Summary

· Following the deregulation of credit across the Nordic countries in the 1980s, a real estate bubble formed, leading to a major banking crisis.

· Faced with rising insolvency among private agents and non-performing loan rates, the Nordic authorities had to implement a rescue plan to safeguard their banking systems.

· For exogenous (strong global growth) and endogenous (structural reforms) reasons, the Nordic economies experienced a substantial rebound after the banking crisis.

· While the drivers of this crisis are very similar to those of 2008, the global economic environment is now very different from what it was then, which limits comparisons in terms of banking crisis management.

NB: Denmark is not discussed in this article, as the country did not experience a systemic banking crisis like its neighbors. Despite a sharp increase in losses for Danish financial institutions, very few called on the public sector for support (bailouts). The main reason for Denmark’s outperformance lies in the ex ante implementation of reforms, both in the tax system (reduction of interest expense deductibility for individuals, which limited the growth of the real estate bubble) and in financial supervision (much more stringent monitoring and implementation of solvency ratios). Thus, unlike its peers, the conditions introduced by the Danish authorities enabled the country to avoid a major banking and currency crisis.

The Nordic banking crisis of the early 1990s resembles in every respect a classic financial crisis as defined by Reinhard and Rogoff (This time is different, 2008 ): the bursting of the financial and real estate bubbles, fueled by rampant credit growth, led to a deterioration in the quality of bank assets. The public authorities intervened directly in the financial sector to bail it out and put in place the tools needed to clean up the system. At the same time, the reforms carried out by governments enabled a return to high growth.

I. Credit overheating and the real estate bubble led to the most serious crisis in the Nordic countries.

The Nordic authorities decided to remove credit controls and rationing (ending loan caps and foreign exchange risk limits) in Norway in 1984, Sweden in 1985, and Finland in 1986. With real interest rates paid by borrowers in negative territory due to high inflation and, above all, the possibility of deducting almost all interest expenses from income tax, households took advantage of these regulatory changes to take on heavy debt. The international liberalization of capital markets in all Nordic countries was also a factor that significantly stimulated credit growth. With nominal interest rates higher than in Europe, the influx of foreign capital and the establishment of numerous foreign bank subsidiaries significantly increased the available liquidity and thus fueled the rise in credit, particularly in foreign currency, while increasing these countries’ dependence on external creditors.

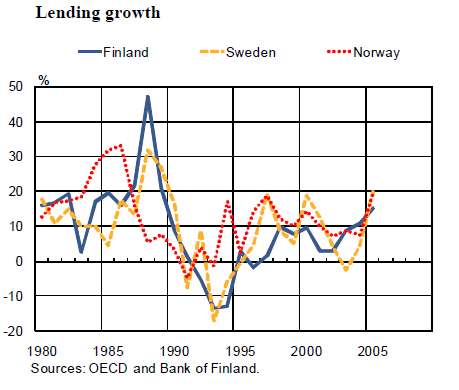

In fact, credit growth was phenomenal in all the Nordic countries, reaching +47% and +32% year-on-year in Finland and Sweden respectively in 1988 (see Figure 1). In Sweden, outstanding loans to the non-financial private sector rose from 85% of GDP in 1985 to 130% in 1990.

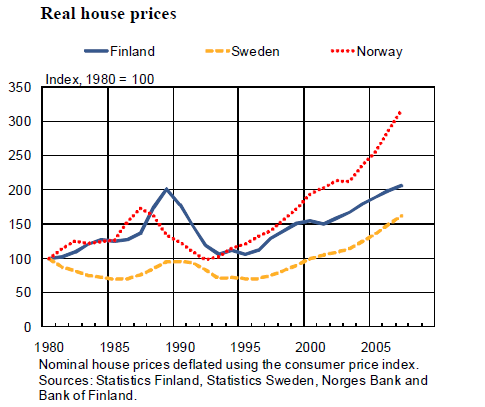

This credit boom generated multiple bubbles in both the financial sector (with Swedish and Finnish stock market indices rising by nearly 300% between 1985 and 1989) and the real estate sector (see Chart 2). However, faced with this credit boom, banks and local financial authorities failed to put in place the necessary monitoring mechanisms to assess the risk to banks’ assets.

Figure 1: Credit growth

Figure 2: Real estate price trends

The international context also played a major role in the emergence of this crisis. First, with the reunification of Germany, key interest rates rose across all European countries, leading to higher borrowing costs and an increase in insolvencies, as Nordic loans are mainly variable-rate loans. Secondly, the collapse of the USSR had a particularly severe impact on Nordic exports, especially those from Finland, as the USSR was its main trading partner, which had a significant impact on growth. Finally, multiple speculative attacks on Nordic currencies forced local central banks to devalue their currencies.

All of these risk factors, both domestic (real estate bubble) and international (significant external debt, speculative attacks on local currencies, and declining exports), led to a sharp deterioration in bank assets. Between 1990 and 1993, provisions for losses on bank loans reached historically high levels: 2.7% in Norway (as a percentage of total loans), 2.9% in Denmark, 3.4% in Finland, and 4.8% in Sweden.

II. The measures implemented by the authorities ultimately made it possible to stem the effects of the crisis and consolidate the foundations for a phenomenal economic rebound.

Faced with a shortage of liquidity in local and foreign currency, the Nordic central banks first worked to refinance the banks. The authorities also set up a guarantee fund for all bank liabilities (unlimited guarantee excluding equity/capital). On the fringes of these interventions, and before the public authorities took action, « private » solutions were implemented to overcome the crisis. In some institutions, shareholders were directly involved, either partially (as was the case with Skopbank in Finland) or totally (the shares of Gota Bank in Sweden held by the private sector were automatically written down to zero). However, given the scale of the recession and the banking restructuring that needed to be implemented, the public authorities had to put additional tools in place.

Bank resolution agencies, independent of the government and the central bank, were created to manage the injection of public funds into the banking system, and bad banks were set up (except in Norway, where some banks took the initiative to create bad banks themselves). These structures made it possible to centralize the banks’ risky assets (real estate) and dilute them over time (over a 15-year period, with the gradual sale of assets). These companies, backed by state guarantees, helped to ensure that the recognition of losses on bad debts did not affect the solvency of the banks.

Banks involved in recapitalization had to implement major restructuring, particularly through mergers, in order to improve their profitability and solvency. Finnish banks recorded losses until 1996. One of the consequences of this restructuring was the internationalization of banks, with nearly two-thirds of Finnish banks now in foreign hands.

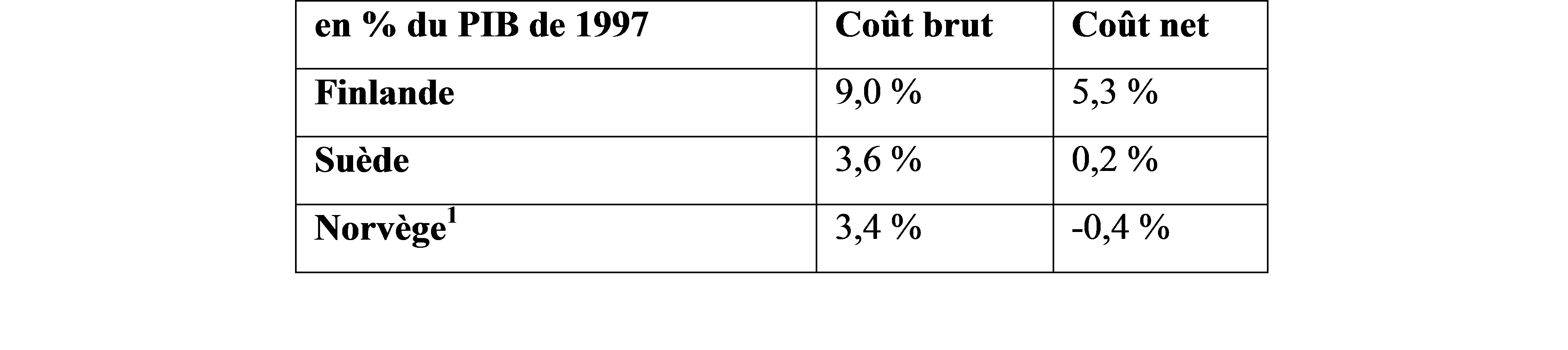

The total costs of the bailout are listed in the table below, which distinguishes between the gross cost (including the recapitalization of certain banks and the capital injection into bad banks) and the net cost, which takes into account the revenue received by the bad banks following the sale of certain assets and the sale by the state of the shares in banks acquired at the height of the crisis. The residual cost of the crisis was particularly high in Finland (5.3% of 1997 GDP) due to the severity of the recession and the high volume of non-performing loans initially held by the banking sector. In contrast, the crisis was much less costly for the Swedish and Norwegian governments. Norwegian taxpayers even benefited at the end of the crisis once the government’s holdings had been sold, thanks to the significant increase in the value of the shares held.

Fiscal cost of the government’s financial sector rescue plan

Source: S. Honkapohja, Bank of Finland, 2009 1as a percentage of 2001 GDP

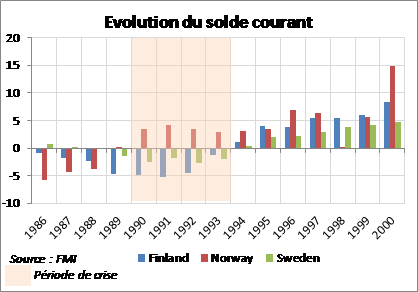

One of the main lessons to be learned from this crisis is the importance of identifying warning signs: credit booms and the emergence of large current account deficits appear to be the main indicators of crisis.

III. What was the crisis exit strategy at the time?

Beyond financial responses to limit the spread of the banking crisis, Nordic governments, particularly Sweden and Finland, implemented numerous structural reforms that bore fruit in terms of growth as the crisis ended.

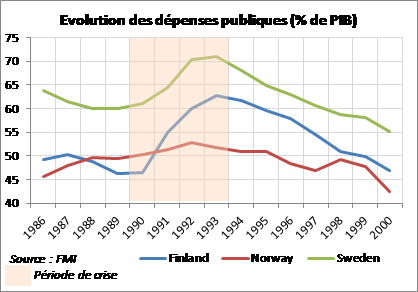

Significant fiscal consolidation was carried out in Finland and Sweden from 1993 onwards. In total, between 1994 and 1998, the consolidation effort is estimated at 8 percentage points of GDP. As can be seen in Figure 4, fiscal adjustment in both countries was achieved through drastic reductions in public spending, particularly on social and operating expenses. At the same time, public finance governance was strengthened in order to control public spending in line with the economic cycle. In addition, the Nordic countries liberalized entire sectors of their economies to unleash growth potential and reduce the role of the state in areas such as health, education, and pensions. Finally, the growth model was strongly redirected towards exports, in a context of booming international trade. As a result, exports rose from 33% of Swedish GDP in 1993 to nearly 50% in 2000. By 1993, the eurozone’s current account was in surplus (Figure 5).

All of these reforms were the result of extensive consultation between the government and the social partners. The population’s awareness of the need for reform was one of the pillars that helped pull the countries out of the crisis.

Figure 4: Change in public spending

Figure 5: Change in the current account balance

IV. Is the parallel between the Nordic crisis of 1993 and the global crisis of 2008 obvious?

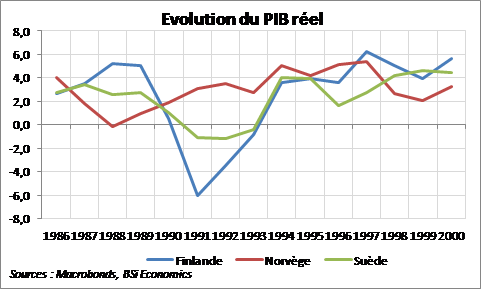

The impact of the banking crisis that ravaged all the Nordic countries was so severe that Reinhard and Rogoff (This Time is Different, 2008) ranked it among the five major crises in history. As can be seen in the graphs below, the total decline in GDP between 1990 and 1993 was significant, particularly in Finland, the country hardest hit by the crisis, where GDP fell by 10% over this period (-5% in Sweden). The unemployment rate reached historically high levels (16% in Finland and 9.4% in Sweden). However, although the Swedish economy followed the same trajectory as its Finnish neighbor, the magnitude of the decline was significantly less severe. Thus, the scale of the economic recession and the decline in both financial and real estate asset prices are comparable between the banking crisis of the 1990s and the financial crisis of 2008.

Figure 6: GDP growth in the Nordic countries

There are many similarities between the two crises in terms of the measures taken to restructure the banking sector: i) a bailout was carried out through capital injections, with the riskiest institutions being nationalized (Northern Rock, Dexia), ii) asset-relief vehicles were set up to liquidate the risky assets (mainly real estate, as in Ireland (Nama) and Spain (Sareb)) of banks undergoing restructuring, iii) many banks merged in order to strengthen their solvency and profitability (as was the case in Spain in 2010), iv) in certain specific cases, a bail-in of private shareholders was implemented (Banco Espirito Santo in 2014). These aspects are largely part of the recommendations of the Liikanen report, which itself inspired the establishment of the Single Resolution Mechanism, with creditors being called upon to contribute ( » bail-in « ) before any » bail-out » takes place.

However, while these two crises stemmed from similar circumstances, namely the creation of a real estate bubble (see the book « House of Debt »by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi) following the deregulation of the banking system, the surrounding economic context is now completely different. Admittedly, the weight of the structural reforms undertaken by the government partly explains the economic rebound seen after 1993, but it was not the only explanatory factor. Growth in international demand significantly supported activity in the Nordic countries, while the depreciation of their currencies helped restore the price competitiveness of Scandinavian products. This was an important factor that enabled the Nordic countries to emerge from the crisis and return to a path of sustained positive growth much more quickly than is the case today. In fact, by 1994, just four years after the start of the recession in Finland and Sweden, GDP was growing again. In the current crisis, unfortunately, there has been no sign of a sustainable rebound in activity, even though the financial crisis began six years ago. The determination shown by all European countries to reduce public and private debt since 2010 has contributed significantly to economic stagnation.

It is therefore not easy to establish a link between the implementation of structural reforms and the rebound in growth, as certain exogenous factors also impact an economy’s ability to emerge from the crisis.

Conclusion

Today, the Nordic countries continue to benefit from the reforms implemented in the wake of the banking crisis of the early 1990s (to a lesser extent in Finland[1]). Fiscal discipline, even in years of strong growth, a strengthened banking sector supervisory framework, and the role of exports as the main driver of growth have enabled Sweden and Norway to outperform other European countries in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. These countries, which relied on exports in their crisis exit strategy, have also benefited from strong domestic demand. Investment was driven by growth in export order books and robust domestic consumption: on average between 1994 and 2000, investment grew annually by 9.8% in Finland and 7.7% in Sweden, compared with 4.9% in Europe. While the Nordic countries benefited from an increase in domestic and external demand, today’s European countries do not have the same growth drivers. Indeed, those countries that have opted for internal devaluation in order to benefit from renewed cost competitiveness are doing so at the expense of household purchasing power and therefore domestic demand.

Furthermore, the political and social consensus on the need for reform that emerged in the 1990s was a driving force behind the Scandinavian rebound both in the 1990s and today. It is this need for reform that the countries of the eurozone, led by France and Italy, are seeking to draw inspiration from in order to return to a path of sustainable growth and reduce the burden of public debt.

Bibliography:

The 1990s financial crises in Nordic countries, Seppo Honkapohja, Bank of Finland, 2009

The Nordic banking crises in the early 1990s – Resolution methods and fiscal costs, K . Sandal, Norges Bank, 2004

What lessons can be learned today from the crisis of the 1990s in Sweden?, Trésor-Eco, 2012

More evidence supporting the house of debt, A . Mian & A. Sufi, 2014

Notes:

[1]See the BSi Economics article: http://www.bsi-economics.org/index.php/macroeconomie/item/207-finlande-crise-structurelle-conjoncturelle