Macroeconomic stabilization in the eurozone: the eurozone’s inadequate institutional framework (III)

Summary:

– Monetary policy is procyclical and amplifies asymmetric shocks;

– Fiscal policy has several flaws that reduce its effectiveness;

– The Stability and Growth Pact, designed to reduce the scale of these flaws, has been largely ineffective and often insufficient;

The assumption that it was not necessary to promote greater economic integration to ensure the smooth functioning of the euro area has proved to be false. Member States have not had sufficient incentives to adapt to the constraints imposed by sharing a single currency with other heterogeneous entities. The market mechanisms designed to adjust or smooth out asymmetric shocks were implemented imperfectly, in a hurry, or proved ineffective. The lack of monitoring and correction of macroeconomic imbalances has been very damaging to the eurozone. They have been substantially reduced, but at a high cost.

Does the institutional framework nevertheless make it possible to compensate for this flaw in EMU? We will therefore focus on the last option available for stabilizing asymmetric shocks in the euro area: fiscal policy. But let us begin by clarifying the role that monetary policy has played in the overall institutional framework of the euro area.

Inflation differentials have disrupted the ECB’s monetary policy

In a monetary union, monetary policy is used to stabilize symmetric shocks. However, monetary policy played a key role in transmitting asymmetric shocks in the 2000s. The reason for this lies in the persistent inflation differentials between EMU member countries, which disrupted the countercyclical functions of the ECB’s policy (see Chart 1).

Source: Eurostat, Macrobond, BSI Economics (2013)

These persistent inflation differentials can have several causes: economic catch-up [1], labor market structure, economic policies, social preferences, and economic cycles. When inflation differentials between countries are low and stable, so too are the terms of trade, ultimately promoting balanced current accounts. The need for nominal exchange rate adjustments is therefore reduced. It is these same inflation differentials that have caused the dissolution of several monetary unions throughout history.

Inflation rates converged significantly during the 1990s. However, convergence was not yet complete when countries gave up their monetary policy autonomy in 1999. Furthermore, monetary integration did not reduce the dispersion of inflation rates in the 2000s, as some economists had anticipated.

As a result, the ECB’s monetary policy has often been procyclical and has amplified economic cycles within the euro area by promoting internal and external imbalances. This phenomenon has been transmitted through interest rates which, adjusted for inflation differentials, have been either too low for expanding economies or too high for stagnating economies.

Fiscal policy is generally less effective than monetary policy

Fiscal policy has two components: (i) an automatic component (automatic stabilizers) and (ii) a discretionary component (when the government decides on a stimulus or austerity plan). It is often this second component that is problematic. Fiscal policy must meet three conditions to be effective: it must be timely, temporary, and targeted. Fiscal policy is generally less effective than monetary policy for three reasons.

First, fiscal policy is subject to time lags: (i) a detection lag (real-time economic data is often of poor quality), (ii) a decision lag (budgetary processes that may be more or less effective), and (iii) an implementation lag (the effectiveness of fiscal policy depends on the adjustment of private agents’ behavior, which takes time). These lags contribute to reducing the countercyclicality of fiscal policy (Dullien and Schwarzer (2008) provide a good review of the literature on this subject). In general, the discretionary component reduces the effectiveness of automatic stabilizers and weakens the overall stabilizing function of fiscal policy.

Second, political economy teaches us that fiscal policy has a deficit bias that prevents the three conditions mentioned above from being met. According to Wyplosz, there are two main reasons for this phenomenon, which stems from the « tragedy of the commons , » namely (i) the tendency to shift the burden of fiscal adjustment onto future governments and generations, and (ii) the interaction of fiscal processes with interest groups (Wren-Lewis (2011) provides a comprehensive review of the issues). The fiscal balance is therefore often negative.

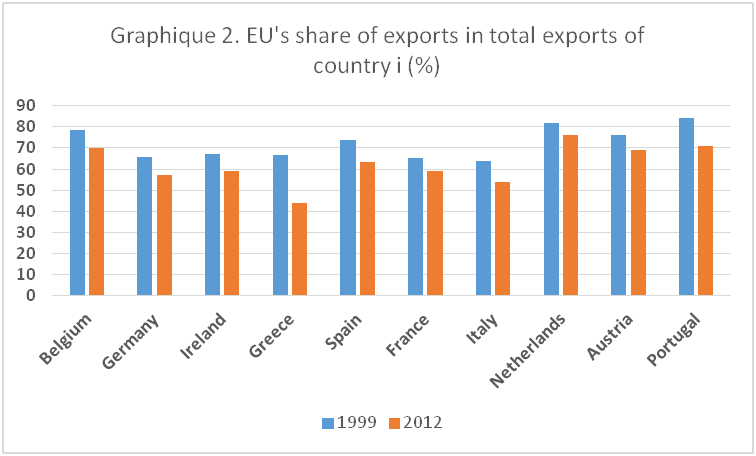

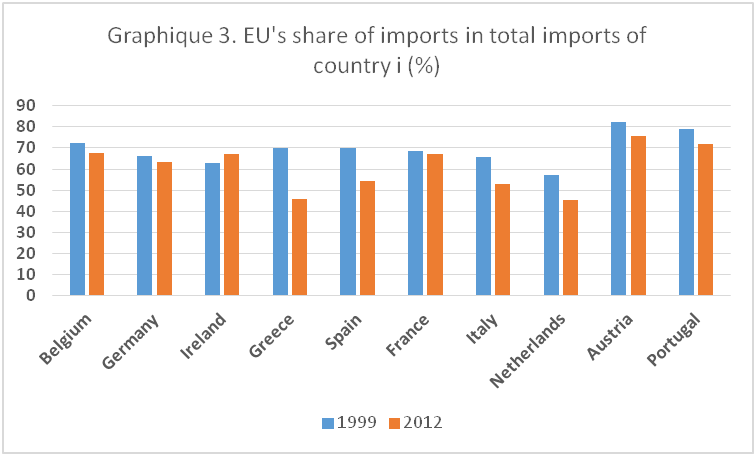

Third, fiscal policy is less effective in a monetary union because there are « leakages » on the fiscal multiplier, according to Goodhart and Smith. The main reason for this is the significant economic interdependence between euro area countries. In the EMU, most of each member state’s trade is with other member states (although the share of intra-zone trade is declining, see Figures 2 and 3). For example, if a country decides on a fiscal stimulus plan, a significant portion of the fiscal support is likely to translate into increased imports and benefit partner economies. This « leakage » of public money out of the national economy would minimize the effects on the domestic economy. This is a prisoner’s dilemma: instead of cooperating to maximize the effects of fiscal policy, each government will have an interest in going back on its word to minimize the scale of its stimulus and take advantage of the efforts of other partners. Ultimately, the scale of the stimulus will be suboptimal overall.

Source: Eurostat, Macrobond, BSI Economics (2013)

Why does the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) exist?

In a monetary union, fiscal rules are necessary to reduce the likelihood of free riding and moral hazard, which can reduce the effectiveness of monetary policy and increase the risk of contagion. According to Chari and Kehoe, if a central bank considers it optimal to set higher inflation when the level of debt is higher (this is known as « fiscal dominance »[4]), it provides incentives for a fiscal authority to free ride because part of the debt it has issued can be monetized in the future: each fiscal authority will therefore issue too much debt and jeopardize the targeting of optimal inflation. If a government borrows too much and pushes the central bank to increase inflation to liquidate the debt, the costs will be borne by all countries: fiscal rules must therefore be put in place to prevent and correct such behavior.

On the other hand, financial and monetary integration makes it possible to lower the cost of public debt for certain countries in the eurozone. Starting in 1999, spreads on sovereign bonds fell dramatically and converged toward very low German rates: these lower costs may have provided incentives for some countries to pursue less prudent fiscal policies. At the time, it was thought that the convergence of sovereign bond yields was permanent (indeed, until 2007, the financial markets made little distinction between Greek and German sovereign bonds). Furthermore, if a public financing problem were to arise, it was anticipated that the losses would be socialized (despite the no bailout clause, which, as we have seen, is not credible given the financial interdependencies between countries). The reckless behavior of one country could create uncontrollable chain reactions, which would be transmitted through the balance sheets of commercial banks. The aim is therefore to compel countries to adopt a responsible stance.

The effectiveness of the SGP is called into question by the facts

The SGP, which is the very essence of Maastricht orthodoxy, was designed to solve the problems we have just seen. The creators of the EMU framework believed that fiscal integration (in particular through the merger of all sovereign bonds into a single bond) was not necessary at the time: intergovernmental cooperation would be sufficient to prevent crises (the issue of crisis management did not even arise). It is reasonable to say that the results have been inconclusive: little nominal convergence, little cooperation between states (except perhaps in 2008-2009, when all euro area countries coordinated their fiscal efforts), but above all little real convergence (a major problem of macroeconomic imbalances).

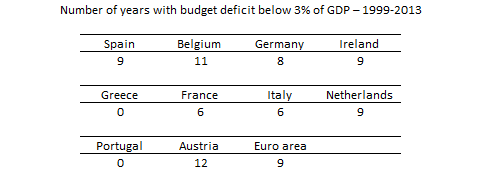

During the first 15 years of the euro’s existence, the SGP was only complied with in less than 50% of cases, on average for the 10 EMU countries considered in the table below. Even if the rule may have had a moderating influence on some countries (notably Ireland and Spain, which performed well in budgetary terms throughout the 2000s), the frequency with which it has been violated by major members is so high that its credibility is non-existent. In 2005, the SGP was « relaxed » after France and Germany managed to avoid sanctions under the excessive deficit procedure in 2003: states remain sovereign and do what they want when it comes to fiscal policy. The Maastricht framework is definitely not binding in practice.

Source: Eurostat, Macrobond, BSI Economics (2013)

The procyclicality of the SGP

According to Guntram Wolff of the Bruegel think tank, the deficit limit of 3% of GDP was generally considered sufficient to avoid disrupting the work of automatic stabilizers and to allow the discretionary component to be used if necessary. However, recent events show us that when it comes to extreme shocks (with a low probability), the framework set out by Maastricht is untenable.

The budget balance’s response to a shock is asymmetrical. In theory, the budget balance should be in equilibrium over the economic cycle. Buti and Sapir (1998) note that for the average EU country, when growth is below potential, the budget deficit gradually increases, while the budget balance only improves if growth is very strong.

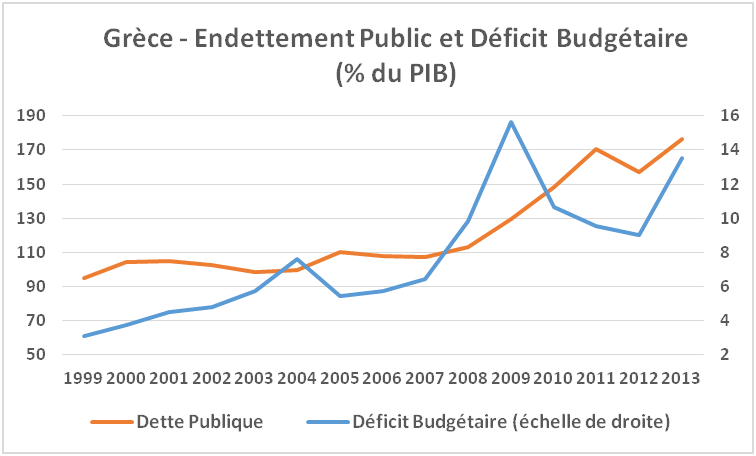

The SGP has been unable to address this problem because it was poorly designed, lacked credibility, and even proved to be procyclical. Some countries had to adopt austerity policies in the midst of a recession because they had not made sufficient budgetary efforts, notably by running budget surpluses during the good years [5]. Typical examples of this are Portugal and Greece. During the 2000s, they experienced very strong growth rates combined with very low real interest rates, but accumulated chronic budget deficits: public debt was therefore unable to decrease in anticipation of bad years (Figure 4).

Source: Eurostat, Macrobond, BSI Economics

The inadequacy of the SGP framework

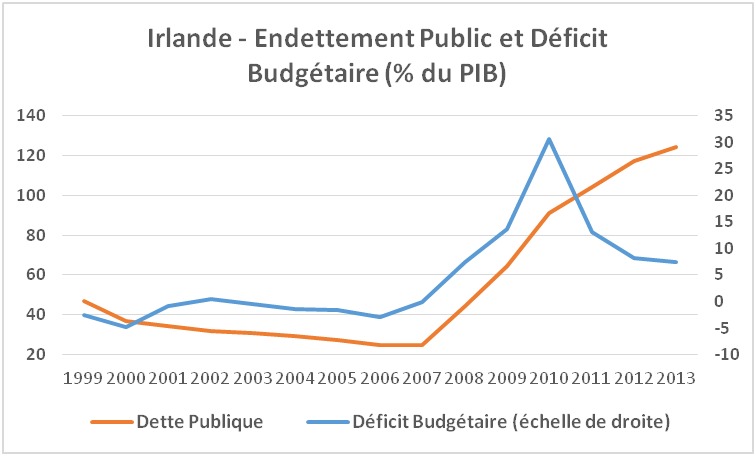

The case of countries such as Spain and Ireland is more complex to integrate into the SGP framework alone (Figure 5). With high growth rates, low real interest rates, and large budget surpluses, these countries were able to reduce their debt ratios very substantially. They therefore complied with the SGP criteria. Here again, the Maastricht EMU framework is at issue, as the SGP focused only on nominal convergence at the expense of real convergence. For example, private debt was underestimated. However, the implicit guarantee of private sector debt led to an extreme increase in public debt when private debt levels became unsustainable and financing came to a sudden halt. Ireland, for example, bailed out the private sector to the tune of 70% of GDP.

This is why the eurozone countries decided to add an economic pillar to the monetary pillar of EMU. Since the end of 2011, the Commission has been monitoring macroeconomic imbalances in order to prevent and correct them (Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure).

Source: Eurostat, Macrobond, BSI Economics

The original sin of the Eurozone

In 1999, two assumptions supported the logic of not delegating fiscal policy to a supranational authority, according to Wolff (director of Bruegel): (i) governments would be able to borrow on the financial markets according to their needs and (ii) the credit market would be able to share risks effectively. These two assumptions no longer hold true now that financial markets are fragmented in Europe. Countries must pursue pro-cyclical austerity policies in the midst of a recession, exacerbating the economic crisis and often also public debt [6].

This situation exists because financial markets can discriminate between the sovereign bonds of EMU countries by adjusting the risk premium, often according to the degree of external debt of the economies [7]. The increase in spreads on 10-year government bonds relative to the German Bund perfectly illustrates this phenomenon. This situation persists even though, compared to other countries, the eurozone as a whole has better fundamentals: for example, at the peak of the crisis, the United States and the United Kingdom had a deficit of 11.5% of GDP, while that of the eurozone stood at 6.5% (2009).

This phenomenon, which mostly affects developing countries, is called original sin: understanding the original sin of borrowing in a currency over which a debt-issuing country has no control. In 2011, De Grauwe showed (Figure 4), in a now famous example, that the United Kingdom borrows funds more cheaply than Spain, even though British public debt is higher than Spanish debt. The reason is simply that the United Kingdom has its own central bank and borrows mainly in pounds sterling, unlike Spain.

Figure 6. Original sin

Source: De Grauwe, BSI Economics

The schizophrenia of Eurozone governments

Put simply (we will address the issue of governance in the next article), the response of Eurozone countries has been to strengthen the SGP by prohibiting any structural budget deficit (the discretionary part of fiscal policy). Despite some improvements, notably through the automation of sanctions, ex ante supervision of national budgets, and better coordination of economic policies via the European Semester, this response is rather schizophrenic.

On the one hand, the latest reforms of European governance, decided by the states themselves and not imposed by Europe (in Europe, all decisions are taken more or less by consensus and the states control all stages of the decision-making process), prevent the use of any national fiscal policy in the future (if fiscal adjustment is successful in the coming decades), thus depriving them of the only tool at their disposal to deal with an asymmetric shock. On the other hand, these same states refuse supranational fiscal integration, which would make it possible to take over the fiscal stabilization that can no longer be achieved at the national level.

This apparent inconsistency is mainly due to the reluctance of European public opinion, which currently does not want this integration, which would come at a high cost in terms of national sovereignty.

Conclusion

We have now concluded our analysis of the economic and institutional system of the eurozone as designed by Maastricht. In summary, the Maastricht EMU 1.0 framework appears to be inadequate and inconsistent for ensuring a certain level of economic efficiency.

The assumption that fiscal integration is not necessary alongside monetary integration to meet the stabilization needs of each country has also proven to be false. It should be noted that such an institutional arrangement has never worked sustainably in history. Beyond the reduced effectiveness of fiscal policy in stabilizing economic cycles (monetary policy has also amplified these problems), the framework designed by Maastricht has proved inconsistent and inadequate. The response to the crisis is not necessarily any better.

At present, there is no stabilization mechanism capable of countering an asymmetric shock in the eurozone: the viability of EMU is therefore being called into question. The only possibility today is to make economies extremely flexible. This rather bitter assessment of the eurozone would argue for greater economic sovereignty. But on the contrary, it would be in the interest of European states and peoples to move towards greater economic and political integration. This is what we will attempt to explain in the last part of this series.

Notes

[1] This is the Balassa-Samuelson effect. Countries with relatively low per capita incomes tend to see their exchange rates revalue as they develop. Economic catch-up requires positive growth differentials, which are often accompanied by higher inflation.

[2] For several years now, the European countries that would form the Eurozone no longer had autonomy over their monetary policy, as it was aligned with that of the Bundesbank, which was the most effective. This is a concrete application of Mundell’s trilemma of incompatibility. Once a country allows capital movements and adopts a fixed exchange rate regime (European countries have always been « afraid of floating »), it no longer has autonomy over its monetary policy.

[3] This is a concept created by Hardin in 1968. Let us consider the budget balance as a common good. Each actor will act independently and rationally to maximize the net expenditure they receive from the state without internalizing the behavior of other actors. The aggregation of individual behaviors will run counter to the general interest by pushing the budget balance structurally downward.

[4] Monetary policy is contingent on budgetary stability: the Central Bank will increase its money supply to lower interest rates in order to have a negative interest rate-growth differential and facilitate debt reduction.

[5] The dynamics of public debt are a negative function of the « apparent interest rate-growth » differential on the existing stock of debt (snowball effect) and a positive function of the budget deficit (flow).

[6] Fiscal multipliers are very important because monetary policy is very accommodative and European countries are all pursuing fiscal austerity policies simultaneously (see Blanchard (2013) on this subject).

[7] During the 2000s, countries with current account deficits (mainly in southern Europe) had to borrow abroad to make up the difference, leading to a deterioration in their net external positions (the net external position is a country’s stock of net claims and liabilities vis-à-vis the rest of the world). This was easily achieved thanks to financial and global integration.

References

– Buti, M. and A. Sapir (1998). Economic Policy in EMU: a Study by the European Commission Services. Clarendon Press: Oxford.

– Chari, V. and P. Kehoe (1998). On the need for fiscal constraints in a monetary union. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Working Paper 589.

– Cimadomo, J. (2008). Fiscal policy in real time, ECB Working Paper No. 919.

– Delors, J. (2013). Economic Governance in the European Union: Past, Present and Future, Journal of Common Market Studies, Volume 51, Issue 2, pages 169–178.

– Dullien, S. and D. Schwarzer (2008). Bringing macroeconomics into the EU budget debate: Why and How?

– Ganem, S. (2014), Macroeconomic Stabilization in the Eurozone (I) . BSI Economics.

– Goodhart, C. and S. Smith (1993). Stabilization. European Economy – Reports and Studies No. 5, 417-455.

– De Grauwe, P. (2011). A Fragile Eurozone in Search of Better Governance. CESIFO WORKING PAPER NO. 3456.

– Lequillerier, V. (2012). The long and tumultuous road to financial stability in the eurozone . BSI Economics.

– Wolff, G. (2012). A budget for Europe’s monetary union. Bruegel Policy Brief Contribution. Issue 2012/22.

– Wren-Lewis, S. (2011). Comparing the Delegation of Monetary and Fiscal Policy. Discussion Paper 540, Department of Economics, Oxford University.

– Wyplosz, C. (2011). Fiscal Rules: Theoretical Issues and Historical Experiences. NBER conference on “Fiscal Policy after the Financial Crisis”, Milan, September 12-13.