Summary:

– Tax evasion represents a loss of revenue for public authorities amounting to billions of euros.

– It stems from aggressive tax strategies employed by multinational corporations, which set up complex tax arrangements and exploit loopholes in the legal system.

– These tax optimizations are made possible by a more favorable business environment in certain areas, leading to tax competition between countries and paving the way for unfair tax competition between companies.

– The European Commission is pursuing its strategy to combat tax evasion, notably with a measure concerning the automatic exchange of tax information between countries.

Last March, the European Commission announcedmeasures to promote tax transparency. This set of measures is part of a broader action plan to combat corporate tax evasion, of which it is the first component.

Tax evasion: a global system

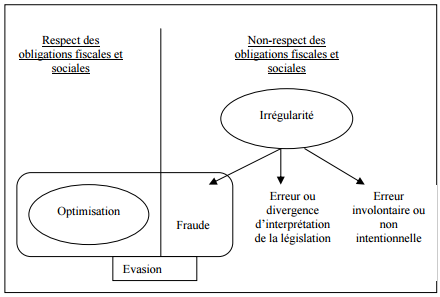

Tax evasion is linked to both tax fraud and tax optimization. Tax fraud is the deliberate behavior of an individual or company that breaks the law in order to evade taxation. It is therefore illegal. Tax optimization, on the other hand, consists of legal methods that use the tax system (special regimes, tax loopholes, etc.) to reduce tax liability. It therefore exploits the possibilities offered by legislation. Tax evasion lies at the boundary between these two concepts. The Council on Compulsory Levies, a body of the Court of Auditors, defines it as « all behavior by taxpayers aimed at reducing the amount of tax they would normally have to pay. If they use legal means, evasion falls into the category of optimization. Conversely, if they use illegal techniques or conceal the true scope of their operations, evasion is considered fraud. »[1]

Source: Council on Compulsory Levies

However, for the European Commission, a taxpayer evades tax when they use tax methods that it considers « aggressive » or exploit loopholes in a complex legal system while remaining within the legal framework. Thus, tax evasion as referred to in the Commission’s official documents is similar to tax optimization: « Tax evasion generally falls within the limits set by law. However, many forms of tax evasion are contrary to the spirit of the law, relying on a very broad interpretation of what is ‘legal’ in order to minimize a company’s overall tax contribution. Using aggressive tax planning techniques, some companies exploit legal loopholes in tax systems and asymmetries between national rules to avoid paying their fair share of tax. Furthermore, in many countries, the tax system in force allows companies to artificially transfer their profits to the territory of those countries, which has the effect of encouraging aggressive tax planning.[2]

A typical example of aggressive planning is when a multinational company charges a subsidiary an internal franchise fee in order to reduce the amount of profits it has to declare in France. In return, the franchise fee is paid to a structure created for this purpose, based in Luxembourg, for example. This allows the multinational to legally shift profits to other jurisdictions where taxation is more favorable, contradicting the principle of the law that taxes should reflect the place of activity. These practices, which have come to light in recent months, are suspected to have been implemented by several companies in order to avoid paying taxes to EU tax authorities.

These processes are carried out with the participation of certain countries that structure their tax systems in such a way as to facilitate this type of practice and thus attract profits to their territory. In particular, they may use tax rulings granted to multinational companies. A ruling is an advance confirmation by the tax authorities of how tax will be calculated, often at very favorable rates. These rulings are not a problem in themselves and are often used by Member States, but they can be misused to offer preferential arrangements and reduce tax, thereby encouraging large-scale tax optimization schemes. A company can therefore obtain a secret agreement with two different countries without either of them being aware of it, avoiding tax in both (this is known as « double exemption »).

Tax evasion involves many players around the world, including tax havens. Although difficult to quantify, there is consensus among public institutions that the cost of tax evasion and tax competition could be massive. The Commission indicatesthat « there are numerous reports and estimates on the scale of tax evasion in general and tax evasion by certain companies in particular, from tax administrations, NGOs, academia, and the press. There are no conclusive figures quantifying the extent of corporate tax evasion, but the general consensus is that it is considerable. One of the highest estimates puts the figure at €860 billion per year for tax fraud and €150 billion per year for tax evasion. Furthermore, these amounts do not generally include banking institutions.

Costs and challenges of tax optimization

Tax optimization therefore represents a loss of revenue for the state. It is also one of the proposals of economic theory on tax competition[3]. According to this literature, mobile bases, i.e., those that can migrate when taxes increase, generally capital, can change jurisdictions to move to areas where remuneration is highest. Thus, it is in the interest of each government to lower its capital tax rate in order to attract capital to its territory, but this imposes an externality on other countries: the erosion of their tax base. In the absence of cooperation, this externality leads to a race to the bottom, where the lack of cooperation results in a suboptimal equilibrium. Tax rates are pushed down and the financing of public goods is threatened. Empirical studies do not allow us to validate with certainty this theoretical result, which links the mobility of tax bases to the underprovision of public goods, particularly for the taxation of labor or savings.[4]. Indeed, it is difficult to distinguish between what is actually due to tax competition and what is due to the social contexts and policies specific to each country. On the other hand, the situation is clearer for corporate income tax (CIT)[5], since, as we have seen, multinationals are very sensitive to differences in tax regimes.

Tax evasion therefore jeopardizes the equitable distribution of tax revenue. Firstly, because tax competition means that the least mobile tax bases, i.e., those that cannot move to another country when taxes increase, such as unskilled workers as opposed to skilled workers, are likely to be taxed more heavily.This is another lesson from economic theory: since mobile bases can escape taxation, those that are less mobile are taxed more heavily.[6], raising issues of tax fairness. Furthermore, tax evasion undermines fair competition between companies, since those that use aggressive strategies and have the means to do so enjoy a head start over others. This runs counter to the principles of fair competition that govern European markets.

As a sign that policymakers are taking up the issue, in 2013 the OECD launched the BEPS project under the auspices of the G20 the BEPS(Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) project. It consists of an action plan with 15 recommendations at the international level, extending until the end of 2015. This plan aims in particular to take into account the new challenges facing tax administrations in a globalized economy, where a large part of the added value comes from the digital economy and intangible assets. Current tax systems are ill-suited to new modes of production based on intellectual property and dematerialization, hence the numerous loopholes exploited by the « GAFA » (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon).

The Commission’s strategy

The flagship measure of the tax transparency package is the automatic exchange of information between administrations. The idea is to oblige states to report all cross-border tax decisions, such as tax rulings, in a systematic and standardized manner (according to a fixed schedule, every three months).

As we have seen, tax evasion thrives on a lack of transparency and cooperation between administrations. Taken individually, each Member State has little or no information about the decisions taken by others, and does not inform them about its own activities. This is conducive to the spread of negative externalities, when one State erodes the bases of others by offering a preferential regime without reporting it.

For the time being, it is left to the states to declare any decision that they consider to have an impact on another, with the result that very little information is exchanged. An argument often put forward to justify this discretion is legal certainty or the right to business secrecy, which are therefore suspected of being misused to justify tax evasion. Automatic information exchange would prevent these reasons from being used to avoid sharing information, thereby removing any possibility of discretion or interpretation that allows states to conclude secret tax agreements. The question is whether such a measure actually threatens these rights: the trade-off is the potential loss of international competitiveness and a possible discouragement of investment.

The fight against tax evasion is not new to the Commission. One example is the 2011 Directive (2011/16/EU) on administrative cooperation, which establishes a legal framework and administrative procedures to enhance transparency. However, the exchange of information provided for in this framework is spontaneous and therefore non-binding. Since then, Directive 2011/16/EU has been revised in 2014 with Directive 2014/107/EU establishing the automatic exchange of a wide range of financial information and tackling banking secrecy.

The second part of the program, which is expected to be presented before the summer, will focus on corporate taxation. Focusing on issues of fairness and efficiency, the measures will notably relaunch the Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base (CCCTB) project.[7]. The idea is to subject eligible companies and groups operating in the EU to a single set of tax rules for calculating their taxable income. Once « consolidated, » this income would be valid throughout the zone and divided among national tax administrations according to a distribution rule. Such a system aims to combat the administrative burdens, duplication, and asymmetries between national regimes that a company faces when seeking to operate in Europe, which can deter investors. That said, the CCCTB project does not in itself involve harmonization of corporate tax rates: each country would be free to tax the portion of the tax base allocated to it, but on the basis of a more transparent tax base.

Conclusion

Progress in terms of tax cooperation is always difficult in Europe because it involves a transfer of sovereignty that can conflict with national preferences. As proof, any reform in the tax area must be agreed unanimously by the Member States, a rule that has been exploited by certain countries such as the United Kingdom, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands to block any measures for the automatic exchange of information. However, in a context where numerous revelations about the questionable tax practices of certain administrations are tending to promote transparency, the Commission’s initiatives should not meet with resistance in Parliament.

Notes:

(1) See http://www.ladocumentationfrancaise.fr/var/storage/rapports-publics/074000186.pdf

(3) Zodrow, G. R., & Mieszkowski, P. (1986). Pigou, Tiebout, property taxation, and the underprovision of local public goods. Journal of urban economics, 19(3), 356-370.

(4) See http://www.cae-eco.fr/IMG/pdf/cae-note014.pdf

(5) Devereux, M. P., Lockwood, B., & Redoano, M. (2008). Do countries compete over corporate tax rates? Journal of Public Economics, 92(5), 1210-1235.

(6) Razin, A., & Sadka, E. (1991). International tax competition and gains from tax harmonization. Economics Letters, 37(1), 69-76.