Summary:

– Over the past decade, capital flows to emerging countries have grown steadily, alternating between massive inflows and sudden outflows of foreign capital.

– The relative share of portfolio investments in capital flows has continued to grow. However, these portfolio investments are inherently volatile and can cause serious economic and financial imbalances.

– The volatility of portfolio investments, combined with the delay in publication and the low frequency of balance of payments data published by the IMF, make it difficult to prevent imbalances, particularly in exchange rates (which are closely linked to the dynamics of portfolio investments).

– The case of Brazil, which we discuss in this article, is emblematic of the current situation of emerging countries with large current account deficits.

Since 2003, capital flows to emerging countries have literally skyrocketed. Initially, this increase was largely explained by the much greater growth potential in emerging countries than in developed countries (i.e., pull factors). Secondly, in response to the 2007-08 financial crisis, the major central banks in developed countries significantly loosened their monetary policies and injected substantial amounts of liquidity into the economy. This global excess liquidity at a « good price » revived the appetite for risk among investors seeking returns (i.e., push factors). Investors naturally turned to emerging countries. However, portfolio investments (which account for an increasingly large share of capital flows) are largely reversible and can create serious economic and financial imbalances (excessive accumulation of foreign exchange reserves, asset price bubbles, exchange rate volatility, etc.). These risks are mainly present in emerging Asia and Latin America. In this article, we discuss the emblematic case of Brazil.

Portfolio investments: desirable but volatile!

The attractive returns offered by emerging markets are based mainly on the prospect of strong economic growth. Consequently, a relatively long investment horizon is necessary to reap the benefits of this prospect and thus realize capital gains. Furthermore, it is true that portfolio investments are mostly made in the short term and can also generate very high returns, particularly due to the narrowness of these markets (large investors can have a significant market impact on illiquid markets where, by definition, transactions are few and far between).

Even if the economic growth of emerging countries is essential in the medium and long term in the quest for returns by investors in developed countries, portfolio investments are crucial for the economic and financial development of emerging countries. Indeed, they contribute to greater integration of emerging markets into the global economic and financial system. In this context, portfolio investments are useful both for developed countries (seeking returns mainly through carry trades [1]) and for emerging countries (desirable and valuable financial resources to finance the real economy).

In the case of Brazil, portfolio investments mainly finance companies and industries specializing in the extraction, transport, and sale of agricultural, industrial, and energy commodities. One example is Petrobras’s massive capital increase [2] ($70 billion) in September 2010, which was financed mainly by foreign capital via portfolio investments. Furthermore, Brazil’s current account deficit remains largely financed by the financial account surplus (in which portfolio investments play an increasingly important role).

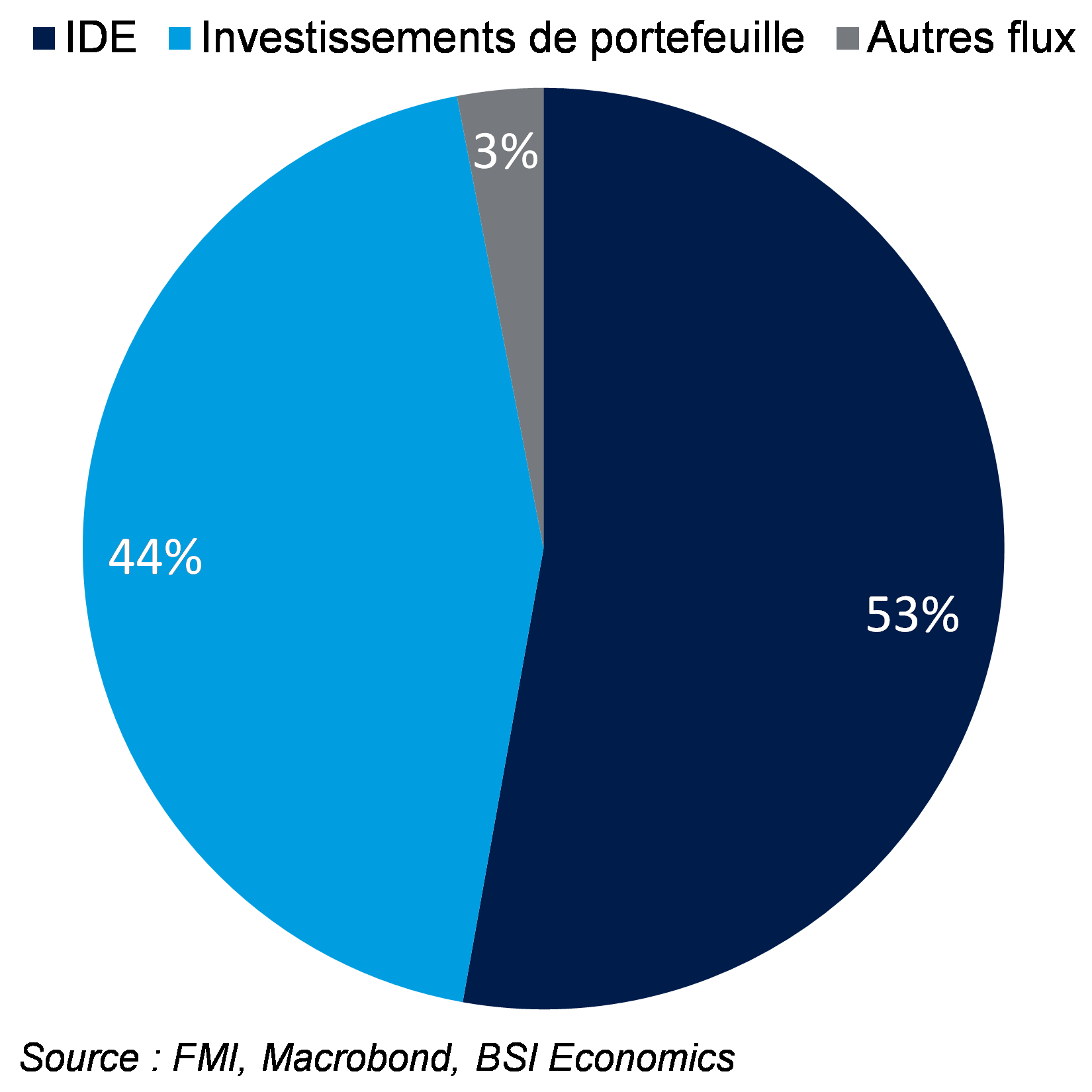

However, over the last decade, the relative share of portfolio investments in total net capital flows has only grown. In Brazil, portfolio investment accounted for an average of 44% of net capital flows from 2005 to 2012 (see chart below). These portfolio investments are inherently volatile and can lead to economic and financial imbalances (IMF, 2011a; Forbes and Warnock, 2012).

Breakdown of net capital flows to Brazil [3]

Beyond this volatility, which is mechanically induced by the investment horizon and speculation (mainly on equity portfolios), the capital flow data published by the IMF through the balance of payments have two major drawbacks. These data, widely used by academics and practitioners, are available at low frequency (quarterly at best) and with a delay of up to several quarters. In the case of Brazil, the publication delay is currently three quarters. These problems, linked to the publication of balance of payments data, coupled with the volatility of portfolio investments, make it difficult to prevent certain imbalances, particularly in the exchange rates of emerging countries. Numerous substitute or proxy variables (changes in foreign exchange reserves, capital flow trackers, coincident indicators based on private data, etc.) have therefore appeared in the academic literature, both for approximating net capital flows (Calvo et al., 2004 and 2008; Reinhart and Reinhart, 2009) and gross portfolio investments (Miao and Pant, 2012).

Beyond the findings established in this section, we may ask ourselves what kind of links exist between portfolio investments and certain financial assets in the case of Brazil.

There are strong links between portfolio investments and certain financial assets…

Emerging countries do not necessarily have financial markets that are sufficiently liquid and deep to absorb the sometimes colossal portfolio investments of non-residents. This low absorption capacity increases the risk of asset price bubbles and exchange rate overvaluation. In addition, the short-term horizon of these portfolio investments makes their often sudden withdrawal inevitable. The exchange rate is once again impacted (downward this time) and further complicates the exercise of monetary policy.

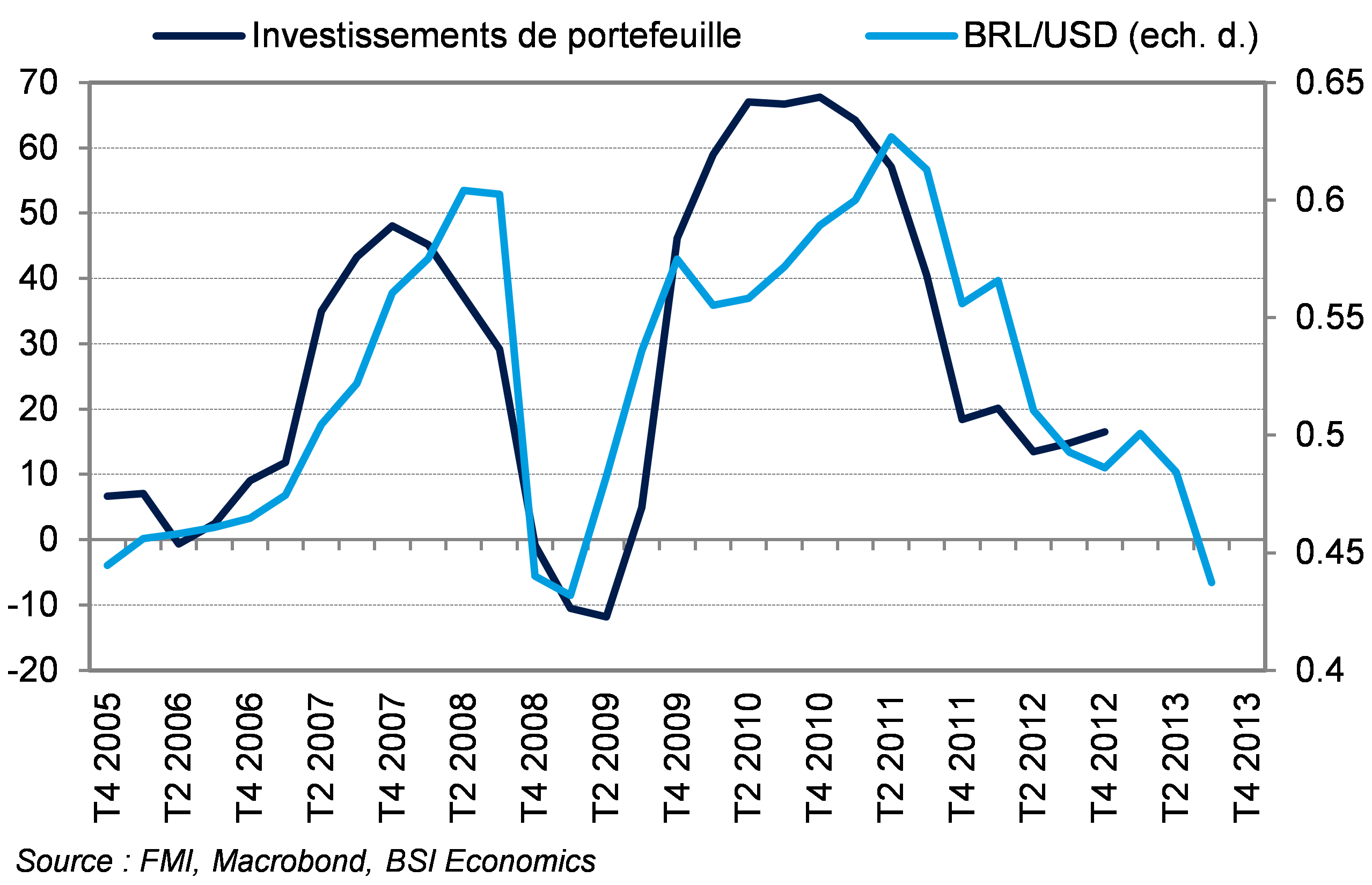

Looking at the Brazilian exchange rate against the dollar, it appears that movements in the real are strongly correlated (around 80%) with portfolio investment dynamics (see chart below).

Gross portfolio investment in Brazil vs. exchange rate against the dollar [4]

If the correlation highlighted here continues over the recent period, it appears that portfolio investment is struggling. Since Ben Bernanke’s speech on May 22, there have been significant capital outflows from emerging markets (see our article on this subject, » When the Fed sneezes, emerging countries catch a cold, » by the same author), and Brazil has not been spared…

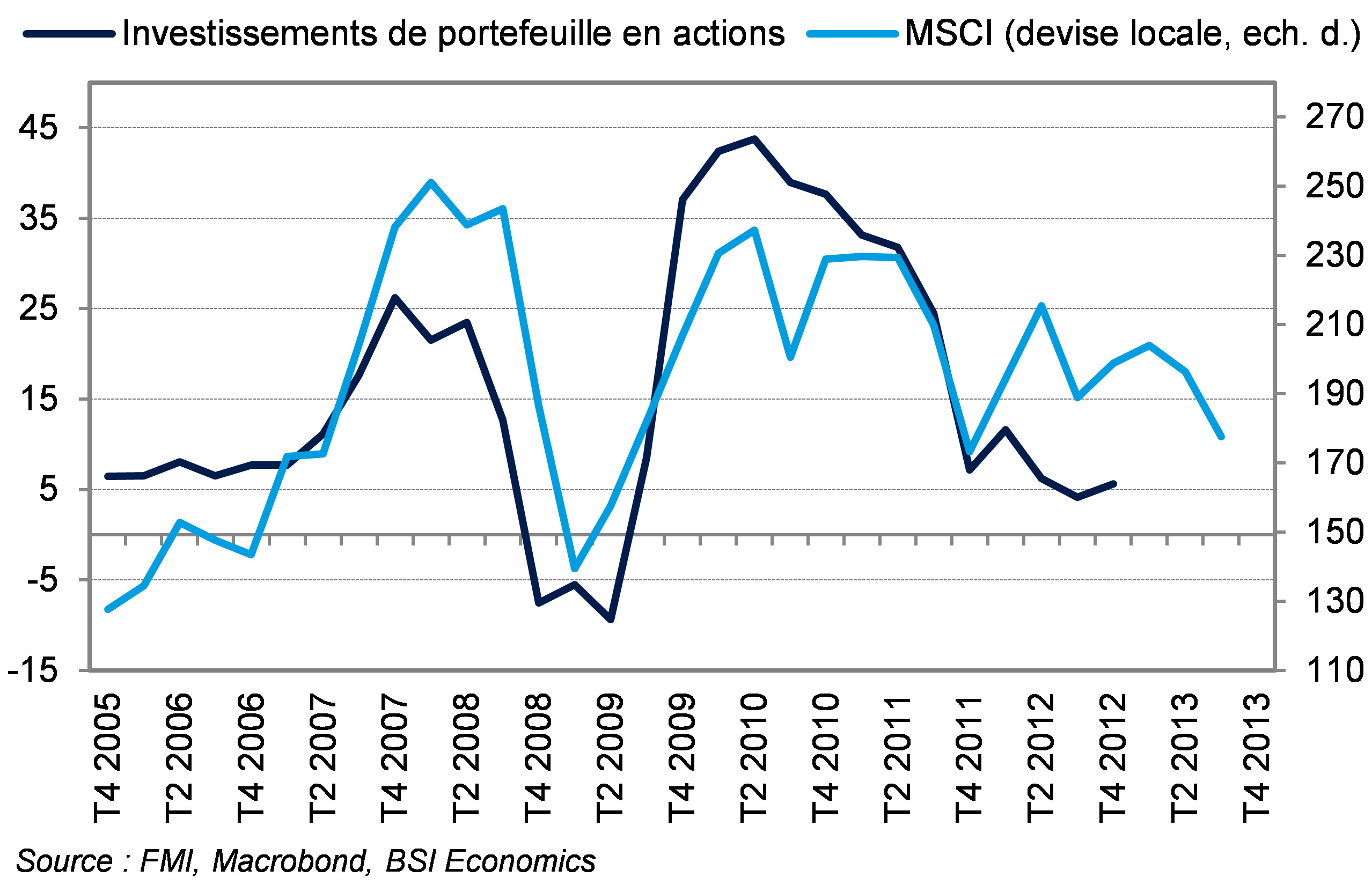

In addition to this strong correlation between portfolio investments and the exchange rate against the dollar, it is interesting to note that the dynamics of portfolio investments in equities (as opposed to portfolio investments in bonds) are highly correlated (around 70%) with the performance of the Brazilian equity markets [5] (see chart below). These portfolio investments in equities (roughly the same size as portfolio investments in bonds over the entire period [6]) obviously follow the downward trend in portfolio investments as a whole, thus corroborating the decline in Brazilian equity markets.

Gross portfolio investments in Brazilian equities vs. MSCI [7]

Emerging countries are therefore facing high volatility in portfolio investments, resulting in particular in increased instability in their exchange rates and equity markets, which can lead to the emergence of asset price bubbles. How can this heightened procyclicality of portfolio investments be addressed? Apart from policies to accumulate foreign exchange reserves, which are proving increasingly costly because they have to be sterilized by central banks, some emerging countries have introduced capital controls. This is the case in Brazil, which, thanks to its tax on financial transactions (IOF), was able to control short-term capital inflows when they rose sharply in 2007-08, withdraw this tax at the onset of the crisis, and then reintroduced it during the last wave of capital inflows in 2009-10. Very recently, the IOF was suspended on portfolio investments in bonds in order to attract investors back to this asset class. In addition, last April, the Brazilian Central Bank (BCB) began a cycle of monetary policy tightening by raising its main policy rate (Selic) by 225 bp to 9.50%. Finally, the BCB announced a vast program worth $54 billion between now and the end of the year in the form of credit line swaps to support its currency.

Conclusion

Thus, over the last decade, portfolio investments, beyond their volatile nature, have maintained real links with certain financial assets (e.g., exchange rates and equity markets). We are therefore entitled to ask which variable is likely to explain the other. The IMF (GFSR, 2010) has shown that, over the long term, capital flows are partly explained by an increase in returns, but that returns are themselves caused by capital flows. Brazil’s desire to implement capital controls in order to curb capital inflows and limit the appreciation of the real is not really a choice. According to Mundell’s (1960) incompatibility triangle, it is theoretically impossible for a country to reconcile free movement of capital, monetary policy autonomy, and exchange rate pegging. In Brazil’s case, monetary policy autonomy is essential, particularly in order to effectively combat rampant inflation. Furthermore, abandoning exchange rate stabilization could prove very dangerous. In this context, capital controls (IOF) appear to be a convincing alternative in the fight against the pernicious effects of portfolio investment volatility.

Bibliography:

– Calvo, G. A., A. Izquierdo, and L. F. Mejia, 2004, “On the Empirics of Sudden Stops: The Relevance of Balance-Sheet Effects, » Proceedings, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Jun 2004.

– Calvo, G. A., A. Izquierdo and L. F. Mejia, 2008, “Systemic of Sudden Stops: The Relevance of Balance-Sheet Effects and Financial Integration,” NBER Working Paper No. 14026, May 2008.

– Forbes, K. J. and F. E. Warnock, 2012, “Capital Flow Waves: Surges, Stops, Flight and Retrenchment,” Journal of International Economics, Elsevier, Vol. 88(2), pp. 235-251, November 2012.

– International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2010, Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR), “Sovereigns, Funding, and Systemic Liquidity,” October 2010.

– International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2011a, “Recent Experiences in Managing Capital Flows: Cross-Cutting Themes and Possible Policy Framework,” IMF Board Paper, Strategy, Policy, and Review Department, February 2011.

– Mundell, R. A., 1960, “The Monetary Dynamics of International Adjustment under Fixed and Flexible Exchange Rates,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 74(2), pp. 227-257, May 1960.

– Natixis Economic Research, 2013, “A Case for Capital Controls in Emerging Countries,” Natixis Flash Structural Issues No. 738, October 2013.

– Reinhart, C. M. and V. Reinhart, 2009, “Capital Flow Bonanzas: An Encompassing View of the Past and Present,” NBER Chapters, in: NBER International Seminar on Macroeconomics 2008, pp. 9-62, April 2009.

Notes:

[1] Defined as a speculative transaction on yield spreads.

[2] Petrobras is a Brazilian oil extraction, refining, transportation, and sales company. It is the largest company in Brazil and is currently one of the 15 largest oil companies in the world.

[3] Average from Q1 2005 to Q4 2012.

[4] Gross portfolio investments in Brazil represent only the liabilities side of the balance of payments. They are recorded in billions of dollars and reported as a rolling total over four quarters in order to better reflect the investment dynamics of foreign investors. The BRL/USD exchange rate is reported as a quarterly average for comparison purposes.

[5] Brazilian equity markets are approximated by the MSCI (Morgan Stanley Capital International) Brazil index in local currency. This index is widely used by practitioners to report on the overall performance of a sector or, in this case, a country.

[6] However, we note a slight preponderance of portfolio investments in bonds in the recent period. This is explained by the tendency of investors to diversify their bond portfolios in the current environment of yield seeking.

[7] Gross portfolio investments in Brazilian equities represent only the liabilities side of the balance of payments. They are recorded in billions of dollars and reported as a rolling four-quarter total for the reasons stated above. The MSCI Brazil in local currency is reported as a quarterly average for comparison purposes.