The Eurozone and the end of the crisis: the difficulty of reform

Speech by Athanasios Orphanides (professor at MIT, former governor of the Central Bank of Cyprus) at the Banque de France on August 30, 2013

Summary:

– The Eurozone finally seems to be emerging from the crisis, but this recovery remains very fragile and weaker than that of the United States.

– The reasons for this gap lie in suboptimal crisis management and the difficulty of implementing reforms at the European level.

– The causes of the Eurozone’s stagnation can be found at the very heart of its decision-making process and the succession of elections in member countries.

The latest GDP forecasts for 2014 for developed economies seem to indicate an end to the recession for almost all European economies (to 1% in 2014, source: IMF) and stronger growth in the United States ( to 2.6%, source: IMF).This is reflected in the IMF’s upward revision of its growth forecast for France in 2014 at the beginning of October [1]. However, as Bénédicte Kukla pointed out, for the countries on the periphery of the eurozone,it is » a little too early to claim victory. » The divergence between the eurozone and the United States does not seem to be narrowing: while unemployment in the United States has fallen to 7.2%, it remains stagnant at around 12% in the eurozone, reaching peaks of 27% in Greece and Spain. The reasons for the persistence of such divergence are that the root causes of the Eurozone crisis have not been addressed: the major structural reforms that are needed, such as banking union, are slow to be implemented. This slowness is primarily due to a more expansionary monetary policy in the United States and the very structures of the Eurozone (governance issues, complex decision-making processes, etc.).

The deleterious dynamics of debt

Like the United States, the eurozone was hit hard by the subprime crisis, and many financial institutions suffered heavy financial losses or even went bankrupt (such as Northern Rock in England and Anglo Irish Bank in Ireland). Many were bailed out by their governments, including AIG in the United States and Fortis in Europe. In addition, many governments provided substantial support to their banking and financial sectors through credit lines or simply guarantees. Ireland, for example, had to inject the equivalent of 20% of its GDP to save its banking sector. But in doing so, governments set in motion a vicious circle of debt between the national banking sector and the government. In return for these generous bailout plans, financial institutions were asked by their governments to finance the national debt. Thus, any deterioration in the quality of sovereign debt automatically weakens the financial institutions, forcing the government to borrow even more to safeguard its financial sector, which in turn risks further deteriorating the quality of sovereign debt. This vicious circle of debt is the main reason for the persistence of the crisis, but it does not explain why the United States is faring better than the eurozone, as highlighted by the IMF’s growth forecasts.

GDP, IMF WEO, Estimate, Constant Prices, Change Y/Y (percentage)

Source: IMF, Macrobonds, BSI-Economics

« Questionable » crisis management

The main reason why the eurozone is struggling to return to growth (with the exception of Germany) is that a number of questionable decisions have been taken. Even before the crisis, the decision to give the eurozone a single monetary policy without a coherent fiscal policy limited its ability to respond to asymmetric shocks, as Paul Krugman had already pointed out. In addition, the Stability and Growth Pact, which sought to remedy this imbalance, was not very credible from the outset, as it only provided for sanctions in the event of excessive deficits and was also stripped of all credibility when it was not applied to France and Germany in 2005.

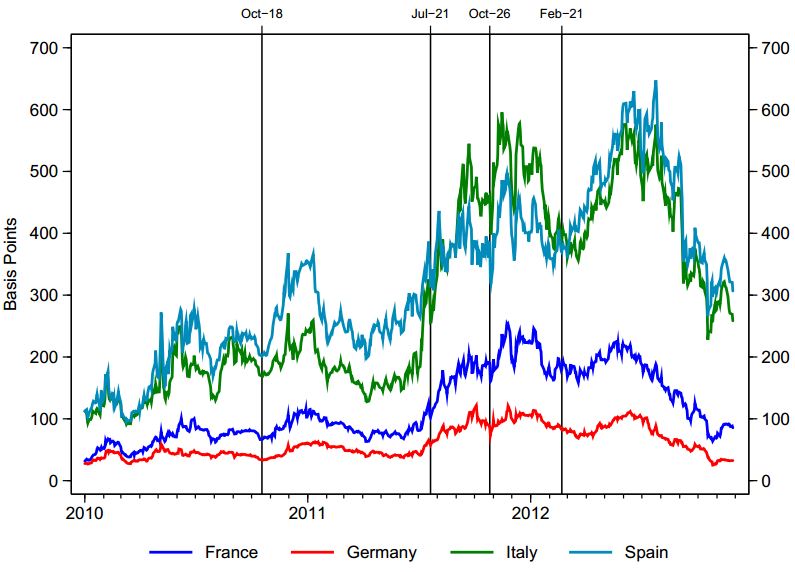

The management of the eurozone crisis itself has not always been optimal. For example, when European states reached an agreement in Deauville on October 18, 2010 (see chart below) to restructure Greek debt [2] (by 50%) and to have the private sector, which held Greek debt, bear part of the losses, this created « a precedent that greatly undermined the safety of European public debt, » according to Athanasios Orphanides. This decision fueled market mistrust of the debt of Eurozone countries (particularly Spain and Italy).

5-year CDS and European decisions

July 21, 2011: Eurozone summit, €158 billion in aid for Greece

October 26, 2011: Eurozone summit, restructuring of Greek debt, increase in EFSF capacity

February 21, 2012: creation of the ESM (European Stability Mechanism)

Source: Athanasios Orphanides, BSI Economics

Finally, the decision in March 2013 during the Cypriot crisis to draw on bank deposits, initially without taking into account the European deposit guarantee (set at €100,000), then targeting only amounts above this guarantee, only » added to the confusion » according to Athanasios Orphanides. Assets, deposits, which were supposed to be risk-free,became risky, fueling mistrust of the European economy and, in particular, of the debt of eurozone countries. The risk is that the Commission may want to replicate such a rescue plan for Italy or Spain, creating a risk of massive withdrawals of deposits to protect against the risk of loss. This would quickly destabilize an already very fragile banking sector. That is why the European Commission has strongly emphasized that this rescue plan was specific to Cyprus and could not be replicated under any circumstances.

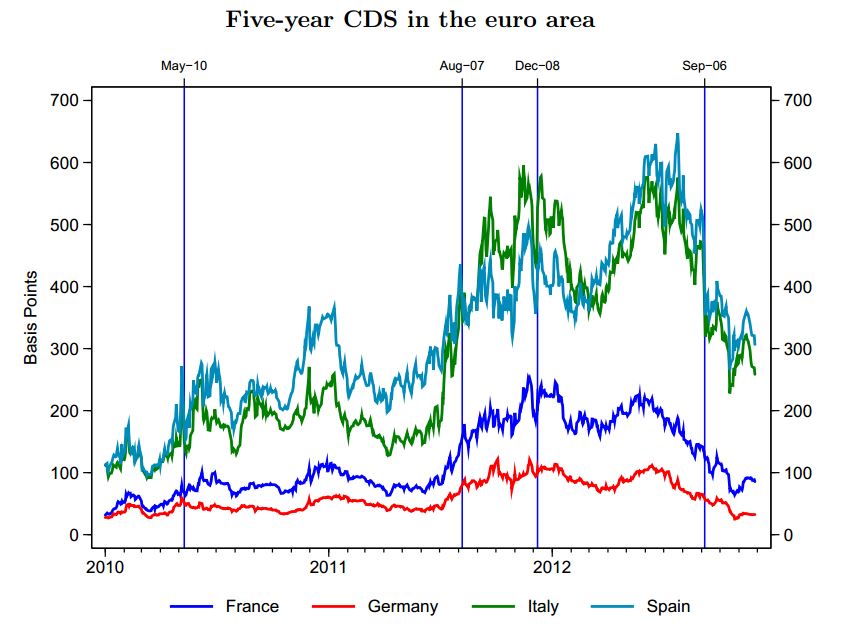

The ECB, firefighter of the crisis

Faced with the difficulties in the eurozone, the ECB has intervened on several occasions, both by lowering key interest rates and through so-called « unconventional » measures. On May 10, 2010 (see chart below), it launched the SMP (Securities Market Program) [3], which was extended on August 7, 2011 (see chart below), followed by LTRO (Long Term Refinancing Operations) [4] on December 8, 2011 (see chart below) and February 29, 2012, and finally the OMT (Outright Monetary Transactions) [5] on September 6, 2012 (see chart below), in order to respond to market fears and ease tensions (successfully) on the sovereign debt markets, as shown in the chart below.

5-year CDS and ECB interventions

Source: Athanasios Orphanides, BSI Economics

But through these operations, » the ECB can only buy time and can only address the symptoms of the eurozone’s weaknesses, which are primarily structural and political, » according to Athanasios Orphanides. For while the ECB may be able to calm the markets (see chart above) through its various actions, it cannot put an end to a crisis that is primarily structural (persistent imbalances, crisis of confidence, etc.). The ECB can carry out as many LTROs or sovereign debt buybacks as necessary, but without the establishment of a certain degree of fiscal solidarity within the eurozone and European supervision of banks to restore confidence within the eurozone, such a crisis will always be likely to reappear.The risk posed by the ECB’s actions is also that, by giving governments time to implement structural reforms, » the ECB is creating a perverse effect of procrastination on the part of governments, which are pushing reforms further and further back, increasing the overall cost of the crisis, » according to Athanasios Orphanides. The Banking Union is an example of this procrastination. Although the first draft was presented in May 2012 and a large majority of economists agree on its necessity to stabilize the European financial sector, which is caught in the vicious circle of debt described above, the project is progressing slowly. The main reason is the German government’s resolute opposition to the current form of the project. The German government opposes the expanded coverage of the banking union, which, without directly involving the Sparkassen, gives the ECB the possibility to intervene. In addition, the German government also opposes the mutualization of the resolution fund and would prefer a close association of national regulators. And while an agreement on a timetable for implementation has been reached, negotiations are still ongoing.

A biased decision-making process

The main source of this timidity in the eurozone lies at the very heart of the decision-making process. Many decisions require unanimity among members, which is becoming increasingly problematic with an enlarged Europe. This is evidenced by the failure to ratify the European Constitution in 2005, which was replaced by the Treaty of Lisbon. Any structural reform is subject to numerous negotiations and compromises, as was the case with the choice of coverage for the Banking Union, where an extensive position (all banks in the Eurozone) represented by France was opposed to a restrictive coverage (only systemic banks) represented by Germany.

Germany also has a unique feature in the form of the Constitutional Court in Karlsruhe. Any decision by the German government that affects Germany’s sovereignty must be reviewed by this court. This makes decision-making longer and more complex, especially given Germany’s weight. It was the Karlsruhe court that said « no » to Eurobonds, seeking to preserve German budgetary sovereignty. In June 2012, Karlsruhe criticized the German government for not involving the Bundestag sufficiently in its European policy decisions, which, by strengthening the parliament’s influence, also increased the importance of the 2013 German elections.

According to Athanasios Orphanides, the » succession of elections in the eurozone is one of the main factors contributing to the lack of progress, » especially as it is coupled with the rise of openly anti-European political parties. Governments therefore tend to postpone major European projects in order to increase their chances of re-election. The establishment of the Banking Union, for example, was postponed until March 2014, partly because of the German elections in October 2013. The management of the Cypriot crisis in the summer of 2013 was also influenced by the proximity of the German elections , Athanasios Orphanides points out . The decision not to bail out Cypriot banks, despite the limited cost compared to the Greek rescue plan (around €30 billion compared to more than €200 billion), can also be seen as a political choice. Although the implementation of a kind of bail-in (a condition for direct aid of €10 billion), drawing on deposits of more than €100,000, has the advantage of no longer relying on direct aid by seeking to « empower » the banking system, it cannot alone explain the decision not to resort to direct aid alone. Angela Merkel’s outgoing government having been heavily criticized for its handling of the Greek crisis, taxing deposits (most often of dubious origin) had the advantage of not providing direct aid, which could have been poorly received and reduced the chances of re-election. The upcoming UK elections in 2015 have already prompted David Cameron’s Conservative government to announce a referendum on the UK’s possible exit from the European Union before 2017.

Conclusion

The eurozone appears to be slowly emerging from the crisis, but this recovery remains very fragile and highly dependent on the implementation of major reforms such as the banking union and enhanced cooperation between its members. However, despite the increasingly proactive role of the ECB, reforms are struggling to get off the ground (negotiations on the Banking Union and the Single Resolution Mechanism are still ongoing). The main reasons for this are a very cumbersome and complex decision-making system and a series of elections that are pushing governments towards inaction.

References:

http://www.lse.ac.uk/fmg/events/financialRegulation/Athanasios-Orphanides-Slides.pdf

Athanasios Orphanides (2013) Is Monetary Policy Overburdened, BIS working paper

[2] Agreement established on October 26, 2011

[3] This program expands the range of assets accepted by the ECB as collateral for central liquidity loans.

[4] Operation during which eurozone banks were able to borrow without limit (for a total of €1 trillion) for a period of three years at 1%.

[5] Reform allowing the ECB to buy back sovereign debt, under certain conditions, in cases where a country has called on the European Stability Mechanism.