Summary:

– In recent years, Spain has implemented a policy of competitive devaluation while simultaneously reducing private sector debt and making its labor market more flexible.

– The adjustment of unit labor costs, combined with an increase in private companies’ profit margins and a decline in producer prices, has enabled Spain to emerge from economic recession thanks to foreign trade, reflecting a return to price competitiveness.

– However, private sector deleveraging and all the economic reforms implemented have not had the expected effects on the recovery of employment and investment, and it would even appear that Spain is paying the price for its regained price competitiveness.

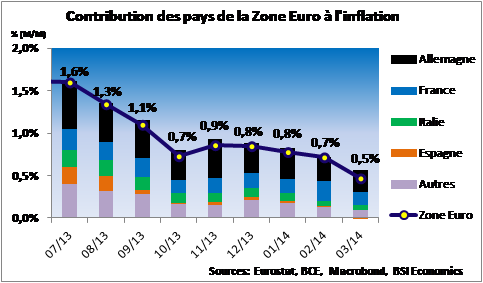

– Disinflation has contributed to lower consumer prices, which may make the economy more attractive internationally, but deflationary risks persist and could threaten the recovery despite clear improvements in early 2014.

Hailed as the miracle cure for reviving economic activity, price competitiveness is the battle cry of many eurozone countries, particularly those on the periphery: Ireland, Portugal, and Greece. This quest for price competitiveness has led several countries to implement far-reaching reforms to stimulate economic activity through exports. Spain is one of the countries within the Eurozone that has so far benefited most from its reforms to increase price competitiveness. By the end of 2013, the country was emerging from recession, and the growth outlook for 2014 points to the start of an economic recovery (with GDP growth of +0.8% forecast for 2014, according to Consensus Forecast).

Improving price competitiveness is a key step for Spain, and this model seems to be bearing fruit, given the positive trade balance figures and, more specifically, exports. However, given the current difficulties (persistently high unemployment and low investment), some doubts may be raised about the real advantages of this model, based on competitiveness, particularly in the medium term.

Emerging from the crisis through private debt reduction and wage moderation

Between 2000 and 2008, Spain experienced a period of average annual growth of 7.1%, compared with an average of 4.2% in the eurozone. However, during those years, it was accumulating ever-increasing private debt, which gradually led it into a deep recession (average growth of -1.2% since 2009): real estate crisis, increase in the number of business failures, severe instability in the banking system, public finance slippage, and sovereign debt crisis.

Even as the country embarked on a course of economic austerity and implemented structural reforms, Spanish companies entered a cycle of private deleveraging: between 2010 and 2013, private debt fell from 229% of GDP to 209%, compared with an average of 100% in the eurozone.

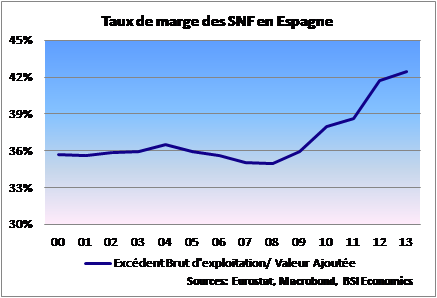

In a previous article published on BSI Economics, the mechanism of private deleveraging in Spain was examined: companies managed to reduce their gross payroll, notably by cutting the number of employees. They were then able to maintain their profit margins by distributing added value in a way that favored profits over payroll.

Between 2007 and 2013, while value added (VA) growth fell by 4 percentage points, employee compensation growth fell by 17%, while gross operating surplus (GOS), which can be equated with corporate profits, increased by 13%. This allowed companies to increase their profit margins (EBIT/VA), opening up several possibilities: paying off debts and lowering consumer prices to become more attractive internationally.

A success in terms of increased price competitiveness…

Regaining price competitiveness is no easy task, even for a country like Spain, the fourth largest economy in the eurozone, which has a developed and innovative industrial base (in sectors such as pharmaceuticals and telecommunications, for example). The implementation of structural reforms was almost inevitable given the deterioration of Spain’s price competitiveness in the 2000s. The transition was quite long before positive results were seen. Spain relied both on the deleveraging of private companies and on wide-ranging reforms to make its labor market more flexible: new employment contracts with trial periods, reduction in employer contributions, lower dismissal costs, stricter conditions for accessing unemployment benefits, and more flexible collective bargaining.

Membership of the eurozone does not allow countries seeking to boost their competitiveness to devalue their exchange rates. Given the structural imbalances in several countries in the zone, including Spain, a fall in the exchange rate (and therefore in the euro) would have proved insufficient to make them more attractive. These countries therefore implemented competitive devaluation policies, based on production costs. The fall in unit labor costs[1](ULC) therefore appeared to be a decisive step towards greater competitiveness. Between early 2009 and 2014, Spanish ULCs fell by 6% (compared with an average decline of 8% in peripheral countries but a 5% increase in the eurozone).

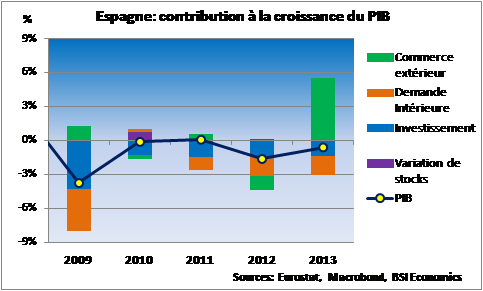

The increase in private sector margins associated with this decline in labor costs has therefore enabled Spanish companies to lower their consumer prices. By the third quarter of 2013, Spain was finally able to reap the benefits of its efforts to emerge from recession, thanks in particular to a positive trade balance (a greater increase in exports than in imports), which helped to drive growth. Exports, which accounted for 24% of GDP in 2009, now stand at around 34%, compared with 32% for imports, which is in line with the level at the beginning of the 2000s. This marked improvement in foreign trade is a clear sign of Spain’s success in making itself more attractive.

… But this does not mask certain concerns: weak domestic demand and unemployment

External demand is driving Spanish growth, and this situation is expected to continue in 2014. However, many problems remain: despite a small recovery in the first quarter of 2014, investment (both public and private) is too low, the unemployment rate remains above 25% of the working population, domestic demand remains sluggish, and deflationary risks persist.

Private deleveraging has led Spanish companies to increase their profit margins in order to reduce their financial debt. They have therefore accumulated significant savings (a 40% increase in corporate savings between 2009 and 2013), which they are using to repay their debts and self-finance. The difficulties faced by Spanish banks and the already high level of corporate debt have contributed to a liquidity crunch in the economy. Unable to access credit, companies have relied heavily on their savings for self-financing. The self-financing ratio (savings/gross fixed capital formation) quickly exceeded 100% to reach 135% in 2013, strongly reminiscent of the situation of Japanese companies in the 1990s, which were mired in deflation.

The financing rate (gross fixed capital formation/VA) fell sharply: in 2007 it was 37% and has been stagnating at around 24% for the past four years. Investment contributed negatively to GDP growth in 2013 and appears to be recovering in 2014, but it will remain weak until the credit channel is reactivated.

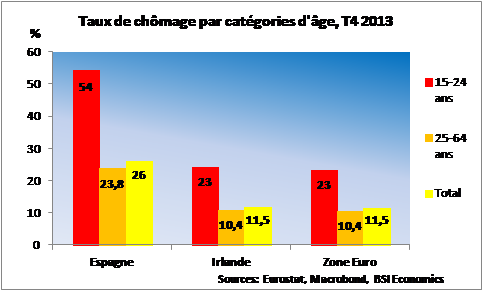

Private investment is not the only source of concern in Spain, given the persistent problems of unemployment. Labor market flexibility has certainly improved the competitiveness of businesses, but the recovery in employment has been slow to materialize, even though the unemployment rate remains very high (25.6% in March 2014). Compared with Ireland, another peripheral country that also experienced a real estate crisis and is in the midst of a private deleveraging cycle, unemployment figures in Spain are significantly higher and therefore worrying.

Young people are particularly affected by unemployment, mainly because of their lack of qualifications. A 2012 OECD study showed that around 70% of young people aged between 15 and 29 in 2010 did not have the equivalent of a high school diploma or had never been in employment. Many young people worked in construction in the 2000s, and following the real estate crisis, many found themselves unemployed, without sufficient qualifications to quickly find another job in a difficult economic climate.

Labor market reforms should help to reintegrate the unemployed. However, the current flexibility of this market, particularly through the ease of hiring temporary workers, does not necessarily guarantee job stability and generally results in a form of precariousness. Overall, gross disposable income (GDI) has fallen by 3.2% over the past five years. This decline in GDI has a direct impact on domestic demand, which is very weak and contributed negatively to GDP growth in 2013.

Persistent disinflation = small advantage and big danger

Domestic demand is certainly sluggish, but it could benefit from lower inflation and falling prices. Indeed, the harmonized index of consumer prices (HICP) continues to fall. Despite wage moderation, falling prices could stimulate private consumption in 2014, as in the last quarter of 2013, when it rose by 0.5% compared with the previous quarter. Despite this windfall effect, the risk of deflationcannot be ruled out in Spain.

Efforts by companies to reduce debt and lower consumer prices, high unemployment, and insufficient investment are contributing to this decline in the HICP, but this disinflation should not turn into deflation, which would ultimately jeopardize the recovery in Spain. To kick-start inflation, commercial banks will need to supply the economy with credit. Spanish banks have now largely shed the sovereign debt risk that weighed on their balance sheets (the yield on 10-year Spanish bonds fell from 7.6% in July 2012 to 3.06% at the end of April 2014) and the likely, or at least expected, next LTRO operation by the European Central Bank (ECB) should enable them to restart the credit machine.

The latest ECBbank lending surveys have been optimistic about credit supply conditions, with low interest rates. However, the real economy does not seem to be benefiting from these favorable conditions, mainly due to weak demand for credit. Companies and households, which are in the midst of a deleveraging phase, remain reluctant to take out new loans. Even though borrowing rates are low, collateral requirements remain too high. To remedy this, the Spanish government recently proposed alternative sources of financing for SMEs in order to circumvent these bank requirements. However, without a recovery in credit, Spain risks entering a deflationary spiral.

Although Spain is not in the same situation as Japan in the 1990s, there are certain similarities that could give rise to doubts. If the country does not quickly find solutions to stimulate private consumption, domestic demand will remain largely insufficient to support growth. Weak domestic demand, coupled with high and persistent unemployment, would then fuel a negative spiral: contraction in demand, falling prices, rising debt burden (the debt-to-GDP ratio increases automatically as prices fall), bankruptcies and corporate defaults, contraction in demand, etc.

Conclusion

The Spanish economy is very likely to continue its recovery in 2014, supported by foreign trade. This upturn is largely due to the renewed attractiveness of the Spanish economy. This increase in competitiveness is the result of a long adjustment process, based on numerous reforms, some of which have been painful.

However, this competitiveness masks many problems. Labor market flexibility is certainly an asset, but unemployment is still too high and is likely to lead to significant job insecurity. The risks of such a situation could be, at best, weak domestic demand for years to come or, at worst, the emergence of deflationary pressures.

An economic model based on competitiveness is undeniably a major asset for emerging from the crisis and reviving activity. But an economy cannot rely solely on this characteristic in the long term if it wants to achieve solid and sustainable growth.

Notes:

[1] According to the INSEE definition, « Unit labor costs are labor costs per unit of value added produced. Labor costs include salariesand gross salaries paid by the employer (remuneration, bonuses, paid leave, commissions, and fees, including social security contributions), plus employer contributions. »

References:

– BSI Economics, (2013), » Corporate debt reduction: what does the future hold? , » Lequillerier Victor.

– BSI Economics, (2014), » What if the euro wasn’t the problem , » Lorre Geoffrey.

– BSI Economics, (2013), » Competitiveness, a concept to be used with caution , » Pietrzyk Nicolas.

– Consensus Forecast, (2014), Euro Area, Focus Economics, March 2014.

– IMF, (2013), 2013 ARTICLE IV CONSULTATION SPAIN, August 2013.

– OECD, (2012), Economic Survey: Spain, November 2012.