Summary:

– Agriculture has been financial for several centuries; futures markets were even invented for agriculture.

– So what we now call the » financialization of agriculture » is simply an increase in its financialization.

– Today, 2% of agricultural market transactions result in physical delivery.

– Prices appear to be impacted by financialization.

The beginnings of financial agriculture

It is easy to forget that finance originated well before the second half ofthe 20th century. However, on closer inspection, we see that the first stock exchanges, similar to those we know today, were created in the 16th century (Antwerp in 1531, Lyon in 1540, London in 1571) [1]. This reminder highlights the fact that the current development of global financial markets is the continuation of a process that began centuries ago, often thanks to agriculture.

It is in this context that agricultural issues have been reemerging with force in recent years. Neglected for decades by the development projects of major international institutions because it was considered too unprofitable and not capital-intensive enough, agriculture has been completely abandoned in some countries (such as Malawi and Nigeria). It took » food riots » (2008) to raise awareness among leaders and bring the Millennium Development Goal (halving the proportion of the world’s population suffering from hunger) back to the forefront of development discussions.

But these riots had another effect: they blamed the financial markets, already overwhelmed by the subprime crisis. The idea was simple and the reasoning quick: international food commodity prices had skyrocketed so violently that it could only be the work of speculators thirsty for money and desperately seeking assets other than traditional financial products. The financial crisis had thus pushed investors to turn to agricultural assets, among other things, and their activity on the market alone had caused wheat prices to double and rice prices to triple [2].

The beginnings of financial agriculture

Let’s try to shed some light on the situation by going back to the beginning. Agriculture is a sector of the economy that is subject to the vagaries of the weather. Production capacity from one year to the next is therefore always difficult to determine, although modern techniques are helping to stabilize it. However, volatility is high because while supply fluctuates, demand always increases significantly, creating considerable tension: this is King’s law(or the inelasticity of demand for basic necessities). As a result, traders in this market (from farmers to end users) need to protect themselves against weather-related risks. This is why futures were invented: these are deferred delivery (or forward) contracts that can be traded on the markets. The first futures contracts generally date back tothe 17th centuryin the Netherlands, when the whole country was in turmoil over the Tulip [2] (an experiment that would end badly!). This system developed with the opening of the Chicago Stock Exchange in the 1840s.

The financialization of agriculture therefore began well before the industrial revolution but was limited by the restricted globalization of the economy. We are now witnessing the « new financialization of agriculture » with the emergence of index funds in this market. In 2004, the total value (which is constantly increasing) of agricultural futures contracts was $180 billion [3].

Recent developments in financialization

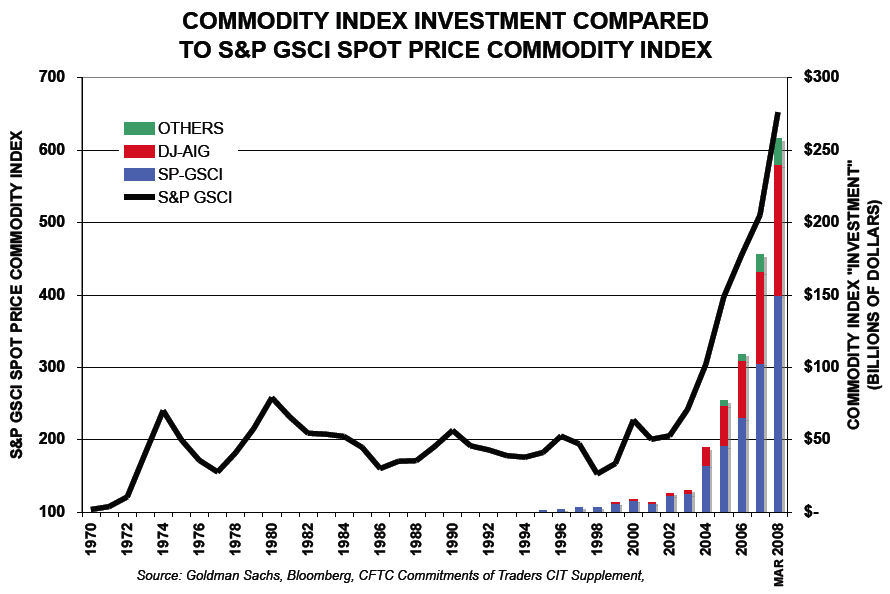

The first index fund was created in 1991 by Goldman Sachs (GSCI: Goldman Sachs Commodity Index) and then acquired by Standard & Poor’s in 2007. Its emergence was not disruptive in the early years because market regulations, inherited from the 1929 crisis, were still in place (albeit with some difficulty). In fact, the amounts invested in this fund (and subsequent funds) were relatively marginal compared to the market as a whole. However, deregulation allowed agricultural index funds to amass much more liquidity than before. It was this new situation that would disrupt the functioning of the market.

Technically, this product works in the same way as any other index fund. In other words, investors pool a sum of money that is used to purchase securities (in agriculture, these are necessarily futures contracts), which together form an index that is supposed to represent market trends. Thus, the portfolio held by the fund closely tracks price movements. The fund is used to take positions on the market, but it is also a long-term investment system. Once the fund has several billion dollars (thanks to investors), it buys a large number of futures contracts on the market. The agricultural market, which is characterized by a limited number of contracts, then finds itself in an « artificial » shortage, as the purchasing power of these funds is extremely high. The price of the contract must therefore increase, driving up the spot price [4] of the commodity.

In 2008, the US Senate requested an expert report on how the markets work. The following graph shows the evolution of investments in agricultural index funds since their creation in the early 1990s. The most telling figure is this: from $13 billion in 2003, investments rose to $260 billion in 2008, an increase of 2000% (some put the figure at $318 billion in July 2008) [5].

Only 2% of transactions on the market lead to physical delivery (i.e., the contract expires and the agricultural product is delivered to the buyer), while the remaining 98% are purely contract exchanges [6]. As we have already said, the agricultural market (like all markets) needs a minimum amount of speculation to ensure market liquidity. However, the proportion of speculation in relation to trading seems to be too high.

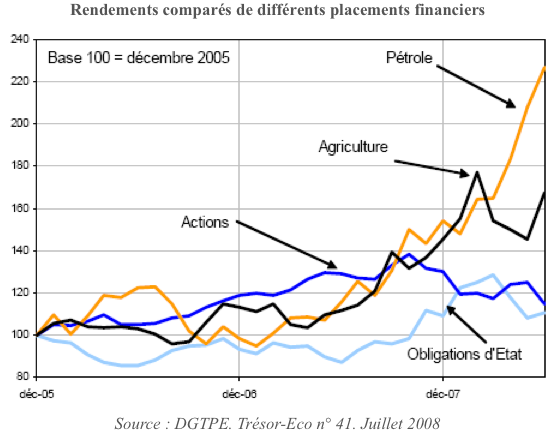

At first glance, one might wonder why investors are so attracted to agriculture. A study submitted to the French Senate [7] shows that the return on agricultural assets is now higher than that on corporate stocks and well above that on government bonds. In addition, it should be noted that agricultural commodity prices generally move in the opposite direction to other asset prices, allowing investors to diversify their portfolios.

The consequences of financialization

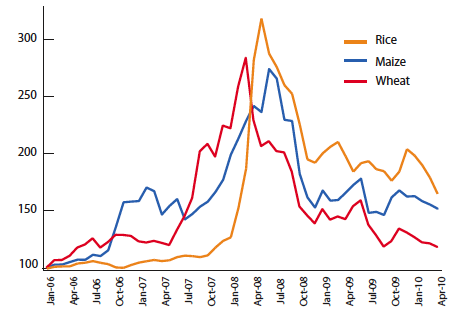

The early 2000s saw a change in the evolution of agricultural commodity prices. Prices rose, which is traditionally explained by increased global demand (driven by developing countries) and agricultural policies aimed at reducing stocks. Nevertheless, it is impossible not to notice that this date corresponds to the deregulation of markets and the rise, as we have seen previously, of index funds. A preliminary analysis of the evolution of prices for the main cereals may reinforce this intuition.

The rice market is less financialized than the wheat and corn markets for several reasons. Only 5 to 7% of production is traded, compared to 15 to 20% for corn and wheat. In addition, the major rice producers (China, India, Indonesia, Thailand) entered the market economy later. Above all, however, rice is a strategic cereal for maintaining global food security. While speculation is less significant in this market, increased demand and decreased stocks are therefore the main determinants of rice price fluctuations. As shown in the graph below [8], the prices of corn and wheat doubled and more than doubled, respectively, before the price of rice rose in January 2008. We can therefore assume that we are seeing the effect of speculation, which is more developed in the wheat and corn markets.

Changes in FAO price indices for the three main cereals

Source: FAO, Policy Brief No. 9, 2009

Conclusion

Scientific research has not provided a clear answer as to the effect of speculation on the agricultural world. However, one of the major consequences of this rapid financialization and the ensuing economic and social crisis is the desire of governments to re-regulate financial markets in general, and the agricultural market in particular. Several banks have closed their index funds for fear of tarnishing their image, and international bodies are insisting on regulating the market that is most sensitive both to human dignity and to the reduction of inequalities.

Reference:

[1] Montoussé, Bourachot, Renouard, Rettel. « 100 fact sheets to understand the stock market and financial markets »

[2] Laurent Curau. » Et krach, la tulipe » (And crash, the tulip )

[3] Financialization and volatility of agricultural markets: towards the definition of a new regulatory framework for derivatives markets

[4] The spot price of a commodity is the international price. In other words, it is the price determined on the financial markets by the interaction of supply and demand. It should be distinguished from the price of a futures contract, which represents the purchase of a specified quantity of goods and is directly influenced by speculation.

[5]Report to the US Senate by Michael W. Masters. 2008.

[6] Olivier De Schutter. « Food Commodities Speculation and Food Price Crises. » UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food.

[7] Report to the French Senate.

[8] Policy brief No. 9. FAO. « Price Surges in Food Markets: How Should Organized Futures Markets Be Regulated? »