Questions are mounting about the benefits of further quantitative easing by central banks relative to the associated costs. The marginal cost of quantitative easing programs would outweigh the benefits (lower uncertainty premium, low real interest rates, and wealth effect on consumption). This marginal cost would be estimated based on five effects. (1) The divergence from fundamentals, which is reflected in the weak correlation between equity performance and earnings revisions (equity markets), between investment grade credit spreads and economic uncertainty or inflation expectations (bond markets), and low volatility despite a strong correlation between asset classes. (2) The distortion in asset allocation, with active strategies losing assets under management (-$400 billion) to passive or alternative strategies (+$500 billion and +$600 billion, respectively). (3) The strong relationship between liquidity injections and the performance of both equity and bond markets. (4) The widening wealth gap, with weak pension funds and savings products limiting, among other things, the wealth effect via consumption. (5) The weak correlation between credit growth and economic growth, particularly in the eurozone. Furthermore, a low interest rate environment would favor investment, although the rebound, particularly in the non-residential sector, would remain limited given the low utilization of productive capacity, weak real productivity, and low producer prices. The fall in real interest rates would also be offset by the rise in asset costs, with a particular increase in the risk premium for equities. The marginal benefit of more QQE would therefore become lower than the marginal cost of this policy, according to this type of analysis.

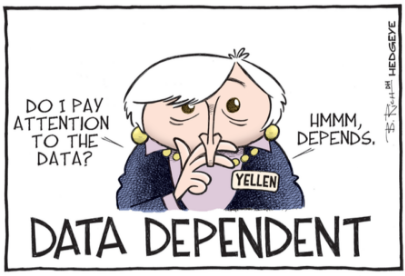

The question of a rate hike on September 20 remains relevant after Jackson Hole, with a 60% probability of a 25bp hike in 2016 and a 33% probability of a 25bp hike in September. Market pricing is based on two comments, one from Janet Yellen characterizing the possibility of a hike as « strengthened » and the second from Fischer considering that the first comment was consistent with a hike in September. Secondly, US employment was weaker than anticipated for August but revised upwards for July, even though the latter figure had been a big surprise on the upside, confirming a potential strengthening of the labor market and therefore maintaining the possibility of a rate hike as early as September. Finally, the US political calendar does not historically influence the Fed’s monetary policy decisions. A rate hike in September would mean that the Fed would not have to provide further explanations for postponing a hike at its press conference, thereby avoiding any questioning of its communication policy and the credibility of the institution. However, inflation and economic targets, along with a possible deterioration in the long-term economic outlook, could also justify maintaining the status quo.