Abstract :

– Current account imbalances in the euro area widened significantly during the decade from 1999 to 2008, contributing to the sovereign debt crisis

– A rebalancing is now underway, through a marked improvement in the current accounts of peripheral countries

– However, this rebalancing is based on « internal devaluation » measures, which are not sustainable in the medium term

Introduction

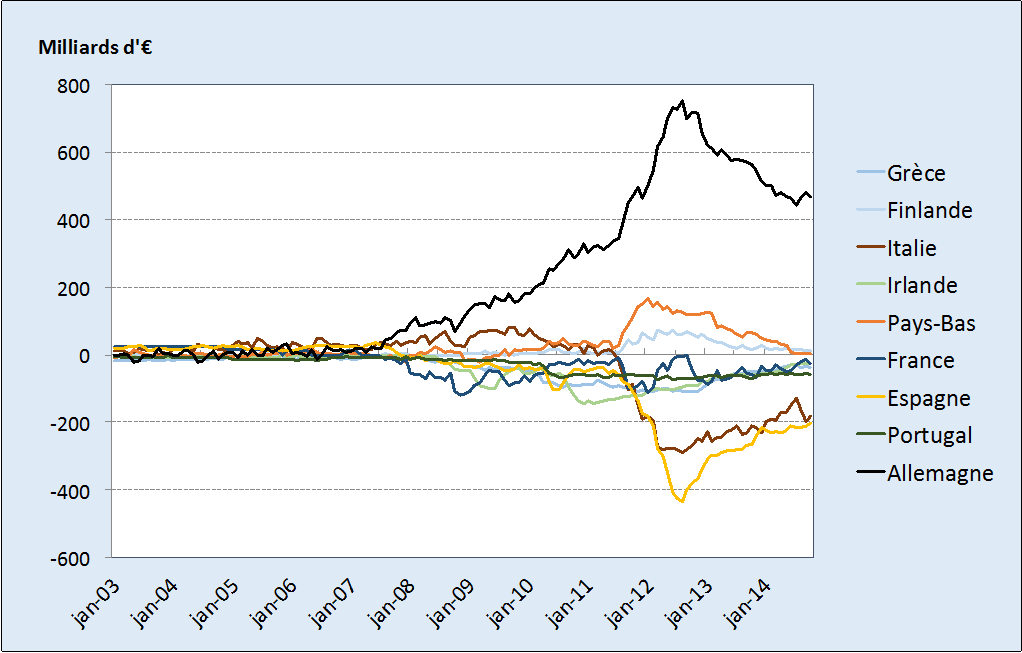

An analysis of TARGET 2 balances (the payment platform between national central banks within the Eurosystem) illustrates the imbalances between euro area central banks since 2008 and their relative contraction since the end of 2012. In countries that have lost investor confidence, TARGET 2 balances have deteriorated since 2008, while the opposite has been true in countries that have benefited from capital repatriation, such as Germany and the Netherlands. Their investments in other euro area countries are declining, while they continue to run substantial current account surpluses. If the peripheral countries did not have the euro, these imbalances would have resulted in devaluations (a decrease in foreign exchange reserves).

Figure 1. TARGET 2 balances, 2003-2014

Source: Author, Macrobond, BSI Economics

I – The role of current account imbalances in the eurozone crisis

A- The rise of three macroeconomic imbalances up to 2008

The cumulative current account balance of Spain, Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Ireland reached -8% of their GDP in 2008. At the same time, the net external debt of these countries reached 60% of their GDP.

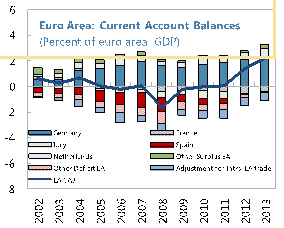

In contrast, Germany and the Netherlands ran surpluses during this period. Figure 2 shows that the broadly balanced current account balance of the euro area actually masks significant disparities between the center and the periphery.

Figure 2. Composition by country of the euro area current account, 2002-2013

Source: IMF, Macrobond, BSI Economics

The deterioration in the current accounts of the peripheral eurozone countries is due to 1) strong growth in domestic demand, which is supporting imports, and 2) a decline in these countries’ competitiveness, which is undermining their export performance.

First, growth in domestic demand is supporting an increase in imports. Membership of the eurozone has enabled peripheral countries to benefit from low interest rates and therefore very favorable borrowing conditions, as well as an influx of foreign capital attracted by the prospect of these countries catching up economically. The homogeneity of spreads and low interest rates during the 2000s led to a sharp increase in private and public debt. In addition, rising wages and relatively low unemployment rates led to strong growth in domestic demand and imports.

Secondly, declining competitiveness is reducing export performance. The abundance of liquidity in peripheral countries has benefited non-tradable sectors such as construction and retail. In addition, strong wage and price growth has eroded the price competitiveness of tradable sectors, leading to a decline in exports. The combination of these two phenomena has led to strong growth in debt, largely external, and a deterioration in competitiveness in a context of limited policy room for maneuver (fiscal policy constrained by public deficits and no monetary policy autonomy).

At the same time, the center is improving its position. The dynamics of the countries in the center and north of the eurozone are radically opposed. The case of Germany is particularly representative, with the country achieving very large current account surpluses. With nearly 6% per year over the last decade, it is also the country with the largest surpluses in absolute terms, €283 billion in 2012. There are several reasons for this. Until 2011, Germany had the least dynamic domestic demand (from 2000 to 2011, it grew by just over 5%), resulting in a limited increase in imports, while its exports benefited from strong demand from other countries in the zone and low price elasticity for its products (high added value and high non-cost competitiveness). At the same time, labor costs and the price index rose more slowly in Germany than in other countries in the eurozone, giving it a competitive advantage. Over the period 2002-2012, the Netherlands also achieved current account surpluses of 5.6% of GDP (stagnation in net exports, re-exports of Chinese products to Germany).

B- The mechanisms of the sovereign debt crisis

The imbalances in the eurozone (public and private debt, external debt) exposed peripheral countries to the risk of a reversal in capital flows and became problematic when their sustainability was called into question. Indeed, the real estate and banking crises in Spain and Ireland and the Greek and Portuguese public deficits threatened to break up the eurozone. The sudden halt in foreign investment put an end to easy borrowing, and these countries are now facing public and private deleveraging constraints in a context of weak growth prospects, austerity policies, a sharp rise in unemployment, and a banking sector bailout that is very costly for public finances (Spain, Ireland).

II – Is a rebalancing currently underway?

The peripheral countries of the eurozone are under significant external pressure. The weakening of these countries’ export capacities is forcing them to restore their competitiveness at the cost of a contraction in domestic demand and « internal devaluations. » However, Germany, which carried out this devaluation in the mid-2000s, continues to enjoy excellent export competitiveness, making rebalancing more difficult for peripheral countries, whose exports are mainly destined for sluggish European markets.

A- Rebalancing through contraction of domestic demand and internal devaluation measures

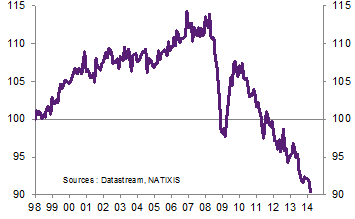

The peripheral countries of the eurozone are currently experiencing a loss of industrial production capacity, as can be seen in Figure 3 with the decline in manufacturing capacity since 2008. This is due to numerous bankruptcies and a slowdown in productive investment.

Figure 3. Manufacturing capacity (base 100 in 1998) in the periphery of the eurozone and Italy

Source: Natixis, Macrobond, BSI Economics

The objective of countries with deficits was to rebalance their current accounts by boosting exports through improved competitiveness. However, the combination of austerity policies, public and private debt reduction, rising unemployment, and sluggish growth led to a contraction in domestic demand and imports.

Between 2008 and 2012, the current account balances (these are current accounts, not budget balances, see Philippe Waechter, page1, graph 4) of Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain improved by 8 to 10 points of GDP. But these objectives were achieved at the cost of a long recession.

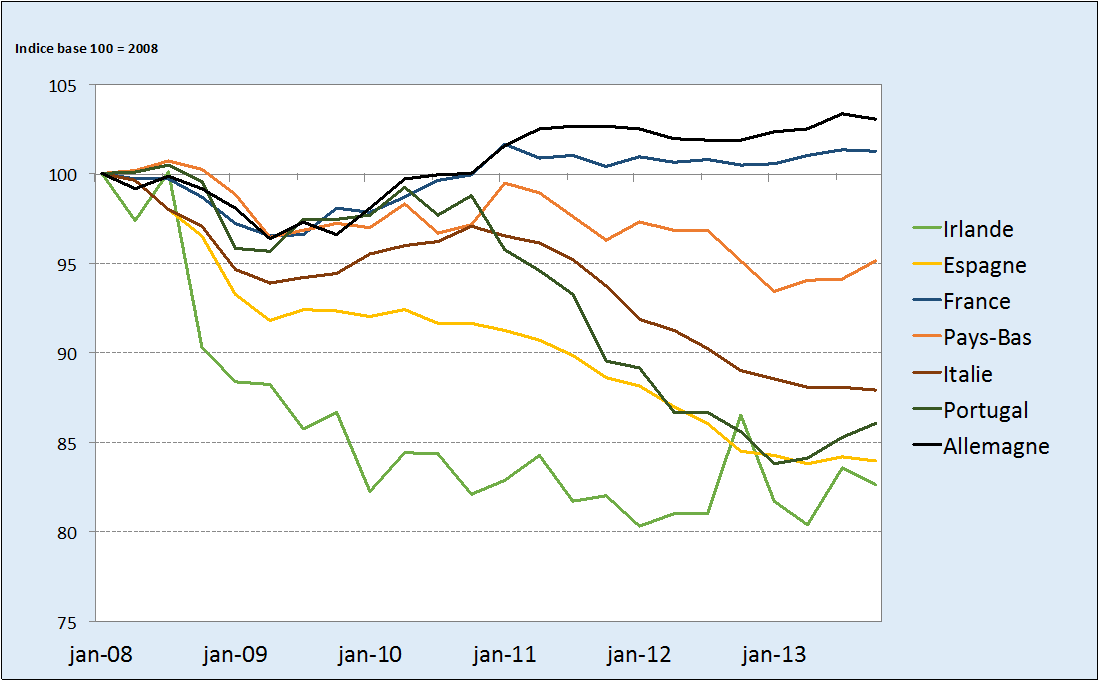

Looking at the evolution of domestic demand with 2008 as the base year, we can see that Germany has the strongest domestic demand. Ireland, Spain, Portugal, and Italy are experiencing very negative domestic demand trajectories, mainly as a result of austerity policies.

Figure 4. Evolution of domestic demand in the eurozone since 2008

Source: Author, Macrobond, BSI Economics

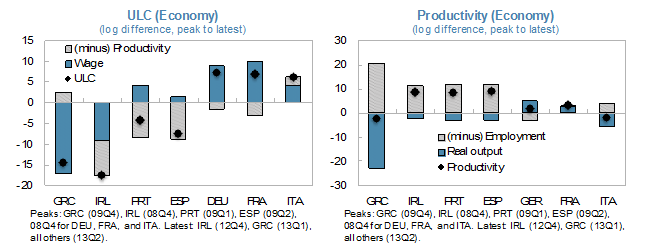

Between 2009 and 2013, the peripheral countries of the euro area also improved their price competitiveness by implementing « internal devaluations, » i.e., reducing unit labor costs through both wage adjustments and productivity gains.

Figure 5 shows the changes in unit labor costs in Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Germany, France, and Italy and the contributions of wages and productivity. With the exception of Greece and Italy, productivity gains played an important role in reducing unit labor costs, but were the result of job losses rather than growth in output. In Ireland, Portugal, and Spain, job losses have outpaced the decline in output, leading to higher productivity. In contrast, unit labor costs rose over the same period in France, Germany, and Italy, with productivity gains being very low or even negative in Italy.

Figure 5. Unit labor costs (left) and productivity (right) in the eurozone

Source: IMF, BSI Economics.

The rebalancing of current accounts is therefore mainly due to cyclical effects. The contraction in domestic demand caused by rising unemployment and downward pressure on wages is the result of « automatic stabilization » mechanisms and fiscal austerity policies. Without real structural improvements in the components of the current account balance, the return of economic growth in peripheral countries could lead to new external deficits.

B- But Germany remains more competitive

The large share of German exports to countries outside the eurozone and to faster-growing emerging countries has contributed to better export performance. In contrast, export growth has been weaker in peripheral countries due to both specialization in low-growth markets (tourism in Greece) and dependence on sluggish demand from the eurozone (Portugal, Spain, Italy).

Export growth for eurozone countries over the period 2008-2012 was mainly due to growth in demand outside the eurozone. Thus, Germany, which has a smaller share of its exports going to the eurozone, performed better in terms of exports (+4%) than Portugal (-0.5%), which exports 75% of its goods to the eurozone.

In addition, peripheral countries specialize in the production of lower value-added goods and are in direct competition with emerging countries for these products. Internal devaluations would therefore have limited effects on export growth, as competitiveness gains are made more in relation to countries with low labor costs (which are already very competitive on price).

The « illusory » rebalancing of the current accounts of the periphery does not seem sustainable in the medium term and therefore calls for more ambitious policies: in-depth reforms in the periphery to boost exports (moving upmarket, geographical diversification), and greater solidarity from surplus countries to rebalance competitiveness levels in the zone (higher inflation in Germany, for example).

Conclusion

Internal devaluations alone are not enough to rebalance current accounts between the center and the periphery of the eurozone. These countries have too weak an industrial base, which prevents them from significantly improving their exports, even with greater competitiveness.

To boost exports, peripheral countries must redirect production factors from non-tradable sectors to tradable sectors. These processes are slow, and their benefits will only materialize in the longer term.

As the peripheral countries of the eurozone are subject to external balance constraints and are seeing their industries contract, transfers from the center to the periphery are necessary both to reduce inequalities between the two regions and to finance investments that support potential growth in these countries.

Bibliography:

– Patrick Artus, How much federalism is needed in the eurozone? €600 billion per year should be transferred from the core to the periphery, Natixis, June 2014

– Ruben Atoyan, Jonathan Manning, Jesmin Rahman, Rebalancing: evidence from current account adjustment in Europe, IMF Working Papers, March 2013

– Clément Bouillet, Eurozone: towards economic (re)convergence?, BSI Economics, January 2014

– Thierry Tressel, Shengzu Wang, Rebalancing in the Euro Area and cyclicality of current account adjustments, IMF Working Papers, July 2014

– Philippe Waechter, Eurozone – towards a new equilibrium, Natixis AM, November 2013