Why EURIBOR has lost its meaning since the crisis

The EURIBOR (Euro Interbank Offered Rate) is a benchmark rate used for many financial products and employed by the vast majority of banking professionals and academics. It is often interpreted as the rate at which banks could borrow on the markets (without collateral). This article (based on a recent academic paper) explains that this interpretation was fairly accurate before the crisis, but is no longer the case. After the 2008 crisis, the EURIBOR became disconnected from the rates at which the vast majority of banks in the Eurozone could actually borrow unsecured: this rate became representative only for a tiny handful of banks, and therefore lost much of its meaning as a benchmark rate.

What exactly is EURIBOR?

The EURIBOR is a rate calculated on the basis of a survey in which a panel of representative banks (only 20 today, listed here) declare the rate at which they would be willing to lend to a « prime » bank . The EURIBOR is the average of the rates announced in this survey. The fact that « prime » banks are involved means thatthe EURIBOR is sometimes referred to as the « best rate for the best banks. »

The EURIBOR was a good indicator of banks’ financing conditions before the crisis, but this has not been the case since 2008.

Before the crisis, financing conditions were very uniform: the market viewed banks as low-risk, and as a result, the rates at which virtually all banks could borrow without collateral were very close to the EURIBOR.

The 2008 crisis completely changed the situation. Banks are now perceived as much riskier. Figure 1 (from Pinter and Boissel (2016)) shows the average credit default swaps (CDS) of the 10 banks perceived as the riskiest and the average CDS of the 10 banks perceived as the least risky among a sample of 40 major European banks. While before the crisis there was virtually no difference between the risk of the top 10 and the risk of the bottom 10 (as perceived by the market), since 2008 the difference has exploded. Worse still, even the average CDS of the 10 banks perceived as the « least risky » has moved significantly away from 0. In other words, the banks perceived as « risk-free » on which the EURIBOR survey implicitly relies are now only a tiny minority of banks (see also the excellent article by Taboga (2014) on this point).

Figure 1: CDS of the 10 riskiest banks versus CDS of the 10 least risky banks

Source: Pinter and Boissel (2016, Economics Letters)

An alternative indicator to EURIBOR

Based on this observation, a new study (Pinter and Boissel, 2016, Economics Letters) has developed an alternative indicator to EURIBOR. The indicator, developed for 40 banks in six major eurozone countries, is based on the following simple relationship:

Interest rate for risk-free borrowing = risk-free rate + risk premium + liquidity premium

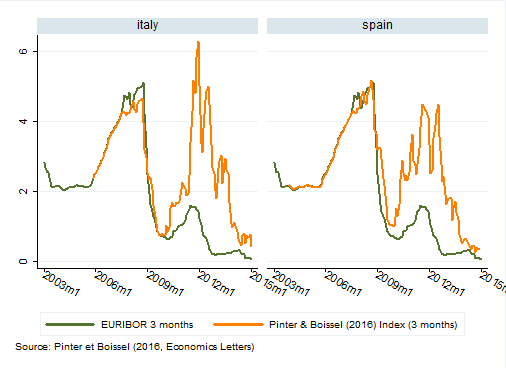

By taking these components into account for each bank, the indicator provides a much more accurate real-time picture than EURIBOR of the rate at which a bank could borrow. By aggregating this data at the national level, we can see how significantly the EURIBOR has underestimated the rates at which banks could theoretically borrow over the past eight years, particularly for peripheral countries (Figure 2).

Figure 2: EURIBOR versus actual unsecured financing costs (Pinter & Boissel Index (2016)) for Italy and Spain:

Conclusion

In the post-crisis world, EURIBOR has become the rate at which only a handful of banks can borrow without collateral. In other words, EURIBOR has become an indicator that is disconnected from the financing conditions of the vast majority of banks in the eurozone. At a time when certain banks in Germany and Italy that are normally considered safe are also now perceived as risky, it is highly likely that EURIBOR will not regain its pre-crisis relevance for several years to come…

Julien Pinter

Sources and additional information:

Julien Pinter, Charles Boissel, The Eurozone deposit rates’ puzzle: Choosing the right benchmark, Economics Letters, Volume 148, November 2016, Pages 33-36. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165176516303536)

(long version in CES Sorbonne Working paper here)

Taboga, M. (2014): What is a prime bank? A Euribor-OIS spread perspective. International Finance, 2014, vol. 17, pp. 51-75.