Summary:

– The CAP is the first and most successful of all common policies.

– It was initially based on two components: the organization of agricultural markets and their structural improvement (which is, however, marginal).

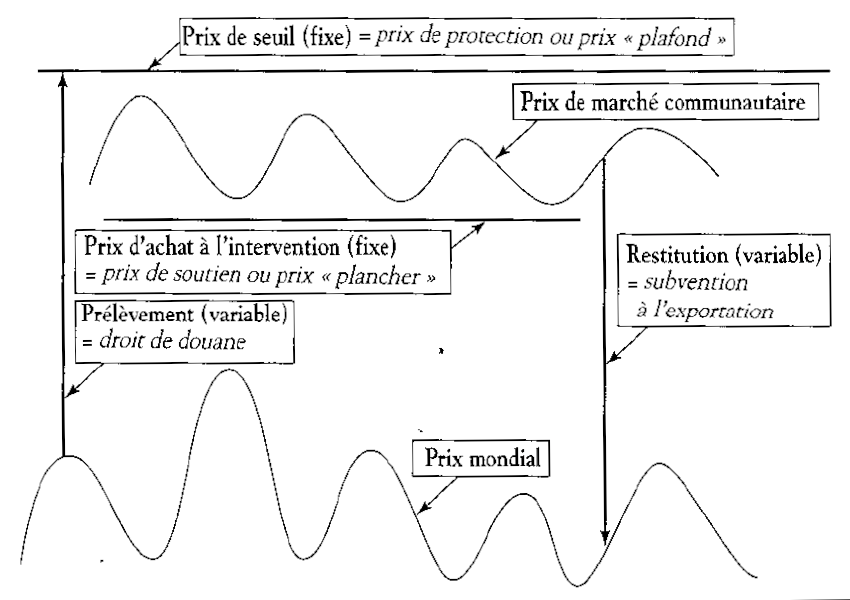

– Market organization was built around three tools: levies (or customs duties), guaranteed prices, and refunds (or export subsidies).

– Initially, the CAP worked remarkably well and quickly achieved its objectives, to such an extent that Europe entered a period of overproduction.

– In the following articles, we will see that reforms were therefore implemented to keep the CAP’s finances viable, but also to comply with international free trade agreements.

Thanks to the successful operation of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC, created in 1952), the governments of the member countries decided to create the European Economic Community in 1957. Agriculture was an integral part of this new European collaboration project.

Here, we will look back at the establishment of the Common Agricultural Policy, which was born out of a particularly strong desire on the part of France (the largest agricultural country in Europe). The aim of this policy was threefold: to increase productivity, stabilize markets, and ensure affordable prices for consumers. Here we look back at the period from 1957 to around 1984, and we will see how things developed in two future articles.

Historical context

In 1945, agriculture in the countries of the European Union was not only rudimentary, but also severely affected by the destruction caused by the war. Bombing had devastated roads, bridges and, more generally, a large part of the communication infrastructure. Farmers worked on land that was sometimes several kilometers apart. To ensure that households had a supply of milk, wheat (bread is a staple food in France and Europe), and eggs, farmers had to be multidisciplinary, which meant that yields were extremely low. In addition, countries were in constant short supply of food [1] and, in order to ensure their food security, they had to import most of their food from the US or its colonies at the time.

As soon as the common market was established (effective in 1959 and instituted by the Treaty of Rome in 1957), the beneficial effects on trade between members were impressive and called for a further reduction in customs duties. General De Gaulle made France’s acceptance conditional on the establishment of protection for the Community’s agriculture against international markets. International food prices were extremely low, which prevented French and European farmers from selling their produce internationally, but also on local markets.

The principles of a single agricultural market, Community preference, and financial solidarity were accepted at the 1962 Stresa Conference. The first refers to the single market and therefore the elimination of customs duties. The second emphasizes that it will be impossible to modernize agriculture if Europeans continue to consume foreign foodstuffs. Finally, the last principle truly established the common nature of the policy, as it required the management of the funds granted at the European level, completely detached from the situations in each country.

The three primary mechanisms of the CAP

After World War II, each country, with the help of the Marshall Plan, reinvested in its agriculture. Farms closest to large cities quickly acquired new technologies, but this support was not enough to boost European agriculture as a whole.

In fact, governments had two choices: either abandon agriculture or support it even more. Some countries in the community were tempted to abandon it because American foodstuffs were so cheap. Others wanted to support it to ensure food security (as in the case of France). However, none had the means to make agriculture a profitable sector of activity, as international competition was so fierce.

Europe therefore put three mechanisms in place, without requiring significant investment from member states. Although they have evolved considerably, these mechanisms still exist today. The diagram below (Figure 1) clearly illustrates these three principles.

Levies

The first mechanism is the levy. The idea is extremely simple: tax imports to make them more expensive than local prices. This breaks competition and allows European producers to have local outlets. However, food prices fluctuate greatly with climatic conditions. As a result, customs duties were flexible. Each year, the European authorities (the Commission and the agriculture ministers of the member countries) set a threshold price above the internal price of the community (determined by comparing internal supply and demand). Thus, the customs duty that a foreign exporter must pay to sell their goods in the community is the difference between the threshold price and their selling price. De facto, imports become more expensive than local products.

Guaranteed prices

The income that market protection guarantees farmers is not sufficient for them to invest. It is therefore added to the levy, the guaranteed price mechanism. The idea is also very simple: the community authorities set a minimum price each year. As soon as the internal market price falls below this price, the public authorities undertake to purchase, without any quantity limits, the production of farmers who wish to sell. This means that farmers know the minimum income they will receive and can therefore invest much more easily (this mechanism is now rarely used). It is partly financed by revenue from the levy (through the EAGGF: European Agricultural Guidance and Guarantee Fund; supplemented by contributions from Member States of around 50%).

Export subsidies

The EAGGF also finances export subsidies. From the outset, the Community anticipated that it would be preferable to export rather than buy at guaranteed prices (as this is more expensive) and that, as production increased, any surpluses would have to be exported. Thus, the CAP provides export subsidies that allow farmers to export at international market prices (which are much lower), but to recover the difference (between the international price and the domestic price).

The results of the CAP were very quickly extraordinarily positive. European production exploded. Wheat yields, for example, rose from 20 quintals per hectare in 1950 to 40 in the mid-1960s [2]. Farms became specialized and mechanized: draft horses disappeared, and dairy herds increased by 20%.

Figure 1: Principle of the CAP

Source: Olivier de Gasquet, (2002) Understanding our agriculture and the CAP.

In addition, since its inception (and increasingly so), the CAP has included a component of aid for structural renewal. Market players (states, cooperatives, farmers) knew that helping farmers to invest and increase their yields would not only require price guarantees. The infrastructure in rural areas was far too weak (today, this component, which we will return to in another article, aims to organize rural development). A very small part of the EAGGF (around 10% in 2001, known as the EAGGF Guidance Section) is thus allocated to farmers who want to invest, those who want to cease their activity due to lack of productivity, or those who want to undergo training. Nevertheless, most countries have implemented structural development and production reorganization policies in parallel with this component of the CAP.

Developments

International opposition

From the very beginning of the CAP, the US protested against the implementation of this policy, which it rightly considered protectionist. As part of the GATT negotiations, European countries had committed to using protectionist policies only in limited situations. However, the CAP went beyond the legal framework provided for this purpose.

European leaders argued that European agriculture needed to rebuild and develop after World War II, and they won their case after agreeing to a surprising demand from the US: they would not impose any customs duties on oilseeds [3]. At the time, these crops were rarely grown in Europe. However, they were already being used in meat production because soybeans, for example, are a very good source of protein. With European agriculture developing rapidly, the US anticipated that European demand for oilseeds would increase to feed their livestock.

Monetary problems

Apart from resistance from the US, the CAP did not encounter any major problems until 1969. That year, France had to devalue its currency. This was the first time that having different currencies within the community proved problematic for the CAP.

The price levels discussed above are set in units of account [4]. Following the events of 1968, the government decided to devalue the franc in August 1969 to restore the competitiveness of French companies. This devaluation was 12.5%. However, regulated prices remained the same as they were set in units of account for the entire community, so these prices increased by 12.5% in France. This was an unacceptable solution for the government, which could not allow food prices to rise so significantly.

To avoid this situation, the government devalued the franc against all currencies, but not against the unit of account. As a result, agricultural prices, which were governed by this unit of account, remained unchanged.

However, this solution posed another problem: as agricultural commodity prices did not increase and the parity of the franc fell by 12.5%, commercial transactions carried out in francs against the Deutschmark (for example) gave French farmers a 12.5% advantage over their German (and European) competitors. This was unacceptable to their partners.

To reduce this, the Commission decided to impose a tax on French agricultural exports to its European partners and a subsidy on agricultural imports from partners to France. This was the first major complication of the CAP.

Two months after this decision, Germany decided, for a variety of reasons, to revalue the mark (October 1969), which created the opposite situation. The Commission therefore implemented the reverse system. In the years that followed, agricultural prices rose in France, fell in Germany, and the single price was reestablished. But as soon as it was reestablished, the US stopped the convertibility of the dollar into gold, which led to the end of the Bretton Woods agreements (1971), taking with them the fixed exchange rates of currencies. In fact, each European country became a separate zone with compensatory amounts on imports and exports to maintain the fixed parity with the single price. This new situation created enormous distortions between countries whose currencies appreciated and those whose currencies depreciated. The compensatory amounts were paid without really taking all the factors into account, leading to the subsidization of German exports and the curbing of French exports, for example. This problem was amplified by budgetary considerations.

The budget

As mentioned above, the CAP is financed by the EAGGF, which draws its funds from levies and contributions from member countries (which is still the case today). These contributions represent 1% of the value of VAT collected by each partner. In fact, highly industrialized countries are larger contributors than others. Thus, Germany has been the largest contributor since the creation of the CAP.

The German authorities’ response to this situation was not to try to change the rules, but rather to use the CAP to drastically develop their agriculture and thus collect a larger share of the total EAGGF funds. This behavior was shared by all countries, as they all wanted to minimize their share of the cost of this policy.

This contributed to straining the fund’s finances, which were already under pressure from the growth in agricultural production. When the CAP was introduced, expenditure was low compared to revenue. However, the increase in production forced the authorities to buy more and more at the guaranteed price, which became increasingly expensive. In addition, farmers exported unsold produce, which also cost a lot of money since the international price was lower than the guaranteed price.

These two factors forced the authorities to review the operating principles of the CAP. In 1988, they began by establishing a guideline for the evolution of the budget allocated to the EAGGF. From that date onwards, it could not increase by more than 74% of the Community’s GDP growth rate.

Overproduction

The root of the problem lies here, as we have already mentioned: the CAP was a victim of its own success. Production increased remarkably in the early years of the agricultural policy. Of course, we must not forget the Marshall Plan and the agricultural organizations in each country, which played a very important role even before the CAP was established. But the guarantees that this policy gave to farmers enabled them to invest heavily and thus ensure food security and even exceed the needs of the community.

And this is where we see the end of the system. Ingenious mechanisms can only function at low cost if production does not chronically exceed demand. Unfortunately, this was the case in the early 1980s in several agricultural sectors (such as dairy production) and was later followed by others (such as cereals).

Increased spending and decreased revenue (as imports declined) caused finances to spiral out of control. But the political cost was so high that decision-makers refused to tackle the issue head-on. Nevertheless, the 1984 European Council, under the leadership of France, which held the presidency at the time, already raised the important issues, and everyone knew that something had to be done.

Conclusion

The early days of the CAP were a real success. Within twenty years, European agriculture became one of the most productive in the world. This was despite significant differences, as Europe is far from being a homogeneous entity.

However, as we will see in a future article, the promising beginnings, although marred by a few crises, quickly gave way to a situation of overproduction that distanced farmers from the decision-making process and significantly complicated the Common Agricultural Policy.

Notes:

[1] Rationing was maintained until the early 1950s.

[2] Olivier de Gasquet, (2002) Understanding our agriculture and the CAP.

[3] Oilseeds are plants rich in lipids and widely used in livestock feed (soybeans, rapeseed, etc.).

[4] The unit of account is in fact a fictitious currency. At the time, no one actually said so, but the unit of account corresponded to the dollar. In other words, guaranteed prices were set in dollars and then converted into each national currency to pay producers. Later, the ecu became the Union’s unit of account, and finally the euro.

References:

– Olivier de Gasquet, (2002) Understanding our agriculture and the CAP.

– Christiane Lambert, (2009) How food prices are formed from producer to consumer.

– European Union website, http://europa.eu/pol/agr/index_fr.htm

– Ministry of Agriculture website, http://agriculture.gouv.fr/pac-soutiens-directs-et

– « Il était une fois la PAC » website, http://www.iletaitunefoislapac.com

– Nicolas-Jean Bréhon, (2010) The CAP in search of legitimacy. Study available on the Robert Schuman Foundation website.

– Jean-Pierre Butault, (2004) Agricultural subsidies: theory, history, measurement