DISCLAIMER: The person is speaking in a personal capacity and does not represent the institution that employs them.

Summary:

– The interaction and interconnection of individually sound financial entities is a source of new vulnerabilities, which require a more comprehensive approach to risk management.

– However, systemic risk is a very difficult concept to define, which makes it all the more difficult to measure as there is no point of comparison.

– Rather than seeking to quantify this new risk and predict its materialization, the objective, albeit less ambitious, is to identify vulnerabilities so that they can then be managed in real time using macroprudential instruments, most of which are still to be finalized.

The Financial Stability Board (FSB) is preparing to publish a revised list of G-SIBs(Global Systemically Important Banks), i.e., a ranking of banks that could jeopardize the stability of the global economy, providing an opportunity for a critical analysis of the approach used to measure this so-called « systemic » risk. The Great Recession of 2007 raised awareness of the limitations of banking regulations focused on the behavior of individual institutions; the interaction and interconnection of individually sound entities is a source of new vulnerabilities that require a more comprehensive analysis of risks, without which it is illusory to hope to understand the crises we are currently experiencing.

In the words of 1973 Nobel Prize winner Wassily Leontief, « like fabric before it is cut, observed facts have no shape until they are analyzed. » But what kind of analysis? This article offers a framework to keep in mind in order to better understand systemic risk.

Macroprudential policy and systemic risk: heads or tails?

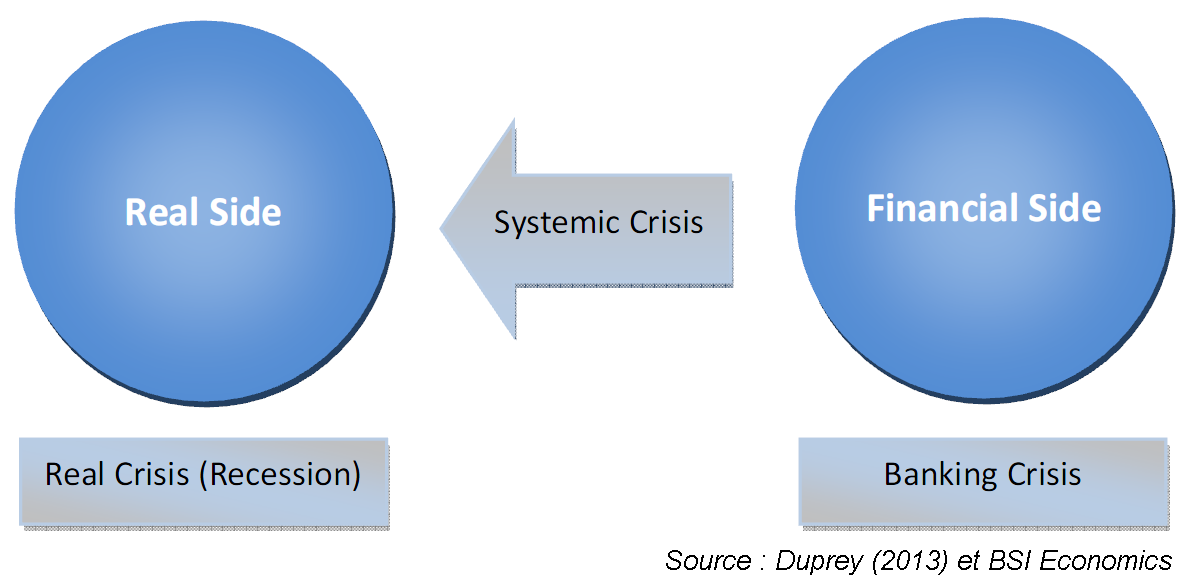

The vast undertaking of reforming banking and financial supervision aims to supplement traditional microprudential regulation, i.e., regulation focused on individual risks, with macroprudential analysis that takes into account risks as a whole, i.e., regulation focused on systemic risk. The primary objective of the new macroprudential policies is thus to avoid, as far as possible, crises that jeopardize the stability of the financial system, i.e., the ability of banks to finance the economy, and which, due to their scale, would have a significant real macroeconomic cost (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Definition of a systemic crisis

From this perspective, the two main objectives of macroprudential policy (CGFS, 2010) are (i) to discourage individual risk-taking that imposes negative externalities on other financial actors and (ii) to limit the underestimation of individual risks during expansionary phases—a phenomenon known as the « paradox of tranquility » (Minsky, 1970). Macroprudential policy is therefore a policy that aims to limit the risks weighing on the financial system as a whole without being internalized by the individuals who comprise it. Macroprudential policy and systemic risk are therefore two closely related concepts, with risk measures (e.g., Bisias et al., 2012) enabling the implementation of carefully calibrated tools.

However, the quest for a measure of systemic risk is fraught with pitfalls; some of these pitfalls are outlined here (for more details, see Section 5 and Appendix D Bennani et al., 2013).

What are the dimensions of systemic risk?

Systemic risk can be defined (see previous article here) as « the risk that financial instability will become so severe that it prevents the financial system from functioning properly, to the point of negatively impacting growth and well-being » (ECB, 2010, p.138). More specifically, systemic risk would therefore reflect:

- Common exposures to the main risk factors (also known as systematic risk);

- Contributions to the rise in systemic risk;

- Contagion linked to the interconnection between financial institutions.

The various aspects of systemic risk can be divided into two main dimensions: (i) the stability of the system at any given point in time, whether the shock is endogenous (systemic in the restrictive sense) or exogenous (systematic); and (ii) the stability of the system over time, i.e., the possible amplification of the initial shock (procyclicality). The resilience of the system can therefore be undermined by a small initial shock that is amplified and transmitted to all institutions. Measuring such systemic risk poses the following challenge: proposing a comprehensive approach to risks, which must be investigated in as much detail as possible.

Which « system »?

Systemic risk analysis requires defining what is meant by « system. » It consists of a set of institutions, not necessarily exclusively banks, spread across a relevant geographical area. The system in question is comparable to a portfolio of assets whose cross-performance is analyzed. A difficulty arises: any measurement of systemic risk depends on the sample selected, since it involves studying interactions, which makes it difficult to compare results.

What type of data?

The opposition is between market data and balance sheet data; while market price valuation allows the use of long time series with high frequency, this assumes that the market accurately captures systemic risk and associates a price with it, even though systemic risk is by definition an externality, i.e., an event that has a significant impact on the behavior of others but does not give rise to financial compensation, in other words, without the price being internalized.

Conversely, the use of balance sheet data or macroeconomic aggregates with a lower frequency should make it possible to better track the evolution of systemic risk over time. However, balance sheet data are not always comparable, for example due to differences in the treatment of derivative positions between the IFRS accounting standards applied in Europe and the GAAP standard used in the US. Can we therefore reasonably believe that European banks use 2 to 3 times more leverage than US banks? [1]

Furthermore, how can balance sheet data or macroeconomic aggregates be compared with other data available at a higher frequency? On the one hand, interpolation makes it possible to obtain smooth series over time, but it imputes data that has not yet been observed, and will only be known at the end of the period, to the current period, which amounts to falsely introducing a predictive element into the measurement. On the other hand, using macroeconomic predictions to complete the series with the last point may seem attractive, but the behavior of the last point is crucial in determining a trend; for example, the difference between the quantity of credit supplied and its long-term trend can sometimes be entirely explained by subsequent revisions of national statistics.

More generally, most analyses are limited by the use of public data, in the absence of centralization or access to regulatory data. Several initiatives by supervisory authorities are therefore aimed at improving data collection and making data available at the relevant level (notably the G-20 Data Gaps Initiative led by the Financial Stability Board).

What “building materials”?

Correlation, co-movement, and conditional probabilities are not synonymous with causality! The shortcut is sometimes tempting, but it assumes strong preconceptions about possible explanations. For example, conditional probability measures of default may well increase if the anticipated frequency of occurrence of the conditioning event decreases [2], which may reflect both an increase in extreme risk and a decrease in the likelihood of an extreme scenario occurring.

In order to move on to an analysis in terms of causal relationships, it is often necessary to impose more structure by using more difficult-to-justify parametric assumptions aimed at modeling the underlying process, and not just the co-movement of observed variables. For example, multi-agent approaches or behavioral analyses assume a bank’s decision rule regarding the evolution of its balance sheet in order to identify the transmission channel and chain reactions on other financial institutions.

How can the results be verified?

Ideally, every analyst would like to confirm their forecasts…

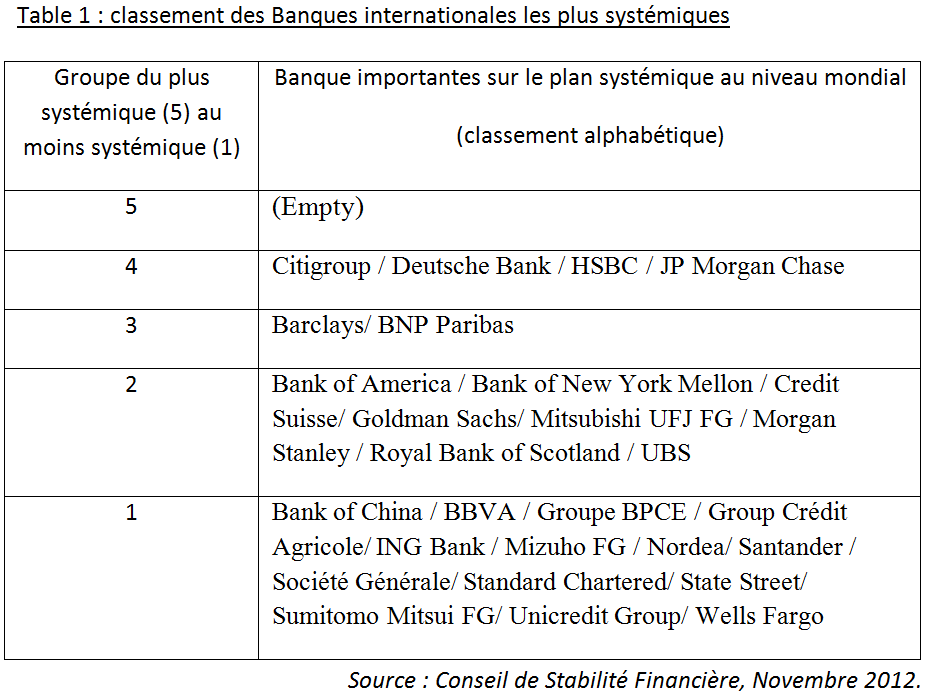

For a cross-sectional analysis, we could take into account the official ranking (see Table 1) of systemic financial institutions published by the Financial Stability Board. However, this ranking does not necessarily reflect the systemic importance of the institutions concerned, and also includes the subjectivity of the economic and political leaders who authorized its publication. Furthermore, in the absence of alternatives, it would be desirable to test the robustness of the analyses, particularly the resulting rankings. Unfortunately, most current measures do not provide any confidence intervals.

Table 1: Ranking of the most systemic international banks according to the Financial Stability Board

Furthermore, while it is difficult to compare the measures with each other, it may be preferable to verify the internal validity of the results by comparing them with events identified as systemic [3]. But this takes us from a quantitative approach to a qualitative analysis, which itself failed to identify the rise in risks before 2008…

In short, a systemic risk measure theoretically measures what it was designed to measure, but generally does not allow for any absolute or relative comparison with other alternative methods or between institutions within the same system.

Where do we stand?

While it is now possible to measure the size of a shock ex post and track its evolution, real-time monitoring or « now-casting » of the evolution of systemic risk as we emerge from the crisis already requires a good deal of confidence in the tools used. But what about ex ante estimates of the accumulation of vulnerabilities in the financial system? Distinguishing between excess credit and leverage and the increase in debt and credit allocation capacity made possible by efficiency gains in the financial industry is now a matter of guesswork, as current tools provide only very limited predictive power.

Given (i) the difficulty of identifying the various facets of systemic risk, (ii) the current pace of financial innovation, and (iii) the difficulties in developing early warning indicators, the new macroprudential regulation can only be effective if the regulator itself retains a margin of interpretation over the systemic risk measures currently at its disposal and a certain flexibility in the calibration of the new prudential tools.

Notes:

[1] Quasi-leverage, i.e., the ratio of liabilities (debt) to capital (equity), is almost three times higher for BNP and Société Générale than for CitiGroup and Morgan Stanley. as of December 31, 2012 (Bloomberg data), it stands at 34 and 54 for one, respectively for BNP and Société Générale, compared to 14 and 18 for one, respectively for Citigroup and Morgan Stanley.

[2] The conditional probability of institution A going bankrupt if country B defaults is written as: P(A|B) = P(A∩B)/P(B). However, this conditional probability may increase if the frequency of bankruptcy in country B, denoted P(B), decreases. Even if the probability of bankruptcy in country B decreases, the probability of a joint bankruptcy of bank A and country B, denoted P(A∩B), may not decrease as much if the links between A and B are strengthened, which may be the case since we are now looking at the interaction between A and B in an even more extreme scenario where it is more likely that both will go bankrupt at the same time. Admittedly, in the event of a shock to country B, bank A will certainly fail, but the probability of facing this extreme scenario is all the lower, which may suggest a certain improvement in the situation.

[3] For example, using the « Systemic Banking Crisis Database, » IMF, 2012.

References:

– Duprey, T. (2013). Measuring and modeling systemic risks: where do we stand? Presentation prepared for the International Banking and Finance Institute.

– Duprey, T. (2013). In search of a definition of systemic risk, BSi-Economics.

– Bennani, T., Després, M., Dujardin, M., Duprey, T., and Kelber, A. (2013). Macro-prudential Framework: key questions applied to the French case, forthcoming Banque de France discussion paper.

– Bisias, D., Flood, M., Lo, A., and Valavanis, S. (2012). A survey of Systemic Risk Analytics. Office of Financial Research Working Paper No. 0001.

– Committee on the Global Financial System, 2010. Macroprudential instruments and frameworks: A stocktaking of issues and experiences. CGFS Publications No. 38.

– European Central Bank, 2010. Financial Stability Review. June 2010, pp. 138-146.

– Minsky, H. (1986). Stabilizing an Unstable Economy. Yale University Press.