Abstract

– Credit ratings bridge information asymmetries in the bond market and, in theory, determine the interest rate between investors and borrowers.

– Sovereign ratings can have a significant impact on interest rate fluctuations, which can put pressure on a country’s solvency.

– The opaque methodology used by agencies seems to give them significant subjective discretion in assessing sovereign risk.

– However, it now appears that markets are no longer waiting for announcements from agencies to assess risk and apply unsustainable rates to poor performers.

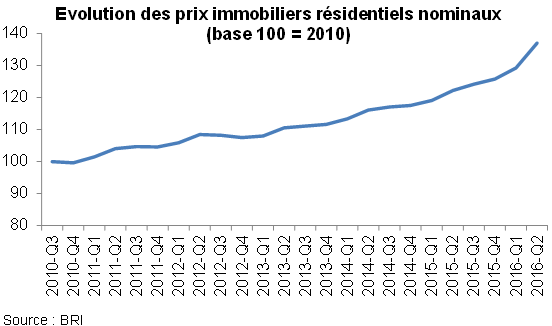

Rating agencies were heavily criticized during the 2008 financial crisis for their poor assessment of the risk associated with real estate securities, known as « subprime structured products. » The vast majority of these securities were given the highest AAA rating, yet the value of these assets collapsed as real estate prices fell. At the height of the debt crisis in Europe, rating agencies were accused of accelerating Greece’s bankruptcy and amplifying the difficulties of certain peripheral countries (notably Portugal and Ireland, and to a lesser extent Italy and Spain) in accessing financial markets. Their methodology and role in the markets are now being seriously questioned.

Rating agencies: who are we talking about?

The rating industry is made up of three major players (Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch Ratings), with the first two accounting for 40% of the market and the third for 10%. Their mission is to bridge the information gap between investors and borrowers (particularly companies and governments) in the financial markets. They therefore fulfill a dual purpose, satisfying both creditors and debtors, since both parties benefit from information that facilitates the transaction. The agencies monetize their expertise on the one hand with economic and financial agents wishing to outsource counterparty risk analysis and on the other hand with securities issuers seeking to use the bond markets to finance themselves. In the case of sovereign ratings, this involves providing investors with comprehensive and accurate information on a country’s ability and willingness to repay its creditors. This need for information has become even more acute with the globalization of markets and the internationalization of public debt holders. Since investors can purchase debt issued by foreign countries, ratings are a necessary source of comparison in their choice of geographical allocation.

Agency ratings are therefore crucial in determining the interest rate that issuers will have to pay on the capital markets. There is an inverse correlation between the rating and the interest rate paid by the issuer. The highest rating (AAA) indicates a secure and liquid security with zero probability of default. A highly rated issuer will therefore enjoy privileged access to financial markets and benefit from low borrowing costs. Conversely, the lower the issuer’s rating, the more difficult its access to markets and the higher the interest rates at which it must finance itself, as investors demand a high risk premium. These securities are in fact less liquid, meaning they cannot be easily traded between investors, as the risk of default is ever-present. The table below provides an overview of the agencies’ rating scale. It distinguishes between « Investment » (low risk of default) and « Speculative » (significant risk of default) categories. Within this rating scale, there are sub-categories (+ and -), bringing the total number of ratings to 21. In addition, the agencies accompany their ratings with information on theoutlook for rating changes in the short and medium term. This information reflects expectations regarding the evolution of issuers’ creditworthiness. A negative outlook implies a risk of further downgrading of the issuer if its economic and financial situation does not improve (and vice versa for a positive outlook). At the beginning of 2013, in the Eurozone, only Finland was rated AAA with a stable outlook by all three agencies.

Economic performance reflects a country’s ability to generate growth (variables used: growth, inflation, etc.). The analysis of public finances makes it possible to assess the trajectory and long-term sustainability of public debt (public debt, public deficit, debt service, etc.). External risk analysis seeks to measure countries’ integration and dependence on external factors in the exchange of goods and capital (balance of payments, debt held by non-residents, etc.). Political outlooks assess monetary flexibility and the quality of institutions within the economy.

Each agency uses (more or less) the same explanatory variables, with only the weighting of the factors changing. It should be noted that detailed information on the quantitative models used by the agencies remains opaque, as only Fitch Ratings publicly discloses the weighting of its model.

These models form the basis of the work carried out by teams of analysts to issue the final rating for a sovereign issuer. However, in 2010 at Fitch Ratings[1], only 28% of the ratings produced by the model corresponded to the countries’ current ratings, leaving a significant degree of discretion in the rating process. This subjective assessment, particularly in the analysis of the political environment, therefore plays a crucial role in rating decisions. Indeed, a country such as the United Kingdom benefits from a AAA rating (albeit with a negative outlook) from all agencies thanks to an ultra-accommodative monetary policy, while at the same time public debt has reached nearly 100% of GDP, the budget deficit has been widening since 2007, and the country has been in recession for four of the last five quarters! This methodology therefore raises questions about the predictive capacity of the models used by the agencies.

According to a report[2]by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) dated October 2010: « Since 1975, all sovereign issuers that have defaulted were in the speculative category one year earlier. However, the ability of agencies to predict a default in the medium term is questionable, given that Greece, Ireland, and Portugal were rated A+, AAA, and AA– respectively until 2009. Greece has since defaulted on its debt, and Ireland and Portugal have called on the IMF for help in meeting their financing needs.

Do the agencies’ decisions influence the behavior of agents?

A study conducted by the IMF[3]between 2007 and 2010 on Eurozone countries shows that a country’s rating downgrade has a significant impact on interest rates and CDS levels[4]not only of the downgraded issuer but also of other members of the zone. Since its creation, the degree of trade and financial integration achieved in the eurozone has increased the dependence of members on each other, and as a result, the consequences of the agencies’ decisions extend beyond borders. The best example is the case of Greece: since the holders of Greek public debt are spread across the entire eurozone, the downgrading of the Greek government to speculative grade and its subsequent default sent shockwaves through CDS levels, interest rates, and stock market indices across all European countries.

More generally, the agencies’ decisions can prove crucial when a sovereign issuer is about to be downgraded to speculative grade. This is because institutional investors (insurers, banks, pension funds, etc.), which remain the main buyers of sovereign debt, are constrained by regulations (Basel III for banks and Solvency II for insurers) that require them to hold only investment grade securities (above BB+). The Spanish case could therefore be problematic in 2013, as its rating is close to this threshold (BBB– from S&P and Moody’s, BBB from Fitch). Institutions would then be obliged to sell their holdings, causing a mechanical rise in Spanish interest rates and making it difficult for the government to finance its debt. The sustainability of public finances could therefore easily be called into question by this self-fulfilling process.

However, it seems that the impact of the agencies’ decisions is not obvious, as financial markets apply interest rate levels based on their own perceptions of government risk. According to Fabrice Montagné, an economist at Barclays, « The market is generally ahead of the rating agencies and adjusts prices well before the ratings are published. » While agencies assess the intrinsic sovereign risk of each issuer—i.e., its ability to repay—financial markets take a more global view, as they arbitrate their allocation by comparing the risk across all sovereign issuers. Certain countries, considered safe by investors (known as » core » countries), therefore enjoy their status as safe havens even when their economic fundamentals are poor. In 2011 and 2012, investors rallied ( strong increase in demand for these securities) around debt issued by core countries in order to secure their financial asset portfolios as tensions on peripheral countries became increasingly pressing. Thus, today, despite France’s loss of its AAA rating (from S&P and Moody’s), the government is borrowing at historically low rates, even though growth and activity are sluggish and deficit reduction targets will not be met.

Conclusion

Financial disintermediation (increased use of the bond market for financing) has made the role of rating agencies indispensable. The information provided by agencies is necessary for setting interest rates on the sovereign bond market. But it is not the only explanatory variable. Today, the dichotomy between safe and risky countries within the investment universe is a more decisive factor than the rating itself.

In addition, agency ratings must be accompanied by an internal second opinion from economic teams. By comparing different points of view, sovereign debt buyers will have comprehensive information to inform their investment decisions.

References

“Sovereign Rating Methodology,” Fitch Ratings, 2011

“Sovereigns: Methodology and Assumptions,” Standard & Poor’s, 2011

“Sovereign Bond Ratings,” Moody’s Investors Service, 2008

“Sovereign Credit Ratings: Shooting the Messenger?”, House of Lords, 2011

Notes

[1]New Sovereign Rating Model, Fitch Ratings, October 2011

[2]The uses and abuses of sovereign credit ratings, IMF Financial Stability Report, October 2010

[3]Sovereign Rating News and Financial Markets Spillovers: Evidence from the European Debt Crisis, IMF Working Paper, 2011

[4]CDS: a credit default swap is a financial protection contract in the event of counterparty default.