Abstract :

- By addressing the issue of growing wealth inequality, the Zucman tax seeks to establish greater fiscal equity. This tax proposal also comes at a time when there are calls for collective efforts to restore public finances.

- However, this proposal faces several operational limitations, both economically and legally.

- While the Zucman tax could lead to tax exile among the wealthiest individuals, the extent of this risk remains to be seen.

- The proposal faces legal barriers, particularly in its approach to taxing unrealized capital gains, which seems difficult to reconcile with economic reality.

- Rejecting it without proposing a credible alternative adds no value and does not address the issues it raises. On the contrary, this tax should serve as a basis for broadening the debate in order to explore several avenues for addressing wealth management companies (inheritance tax, national preference for investment, incentive mechanisms to link high net worth individuals and public services).

`

Download the PDF: Zucman tax—opportunities, fantasies, and alternatives— part 2

An initial note laid the groundwork for the analysis of the Zucman tax proposal. It shows that while the initial objective of strengthening tax fairness is legitimate, this tax faces significant operational limitations that make it unenforceable in its current form.

Thus, as a complement to Part 1, this second note seeks to explore alternative avenues for reflection and propose a renewal of the tax approach to asset holding companies in France. The objective is to remain as concrete and operational as possible, while keeping in mind the goal of moving toward greater tax fairness.

The approach of measuring unrealized capital gains in inheritances

One of the most interesting contributions to this debate is probably that of economist F. Ecalle, published inLe Nouvel Economiste.In this opinion piece, he highlights the weaknesses of the current system for taxing capital gains in the specific case of wealth transfer[1]. He proposes a relevant change to the valuation of unrealized capital gains when the heirs of a holding company are required to sell the shares of that holding company. According to him, « under the current system, an asset purchased by the deceased for $30, valued at $100 at the time of inheritance, and resold by the heir for $120, is only taxed on the capital gain of $20, and would be taxed on $90 if this reform were implemented ($70 at the time of inheritance and $20 at the time of sale). » . » F. Ecalle concludes his note with a similar question about tax allowances in the context of life insurance.

This proposal is more relevant than ever at a time when the economic logic behind inheritance exemptions appears limited and is at the root of growing wealth inequality (for more information, see this 2021 CAE study ).

Investment by holding companies, exemptions, and national preference

While the principle of the asset holding company system is not intended to be called into question in terms of its operation, the levels of exemption on the income derived from capital that it generates do raise questions (see Part 1). This specific taxation system is significantly out of step with the taxation system in force on income from work and income from capital earned by individuals or companies. The first step would be to review the level of exemption and lower it. This would certainly be a balancing act, but it is necessary in order to determine an optimal level of exemption that would not lead to tax exile and would not risk penalizing productive investment.

To this end, an investment criterion in the national economy could be introduced to determine the level of exemption. Upstream, it would be necessary to identify the profile of the assets held by holding companies in order to determine their weight in the financing of the French economy. Depending on this weight, it would potentially be possible to discriminate between holding companies according to their contribution to the French (or at least European) economy, both in terms of the amounts invested and the percentage of their total investments.

The lower the combined amount and percentage, the less relevant the logic of a high exemption seems to be and the lower the allowance could be, both for dividends and capital gains[2] linked to investments in foreign companies. The tax rate could then quickly converge towards 25% (the rate applied to companies).

Such a system would maintain the principle of tax advantages for holding companies while maximizing the incentive to favor a form of national preference. In this scenario, allowing tax advantages for holding companies seems more justified in that it is offset by a direct impact on the financing of the economy, ensuring, in principle, indirect tax benefits through the activity created.

Linking high net worth individuals to the financial needs of priority public services

There is probably untapped potential in France with regard to tax-exempt donations (the amounts of which are limited for both individuals and companies) and the definition of public interest organizations.

Given the decline in the quality and quantity of public services (education, health, security) despite high demand, a better connection should be established between large fortunes (particularly through holding companies) and public organizations. If it is not possible to make donations to ministries, the eligibility list should be extended to include high-priority public interest institutions (EIGHP), such as schools (not only in higher education), hospitals, research laboratories, etc.

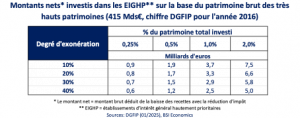

Rather than proposing a 2% tax on the wealth of the richest individuals, it would be better to channel funds to these EIGHPs by offering tax exemptions on a portion of the amounts allocated, proportional to the percentage of net wealth allocated. To maximize the effectiveness of the earmarking, EIGHPs should be ranked according to their needs in order to avoid a concentration of funding and promote a balanced allocation. A simplified calculation below provides a very broad estimate of the amounts that would be released under each scenario, based on estimates of the gross wealth of the households with the highest wealth in France according to the DGFIP[4].

In such a scenario, this mechanism offered a real « carrot, » but could also be supplemented by a « stick » to reinforce its incentive effect. Given the significant weight of real estate in the assets of the wealthiest households (nearly 36% according to INSEE), it would be conceivable to make the exclusion of real estate held through a holding company from the real estate wealth tax base conditional on a minimum participation in the scheme.

Such a scheme could be implemented on a temporary basis (for five years, for example) and would give the government some leeway to manage certain expenditures and move toward reducing its public deficit. Depending on the success of the scheme, as measured by the amounts collected, it could be terminated or adapted to other highly strategic needs.

Although unsuited to the economic reality (see Part 1), the Zucman tax highlights two key issues: tax fairness and public deficit management. These two challenges are at the heart of the avenues explored in this note. In order to restore public finances, the search for innovative solutions on the revenue side must be complemented by a similar approach on the expenditure side. A new impetus is all the more necessary in the national interest of establishing a more stable and serene economic and social climate.

Article written on 09/19/2025

[1] As mentioned above, capital gains realized within a holding company are only taxable when they are sold. They may never be taxed, typically when the owner of the holding company dies and transfers their shares to their heirs.

[2] According to Legifiscal, a 95% allowance is possible for a foreign subsidiary if the latter is subject to corporate income tax or an equivalent tax in its country (also under the conditions mentioned in footnote 3 of Part 1).

[3] Some of them are already eligible for tax-free donations and other forms of sponsorship: public and private non-profit higher education institutions, or those specializing in scientific and technical research, etc.

[4] Average assets of €10.2 million for 40,700 households, representing a total of around €415 billion.