Summary:

– TARGET2 is the money transfer system that connects financial institutions in the eurozone.

– TARGET2 balances are the positions of national central banks vis-à-vis the Eurosystem.

– Changes in these balances reflect the financial disintegration of the eurozone and the precarious external position of some of its members.

– In the short term, they are an effective barometer for monitoring the evolution of the monetary crisis affecting the eurozone.

The evolution of TARGET2 balances has been the subject of much commentary by economists and the specialized press for several months. Their analysis is the subject of much debate, although everyone agrees that they reflect serious internal imbalances within the eurozone. In this article, we will attempt to understand why TARGET2 balances have become such a controversial issue in understanding the eurozone crisis, and to make sense of their amounts, which are now considerable in central bank balance sheets.

What is TARGET2?

TARGET is the acronym for the Trans-European Automated Real-time Gross settlement Express Transfer system. This system was created to provide platforms for the secure and rapid exchange of very large amounts of money within the eurozone, with the aim of promoting the emergence of a harmonized and reliable money market. When TARGET was introduced, the system consisted of the large-value payment platforms of all European Union member countries. The gradual migration to the TARGET2 system was completed on May 19, 2008, for all members of the eurozone and Denmark (joined by Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania); it now allows monetary and financial institutions in these countries to be directly connected to the SWIFT interbank network. Each bank account has a SWIFT code (or BIC code), which can be found on your bank statement. The TARGET2 system is also responsible for managing the ECB’s monetary policy operations and the transfers they generate between the NCBs of the Eurosystem: open market operations and refinancing operations.

Source: BS Initiative

Let’s imagine that a German agricultural equipment manufacturer (banked at Deutsche Bank) and a Spanish farming corporation (banked at Banco Santander) do business and sign a contract worth €1 billion. In exchange for the delivery of machinery, the farmers will have to pay this amount to the German company.

To do this, Banco Santander borrows from the Spanish central bank (BoS), which transfers the amount to be paid to the German central bank (Bundesbank) via the ECB, which credits Deutsche Bank. The process that enabled the German manufacturer to recover the amount of its sale therefore had an impact on the balance sheets of several players: Deutsche Bank now has a claim on the Bundesbank, which has a claim on the ECB, which has a claim on the BoS, which has a claim on Banco Santander.

TARGET2 balances

The eurozone consists of a group of 17 countries that have economic and financial relations with each other, giving rise to flows of goods, services, financial products, currency, etc., which are quantified in their balance of payments.

On one side of this balance of payments is the current account, the balance of which gives rise to a country’s financing needs/capacity.

On the other side is the financial account, which shows the flow of financing received by the country. This flow may exceed or be less than the current account balance.

In a « traditional » exchange, i.e., between two countries with two different currencies, this difference gives rise to an adjustment through movements in the foreign exchange reserves of the central banks of the two countries on the one hand, and/or through the creation of money on the other. The financial account is thus balanced with the current account.

In the euro area, the adjustment takes place differently, insofar as the central banks of the countries trading with each other have authority over the same currency. A euro area country whose current account is not balanced therefore causes a net outflow of central bank money to the economies of its monetary partners. In this case, we do not refer to reserves but to TARGET balances, which is the name of thetrans-European automatedreal-time gross settlement express transfer system, in operation since 1999 (since 2008 in its current form: TARGET2).

TARGET2 balances therefore correspond to intra-euro area foreign exchange positions (although there may be some nuances in their amounts), which correspond to the positions of NCBs vis-à-vis the Eurosystem.

It should be noted that TARGET2 balances are stocks, not flows, and that they constitute a zero-sum game between the NCBs of the euro area.

Furthermore, some countries use the TARGET architecture but do not have the euro as their official currency; in this case, we do not refer to TARGET2 balances.

TARGET2 balances (EUR, billions)

Sources: University of Osnabruck, NCBs, BS Initiative

Impact on central bank balance sheets

Central bank money in circulation is recorded as a liability on the balance sheets of the national central banks of the euro area. However, although each central bank in the euro area has its own balance sheet, this part of the liabilities payable by the national central banks of the euro area corresponds to an asset that is perfectly fungible and common to all of them: the euro currency. Thus, the Bundesbank has on the liabilities side of its balance sheet the amount of euro currency that it has issued into circulation. However, Germans now hold more central bank money than the Bundesbank has issued. Why? Because part of the issues of other national central banks in the euro area has ended up in the German economy (we will see how below).

To simplify the process, we can say that, for example, the Spanish central bank has issued euros that have entered the German economy, making the Bundesbank accountable to its residents for this currency. In the traditional game between two central banks, each managing their own currency, the adjustment is made through changes in reserves or money creation. In the eurozone, the use of a common unit of account for payments to all members gives rise to an item called « other claims » in central bank balance sheets. This corresponds to central bank claims on other central banks. A kind of foreign exchange reserves in its own currency. In our example, the Bundesbank becomes a debtor of the additional euros in its economy vis-à-vis domestic agents; in return, it indirectly (via the ECB) has a claim on the Spanish Central Bank.

There is debate about the risks incurred by countries with significantly positive TARGET2 positions (notably Germany and the Netherlands). Since TARGET2 claims are positions vis-à-vis the Eurosystem, the default of a Eurosystem central bank with a TARGET2 debt would have consequences shared among all euro area members, depending on their share in the ECB’s capital.

|

Limitations on the interpretation of TARGET2 balances TARGET2 balances present some difficulties of interpretation. The LTRO and VLTRO refinancing operations implemented by the ECB have had an amplifying effect on the evolution of TARGET2 balances. As second-tier banks have the possibility of refinancing themselves via their subsidiaries with the NCB of another member country, they have been able to withdraw liquidity after refinancing. The phenomenon of capital flight may therefore be overestimated. In addition, the operations of certain banks located outside the euro area require the intervention of banks with TARGET2 accounts. Finally, some international payments by euro area banks are not settled via TARGET2. |

The origins of TARGET2 balance divergences

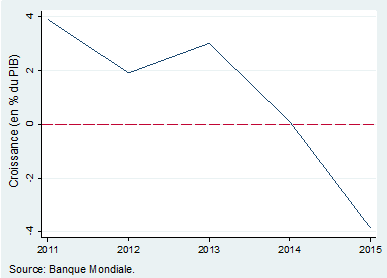

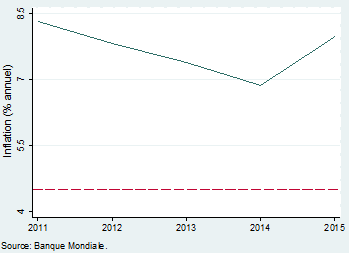

The introduction of the single currency boosted trade between eurozone countries. From 2002 to 2008, the weight of foreign trade increased significantly (+45% to €4.35 trillion over this period), within an institutional framework similar to a fixed exchange rate system. By promoting intra-zone trade, EMU created shocks in the trade balances of member countries, some positive (particularly for Germany) and some negative (Greece, Spain, Portugal), which led to the emergence of lasting current account imbalances and the accumulation of significant external debt. The characteristics of the financing of these external debts are directly responsible for the monetary imbalances affecting the euro area, as they have made certain countries dependent on financing flows from international creditors who, in times of crisis, have withdrawn their capital.

Until the onset of the crisis, the TARGET2 balances of the NCBs were relatively close to equilibrium. Since the crisis began in 2007, TARGET2 balances have become significant items on central bank balance sheets. The liquidity crisis that affected trade between banks in « risky » countries and banks in other countries is at the root of this increase. In fact, economic agents (particularly banks) financed each other without regard to national considerations. The decline in their foreign exposures led to the partial intermediation of transnational financing through TARGET2 balances. While this did not cause currency crises in countries that experienced capital outflows, it did increase the liabilities of their NCBs.

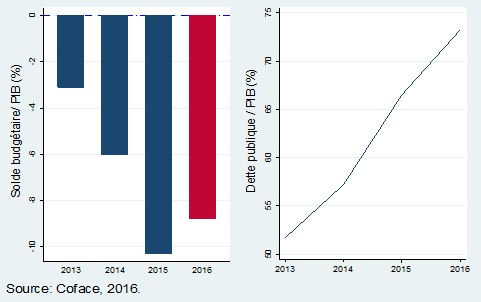

To better understand this phenomenon, let us take the example of Spain, which is the eurozone country with the highest external debt (€976 billion at the end of 2012, BoS figures) in the eurozone and whose central bank has the largest TARGET2 debt. We can see that its external debt in the « other investments » and « portfolio investments » categories has fallen sharply in recent quarters. This does not mean that Spain is reducing its external debt, but that its debt is being financed differently. Non-resident agents no longer wish to invest their money in this economy in the form of deposits, interbank loans, purchase credits or financial assets.

Spain’s external position (EUR, billions)

Sources: Bank of Spain, BS Initiative

This phenomenon, which corresponds to massive capital outflows, has been at work in several eurozone countries (Italy, Spain, Greece, Ireland, Portugal). It has had two consequences: the expansion of positions between national central banks and the financial disintegration of the eurozone (which has prevented the financing of peripheral economies).

This financial disintegration is the cause of the increase in TARGET2 balances. In countries that are viewed with mistrust by investors, TARGET2 balances have fallen and it is the positions of their national central banks that bear the unfunded portion of external debt. In countries that benefit from capital repatriation, particularly Germany and the Netherlands, the opposite phenomenon occurs. Their investments in their European partners are declining, while current account balances remain substantial, generating net capital inflows that inflate their NCBs’ TARGET2 claims. These flows explain the low amounts of refinancing operations carried out in certain countries (notably Germany).

To prevent the effects of this capital flight in peripheral countries, the monetary authorities have carried out massive refinancing operations (massive MROs followed by LTROs) to meet liquidity needs and limit the credit crunch. The creation of stability funds (MESF, EFSF, and ESM) is a major response to the short-term liquidity problem faced by governments and banks, while the Banking Union project would lay the foundations for the sustainable financial reintegration of the eurozone.

Sources: ECB, BS Initiative

|

Bank run in the eurozone? The press has often mentioned a bank run phenomenon that is said to be underway in the eurozone. A bank run manifests itself in savers’ mistrust of banks, prompting them to withdraw the balance of their deposit accounts in cash. In the eurozone, this can take the form of a transfer from a euro account to an account with a safer bank or country (a bank that will not go bankrupt, a country that will not leave the eurozone). We said earlier for Spain (and this is true for other peripheral countries) that the « other investments » item in their external position had deteriorated rapidly. If we look at the composition of this item (deposits, interbank loans, purchase credits), we see that bank deposits have declined slightly or stagnated in countries in difficulty (except Greece, where deposits are in sharp decline), in amounts that are not comparable to TARGET2 balances. Except in Greece, there is therefore no bank run in Europe. The key factor in understanding the evolution of TARGET2 balances is the interbank market and the external position of banking agents, which shows financial and banking disintegration in the eurozone. |

Should TARGET2 imbalances raise fears of a breakup of the eurozone?

To answer this question, it would be interesting to compare the phenomenon observed since 2008 in the eurozone (increase in positions between central banks). The search for a similar system of independent central banks that have their own balance sheets but share a common currency on their liabilities leads us directly to the United States (ISA system).

Source: Bruegel

If we look at the « ISA balances » in the United States, we see that 2008 was also a year of shocks. This reveals something very important: the emergence of TARGET2 balances does not necessarily foreshadow a risk of a breakup of the eurozone. In fact, in the United States, the emergence of these imbalances provokes much less emotion and the risk of monetary secession is highly unlikely.

However, it should be noted that the United States has a considerable advantage over the eurozone in terms of financial integration. On the one hand, the federal budget is large, unlike in the eurozone (which does not have its own budget, since the common budget of the member states is that of the European Union). On the other hand, there is a strong American identity, whereas European countries are currently hesitant about their common future.

Conclusion

TARGET2 balances are therefore the financial manifestation of imbalances in the balance of payments of eurozone countries. Their evolution has shown how fragile the financial position of some countries was. Capital flight and the credit crunch in peripheral countries have forced the ECB to take large-scale action, which is now beginning to bear fruit. In recent months, we have seen the beginning of a rebalancing of TARGET2 balances.

The renewed confidence in peripheral countries, which is already reflected in a recovery in portfolio investment, the firm stance of political leaders on the irrevocable nature of the single currency, and the easing of tensions in the interbank market will allow this rebalancing to continue.

While TARGET2 balances are an effective barometer of financial and banking stability and harmony in the euro area, they are not a measure of the risk incurred by NCBs (both creditors and debtors). Ensuring the health of the eurozone member economies requires, above all, a rebalancing of relations between its members in order to create a coherent economic area and avoid the domestic retreats that caused the European monetary crisis.

References

– Banque de France, « Target 2 balances »

– Michiel Bijlsma and Jasper Lukkezen, « Target 2 of the ECB vs. Interdistrict Settlement Account of the Federal Reserve »

– Patrick Artus, « Is the Bundesbank’s Target 2 balance exposing Germany to additional risks? »

– Patrick MC GUIRE, Stephen CECHETTI and Robert MC CAULEY, « Interpreting TARGET2 balances »

– Patrick HARAN and Samuel BAILEY, « Analysis of Recent Monetary Operations & TARGET2 Developments »

– Karl Whelan, « Target2 and the Euro Crisis »

– Stefan HOMBURG « Notes on the TARGET2 dispute »