Summary:

– 1984 marks a turning point for the CAP, as it is synonymous with milk overproduction: introduction of quotas

– The remedy led to overproduction of beef and then cereals

– International attacks within the GATT multiplied

– The CAP was reformed once again in 1992, then for Agenda 2000, and again in 2003

– It no longer has much in common with the original CAP, but it includes an important sustainable development component

A previous article presented the beginnings of the CAP (Common Agricultural Policy). Its system was simple at the time, involving the introduction of import levies, guaranteed prices for any surpluses, and finally export subsidies.

This policy had unexpected results, as not only did it revive European agriculture through unprecedented modernization, but it was also largely financed by import levies.

After 1984, overproduction threatened the viability of the CAP. In addition, the number of countries benefiting from it increased with the enlargement of the Union. Finally, those responsible did not dare to reform the policy head-on. They therefore made a few adjustments that added layers of complexity but postponed the inevitable: implementing reforms that were as profound as they were brutal.

Until 1992

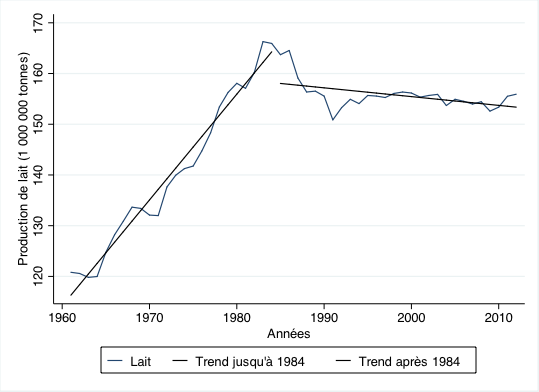

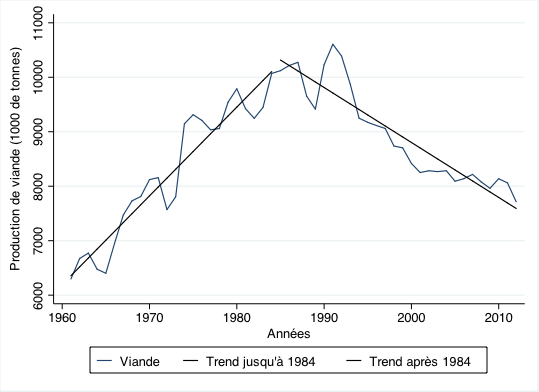

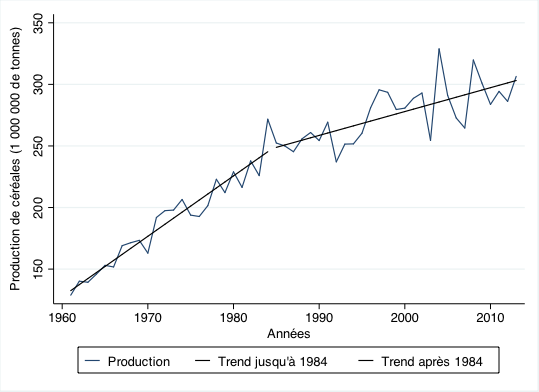

Overproduction did not immediately affect all agricultural sectors. However, as shown in Figures 1, 2, and 3, milk, beef, and cereal production increased significantly until 1984. Overproduction occurred most rapidly in the milk sector (as early as 1984).

The authorities then introduced a tax on milk producers, stopped counteracting inflation, limited the possibility of purchasing at guaranteed prices to certain months of the year, and reduced the profitability of storage (as remuneration for this was also based on amounts determined by the public authorities). In addition, the European Agricultural Guidance and Guarantee Fund (EAGGF) delayed its payments when purchasing goods and tightened the quality criteria for the foodstuffs it purchased, all of which took place amid monetary turmoil that limited the ability of all stakeholders to understand the situation.

These minor reforms did not enable the CAP’s finances to return to a viable path. In 1984, when the milk market produced an unprecedented quantity, it became necessary to overhaul the system to enable it to continue: this led to the introduction of milk quotas.

Production limits

The introduction of quotas on the volume of milk produced by each farmer meant that the objective of the policy changed: the aim was no longer to increase production, as had been the case until then, but to stabilize it.

To limit farmer discontent, governments reorganized the entire industry. Milk producers were encouraged to close their farms if they were close to retirement or if their farms were not productive. The production rights of these farms are then bought back by governments and redistributed to all other producers. As a result, production on each remaining farm increases, but overall production decreases thanks to milk quotas.

Graph 1: Evolution of milk production

Sources: FAOSTAT, Author, BSI Economics

Unfortunately, the successful and accepted implementation of these quotas led to overproduction in the cattle and cereal sectors (1988). As dairy farms closed, animals were sent to slaughter and some farmers decided to produce cereals rather than leave their pastures fallow. Milk producers, meanwhile, were encouraged to increase their yields (agricultural intensification is still ongoing), which led them to stop using grass as the staple feed for their animals and switch to more protein-rich nutrients (such as corn or soybeans). They, too, began to cultivate their pastures. As a result, cereal and meat production is increasing.

In the cattle farming sector, it was decided to reduce guaranteed prices [1]. Farmers’ incomes therefore fell accordingly. This caused significant discontent, forcing governments to introduce direct subsidies for farmers. This would later become common practice.

Graph 2: Evolution of beef production

Sources: FAOSTAT, Author, BSI Economics

In the cereal sector, countries could not agree on the course of action to take, particularly Germany and France. The former wanted to limit production, roughly along the lines of the milk quota system, while the latter believed that its producers could easily cope with a fall in prices by increasing their production. Ultimately, the solution implemented has two components: budgetary stabilizers (the functioning of which will be explained below) and voluntary land freezing (i.e., set-aside). In practice, the second part is very difficult to implement because it means convincing farmers that it is better to produce less. Nevertheless, it is the beginning of the implementation of compulsory set-aside.

Figure 3: Changes in cereal production

Sources: FAOSTAT, Author, BSI Economics

Financial quotas & Budget stabilizers

When the dairy crisis erupted and quotas on volumes (production) were introduced, the European Council applied the financial quota system to the oilseed sector. As we mentioned in the previous article, this sector is not protected by the CAP due to pressure from the US. However, Europe still wanted to develop this type of agriculture with the help of production subsidies.

In fact, this area is extremely costly for the Community because competition is fierce, especially as the amount of land under cultivation increases. It was therefore decided to set a purchase budget at a guaranteed price and to reduce the price once the budget was exceeded.

This system was extended to all sectors of the CAP after the European Council meeting in February 1988. In addition to quotas on milk volumes, reductions in guaranteed prices for beef and the freezing of cereal land, price quotas were also introduced. The agricultural guideline was introduced, preventing the EAGGF from receiving more than ECU 27.5 billion between 1988 and at least 1992, with annual growth not exceeding 74% of the Union’s GNP growth rate [2].

The generalization of quotas was a decision that ran counter to the prevailing liberal thinking of the time, which held that the market was the best regulator in agriculture as elsewhere. The European Commission pushed for the use of market regulation as much as possible, as it was less costly. Although the European Council remained committed to dirigisme at the time, the 1992 reform did not follow this path.

The 1992 reform

International context

From the moment the CAP was introduced, the US disagreed with it and only accepted it on condition that customs duties on oilseeds were eliminated. However, the smooth functioning of the CAP quickly reduced European imports, reigniting tensions within the GATT (the US, Canada, and Australia called for the dismantling of export subsidies). The European Community nevertheless stood its ground.

Four years later, all the protagonists agree to initiate a new round of negotiations within the GATT: the Uruguay Round. These negotiations begin auspiciously for the Community, as the roadmap for the agricultural negotiations is very clear: if Europe has to make concessions, so must the US and other major agricultural countries. However, unlike the US, the Community did not take any initiatives. In 1989, the US struck with a proposal calling for the outright dismantling of the three pillars of the CAP. The Community was caught off guard and responded hastily to this proposal, mainly by asking for an increase in customs duties on oilseeds in exchange for the elimination of levies. This meant that it was endorsing a possible reduction in customs duties.

The final stage of these negotiations was the ministerial meeting in December 1990, where the protagonists were supposed to refine the negotiations and sign the agreement. But the US demanded more and more. The Commission, which had a mandate to negotiate and yet wanted more than anything to reach an agreement that would restore balance to the Community’s finances, could not accept all these demands. The negotiations on agriculture were not concluded. But the European Commissioners knew that a comprehensive reform had to be set in motion.

The content of the reform

First of all, it should be noted that the draft reform comes from the Commission, and the Commission alone. Believing that governments are too subject to agricultural lobbies, it decided to develop a reform project in the utmost secrecy. The first versions circulated following the 1990 ministerial meeting.

Ultimately, this reform was of paramount importance in the design of the CAP. The aim was to reduce the level of guaranteed prices (by 35% for cereals and 15% for beef, for example) and to pay subsidies directly to producers to compensate for losses. These subsidies were paid per hectare or per animal.

In addition, there is no longer any question of using variable levies, but rather of introducing fixed customs duties, which are by nature less protective.

The CAP is therefore designed along the same lines as US agricultural policy: support is no longer based on prices, i.e., a subsidy paid for by consumers, but on income, i.e., a subsidy paid for by taxpayers.

Agenda 2000

Context

In 1994, the members of the GATT finally signed a comprehensive agreement. Many twists and turns hampered the drafting of the final document, particularly on the European side, where the Commission once again took liberties that the governments could not accept. This agreement had a direct and significant impact on agricultural policy, as it provided for the elimination of compulsory levies, a 36% reduction in fixed customs duties over five years to replace these levies, and a 21% reduction in subsidized exports over six years.

The « mad cow » episode in 1996 and the dioxin chicken episode in 1999, and more generally the problem of animal meal, undermine the idea of efficient and healthy European agriculture. These episodes alerted public opinion, and by extension governments, forcing the Union to address these issues, which are closely linked to public health. Similarly, the Union’s institutions must tread very carefully when dealing with the issue of GMOs (genetically modified organisms). Here again, public opinion will play a decisive role. Finally, Europe is planning a major eastward expansion. This will inevitably disrupt the management of agricultural issues, especially since the new countries have poorly industrialized economies. This is forcing the EU to reorganize the small structural component of the CAP (see first article) by creating the « second pillar » (discussed below).

Finally, in 1996, the US launched a major reform of its agriculture (the FAIR Act), which provided for the elimination of all production support. Subsidies were initially put in place, but they were intended to be temporary and to allow farmers to gradually get used to market mechanisms. In return, farmers were free to produce whatever they wanted, in whatever quantities they wanted.

The content of the reform

The Commission and many national decision-makers believe that the seemingly far-reaching US agricultural policy reform will render the latest GATT negotiations obsolete. The basis of the US reform is the decoupling of subsidies, which will become the spearhead of the new CAP. The idea is simple: rather than subsidizing a particular type of crop and a specific quantity, subsidies will be given per acre, regardless of the crop.

Ultimately, the Agenda 2000 reform will not completely eliminate the subsidies as they were initially set up. But they will be drastically reduced in favor of direct aid.

The guaranteed price for cereals will thus fall by 15%, and that for beef by 20%. At the same time, aid per hectare will increase by 16% and aid per animal by 56%. These amounts are also expected to increase in subsequent years.

This reform therefore goes further than that of 1992 in bringing the price obtained by farmers closer to the world market price. The spirit is the same: not to act on the price, but to subsidize the farmer to produce. It is a bit as if farmers were becoming civil servants of the Union. On average in France, subsidies accounted for 18% of farmers’ income in 1991 and more than 80% in 2006; on average in the EU, they accounted for 60% [3,4]. This is to such an extent that a third of European farmers would disappear in less than a year without these direct payments [5].

It should be noted, however, that refunds (export subsidies) have not been eliminated, and still exist today (although it is the Commission that decides which types of goods are eligible for refunds).

Finally, the Agenda 2000 reform created the second pillar of the CAP, which aims to develop regions that are lagging behind, convert the activities of regions in difficulty, and take into account the management of rural human resources (where unemployment is often high). It remains marginal, since of the €40.5 billion per year spent by the EAGGF (planned for the period 2000-2006), only €4.3 billion is allocated to this second pillar [6].

Mid-term reform: 2003

The Agenda 2000 reform was intended to provide a framework for the CAP until 2006. However, a mid-term review was decided upon in 2002. This led to a new reform in 2003.

Context

The Common Agricultural Policy complies with WTO agreements, and Agenda 2000 made it possible to maintain a satisfactory level of short-term EAGGF expenditure. However, since the « mad cow » and dioxin-contaminated chicken scandals, the European authorities have wanted to reorient agriculture towards sustainable development.

Content of the reform

This reform is, of course, an opportunity to reduce the guaranteed prices of certain commodities (rice, for example) and to cut other subsidies. However, the focus of the reform is on the method of allocating subsidies to farmers, which involves compliance with specific environmental standards. The Single Payment Scheme (SPS) is being introduced and aims to completely decouple subsidies from the type and level of production on the farm.

However, this reform stipulates that the level of decoupling on a given farm is to be decided by the states. This means that the decision on the type of crop is not left entirely to the farmer, thereby avoiding the risk of only one commodity being produced over a large area.

The Commission makes these SPS payments conditional on the implementation of environmental standards in the broadest sense. This concerns respect for the environment (water, soil, trees) and animal health (appropriate food, decent breeding conditions).

It also provides for the strengthening of the second pillar, which will enable farmers to meet standards and thus respect the environment. Finally, it provides for a balanced budget until 2013 by using subsidies to farmers as an adjustment variable.

Conclusion

Following the overproduction of the 1980s, which led to the EAGGF budget slipping, the European authorities, followed by the Member States, decided to reform the CAP to bring it closer to the organization of US agricultural policy.

The reforms of 1992, Agenda 2000, and 2003 were thus aimed at bringing farm-gate prices closer to market prices. Nevertheless, the EU has set up a systemof direct aidto farmers. In fact, these reforms cannot be described as liberal, since public intervention is still fundamental to the organization of European agriculture, as it is in the United States and all other major agricultural powers (Canada and Australia, for example).

On the other hand, the 2003 reform seems to open up a new era in agricultural policy, as it incorporates environmental considerations to a large extent. However, two things are worth noting. First, farmers’ incomes have not increased significantly in the EU since the CAP was introduced. This means that direct aid is absolutely necessary to maintain profitable agriculture. Second, developing countries will not remain inactive for long in the face of the distortion of competition caused by the payment of direct aid.

Notes:

[1] Because it is impossible to set quotas since meat production is highly storable and can even be produced on demand (since animals can be slaughtered at any time). Furthermore, animals do not necessarily pass through a slaughterhouse, which limits the possibilities for control, unlike milk, which must pass through a dairy.

[2] European Parliament, Financing the CAP: the EAGGF. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/facts_2004/4_1_6_fr.htm

[3] INSEE, The weight of direct aid in farm income

[4] Nicolas-Jean Bréhon, (2010) The CAP in search of legitimacy. Study available on the Robert Schuman Foundation website.

[5] Momagri, All European countries need regulatory mechanisms to support their agriculturehttp://www.momagri.org/FR/editos/Tous-les-pays-europeens-ont-besoin-de-mecanismes-de-regulation-pour-soutenir-leur-agriculture_703.html

[6] Jean-Pierre Butault, (2004) Support for agriculture: theory, history, measurement