Summary:

– Securitization refers to the process that underpins, in particular, the creation of « risk-free » securities from risky assets

– Securitization took off in the early 1980s in the context of the USsavings and loan crisis

– Poor assessment and understanding of credit risk explain the enthusiasm for these securities until the financial crisis

– The EU’s capital markets union project is bringing « simple, transparent, and standardized » securitization back into favor, seeing it as a tool to stimulate investment by strengthening its link with savings

In 2004, Business Week magazine named him « one of the greatest inventors of the last 75 years. » In 2009, he was one of the « 25 culprits of the financial crisis »according to Time magazine. His name: Lewis Ranieri, former trader and vice president of Salomon Brothers, the first to use the word « securitization » (1977), one of the modi operandi of structured finance, which experienced a meteoric rise from the 1980s onwards and a collapse in 2007-2008.

However, securitization is now back in the spotlight, as evidenced by the priority it represents in the short term in the capital markets union projectlaunched by the Juncker Commission in January.

After a decline as spectacular as its rise, is securitization rising from the ashes in a new form?

1 – Securitization, a financial innovation…

Securitization is a financial technique that involves grouping together a number of assets, such as mortgages or bonds (underlying assets), and issuing debt securities backed by these assets. These securities are ranked in the form of « tranches » that determine their priority for repayment in the event of default on the underlying assets. This hierarchy makes it possible to issue securities with a risk that is significantly lower or significantly higher than the average risk of the underlying assets. It was this technique that made it possible to create AAA-rated securities from mortgages granted to insolvent American households, which was at the root of the subprime crisis.

Let’s imagine that we group together two identical bonds with a 10% probability of default, which pay 1 or 0 and whose defaults are not correlated. Let’s imagine that from this portfolio of two bonds, we issue two tranches, each paying 1 or 0, a « junior » tranche and a « senior » tranche, and that we define the « junior » tranche as the one that suffers the first loss of 1. The « junior » tranche therefore pays 0 if one of the two bonds defaults and 1 otherwise. The « senior » tranche pays 0 only if both bonds default and 1 otherwise. A simple calculation[1] shows that, under these assumptions, the probability of default of the « junior » tranche is 19% (significantly more than the 10% of the underlying bonds) and that of the « senior » tranche is only 1% (significantly less). Thus, the two initial bonds have been « structured, » i.e., refinanced, to create a bond that is riskier than they are and a bond that is significantly less risky. This process is called « securitization. »

The tranches described in the example above are CDOs.[2]. By repeating the process and combining the « junior » tranches, a CDO squared (CDO of CDOs) would be created. In Europe, the most numerous issues since 1999 have been RMBS[3][3] (54%). There are many acronyms describing the type of underlying assets, which can vary but must generate future payments. For example, securitizing 10 years of royalties on 25 albums allowed David Bowie to receive $55 million in one lump sum without having to wait 10 years!

Securitization makes it possible to create securities with differentiated risk across tranches, which benefit from diversification of the risk of the underlying assets, and for the issuer to benefit from immediate payment of expected future cash flows.

2 – … which exploded in the 1980s, a trend that was interrupted by the financial crisis of 2007-2008…

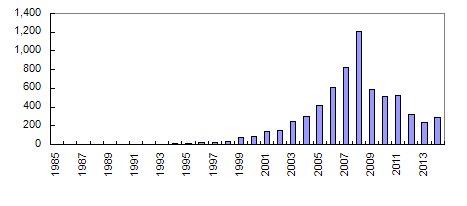

Figure 1: Issuance of securitization vehicles in Europe (USD billions)

The take-off of securitization can be traced back to the US savings and loan crisis of the 1980s.

Faced with spiraling inflation in the context of the oil crisis, the Fed, then led by Paul Volcker, decided in October 1979 to implement a sudden monetary tightening. The Fed funds rate[4] rose from 10% to 18% in just a few months. However,savings banks were then financing real estate loans mainly at fixed rates with short-term deposits. Typically, a savings bank could find itself paying an interest rate of around 15% on deposits financing (old) real estate loans granted at a rate of 5%[5]. In order to relieve thesavings banks, in September 1980 the US Congress passed a tax break allowing banks to recover from the tax authorities the loss associated with the sale of loans, i.e., the difference between their book value and their market value, which was significantly lower (due to the impact of the rise in interest rates on mainly fixed-rate loans). This measure triggered a massive sale of mortgage loan portfolios bysavings banks. For a savings bank, this meant selling its loans and buying those of others in order to benefit from the tax relief. A bank, Salomon Brothers, and one of its employees in particular, Lewis Ranieri, found themselves in the middle of these transactions. Initially, the bank bought and sold real estate loans. The next step was to securitize them.

However, there were two obstacles to overcome before the securitization of such loans could attract a broad base of investors, including U.S. pension funds.

First, many of these loans were not eligible for a guarantee from Ginnie Mae, a mortgage guarantee company owned by the US government. This meant that the corresponding bonds could not rely on the creditworthiness of the US government. After lobbying efforts, particularly by Salomon Brothers, this was achieved in 1981 with the first issuance of mortgage-backed securities guaranteed by Fannie Mae—a private company, unlike Ginnie Mae—whose guarantee was perceived as an implicit guarantee by the US government, as Fannie Mae was seen as too big to fail.

Furthermore, as mortgage loans could be repaid early, it was difficult for investors to know when they would be repaid. Lewis Ranieri and Larry Fink of First Boston Bank provided a solution to the problem with the creation of the first CMO[7] in 1983, whose most « junior » tranches were the first to be subject to early repayment, thereby making the « senior » tranches sufficiently immune to the problem.

For investors, the securities created by securitization offered the appeal of higher yields than corporate bonds for what appeared to be similar risk. Apparently, because they were based on ratings from rating agencies that did not reveal the nature of the risk, i.e., the extent to which it was a specific risk independent of the market (diversifiable) or, on the contrary, systematic (market-related, non-diversifiable). However, the nature of the risk is an important factor in determining the expected return on an asset and therefore in determining its price. If we follow the logic of the CAPM[8], the expected return on an asset by an investor with a diversified portfolio depends solely on the systematic risk of that asset. Given that the credit risk expressed by a rating takes into account specific risk, comparing the return on an asset with its rating does not necessarily make sense. This explains why the returns on securitized securities may have appeared attractive, without necessarily being so, given their higher exposure to systematic risk. To emphasize that the rating of a securitized security is not the same as that of a corporate or government bond, rating agencies now add the suffix « sf » (for structured finance) to their ratings.

The 2007-2008 crisis led to a collapse in structured credit issuance, highlighting the weakness of their credit risk assessment. Admittedly, this was partly due to inadequate assumptions that could be corrected, such as the failure to take into account a decline in US real estate prices in the models of certain rating agencies. However, assessing the credit risk of these securities is a challenge in itself. Issuing an opinion on the credit risk of a CDO requires supporting assumptions about the correlation of defaults between underlying securities, given that the final result and the corresponding rating are highly sensitive to this. This led a group of Harvard professors to conclude in 2008 that the structured credit crisis was structural. Yet structured finance is back on the agenda.

3 – … but it is now being revived in a « simple, transparent, and standardized »form

Reviving securitization is part of the European project for a capital markets union launched in January 2015 by the new Commission chaired by Jean-Claude Juncker. The context is one in which the European Commission is driven by a sense of urgency to deliver economic results. According to its president, this is indeed« the last chance commission »(for the credibility of the European project). Reviving growth and employment are therefore the top priorities for the European Commission, which sees investment as the way to achieve this.

However, the reality is that capital markets are« underdeveloped and fragmented »in a context where most banks are undergoing a cycle of deleveraging that is not conducive to investment financing. In the United States, whose economy is of comparable size, the equity and bond markets are more than two and three times larger, respectively. In Europe, on the other hand, three-quarters of the economy’s financing is provided by bank credit. Financial fragmentation reflects the fact that financing conditions vary greatly between EU economies—due in particular to the heterogeneity of the situation of banks and public finances—excluding a number of players, typically SMEs in countries on the periphery of the euro area, from debt financing channels.

Securitization would strengthen the link between savings and investment. By creating securities with differentiated risk profiles, it would make monetary policy transmission more effective.[9]and reducing the economy’s dependence on bank intermediation, securitization facilitates the matching of savings and investment. By lightening banks’ balance sheets, securitization facilitates the production of new credit. By diversifying risk, securitization increases the debt capacity of assets.

Restoring investor confidence in securitization is therefore an interesting avenue to explore. The setbacks experienced by securitization in the United States have shown that credit risk assessment is not straightforward. Regulating securitization would ensure that this risk is effectively quantifiable. In this regard, it should be noted that recent financial theory[10] shows that securitization leads to a financial equilibrium that is more vulnerable to poor risk assessment.

For the EU, this means promoting « high-quality »securitization that offers the virtues of « simplicity, transparency, and standardization. » In particular, this means that the underlying assets must be homogeneous (mortgages with mortgages, etc.), that they must not themselves be the result of securitization (such as CDOs squared), that their history must be sufficient to support assumptions about the probability of default, that they must be reported on regularly, and that the issuer of the securitized assets must retain at least 5% of these assets on its balance sheet in order to bear the risks. The aim is therefore to improve the quality of assets eligible for securitization, reduce the complexity of this mechanism, and enable more reliable risk assessment.

Conclusion

When poorly managed, securitization plunged developed economies into crisis. When managed properly, it now appears to be a means of resolving the problem of investment and growth deficits in Europe by increasing the role of financial markets in financing the economy, particularly where the activity of these markets is still limited (as is the case with SMEs, for example).

Even though the scale of the crisis affecting securitization was less severe in Europe than in the United States[11], past abuses justify the current rehabilitation exercise being carried out by European institutions.

Notes:

[1] Probability of default on the « junior » tranche = probability of default on one of the two tranches = 10% + 10% – 10% x 10% = 19% (Poincaré formula).

Probability of default of the « senior » tranche = probability that both tranches will default = 10% x 10% = 1% (independent events).

[2] CDO stands for collateralized debt obligation, i.e., a security backed by various types of assets (loans, securities).

[3] RMBS stands for residential mortgage-backed security, i.e., a security backed by mortgage loans.

[4] The rate at which US banks lend each other the funds they hold with the Fed. This rate determines the rate at which banks can borrow funds from the Fed itself, but also, and more importantly, the value of all other interest rates in the US economy’s monetary circuit.

[5] According to former financier and writer Michael Lewis in his book Liar’s Poker.

[6] An expression meaning that certain financial institutions would be bailed out by the government in the event of difficulties because their failure would be disastrous for financial stability due to their size and interconnectedness within the financial system.

[7] CMO stands for collateralized mortgage obligation, i.e., a security backed by mortgage loans.

[8] The CAPM (capital asset pricing model) posits that the return required by an investor is not linked to total risk, but only to market risk. This model is based in particular on the assumption that all investors have diversified asset portfolios, with the result that diversifiable risk is not remunerated.

[9] That is, the fact that a fall in interest rates leads to improved financing conditions for all economic agents.

[10] A model of Shadow Banking, The Journal of Finance, 2013.

The creation of diversified loan portfolios that back the issuance of « risk-free » debt by SPVs eliminates exposure to borrowers’ intrinsic risk (i.e., risk resulting from events specific to them, such as divorce) but increases SPVs’ exposure to systematic risk (i.e., risk affecting all loans, such as a recession) and, when extreme systematic risk is underestimated, increases systemic risk (risk of deterioration or paralysis of the entire financial sector).

[11] The default rate on AAA-rated securitized securities was 0.1% in Europe, compared with 3% (prime) and 16% (subprime) in the United States.

Sources:

-The Economics of Structured Finance, Harvard Business School, 2008.

-Securitization: The Road Ahead, IMF, 2015.

-A Model of Shadow Banking, The Journal of Finance, 2013.

-Liar’s Poker, Michael Lewis, 1989.

-Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Economic Letter, December 3, 2004.

-European Union website and press releases.