Summary:

· The quality of schools impacts the stratification of populations within an area as well as real estate prices.

· In the San Francisco Bay Area in the United States, nearly 25% of the overexposure of the wealthiest to the wealthiest (i.e., a wealthy individual tends to live surrounded by other wealthy individuals) is ultimately attributable to preferences for the « quality » of schools.

However, a distinction must be made between a direct effect (due to preferences for « good quality » schools) and indirect effects (due to preferences that lead us to live among people who are similar to us). The latter effect is more pronounced than the former.

· The quality of schools also has an impact on real estate prices. In 2004 in Paris, a home that provided access to the middle school with the best exam results sold for €13,000 more than the same home ( i.e., same size, features, location, etc.) if it provided access to the worst middle school.

The start of the school year always provides an opportunity to discuss schools and how they influence economic variables. For example, the media reported on the (direct) cost of starting school (€190.24 on average for a sixth-grade student, according to the Famille de France association), and there is ongoing debate about the cost of running the national education system (€65.72 billion according to the 2016 finance bill), its effectiveness, and in particular the question of whether and how schools should prepare students for working life, etc.

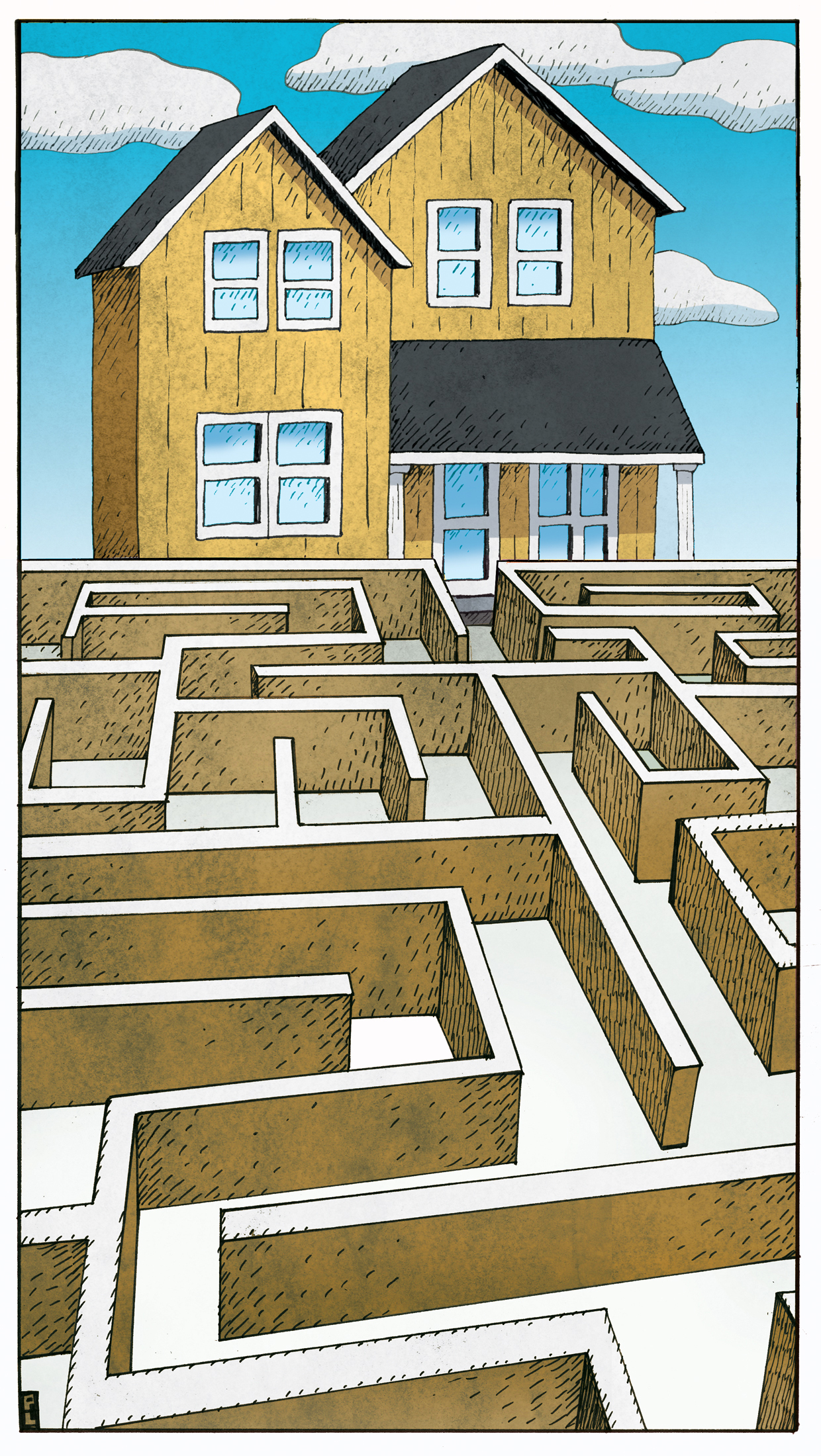

Schools and educational institutions also influence economic life through their impact on real estate markets and the residential stratification of populations. Indeed, the price of housing reflects the amenities, quality of local public goods and services, etc. that an individual can consume while residing in that housing. The quality of educational institutions plays a significant role in this capitalization process.

In concrete terms, parents most often want to send their children to schools, middle schools, or high schools with good reputations, good exam results, etc., which increases the demand for housing that facilitates schooling in the best institutions. The quest for access to the best schools triggers population movements that can ultimately reinforce residential segregation. At the same time, if the housing supply cannot respond, the price of housing in desirable locations may increase.

This article aims to highlight these two phenomena, drawing on two economic articles that study the San Francisco Bay Area and the city of Paris.

Schools and residential stratification of populations

Is the « quality of schools » (e.g., exam success rates) a factor in household mobility?

While it may seem natural for parents to seek to enroll their children in the best schools, even if it means moving, it is difficult to measure the precise impact of school quality on population movements. This requires understanding and modeling how individuals choose where to live in order to isolate the various factors involved, including the influence of schools.

In a 2007 article, Bayer, Ferreira, and McMillan use an innovative method to understand the role of schools in choosing where to live in the San Francisco Bay Area and to simulate what the population distribution would be if school quality played no role in these choices. The article therefore proceeds in two stages: (1) estimating, based on individuals’ actual choices, their (potentially heterogeneous) preferences for local public goods, amenities, proximity to the workplace, etc., as well as their preferences for social homogeneity (i.e., living near individuals who are similar to them). (2) Based on the estimated preferences, simulate the new distribution of the population assuming that school quality had never influenced individuals’ choices.

This exercise makes it possible to distinguish between the direct impact of schools on the choice of place of residence—preferences for living in an area where children can attend high-quality schools—and the indirect impact of these schools. Indeed, if individuals prefer to live among people who are similar to them (for example, wealthy people prefer to live among other wealthy people), then the preferences of certain individuals for high-quality schools (for example, wealthy parents of school-age children) will have an impact on the choices of other individuals. The opening of a high-quality school in a neighborhood may motivate wealthier individuals to move there in order to enroll their children, which may in turn encourage other parents to move there as well. They will thus benefit from the school and the presence of the first affluent families. Finally, individuals who do not have children but wish to live among affluent people may want to reside in this location.

To better illustrate their main findings, Bayer, Ferreira, and McMillan begin by showing that a person without a degree lives in a neighborhood with many more people without degrees than if the population were distributed homogeneously. Similarly, people with college degrees live in neighborhoods where people with college degrees are overrepresented. Focusing on income rather than education leads to similar conclusions.

Now, in a world where school quality played no role, the rates of overexposure to one’s own group (i.e., people without degrees to people without degrees, « rich » people to rich people, etc.) would be drastically impacted. Initially, by neutralizing the direct impact of schools (i.e., preferences for living near the best schools), we would see an 11% decrease in the overexposure of people without degrees to each other, as well as a 6% reduction in the overexposure of people with university degrees to each other. Similarly, the overexposure of the wealthiest to their own group would decrease by 12%.

Second, when we take into account the impact of the preference for living among peers in residential choices, the reduction in the overexposure of the most educated to their own group would reach 26%, and that of the wealthiest to the wealthiest would reach 27%.

The preceding paragraphs demonstrate the potentially extremely strong impact of educational institutions on residential choices and its consequences on population stratification. Unfortunately, it is difficult to know whether these figures can be applied to France, even though there is little doubt that the search for proximity to the best educational institutions also promotes residential segregation.

Estimating the impact of academic success on real estate prices

What is the effect of a good school on real estate prices? Here, the empirical challenge is to isolate the impact of school quality from other factors that affect the quality of life in a neighborhood and, therefore, the real estate market.

For example, a house « A » in neighborhood « A » may sell for more than a house « B » in neighborhood « B. » The school in neighborhood « A » may also be better than the one in « B, » but it would be wrong to attribute the price difference solely to differences in school quality, as other factors may also play a role: the quantity or quality of green spaces, the presence of sports facilities, the desire for residential exclusivity, etc. These factors influence real estate prices and, while they may have complex interactions with school quality (particularly residential exclusivity), they are not directly attributable to schools.

In some very specific cases, however, it is possible to obtain a good estimate of the effect of a school on real estate prices. Let’s take the example above again, but now suppose that house « a » and house « b » are located on the same street, opposite each other, and that the school district divides this street in two. Thus, the two houses are located almost exactly in the same place (you just have to cross the street), but a child living in house « a » will attend a different school than a child living in house « b. » By comparing the prices of these homes, we can determine the impact of a school on real estate prices.

Comparing two homes that are very close but separated by a « border » (the school map in the previous example) is the essence of the Boundary Discontinuity Design used today by many economists (including Bayer, Ferreira, and McMillan in the article described above). Gabrielle Fack and Julien Grenet (2010) were able to apply a similar approach with Parisian data covering the period 1997-2004. They show that a home whose affiliated middle school allows 67% of its students to enter a general education program will sell for 1.6% to 1.9% less than another home whose affiliated middle school allows 82% of its students to enter the general education program. Similarly, the authors calculate that an apartment allowing access to the Parisian middle school with the lowest results in the 2004 school certificate exam would be sold for 7% less (i.e., $13,000 for the average apartment in the sample – the average price in the sample is €183,000) than an identical apartment ( same size, same location, etc.) that would give access to the best middle school.

Another interesting point raised by Fack and Grenet (2010) is the substitutability between public and private schools, causing a heterogeneous impact of the « quality » of schools on real estate prices. Indeed, living « on the right side of the school map » brings less advantage if there are many private schools nearby. Thus, the 1.6-1.9% price increase discussed above would in fact be 2.5% in areas where private schools are rare and only 0.8-1.2% in neighborhoods with many private schools.

Conclusion

The « quality » of nearby schools can have a major influence on where we live. This impact can be direct, in that we want to live closer to the best schools, or indirect: even if we don’t have children and don’t take this factor into account, we may want to live among our peers (in terms of wealth, education, etc.) who choose where to live based on the quality of schools. According to Bayer, Ferreira, and McMillan (2007), more than 25% of the overexposure of the wealthiest to their peer groups can be explained by the desire to live near the best schools.

If the quality of schools is a factor influencing our choice of place of residence, it will also have an impact on real estate prices. Fack and Grenet (2010) estimate that in 2004 in Paris, the same property could have a price difference of €13,000 depending on whether it provided access to the best or worst middle school. This impact on prices also depends on the presence of private schools in the neighborhood, which act as substitutes for good public schools.

References:

Patrick Bayer, Fernando Ferreira, and Robert McMillan, » A Unified Framework for Measuring Preferences for Schools and Neighborhoods, » Journal of Political Economy, 2007, vol. 115.

Gabrielle Fack and Julien Grenet, When do better schools raise housing prices? Evidence from Paris public and private schools, Journal of Public Economics, 2010, vol. 94.