Summary:

– The Eurozone does not meet all the criteria for an EMU.

– Neither do the other monetary zones in the world.

– The only criterion common to the other currency areas mentioned, but not to the Eurozone, is fiscal and budgetary integration.

– The euro is therefore not the problem. The real question is simply whether we want more or less integration.

It is often said that Europe’s problem is, above all else, the euro. Eliminating it, returning to national currencies, breaking up the monetary union and the power of the ECB (European Central Bank) would be the sacrosanct remedy to restore competitiveness to countries, and to France in particular, via the exchange rate. This is the goal of leaving the monetary union: to allow the government to use the weapon of devaluation as it sees fit. Add to this the fact that they could re-monetize the debt (i.e., print money to pay it off) and you have an explosive cocktail pushing for an exit from the Eurozone.

There is no question here of challenging these arguments, as they are partly credible. If France were to leave the zone tomorrow, a sharp devaluation would enable it to offer cheaper goods to the rest of the world, thereby increasing international orders and boosting the economy. Similarly, if tomorrow we regained control over our currency, we could print money to repay the debt and thus calm the financial markets to a certain extent. It should be noted, however, that the first argument is valid if and only if France leaves the eurozone alone, which is absolutely unthinkable because it would lead to other countries (Spain, Portugal, Italy) also leaving and using the exchange rate as a weapon. We would therefore see a « currency war. » The second argument would undoubtedly cause significant inflation, which is problematic for an economy. But that is not the purpose of this article.

The idea is to show that the elimination of economic policy options linked to the creation of the euro (devaluation, money printing) is not the problem, but that it is the degree of political integration in Europe that is the source of imbalances. The difficulty facing the eurozone, and Europe in general, is therefore much more basic, but also much more fundamental than the question of whether to keep or eliminate the euro. It is a question of deciding whether we want more or less integration. This decision will determine whether or not to leave the monetary zone. From this point of view, we believe it is absolutely necessary for opponents of the euro to be honest in admitting that they do not want monetary or political union and that they do not deny that leaving the euro would seriously disrupt European integration as we know it today. As for the defenders of the euro, they too must be honest in saying that it can only be maintained if integration continues in order to achieve a « United States of Europe. »

Optimal currency area and acceptance criteria

The introduction of the euro was decided legally more than 20 years ago. It is based on the theory of the Optimal Currency Area (OCA) and the criteria that derive from it. This theory was fully established after Kindleberger’s latest contribution in 1986. It was Mundell, in 1961 [1], who first put forward the idea that in the event of an asymmetric shock (i.e., affecting one region of the monetary area), there are three ways to absorb it:

– via the exchange rate (as we saw in the introduction, devaluation makes goods cheaper for the rest of the world, thereby increasing demand for our goods);

– via worker mobility (in this case, workers who lose their jobs in the affected regions leave to look for work where there are more opportunities);

-and finally through price and wage flexibility (in the affected regions, prices and wages must fall because there is too much labor supply—from unemployed workers—and not enough demand—from businesses, which are becoming fewer and fewer due to the shock).

Mundell therefore believes that if the exchange rate cannot be used (as is the case for a region of a country or a monetary zone), then the other two criteria must work.

In 1963, McKinnon [2] put forward the criterion of the degree of openness. The idea here is that if countries trade a lot with each other, then a fixed exchange rate (or, equivalently, a single currency) between these countries would have the definite advantage of reducing uncertainty. Floating exchange rates affect prices, and therefore expectations, and hinder trade. Ultimately, with floating exchange rates, it is impossible to know what the prices of imported goods will be tomorrow or the day after. It should also be noted that if economies are very open, the use of monetary weapons (i.e., devaluation) is dangerous since countries export but also import a lot. This will therefore lead to significant imported inflation (the prices of imported goods, such as oil, would automatically increase).

Kenen [3] emphasizes the criterion of economic diversification (1969). He believes that if a country has a diversified economy, it can consider forming a single monetary zone with other countries that are also diversified, since an asymmetric shock to one sector of the economy should not affect it too severely. This would inevitably reduce tensions on the single currency.

In the same year, Ingram and Johnson emphasized the need for financial integration [4]. Capital must flow freely within the monetary union. We can say straight away that this is the case for the European Union and for the vast majority of the world’s monetary areas. The interesting thing about this criterion is that it implies another: regional co-insurance (i.e., an integrated tax system), which in turn implies a centralized budget (i.e., a political union). These are the automatic stabilizers of a federalized monetary union.

Finally, Cooper [5] in 1977 and Kindleberger [6] in 1986 developed the criterion of homogeneity or convergence of preferences. They believe that countries must have the same visions of the future, the same desired macroeconomic balances, and the same desired trade-offs (such as that between inflation and unemployment, for example).

Let us summarize the criteria set out: worker mobility, price and wage flexibility, the degree of openness of the economy, diversity of production, financial and fiscal integration, and homogeneity or convergence of preferences. We would like to add two other « popular » criteria that seem credible from an economic point of view. We often hear that the euro cannot work because the levels of development (or wealth) of European countries are so different and divergent. It is worth noting that these are the criteria that come up most often, even though they are not present in the theories developed by economists. But it is true that we can question the possibility of uniting two countries with very different levels of development that are also diverging. Indeed, the economic policies that would be implemented there would be fundamentally different. So let’s incorporate these last two elements.

These criteria and the Eurozone

Let’s take a quick look at whether the Eurozone meets these criteria:

– Worker mobility: Whether we are talking about workers within the Eurozone or outside it, European workers are not mobile. To see this, we need only note that the only people who can move to another member state are those who speak the language of that country (or at least speak English fluently). This eliminates a very large proportion of the populations of European countries. The first criterion is therefore not met.

– Flexibility of wages and prices: as a general rule, European countries, especially those in the eurozone, have protective governments, which limits possible wage variations. Some countries at the heart of the crisis have lowered wages, but this is not the result of the free interplay of supply and demand. The second criterion is therefore not met.

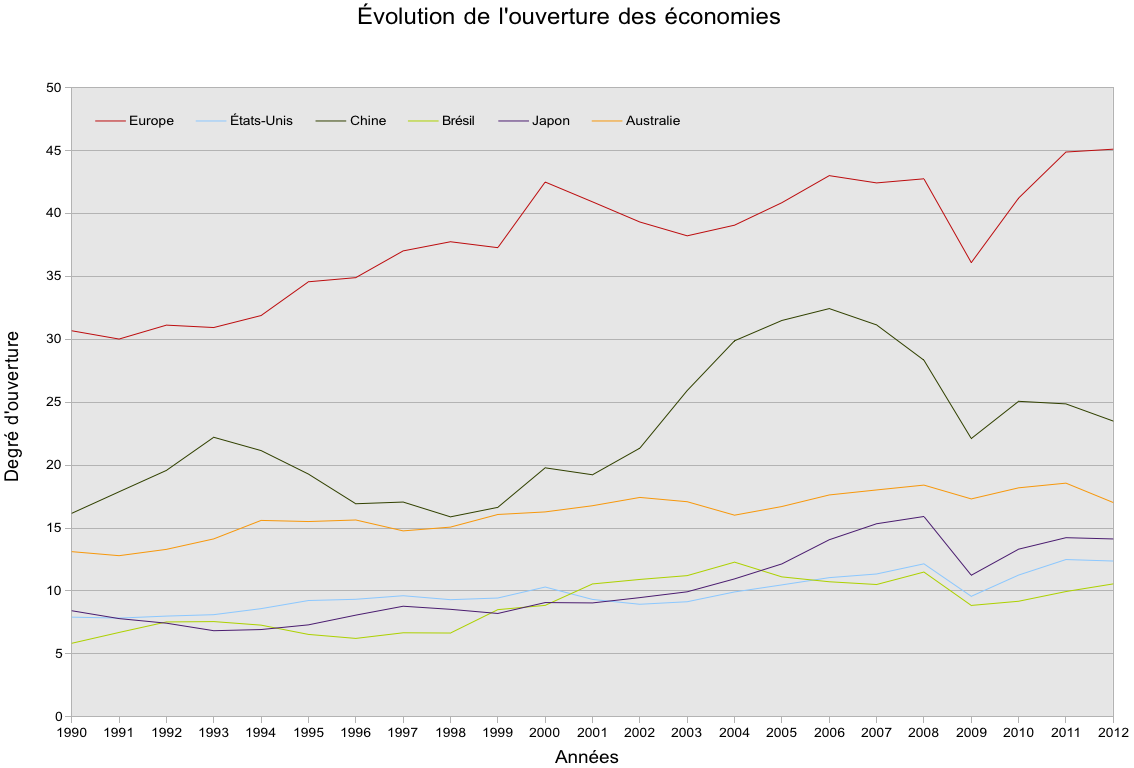

– Degree of openness of economies: the openness rate of European countries (calculated as follows: [(Imports + Exports)/2]/GDP) is much higher than that of other countries around the world (see the first graph below). It should be added that European countries’ trade is mainly focused on other European countries, particularly those in the eurozone. The third criterion is therefore met.

– Diversity of production: it is difficult to find clear figures providing this information, but it can be considered that European countries have economies that are sufficiently diversified to withstand an asymmetric shock to a single sector of the economy. Moreover, the levels of intra-industry trade between countries in the zone show that they produce a wide range of products. The fourth criterion is therefore met.

– Financial and fiscal integration: as already mentioned, financial integration is operational.It is also very well developed at the global level.On the other hand, fiscal integration (i.e., the establishment of a European tax and a global budget) is completely non-existent. The fifth criterion is therefore only partially met.

– Homogeneity, or convergence, of preferences: This criterion is extremely difficult to grasp and can become very subjective, so it should be made « neutral » in this analysis so as not to tip the balance in one direction or another. However, we can note that the repeated political crises within the major European decision-making bodies show that there is minimal homogeneity. Nevertheless, the Maastricht Treaty established strict convergence criteria. In this sense, we can say that while there is absolutely no homogeneity, there is probably convergence.

– The level of wealth of countries: it is undeniable that the countries of the Eurozone are far from having the same level of wealth. The seventh criterion is therefore not met.

– Convergence in wealth: taking into account the recent years of crisis within the Union, and therefore within the Eurozone, we can also say that there is no longer any convergence. The eighth criterion is therefore not met.

Are other currency areas EMAs?

The above list does not seem to favor maintaining the euro. Four important criteria are not met. But before jumping to conclusions, let’s take a look at the organization of a few other global currency areas. They have been chosen because they are stable and no one questions their currency. In this sense, they should be EMAs and therefore meet all the above criteria.

– Worker mobility: this is very high in the US, for example. But let’s take a less obvious example. When we were on the franc, France was a monetary zone, and its stability, like that of the US, suggested that it was an MZ. However, worker mobility in France is low. During the years when we had our own currency, no region, despite facing very different difficulties, wanted to secede on the pretext of returning to a local currency. And, moreover, the idea today of leaving the euro zone is to return to the franc throughout France, and thus to be a monetary zone. A monetary zone that would therefore not be an EMU.

– Wage and price flexibility: here again, we can take France as an example when we were using the franc. Labor market regulations are very strict in France, which prevents wages from adjusting in one region or another in the face of an asymmetric shock. However, once again, no one questioned the franc monetary zone, and no one would question it if we returned to it today.

– The degree of openness of economies: there is no need to find a counterexample, as the eurozone meets this criterion. It should also be noted that Europe’s degree of openness is by far one of the highest, ahead of the US and, above all, China and Brazil (see chart below: the European curve represents the average openness of member states).

Sources: Eurostat, BEA, Macrobond, BSI Economics

– Diversity of production: similarly, the eurozone meets this criterion.

– Financial and fiscal integration: the zone meets the first criterion, but not the second. There is no example to confirm this criterion: all other monetary unions, throughout history, have had an integrated fiscal and budgetary system.

– Homogeneity of preferences: as we said in the previous section, this element is difficult to measure. We will therefore leave it aside.

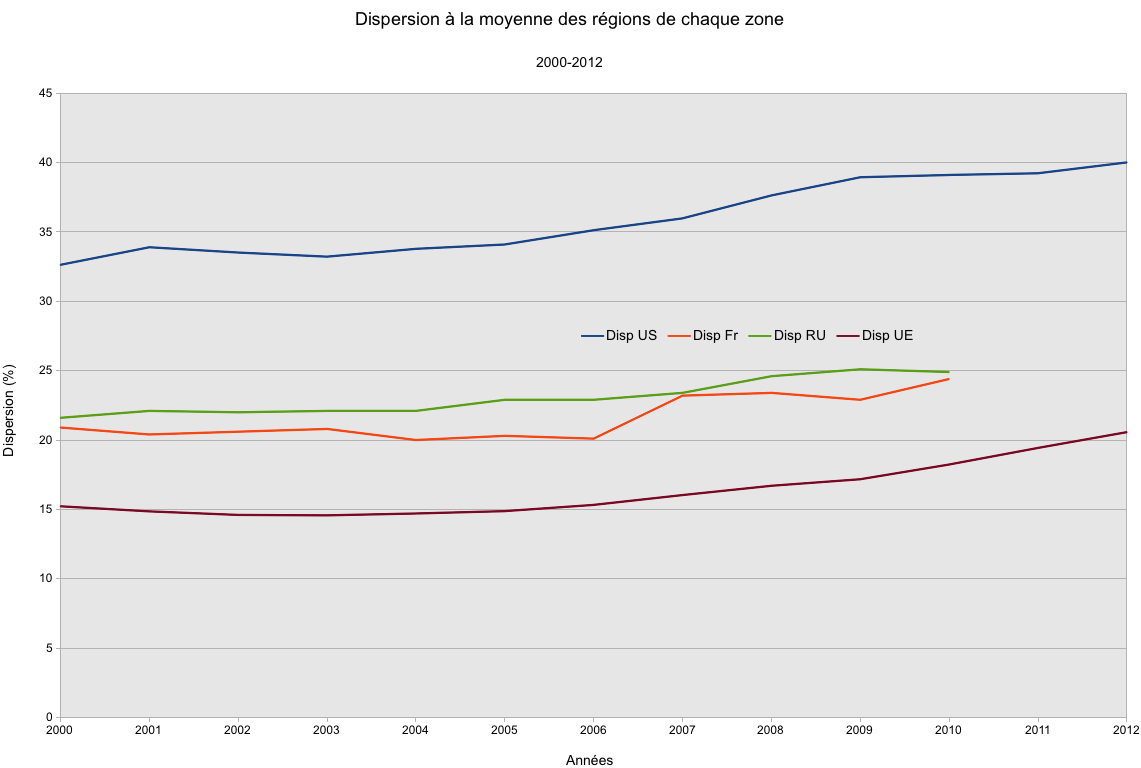

– Level of wealth (GDP per capita): the graph below shows a level of 15-20% of the European dispersion variable developed by Eurostat [7]. This same variable shows levels of 20 to 25% for France and the United Kingdom and levels above 30% for the United States. Thus, from the point of view of wealth, the members of the eurozone ultimately seem much less different than those of the United States and even those of the regions of the member countries.

– Convergence in wealth levels: this same graph clearly shows that in all currency areas, incomes by region tend to diverge, particularly in the US, which nevertheless has a high level of dispersion. This means that wealth is increasingly concentrated in certain areas.

Sources: Eurostat, BEA, US Census, Macrobond, BSI Economics

Conclusion

The eurozone does not meet the criteria of worker mobility, price and wage flexibility, fiscal and budgetary integration, and finally, homogeneity and convergence of wealth levels. However, there are examples of extremely stable monetary zones (such as the US, the UK, and France and Germany before they adopted the euro) that do not meet all these criteria either, and for which the question of eliminating their monetary union is not even being discussed.

Ultimately, there is only one criterion that the aforementioned currency areas have in common but the eurozone does not: fiscal and budgetary integration [9]. It therefore appears that the euro is not the problem. The real question is rather: more or less integration?

Why would a monetary union need fiscal and budgetary integration? Because fiscal integration puts in place what are known as automatic stabilizers, which protect regions from economic shocks.

The purpose of this article is therefore purely semantic. Anti-euro advocates seem to favor a Europe of Nations, while pro-euro advocates seem to be seeking to create a « United States of Europe, » two visions based on their own respective arguments.

Notes:

[1] MUNDELL R.A. (1961), « A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas, » American Economic Review, No. 4.

[2] MACKINNON R. (1963), « Optimum Currency Areas, » American Economic Review, vol. 53.

[3] KENEN P. (1969), « The Theory of Optimum Currency Areas: an Eclectic View » in MUNDELL R.A. and SWOBODA A., ibid.

[4] INGRAM J. (1969), « Comment: The Optimum Currency Problem » in MUNDELL R.A. and SWOBODA A.,Monetary Problems in International Economy, Chicago University Press.

[5] COOPER R. (1977), « Worldwide versus Regional Integration. The Optimum Size of the Integrated Area » in MATCHLUP F.ed, Economic Integration, Worldwide, Regional, Sectoral, London.

[6] KINDLEBERGER C. (1986), « International Public Goods without International Government, » American Economic Review, vol. 75.

[7] That is: Disp = 100((1/Y)(Σ|yi-Y|(pi-P))) where Y is the per capita income of the area, yi is the per capita income of the region, P is the population of the area, and pi is the population of the region.

[8] ZUMER F. (1998). Budgetary stabilization and redistribution between regions: centralized state, federal state. OFCE Review, 65(1), 243-289.

[9] It should be noted that there are three currency areas in the world similar to the euro area: the Franc zone (Africa), the Pacific Franc zone, and the Eastern Caribbean Dollar zone. They do not have a fiscal union, but the use of a single currency does not seem to be a problem. This could be the final argument to show that currency areas can exist without meeting all the criteria for a CEA. However, caution should be exercised when comparing these zones, as their global economic importance is very marginal (the main countries of the West African Economic and Monetary Union—Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Côte d’Ivoire—represent barely $50 billion in GDP, compared to $12 trillion for the eurozone).

References:

CMA: http://ethique.perso.sfr.fr/ZMO.html, http://www.melchior.fr/L-elargissement-des-criteres-q.3238.0.html.

Eurostat: http://epp.Eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/Eurostat/home/

US Census: http://www.census.gov/2010census/

Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA): http://www.bea.gov/