « EFA Global Monitoring Report: Teaching and Learning: Achieving Quality for All, Report, UNESCO editions.

– Schultz, Theodore W., 1961 “Investment in Human Capital,” The American Economic Review, vol. 51(1)