Summary:

– After a period of confidence prior to the crisis (2003-2007), the current account balance of peripheral countries deteriorated significantly (deficit of 10 points of GDP on average in 2007) due to a sudden stop (flight of foreign capital).

– However, in 2013, despite sufficient external financial compensation, current accounts returned to balance thanks to exceptional mechanisms (TARGET2[1], Troika aid plan[2]).

– While this aid has helped to reduce the current account deficit, it masks a worrying problem: the external sustainability of peripheral countries. Indeed, these countries currently have large external debt positions. The extent of their openness to the outside world highlights a structural weakness: their external dependence.

– In this context, and particularly in the countries of Southern Europe, there appears to be an urgent need to improve and control external positions in order to remedy this dependence. This is a long-term process, the assessment of which raises two questions: if it is possible, how can we predict its rebalancing? What is the financial cost of such a rebalancing for the countries of Southern Europe?

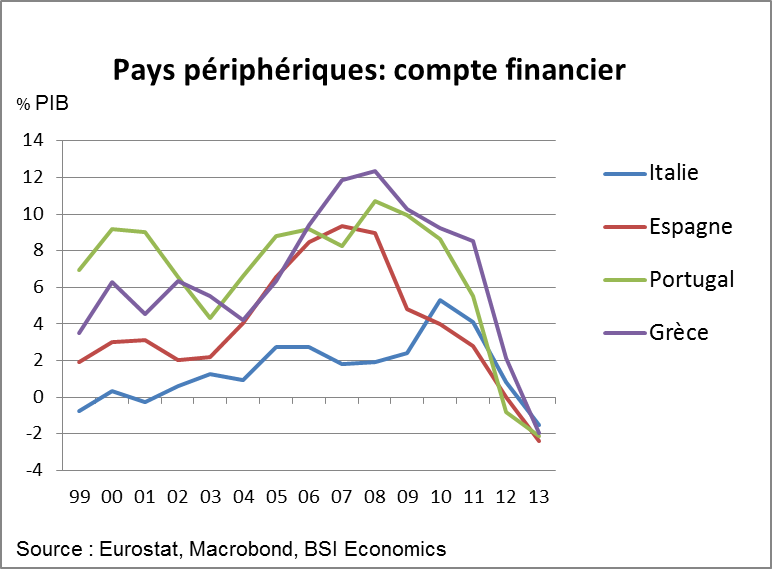

To analyze the origin of excessive external debt accumulation, we need to look at the financial accounts of Southern European countries (a « bottom-up » approach to the balance of payments).

Debt (already high for some countries) began to soar in 2003, reaching its peak in 2008 (led by Greece, closely followed by Portugal and Spain, then Italy further behind). This phase of fragility also marked the beginning of the crisis in the eurozone.

The financial account deficit of these countries will gradually be reduced to reach equilibrium in 2013. Furthermore, our study will examine its accounting counterpart: the current account balance, which is symmetrically balanced. While their financial accounts were balanced, the external debt of the peripheral countries accumulated during this period of confidence (2003-2007), leaving them with a heavily indebted external position (100 to 120 points of GDP for Greece, Spain, and Portugal, and around 20 points of GDP for Italy).

The purpose of our study is to better understand what led to such an accumulation (type of investments, over-indebted sectors, etc.), focusing in particular on the most unbalanced countries: Greece, Spain, and Portugal. To do this, we’ll look at the components of the financial account flows for each unbalanced country since 2003 to get some useful results. We’ll avoid any compensatory effect of assets on the balance by focusing only on inflows: the liabilities side of the financial account.

1 – Blind confidence in external flows, a vulnerability that predisposes countries to crisis

1.1 – Details of incoming financial flows

On the liabilities side of the financial accounts of the most unbalanced countries, we can see several types of flows[3] :

– Foreign direct investment represents the financial commitments of the rest of the world to the country concerned, with the aim of acquiring a long-term interest in its companies;

– Portfolio investments represent short-term financial commitments. They therefore concern securities and the interbank market;

– Other investments include TARGET2 balances and credits and loans (commercial and from the IMF).

In the period of pre-crisis confidence (2003-2008), there were significant inflows from portfolio investments; these short-term and generally volatile capital movements indicate strong commitments by the rest of the world to the assets of Southern European countries (13 points of GDP on average over the period considered).

In Greece, liabilities under Other investments act as a « symmetrical » counterpart to portfolio flows. In a period of confidence, incoming financial flows (in this case, portfolio investments) enable these loans (other investments) to be repaid in part. In Portugal and Spain, the symmetry between « Other investments » and « Portfolio investments » is less obvious. We therefore need to look at the details of these items to understand the fluctuations.

Then, in 2010, there was a sharp reversal of the situation: with the loss of confidence associated with the sovereign debt crisis, first in Greece and then in Portugal and Spain, capital flows fled these countries, leaving large volumes to be repaid, which destabilized the economies. The challenge then became to find financing through other channels (external loans, IMF action). During this painful period, the effects of the Troika and TARGET2 were therefore mainly reflected in the Other investments item.

FDI, on the other hand, involves a much smaller volume of transactions and remains steady over time. This is not surprising: this type of flow mainly corresponds to companies’ investment strategies, which are one-off and medium/long-term in nature. Their volume is relatively low, but the corresponding investment amounts are high.

Portfolio investments therefore account for the majority of the financial commitments of the countries analyzed. A detailed breakdown of these investments provides a better understanding of how they are formed.

1.2 – Details of portfolio investments

It should be noted that portfolio investment liabilities are distributed identically for each of the peripheral countries analyzed: in all cases, the item « shares and UCITS »[4]account for the largest share of outstanding amounts, followed by bonds, closely followed by money market instruments, which account for a smaller share of outstanding amounts.

The debt has therefore mainly accumulated as a result of external investments in equities and UCITS (which are investment funds). This illustrates a certain speculative influence, which has led to a rapid and significant outflow of private foreign capital in the run-up to the crisis: the sudden stop. Nevertheless, a significant portion of these flows is allocated to bonds and money market instruments (interbank market). In this phase of liquidity needs, banks must be resilient in the face of a crisis from which no one knows who will emerge unscathed and whose scope cannot yet be measured. The interbank market is therefore frozen. Lending is following the trend of disengagement from external investment, with confidence at an all-time low.

In Spain, two factors explain the « hesitant » fluctuations between 2007 and 2011. The 2008 real estate crisis triggered a repatriation of external capital, ultimately leading to the sudden stop that marked the beginning of the Spanish sovereign crisis. The contagion spread in 2011, one year after its two partners.

Having studied the distribution of portfolio investments in the financial account, it is useful to complete the study by looking at another component of the financial account, which also represents large volumes: other investments.

1.3 – Details of other investments

Since 2007, there have been significant inflows to monetary authorities. These flows reflect the refinancing of banks in the countries concerned directly with their central banks. With the interbank market frozen (since the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008), the central bank is the lender of last resort.

To finance resident imports not covered by interbank loans, central banks use TARGET 2 (see definition in introduction). The significant deterioration in the « Monetary authorities » item can be explained by these commitments.

The confidence phase in peripheral countries is mainly observed in portfolio investments, which support their imports, financed by this flow of funds. As we can see, this structure is risky because it can lead to sudden stops. To compensate for this shortfall, central banks have taken over, rebalancing their financial accounts while creating new imbalances. Of course, we cannot talk about these refinancing operations without mentioning the intervention of the Troika (aid from the ECB, the European Commission, and the IMF) in bailing out these countries.

This first section introduces the central theme of the study: does such external financial dependence jeopardize sustainability?[5]of the economies concerned?

Using a « top-down » approach to the balance of payments, let us look at the evolution of the current account from the crisis to the present day.

2 – Current accounts that appear to be balanced: a minimum condition for sustainability?

2.1 – Mixed results

Since 2007, the current accounts of the peripheral countries of the eurozone have improved significantly. This would seem to indicate that their economic health is good.

Looking at the graph (below, left), we can see a marked turnaround in 2013, both in terms of its strength and its simultaneity: current account balances are now balanced in peripheral countries (for more information on this subject, see Per Yann Le Floch’s article on the BSI Economics website).

From a financial account perspective, debt has been used to finance and boost exports from peripheral countries: in reality, this debt corresponds to investment capital flows from outside the eurozone into its companies. These flows enable them to produce more and export even more. As we have seen above, this financial dependence on external flows is risky.

In addition, part of the rebalancing that has taken place can be explained by a sharp contraction in domestic demand in peripheral countries: with domestic demand falling, the imports needed to adjust to this new demand are themselves being revised downwards. This has the effect of improving the trade balance (the difference between exports and imports) of countries for an equivalent level of exports. The current readjustment therefore needs to be qualified.

Furthermore, this measure, often used to assess a country’s external sustainability, is in fact only a first step towards achieving it. As current flows provide absolutely no information on the accumulated debt stock, it is necessary to take into account the external position of the countries concerned in order to assess their sustainability.

2.2 – External position: a good measure of sustainability

The analysis is refined in light of the evolution of the external positions of peripheral countries in 2013 (see chart above, right) and highlights a clear structural fragility: peripheral countries are overly dependent on external investment flows. The pre-crisis debt phase of the peripheral countries weighs on the external position, which is heavily in debt.

These imbalances are so significant that they call into question external sustainability.

Conclusion

Looking at the financial accounts of the peripheral countries of the eurozone, the period 2004–2008 was marked by a significant debt phase, due to overconfidence in external capital flows. Although this excess has disappeared, leaving the countries’ financial and current account balances in equilibrium since 2013, this is primarily due to the various mechanisms and interventions put in place in the zone (Troika bailout plans totaling €380 billion in Greece, €78 billion in Portugal, and €41 billion in Spain; TARGET2 balances of peripheral countries in deficit compared with surplus balances for core countries, which reinforces their dominance). Nevertheless, this reduction is only partial and masks extremely high external debt positions. The price of this overconfidence has yet to be paid, as opening up to the outside world has been detrimental to peripheral countries. The question of their sustainability is therefore at the heart of current economic affairs.

Rebalancing the economy is likely to be a long, difficult, and painful process. It will probably require better control of external positions and financial transactions in the broadest sense, as well as the implementation of structural reforms to accelerate the improvement of the external position in the countries concerned, thereby facilitating the efforts to be made.

Notes:

[1]« Trans-European Automated Real-time Grosssettlement Express Transfersystem » isthe paymentand monetary settlement system of the Eurozone. It allows banks to make cross-border transfers via their respective central banks.

[2] Alliance between the IMF, the European Commission, and the ECB for the supervision of the refinancing plans of European Union member states.

[3] In the balance of payments, the financial account is the accounting counterpart to the current account. It shows transactions that increase residents’ claims on or liabilities to non-residents. Source: « La balance des paiements » (The Balance of Payments) by Raffinot and Venet.

[4] Undertakings for collective investment in transferable securities.

[5] Assessing a country’s sustainability involves analyzing the evolution of its debt stock in relation to its overall wealth. It is a dynamic, long-term view.

References:

– « Rebalancing: Current account adjustment and real exchange rate depreciation, » European Weekly Analyst 11/44

– « Achieving fiscal and external balance: The price adjustment required for external sustainability, » European Weekly Analyst 12/01

-“Achieving fiscal and external balance: The price of competitiveness,” European Weekly Analyst 12/02

-“Rebalancing: Current accounts and how to stabilize net debt”, European Weekly Analyst 11/39

-Hobza A. and Zeugner S., July 2014, « The imbalanced balance and its unravelling: current accounts and bilateral financial flows in the euro area, » European Commission, Economic Papers 520

-Di Mauro F., Pappadà F., « Euro area external imbalances and the burden of adjustment, » May 2014, ECB, Working Paper Series No. 1681

-Meunier N. and Sollogoub T., 2005, “Economie du risque pays” (Country Risk Economics), Collection Repères, published by La Découverte

-Marc Raffinot, 2003, “La Balance des Paiements” (The Balance of Payments), Collection Repères