A Social Union to overcome inconsistencies

Summary:

– European economic governance does not allow for an effective resolution of the crisis. It could even have very significant costs.

– Europeans have a choice to make: reject European integration or launch a political union. This is what Rodrik’s trilemma teaches us.

– The first option would mean Europeans getting pushed to the sidelines economically and politically.

– The creation of a Social Union would be the most appropriate solution because it would be legitimate, effective, and would allow for the creation of a strong common identity.

In light of the observations we have made in previous articles (Part I, Part II and Part III), the long-term economic viability of the eurozone would be called into question: neither the market nor the institutional tools currently allow member states to cope with asymmetric shocks. In this final part, we will attempt to outline a solution for the eurozone that would enable optimal stabilization of asymmetric shocks and turn the EMU into an EMU.

Political leaders disagree on the method to be followed. Northern European countries (and not just Germany) pass moral judgment on the behavior of southern countries, while the south believes that the institutional system is at fault. This deep division between the two camps undermines mutual trust and prevents an effective resolution of the crisis. Nevertheless, the urgency of the crisis has necessitated an update of governance to address the most pressing symptoms without necessarily tackling the root causes of the problem. The new governance is not yet optimal.

The mutual insurance model

Numerous reforms have been implemented to correct the governance of the Maastricht EMU: first steps towards a Banking Union to resolve the problem of « doom loops » between sovereign and bank securities, creation of the European Stability Mechanism to provide a crisis management tool, adoption of the Fiscal Compact to strengthen the SGP, ex ante control of national budgets, monitoring and control of macroeconomic imbalances through the implementation of the European Semester and the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure, quasi-automatic sanctions in the event of non-compliance with the rules, etc.

This new model of governance confirmed the intergovernmental shift that began with the Maastricht and Lisbon treaties. This new and original method, called the « mutual insurance method » by Jean Pisani-Ferry, combines solidarity mechanisms (the ESM, but also the contractualization of economies associated with the ECB’s OMT program) with very strict conditions. The logic of mutual insurance differs from the Community method [1] because national governments are subject to legal constraints and political objectives (Jean Pisani-Ferry, 2012).

The legal constraint lies in the incomplete nature of the eurozone. Unlike the EU, the eurozone had neither the financial resources nor the specific institutions to manage a crisis [2]. The political objective (or constraint?) stems from the desire of Member States not to delegate more power to Community institutions by transferring additional parts of their sovereignty. This reasoning is quite logical, since European integration is encroaching on the core of state sovereignty (fiscal policy, employment policy, social protection, etc.): it is therefore inevitable that it is the states that play the role of political entrepreneurs. Automatically, the response to the crisis has been a patchwork of intergovernmental measures.

Problems associated with mutual insurance

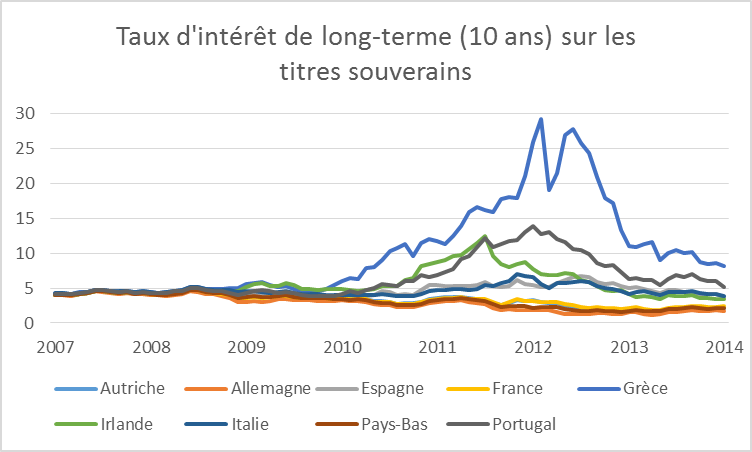

Firstly, this intergovernmental model is characterized by its relative inefficiency. Indeed, the only measure that has had a lasting effect is the speech given by Mario Draghi, President of the ECB, in July 2012. At a conference in London, he pledged to do « whatever it takes » to save the euro. Since that famous speech, interest rates on sovereign bonds have substantially converged (see chart below), giving governments time to implement reforms in a less uncertain environment. This speech is all the more powerful because, for the time being, the mere threat of acting as lender of last resort has calmed the markets (this is the Outright Monetary Transactions program).

Chart 1. Proxy for measuring the effectiveness of the intergovernmental method

Source: ECB, BSI Economics (2013)

The intergovernmental method only allows for the use of soft medicine, whereas the eurozone needs the atomic weapon. Spreads on sovereign bonds narrowed after certain « last chance summits, » but they have systematically widened again. The intergovernmental method does not solve the problem of the eurozone’s economic suboptimality.

Rodrik’s trilemma

To understand why this governance is suboptimal, it is interesting to study the lessons of Rodrik’s trilemma. Rodrik teaches us that it is impossible to have advanced economic integration, nation states, and democracy (meaning that voters have the power to influence economic policy) at the same time.

When a country accepts the rules of globalization, it gradually loses all room for maneuver in its economic policy choices. Once it accepts market laws to promote its economic development, it finds itself locked into a « golden straitjacket. » The golden straitjacket reduces economic policy choices because global market forces are too powerful to be countered by a small national entity. As long as monetary and fiscal policy management remains impervious to domestic political pressures, this balance remains stable. This is why it is difficult today to see any real differences between right-wing and left-wing governments once they are in power: this is where « democracy » is sacrificed.

The Bretton Woods compromise (fixed exchange rates, capital controls, and limited trade liberalization) was an intermediate solution that reconciled growth, nation states, and, above all, democratic economic policy choices. It should be remembered that this compromise was put in place to avoid the disastrous consequences of the gold standard system of the interwar period, which had the effects we know in Europe[3]. Although the situations are not comparable, the euro is often considered to be a replica of the gold standard system (see Eichengreen (2012), who develops this interesting thesis).

Rodrik’s trilemma can quite easily be applied to the situation in the eurozone, which is a situation of extremely advanced economic integration involving nation states. Citizens would therefore have no say. All countries adopt the same economic policies at the same time, whether they are at the heart or on the periphery of the EMU, and regardless of their respective positions in the economic cycle. Democratically elected governments that refuse to bow to European market discipline are overthrown.

The balance in which the eurozone finds itself is unsustainable in the long term because it is politically illegitimate and economically inefficient for the eurozone: in this sense, the mutual insurance model is suboptimal. It is now time for Europeans to make a choice to find a path to a stable equilibrium.

Return to the protective and closed nation-state?

The first possible alternative equilibrium is therefore « nation state – democracy, » with the following question: should we reject European integration and regain control over the national economy? This seems to have been the response of citizens across Europe for several years. Anti-European populism is on the rise, as is sovereignty, while popular support for the EU has been steadily declining since the crisis began: 52% had a positive perception in 2007, compared to only 30% in 2013, while the negative perception of the EU doubled over the same period. The same is true for the EMU, although the dynamics are less pronounced. However, outright rejection of European integration would be contrary to the interests of the European people.

(Re)Fragmenting Europe would have two consequences. First, it would mean that Europeans would certainly lose their voice in the concert of nations: whenever Europe is divided, it is unable to impose its economic and social preferences. We have seen this phenomenon at work during recent conferences on the environment, in the solar panel dispute with China, in trade discussions with the United States, and elsewhere. If Europeans want to impose their own standards on the rest of the world, they will certainly not achieve this by dividing themselves. The European Union is the most developed economic zone, the leading trading power, with the largest market in the world and 500 million consumers. If Europe is united, it can impose its values because other countries need its market.

The new wave of globalization that has been taking place since the 1990s is associated with Europe’s rapid loss of influence in the world as new countries emerge. The combination of these two events has produced a very strong identity crisis in Europe and led to the rejection of globalization for some. From a very long-term historical perspective, a world in which Europe is the leading global power is an anomaly. The challenge for Europe and Europeans is to avoid imploding during the transition period and to converge in an orderly manner towards this new global equilibrium.

Secondly, rejecting European integration would weaken European countries economically in a globalized world. To create additional growth and sustain the wealth of European populations, European countries need enormous innovation and productivity. In order to secure a high position in global value chains, it is necessary to constantly push the technological frontier. Globalization provides incentives for innovation because it offers protection from global competition. Europeans must succeed in increasing the size of the global pie if they want to maintain a certain standard of living for the future. The momentum is no longer in Europe, and accepting this new reality would allow us to move forward.

Moving from the nation state to supranational federalism?

The second possible balance is « economic integration – supranational democracy. »

First, let us remember that the new logic of mutual insurance (balance between economic integration and nation-state) would require extreme and lasting flexibility and rigor in national economies (which is already happening, see second article) in order to be stable. This is because stabilization through fiscal policy is weak in the new economic governance: market adjustment must therefore be facilitated.

Furthermore, in order to regain competitiveness after an adverse asymmetric shock, all European countries would embark (are already embarking?) on a race to the bottom in terms of social welfare: since nominal exchange rate adjustment is not possible, unit labor costs must be reduced (see article II), even though European populations aspire to a certain level of social protection. The consequences, to use the expression coined by Sofia Fernandes and Kristina Maslauskaite (Notre Europe), would be « social dismantling. » It is reasonable to question the political legitimacy of such a long-term process, which negates the European way of life: most European countries’ constitutions mention the existence of social protection rights. The open market economy is accepted on condition that solidarity mechanisms exist to compensate for inequalities.

A balance where decisions are taken at the supranational level would allow Europeans to regain control over their economic policies. The loss of national sovereignty would be offset by the creation of a supranational democracy. To achieve this balance, it is not enough to have an economically efficient system combined with federalism in order to declare that the system is democratic. Above all, this system must be politically legitimate in the eyes of Europeans and lead to the creation of a common identity. Only after this step can the EU become a federation: elections will lead to the establishment of a democratic majority with specific economic policy choices, and the losers will accept the election results, as is the case in all member states. Deciding tomorrow on a fiscal union without really thinking about the European project or European identity would be pointless. Imposing it would also be dangerous. So how can these two conditions be reconciled?

A Social Union for a Europe that protects its social heritage

It follows quite directly from what we have just said in this article and the three previous ones that the optimal solution would be European unemployment insurance, a Social Union for Europe. Today, Europe is essentially a Single Market, but the mechanisms of solidarity that exist in all Member States are absent at the supranational level, resulting in economic inefficiency and political illegitimacy.

The growing rejection of the current EU can easily be understood as a challenge to the European project, which dates back to 1950 and is no longer suited to today’s world. Peace is assured in Europe, but we are now witnessing what Gene Frieda calls a « clash of generations. » The younger generations fully understand that war has disappeared from the European continent. The EU is therefore unable to mobilize popular support for a project that has already been achieved. The creation of a Social Union would make it possible to update this European project by presenting the EU as the protector of Europe’s social heritage in the face of globalization. This Union would thus make it possible to create a positive common project and promote the emergence of a strong European identity.

Creating unemployment insurance at the European level is an effective way to provide a stabilizing mechanism against asymmetric shocks. The originality of the system lies in the fact that transfers would be made directly between European workers and unemployed people, rather than between countries. The development of common social rules, decided collectively, would avoid the establishment of a non-cooperative balance of social lowest common denominator.

The system would allocate resources to those who have been unemployed for less than a year, in order to avoid the moral hazard problem inherent in insurance systems. By limiting insurance to cyclical unemployment, this risk is de facto limited. Knowing that they will have to take over for their unemployed who have been out of work for more than a year, countries benefiting from this system retain their incentives to reduce long-term unemployment rates. The idea is therefore to establish a common European foundation, which can be supplemented by each national system according to individual preferences. European unemployment insurance thus partially replaces the national system. Although a certain level of harmonization is necessary, this in no way means the end of national unemployment insurance systems. These are in any case too different to achieve perfect standardization.

In terms of resources, each European employee would contribute to this European unemployment insurance through a European institution authorized to collect contributions. This contribution is not additional and does not increase national payroll costs. In terms of expenditure, unemployed persons who have been unemployed for less than one year would receive a benefit corresponding to x% of their last gross salary, of which y% (where y is less than x) would be paid by the European agency. After one year, however, benefits would depend entirely on the system of the unemployed person’s country of residence. Neither the replacement rate (x remains the same) nor the contribution rate would change: this is simply a transfer of prerogatives and mutualization of risks in order to avoid jeopardizing the European social model.

Taking an allowance equal to 50% of the unemployed person’s last gross salary and a level of employee contributions at 3% of gross salary for the working population, our simulation shows that the net amounts transferred would be fairly limited as a percentage of GDP for most countries. The eurozone as a whole would be in balance. However, there are some countries that would be net creditors and debtors (Spain in particular) to a greater extent. It would therefore be necessary to put in place correction procedures to prevent these permanent transfers from taking place. The system we are proposing here is neutral over the cycle, i.e., it does not give rise to permanent transfers between the different participating countries, as is the case with structural funds. This condition is absolutely necessary from a political point of view, and the Social Union respects it since it functions as an automatic stabilizer.

Furthermore, in order to receive European allowances for a period of time t, a country must also have contributed to them for an identical period of time t. This measure will be necessary to take into account national differences in the response of unemployment to an asymmetric shock.

For automatic transfers to be possible, they must be calculated on the basis of an objective variable that can be observed in real time and measured: the number of unemployed people meets all these characteristics. If they were not paid directly to the unemployed, the transfers would be subject to a certain degree of political uncertainty, and the funds could be used for purposes other than stabilization (paying interest on public debt, for example). In addition, there would be a delay before these funds were actually transferred to the real economy. Thanks to European unemployment insurance, they are paid directly where they need to be, quickly and without delay, since as soon as a new worker registers as unemployed, the transfer is triggered and immediately supports their demand. The transfer thus coincides perfectly with economic reality. The system targets those agents with the highest marginal propensity to consume, thereby maximizing the stabilizing effect on economic activity.

Conclusion

In this series, we have shown that macroeconomic stabilization of asymmetric shocks is essential for the functioning and viability of the euro area. Asymmetric shocks do exist within the EMU, and this situation does not seem to be improving over time, as the specialization of economies appears to increase their occurrence.

The question was whether stabilization was sufficient to ensure that the costs of monetary integration did not outweigh the benefits. However, it appears that neither the mechanisms nor the institutional tools allow for effective stabilization in the euro area. This therefore raises the risk of the EMU breaking up.

Member States have put in place a new economic governance system that is still suboptimal and appears to be very costly. Political constraints on economic integration prevent any effective resolution of the crisis. Europeans now find themselves in a dilemma: either reject integration and return to national sovereignty in order to manage asymmetric shocks, or take the opposite path of political integration.

The first option would mean Europeans being economically and politically marginalized. To get to the second balance, creating a Social Union would be the best solution because it would be legit, effective, and would help build a strong shared identity.

Notes:

[1] The Community method consists of three things: (i) the Commission’s monopoly on the right of legislative initiative, (ii) the Council and Parliament adopting the Commission’s proposals by co-decision, and (iii) the widespread use of qualified majority voting in the Council of Ministers.

[2] At the time, it was thought that all EU countries (apart from the « usual suspects ») would adopt the euro fairly quickly, which meant that there was no need to set up institutions/funds specific to the euro zone.

[3] With the development of mass politics after theFirstWorldWar, the pressures were such that the interwar gold standard system (fixed exchange rates and capital mobility) was untenable.

[4] The Schuman Declaration of 1950 laid down the principles of the European project: « Europe will not be made all at once, or according to a single plan. It will be built through concrete achievements which first create a de facto solidarity. […] [The ECSC] will lay the first concrete foundations of a European Federation, which is essential for the preservation of peace. »

References:

– Delle Donne, M. (2013), Banking union: will the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) replace Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) in the management of banking liquidity crises? , BSI Economics.

– Eichengreen, B. (2012), Is Europe on a Cross of Gold?, Project Syndicate

– Eurobarometer (2012 and 2013)

– Fabbrini, S. (2013), Intergovernmentalism and its limits: assessing the European Union’s answer to the crisis, Comparative Political Studies

– Frieda, G. (2013), Europe’s Clash of Generations, Project Syndicate

– Friedman, T. (2000), The Golden Straitjacket, In The Lexus and the Olive Tree (pp. 101-111), New York, NY, Anchor Books.

– Fukuyama, F. (2012), European Identities Part II, The American Interest

– Ganem, S. and A. van Marcke de Lummen (2013), European Employment Union, Le Cercle des Economistes.

– Ganem, S. (2014), Macroeconomic Stabilization in the Eurozone (Part I , Part II & Part III), BSI Economic.

– Lequillerier, V. (2012), And then came the Single Supervisory Mechanism… , BSI Economics.

– Letta, E. (2013), Europe’s Responsible Solidarity, Project Syndicate

– Micossi, S. (2013), How is the EZ crisis permanently changing the EU institutions?, CEPR

– Roubini, N. (2013), The Eurozone’s Calm Before the Storm, Project Syndicate

– Palacio, A. (2013), Europe’s Narrative Struggle, Project Syndicate

– Pisani-Ferry, J. (2012), Mutual insurance or federalism: the Eurozone between two models, Lyon Economics Days

– Pisani-Ferry, J., André Sapir, Guntram B. Wolff (2012), The Messy Rebuilding of Europe, Bruegel Policy Brief

– Rodrik, D. (2007), The inescapable trilemma of the world economy, Dani Rodrik’s weblog

– Šemeta, A. (2013), Europe at crossroads, College of Europe / Bruges