Summary:

– The establishment of the Banking Union is essential to strengthen the eurozone by reducing fragmentation, breaking the vicious circle between sovereign and bank debt, and improving supervision.

– The Banking Union poses a reputational and arbitrage risk to the ECB, which has been entrusted with a dual mission.

– The provisions for resolution and deposit guarantee funds do not appear to be sufficient and risk undermining the credibility of the Banking Union’s ability to carry out its tasks.

In a first article by the same author published on the BSI Economics website, we presented the main components of the Banking Union. In this second article in this exclusive report on the Banking Union, we set out the reasons behind its creation, as well as the challenges and risks inherent in the implementation of its three components.

After many years of crisis, during which the eurozone revealed its fragmentation and fragility, it became necessary to strengthen European institutions in order to ensure greater banking and financial stability in the future. The Banking Union is there to strengthen Europe, and in particular the eurozone, and to prevent major financial turmoil in the future. However, as the Banking Union is the product of tough negotiations, the optimal solution has sometimes had to be sacrificed in favor of the lowest common denominator, which has led to several criticisms of its structure.

Why does Europe need the Banking Union?

There are five economic and structural advantages for the eurozone in implementing it.

1 – Completing the single currency and the eurozone banking market

The stability of the monetary system depends above all on confidence in the ability to convert banknotes into deposits and vice versa, and in the ability of banks to ensure the payment and transfer system. However, these beliefs are based on the ability of the authorities to intervene in the event of doubts about the viability of a bank in order to guarantee at least the continuity of the bank’s financial services. In addition, the creation of a minimum deposit guarantee in all European Union countries, as well as a provisioned fund, ensures that all euros in bank deposits (which represent 83% of M1[1]in the eurozone) have the same value, since all eurozone countries will be part of the Banking Union in order to prevent any country from having a « discounted » euro. This assurance was partially called into question by the Cypriot crisis in 2013 and will only become a reality once a European deposit guarantee fund is in place.

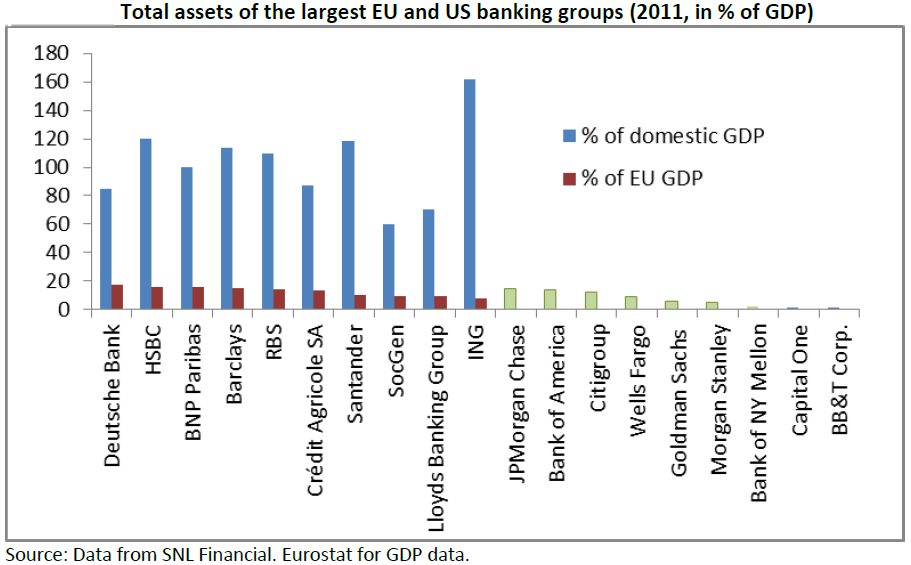

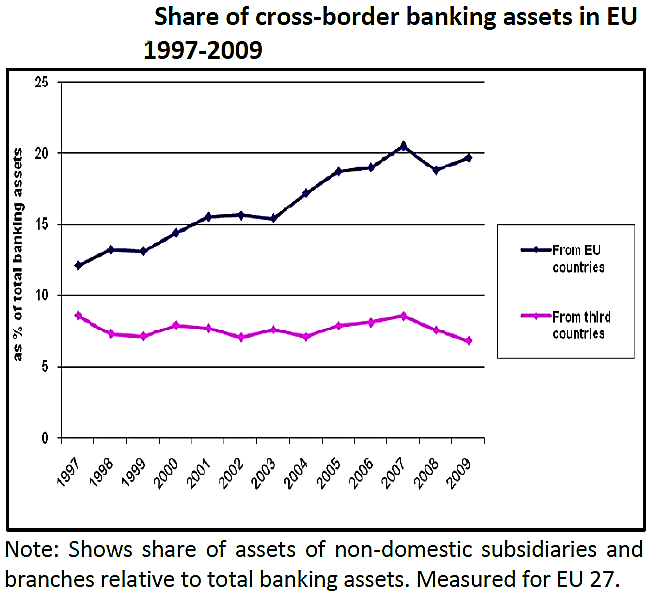

Between 1977 and 1993, the European Union established an integrated banking system. Two directives in particular (December 12, 1977[2], December 15, 1989[3]) organize the freedom of establishment and provision of banking services by introducing a single license. Any credit institution authorized by the competent authorities of a Member State may carry out banking operations throughout the European Union. European banks have since become largely transnational (see Figure 1). Whether due to their size (see Figure 2) or the complexity of their international operations, they have become too big and complex to be rescued by a single eurozone country. The Banking Union therefore remedies an unstable situation and completes the Europeanization of the banking market.

Graph 1

Source: Liikanen Report (2012)

Figure 2

Source: Liikanen Report (2012)

Finally, the Banking Union completes the European banking market by standardizing the application of European supervisory directives, in particular CRD IV (transposition of Basel III into European legislation). Before the SSM was established, each Member State had considerable leeway in implementing supervisory directives, which did not guarantee equal treatment and always left room for national bias. Agarwal et al (2012) showed that in the United States, federal regulators are less conciliatory than local ones.

2 – Combating the growing fragmentation of the eurozone

The subprime crisis and then the eurozone crisis revealed the fragmentation of the eurozone, which resulted in diverging interest rates (sovereign and bank loans) and unequal access to credit, particularly for SMEs. The rejection rate (loans refused out of total loan applications to banks) for SMEs in Spain and Italy rose from 10% to 16% between 2010 and 2013, while in Germany it fell from 6% to 2.5%. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 3, the interest rates paid by SMEs in Spain and Italy are double those paid in Germany.

Figure 3

Source: Al-Eyd and Berkmen, 2013, p. 9

Finally, fragmentation has been exacerbated by the return of domestic bias. National supervisors have encouraged banks under their supervision to reduce their exposure to risky countries, which has reinforced the transfer of capital to safe haven countries and ultimately led to a massive renationalization of bank-held debt. This fragmentation is a direct consequence of the fact that banks in countries in difficulty have become riskier due to their holdings of poor-quality assets (less favorable economic conditions increasing loan default rates and holdings of poor-quality national debt), which weakens these banks. At the same time, countries in difficulty have become less credible when intervention is needed. By establishing the SSM and the SRM, the Banking Union ensures the credibility of the rescue of a bank in difficulty by relieving states of this responsibility (see Chart 2), which will help to correct these divergences within the euro area.

3 – Breaking the vicious circle between sovereign and bank debt

The 2007 financial crisis caused the debt levels of eurozone countries to skyrocket, whether to finance stimulus plans, nationalize banks such as Northern Rock or Dexia, or provide loans and guarantees to the banking and insurance sectors. However, most of this newly issued debt was purchased by these same banks. For example, between November 2011 and April 2013, the amount of sovereign debt held by French banks increased by 30% to €282 billion, while the amount held by Italian banks increased by 60% to €404 billion. However, as we have just seen, a significant portion of the debt held by banks has been nationalized. As a result, any deterioration in a country’s situation, by increasing spreads, automatically[4]worsens the balance sheets of the banks that hold its debt. Conversely , any deterioration in a country’s banking sector may force the government to intervene to support it, further burdening its budgetary situation, and so on. Spain and Ireland have been particularly affected by this vicious circle, as in the case of the cajas[5]is emblematic, having had to be massively supported by the Spanish government. By breaking the link between governments and the country’s banking system, the banking union makes this type of scenario much less likely, thanks to the existence of safeguards with the SSM, resolution plans, and the SRF fund, which avoid government intervention.

4 – Internalizing the externality of national supervision in an international market

National supervisors have the sole task of preserving the stability of the national banking sector, without concern for the impact on the banking sectors of other countries. During the Irish banking crisis, the Irish government initially recapitalized its own troubled banks, such as Anglo-Irish Bank, on its own. This indirectly supported French, German, and British banks that had subsidiaries in Ireland and guaranteed numerous British deposits. Ireland therefore initially supported its banking sector alone, even though many other countries also had interests there.In Europe in particular, banks have become transnational (see Figure 1). Any decision taken by a national supervisor therefore has a significant impact on other countries in the euro area. The management of Dexia’s bankruptcy, for example, required coordination between France, Belgium, and Luxembourg. The Banking Union formalizes this cooperation and avoids any risk of negative externalities from a national supervisor.

5 – Reducing the risk of capture by the financial industry

The risk of capture, as described by Nobel Prize winner George Stigler, refers to a situation in which a public regulatory institution, although intended to act in the public interest, ends up serving private interests. Thus, the appointment of former bank employees to institutions responsible for supervising the banking sector may raise the question of the risk of capture. In the United States, for example, the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) was suspected of regulatory capture in the Madoff case.

In the context of the Banking Union, the concentration of supervisory powers, entrusting them to an institution with strong credibility and recognized expertise, and finally the establishment of a certain distance (especially geographical and political), reduces the risk of capture by the financial industry.

Outstanding issues

The Banking Union is an undeniable step forward, but as it is the result of multiple negotiations and compromises, many challenges remain unresolved and could hinder its smooth functioning.

1 – A questionable structure

While the decision to entrust supervision to the ECB is justified by the fact that it already holds extensive information on the health of banks as part of its mission to ensure the stability of the monetary system and by its well-established reputation, there is a risk that its reputation could be called into question in the event of the failure of banks under its supervision. If a central bank’s reputation deteriorates, its ability to guide the financial markets is called into question. This is what happened to the Bank of England (BoE) in 1990, leading the government to withdraw its banking supervision mandate in 1997 and entrust it to the Financial Services Authority (FSA).

In addition to this reputational risk, there is also a risk of arbitrage between monetary policy and the supervisory function. For example, in the event of inflation coupled with a banking crisis, the ECB would have to raise its key interest rate on the one hand and lower it on the other. However, the prevailing view seems to be that the supervisory role must take the key interest rate as a given and use other instruments to fulfill its mission.

There is also the question of the resources available for the supervisory mission. The ECB is self-financing, but its new supervisory mission requires a substantial budget. The Banking Union will only be credible if adequate resources, both financial and human, are put in place. The SSM budget is expected to be separate from the budget for monetary policy. The SSM budget will be funded by annual fees paid by the banks under the SSM’s responsibility. With regard to human resources, the SSM and the SRM are currently drawing on many executives from national supervisory authorities, ensuring experienced staff but weakening national regulators in the short term.

The decision to focus on the largest banks in the eurozone (around 130 directly supervised by the SSM) is questionable, as banks such as the Spanish cajas, which were severely affected by the property bubble, and the German Landesbanks, which were heavily involved in securitization, can also be a source of financial crisis. While the ECB can decide to take charge of any bank, not supervising them directly means potentially failing to see an increase in risks.

2 – Inadequate levels of provisioning

The MRU fund, representing 1% of covered deposits, is expected to reach €55 billion in 2024. Its calculation method is based on the amount of deposits, so retail banks will be the major contributors, unlike those that finance themselves on the markets. This calculation method risks encouraging the use of more volatile market liquidity and securitization, techniques that allow banks to finance themselves with a minimum of deposits and therefore contribute less to the MRU fund. However, these practices run counter to the objective of a stable banking market.

If we compare the amount set aside for the MRU fund with the sums advanced by governments since 2007, the size of the fund appears insufficient in the event of the failure of a major bank. For France, the amount of public aid and guarantees provided during the financial crisis is estimated at €413 billion (Alpha Value, 2013): €320 billion in refinancing guarantees (via the Société de Financement de l’Économie Française), €40 billion in temporary recapitalizations, and €53 billion for the French part of Dexia (approximately €6 billion in recapitalization and €47 billion in refinancing guarantees). For Germany, the figure is €480 billion, for Ireland €400 billion, for the United Kingdom €363 billion, for the Netherlands €220 billion, and for Spain €130 billion. And while the ESM fund is authorized to borrow if necessary, a major crisis that depletes its reserves could also prevent it from raising sufficient funds.

However, the ESM fund is not the only means of action. The Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) already used during the crisis to rescue Irish banks could coexist with the ESM fund but continue to play the role of PDR and only help banks in liquidity crisis. The most likely scenario is that ELA will be replaced by the ESM fund. The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) will also be able to recapitalize banks directly. An agreement in principle was reached in early May 2014 that should allow the ESM to recapitalize banks under the same conditions as the MRU. However, while the ESM’s funds are much larger (€700 billion) and increase the MRU’s credibility in its ability to deal with a serious crisis, it should be remembered that the ESM’s primary objective is to support states, not banks, and that the conditions for using ESM funds require participating states to agree, which is not consistent with the need for rapid action in the event of a bank’s risk of bankruptcy. The question of the consistency of the MRU fund also arises, as the latter does not have the means to carry out its mission (having to call on another fund in the event of a serious crisis), its credibility is uncertain.

The future deposit guarantee fund will only cover 0.8% of deposits, which may be insufficient in the event of a major bankruptcy or even a run on several banks. These inadequate funding levels are currently the main criticism of the Banking Union and its main weakness, to the point where they could undermine its credibility.

3 – The problem of sequentiality

The Banking Union is a whole, with the three pillars complementing each other. However, it was not possible to implement them all at the same time, so a sequence had to be established to facilitate negotiations, at the risk of weakening the Banking Union during the transition phase.

The implementation of the SSM without the SRM until 2015 means that the ECB will communicate on the situation of banks without having any means of action, which may aggravate the situation of these banks, mainly in the small countries of the eurozone (Slovenia, Cyprus). The implementation of a stress test and the AQR will effectively enable the ECB to assess the situation of the banking system, but if the results indicate that a bank is not sufficiently capitalized, the MSU will have no means of action and will have to resort to emergency programs such as the ESM if necessary, which will not send a good signal about the current management capacity of the banking system and the desire for normalization. However, even the use of the ESM requires the consent of the 17 eurozone countries, which runs counter to the very purpose of the MRU.

The MRU fund will be built up over eight years and its mutualization remains threatened by states with veto rights, which will prolong this uncertainty over a long period.

No agreement has yet been negotiated on the deposit guarantee fund. Worse still, many states expressed their disapproval of the establishment of a deposit guarantee fund during the negotiations on the MRU. However, an incomplete banking union will never be able to achieve its objectives.

4 – Risks of coordination problems with national authorities and agencies

Several European agencies have been set up in recent years to promote cooperation between national agencies, such as the European Banking Authority and the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB). However, despite the risk of duplication with the Banking Union, their abolition is not on the agenda. The risk of duplication with the ESRB is clear and threatens to cause cooperation problems. With regard to the EBA, although a compromise has been reached that gives the EBA the role of regulator, with the aim, for example, of standardizing the application of prudential rules, and the ECB the role of supervisor, the separation of tasks is not as clear-cut in practice. Although the task of conducting stress tests has been taken away from the EBA and entrusted to the ECB, the EBA conducts the AQR and participates in the implementation of the stress test with the ECB.

Finally, it remains to be seen how coordination between national supervisors and the ECB will work . While the EBA will be responsible for settling any disputes between the ECB and national regulators, the question arises as to day-to-day coordination, for example with regard to data transmission.Member States retain a certain amount of influence within the Banking Union, particularly during the ramp-up phase, which may limit its capacity for action. For example, they have a right of veto over the mutualization of the MRU fund and remain involved in the resolution process (in the resolution board), which may prolong the process through negotiations.

Conclusion

The establishment of the Banking Union is essential for the eurozone to meet its current and future challenges, but it remains incomplete and unstable until the three pillars are fully in place.

Notes:

[1] M1 is the first aggregate; these aggregates range from the narrowest to the broadest, from M1 (an aggregate comprising only the most immediately available amounts, such as sums deposited in current accounts) to M3.

[2] The 1977 directive removes most of the obstacles to the freedom of establishment of banks and other credit institutions; establishes common principles for the granting of banking licenses; and introduces the basic principle of home country control.

[3] The 1989 directive removes the remaining barriers: it confirms the principle of a single license allowing banks and other credit institutions to offer their services throughout the Community, either through branches or directly; national supervisory authorities must mutually recognize authorizations issued by other Member States; a list of banking activities is established; a minimum capital requirement of ECU 5 million is required to establish a bank; supervisory rules are set out concerning, among other things, internal management and auditing of accounts.

[4] Inverse relationship between the rate of a bond and its value.

[5] Spanish regional banks heavily involved in real estate and infrastructure financing.

References:

Agarwal, Sumit, David Lucca, Amit Seru, and Francesco Trebbi, (2012), « Inconsistent Regulators:

Evidence from Banking, » National Bureau of Economic Research, No. 17736, January.

ECB, (2014), « Progress in the operational implementation of the Single Supervisory Mechanism Regulation, » SSM Quarterly Report 2014/2

Jézabel Couppey-Soubeyran, (2013), Interview, “The Banking Union, an incomplete project , » BSI Economics

Christian de Boissieu, (2014), “Towards a Banking Union: Open Issues”, report of Conference co-organized by the College of Europe and the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre in Bruges in April 2013

Duncan Lindo, Katarzyna Hanula-Bobbitt, (2013), « Europe’s banking trilemma, » Finance Watch

Guillaume Arnould, (2014), » The Banking Union, a fundamental but unfinished project (1/2) , » BSI Economics.

Jeffery Gordon, Georg Ringe, (2014), » How to save bank resolution in the European banking union, » Vox

MEMO/13/1176, European Commission (2013)

MEMO/14/295, European Commission (2014)

Morgane Delle Donne, (2013), » Banking union: will the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) replace Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) in the management of banking liquidity crises? , » BSI Economics

Patrick Artus, Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, Laurence Boone, Jacques Cailloux, and Guntram Wolff, (2013), » A Three-Step Path to Reunifying the Euro Area, » CAE Working Paper

Rishi Goyal, Petya Koeva Brooks, Mahmood Pradhan, et al., (2013), « A Banking Union for the Euro Area, » IMF Staff Discussion Note February 2013 SDN/13/01

Thorsten Beck, (2013), « Banking union for Europe – where do we stand? », Vox

Victor Lequillerier, (2013) , » And then the Single Supervisory Mechanism arrived… , » BSI Economics

Zsolt Darvas and Silvia Merler, (2013), “The European Central Bank In The Age Of Banking Union”, Bruegel Policy Contribution Issue 2013/13 October 2013