Macroeconomic stabilization in the eurozone: market mechanisms are largely ineffective in the eurozone

Summary:

-In a monetary zone, either cycles are symmetrical, or adjustment or risk-sharing mechanisms are needed to stabilize an asymmetric shock.

-Labor mobility is low in the Eurozone. Internal unemployment imbalances are not being resolved

-Prices are relatively inflexible and adjusting them is very costly in terms of unemployment.

-The financial integration of the 2000s, which is one of the reasons for the internal imbalances in the eurozone, has now given way to financial fragmentation. It is difficult for financial markets to smooth consumption.

-Overall, market mechanisms are ineffective in the eurozone.

In the first part of this series , we presented the theory of optimal currency areas (OCAs) to understand the underlying economic mechanisms in the eurozone and, above all, the political and economic constraints that monetary integration places on eurozone countries. The conclusion is as follows: (i) the countries on the periphery of the eurozone were not ready to adopt the single currency in the 1990s because the costs outweighed the benefits at the time, (ii) this is not necessarily a disaster, as the situation is not static and may change. In this second part, we will attempt to determine whether the direction taken by the eurozone since 1999 has been the right one.

The challenge for a monetary zone is to determine whether asymmetric shocks are present and, if so, whether there are stabilization mechanisms in place to deal with them. Stabilization mechanisms operate through two channels: (i) market mechanisms or (ii) institutional instruments (economic policies, macroeconomic framework). They can take two forms: (i) a risk-sharing system to smooth consumption and income after a positive or negative shock (fiscal or financial integration), or (ii) promoting the adjustment of relative prices after an economic disruption (flexibility of goods and labor markets, labor mobility).

In Europe, it would appear that there are asymmetric shocks whose intensity has not decreased since 1999, contrary to the predictions of some economists (see the first article). The period since 1999 can be divided into three parts: (i) a positive (negative) shock for the periphery (core) from the early 2000s until the subprime crisis, (ii) a symmetric shock following the subprime crisis in 2008-2009, and (iii) a negative (positive) shock for the periphery (core) since then. However, the literature is unclear on the convergence/divergence of cycles in the eurozone due to the heterogeneity of the methods and data used.

Have the countries of the eurozone nevertheless succeeded in developing stabilization mechanisms? Here, we will focus on market mechanisms: labor mobility, price flexibility, and financial integration. In each case, we will review the associated theoretical framework and then analyze the empirical situation.

Labor mobility as an adjustment mechanism

High factor mobility (particularly labor mobility) in a monetary union can reduce the need for nominal exchange rate adjustment in response to an asymmetric shock. Let us take the example given by Mundell in his seminal paper. If there is a negative demand shock for goods from region A in favor of those from region B, and if prices and wages are partly rigid (particularly on the downside), this will cause inflationary pressures in region B and unemployment in region A. If these regions have a common currency, monetary policy is ineffective in dealing with this asymmetric shock. On the other hand, if there is high internal labor mobility between A and B, then the unemployed in region A will move to region B: there will therefore no longer be unemployment in region A, nor inflationary pressures in region B. The loss of the exchange rate and monetary policy will not be costly: adjustment by quantities allows relative prices to be adjusted in a relatively painless manner to reach a new stable equilibrium.

Unfortunately, it is extremely weak given the persistent imbalances in unemployment

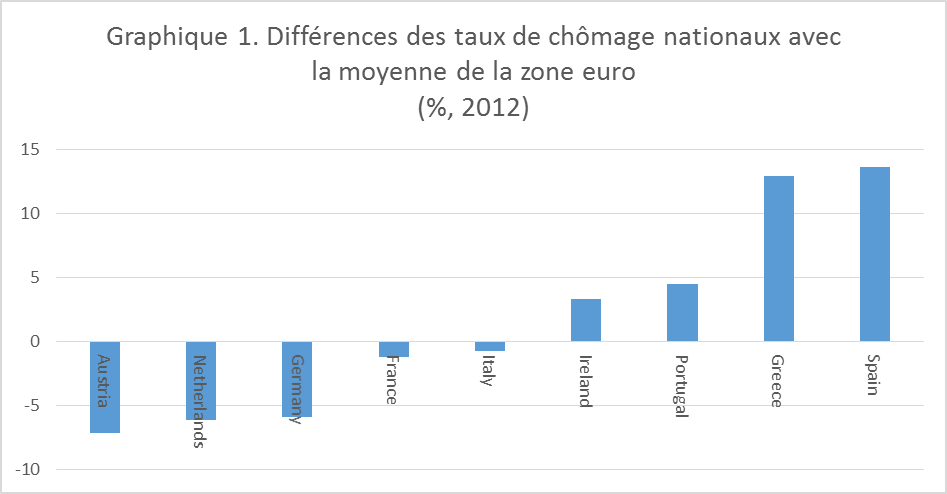

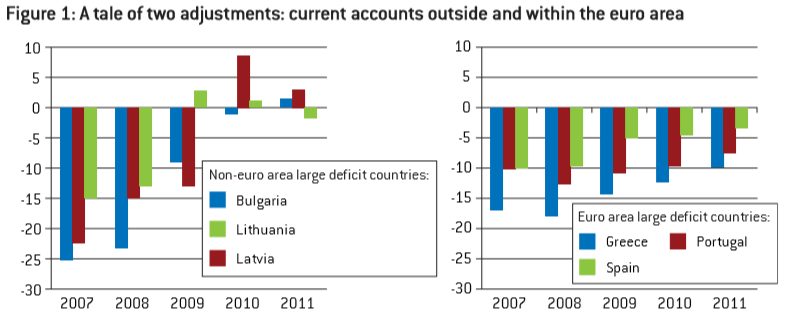

The crisis in Europe is above all a balance of payments and private debt crisis, with current account imbalances within the eurozone growing steadily from 1999 to 2007. Public debt is merely a consequence of these imbalances (except perhaps in Greece). With current positions becoming unsustainable since the end of financing by capital from the core of the eurozone in 2007 (known as « sudden stops, » see the article by Merler and Pisani-Ferry (2012)), peripheral countries have had to reduce their demand in order to reduce their deficits. This has led to a significant increase in unemployment in these countries and has therefore created major imbalances within the eurozone (Figure 1).

Source: Eurostat, Macrobond, BSI Economics (2013)

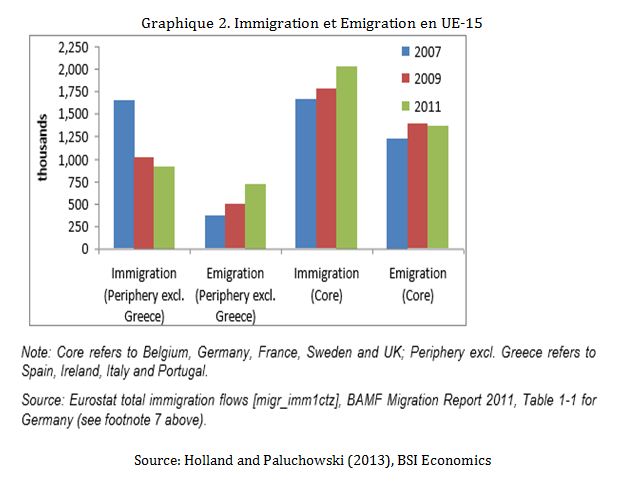

Intra-European mobility (see Figure 2) slowed significantly in the aftermath of the financial crisis: immigration to southern countries fell sharply but was not immediately offset by increased immigration to the north. Since 2011, the rate of intra-EU-15 mobility appears to be gradually recovering. Net migration to northern countries has increased, while the migration balance in the south has fallen sharply. In 2011, Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain recorded net outflows of migrants, in contrast to their pre-crisis trend. Labor inflows to the North have been largely directed towards Germany, where labor market conditions are significantly better than in the rest of the EU-15. Emigration from the periphery remains low in volume, however, given the scale of internal labor market imbalances. Theoretical free movement of workers within the EU does not appear to act as an effective buffer against asymmetric shocks. Worker mobility is therefore not an option for the euro area at present: growing flows are still too weak to have a substantial effect.

Adjustment could be achieved by making markets more flexible…

When labor mobility is low, as is the case in Europe, adjustment following an asymmetric shock can be achieved directly through prices rather than through quantities. For Mundell, a negative asymmetric shock in region A is less likely to be associated with lasting unemployment in region A and inflation in region B if the prices of goods and labor are flexible. If this is not the case, the loss of the nominal exchange rate instrument, as well as the loss of monetary policy autonomy, represents a substantial cost.

Price flexibility (for goods and labor) would also be endogenous to the creation of a monetary union. The deregulation of goods markets, increased competition following the deepening of the Single Market, and monetary integration make it possible to reduce monopoly rents in relatively closed markets. This has consequences for the labor market, as workers’ incentives to protect these rents would be reduced. As a result, prices would be more flexible depending on the state of productivity and the economy at a given moment. Furthermore, the loss of the nominal exchange rate would push for wage restraint, as any imbalance in the balance of payments could not be instantly adjusted by the exchange rate.

However, the loss of monetary and exchange rate policy would also reduce the incentives to undertake large-scale labor and product market reforms, as political leaders would be unable to compensate the short-term losers of these structural reforms. As we pointed out in the previous article, economic dynamics in a monetary union are never unidirectional a priori.

… but this is not yet possible because goods prices are still rigid

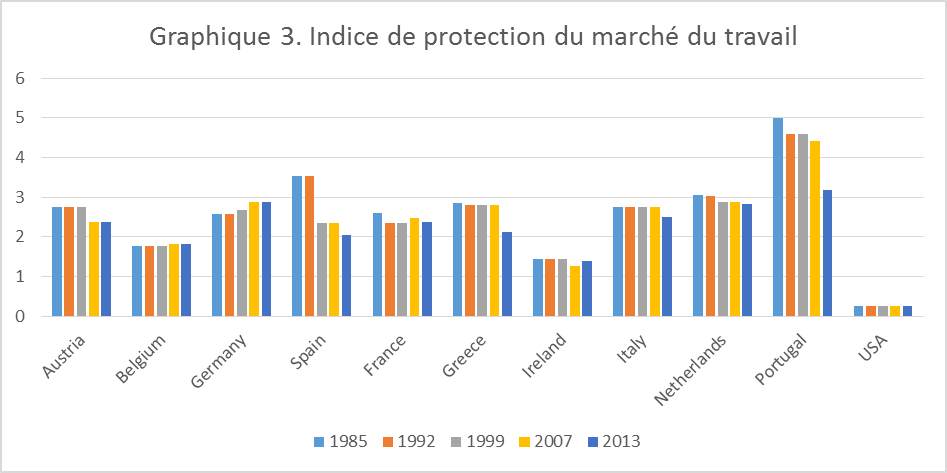

After a convergence effort in the 1990s, structural reforms slowed in most countries after the launch of the common currency. This is what we learn from OECD data, respectively the EPL (Employment Protection Legislation) index (Figure 3) and the PMR (Product Market Regulation) index.

Source: OECD, BSI Economics (2013)

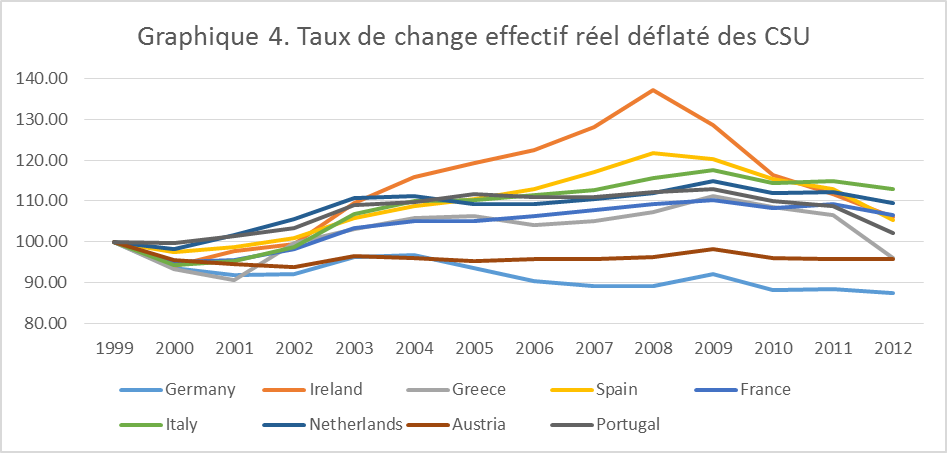

On the other hand, an analysis of real effective exchange rates (REER [1]) since 1999 shows a significant divergence between the South and the North (Figure 4). Southern countries have seen their REERs, deflated by prices and unit labor costs, increase significantly, while the REERs of Northern countries have remained fairly stable or have declined slightly. While Northern countries adopted wage restraint policies in the 2000s, Southern countries experienced the opposite dynamic, particularly because their growth was higher. These higher growth rates resulted in higher inflation rates and excessively low real interest rates, which fueled a spiral of competitiveness loss. Before the crisis, it was accepted that these dynamics were simply a virtuous phenomenon of catching up in terms of living standards.

Source: Eurostat (2013), BSI Economics

This situation of effective exchange rate imbalances now has significant consequences, as southern countries are forced to pursue deflationary policies with three effects: (i) debt reduction is made more difficult, (ii) unemployment, particularly long-term unemployment, increases, and (iii) as a result of (i) and (ii), social security structures, which are at the heart of European societies’ compromises (market economy with solidarity mechanisms for the losers), are put at risk.

Real internal adjustment is very costly and time-consuming because of downward price rigidity: a flexible exchange rate would allow all prices to be adjusted instantly and the balance of payments to be re-balanced. In addition, the length and scale of the adjustment may be accompanied by possible hysteresis effects [2] via losses in human capital.

With regard to price flexibility, it can also be observed that it is the countries under programs (with the exception of Ireland, which already had a flexible market, as can be seen from its exchange rate, which adjusted rapidly) that have seen their labor market rigidities considerably reduced in order to facilitate rebalancing (Figure 3). Figure 4 shows us (i) that countries not under attack from the markets are not implementing reforms to lower their real effective exchange rates and (ii) that the entire burden is being borne by the southern countries. Neither Germany nor Austria is supporting internal rebalancing by increasing their labor costs (or prices).

Although we do not have recent data on the flexibility of the goods market, we can infer this from the CPI-deflated REERs, which show that price rigidity at the European level makes it difficult to increase price competitiveness (the reason being that the service sectors are still not very competitive). On the other hand, the South is lowering its wages, but the small price differences with the North do not allow it to gain price competitiveness: this prevents internal adjustment and fuels deflationary pressures in the South, as purchasing power is reduced due to lower real wages.

Market mechanisms based on prices will not be fully effective until goods prices are flexible. The implementation of deflationary structural reforms in the context of a major recession also exacerbates the social crisis.

Financial integration could prove to be a useful risk-sharing mechanism

A system of risk sharing between countries can reduce the need for nominal exchange rate adjustments in the event of an asymmetric shock, since the shock would be diluted across the entire area, reducing its impact on the affected country (Kenen, 1969). Financial integration appears to be a risk-sharing system for Ingram (1962). It would smooth consumption and income through (i) easier access to credit in the event of a negative income shock and (ii) portfolio diversification.

Financial integration is perfect when all participants (i) are subject to a single set of rules for deciding to buy and sell financial instruments or services, (ii) have equal access to financial instruments or services, and (iii) are treated equally when operating in the market. Financial integration has three advantages: (i) it creates a risk-sharing system to smooth consumption and income over time, (ii) it allows for better factor allocation, and (iii) it promotes growth.

The use of financial markets was also the idea of Mundell (1973), who considered that the presence of asymmetric shocks in a monetary area was not fatal. In the absence of capital controls, credible fixed exchange rates (through the adoption of a common currency) would encourage international portfolio diversification in order to share the risks of asymmetric shocks and reduce their negative effects within a monetary union through the presence of these stabilization mechanisms. For example, several authors show that financial integration (capital and credit markets) in the United States would cushion an asymmetric shock in a state by around 60%. For developed countries, the figure is 40%. This would increase the symmetry of shocks to income and consumption, even if there are asymmetric shocks to production.

However, financial integration has contradictory effects. Theoretically, there is also a negative relationship between financial integration and the symmetry of economic cycles, since the presence of a risk-sharing system would promote industrial specialization, as predicted by Krugman (see article I). According to standard microeconomic insurance analysis, individuals are willing to take on more production risks if financial market integration improves. They can insure themselves more effectively and borrow more easily in a larger, more liquid market. As a result, production risks are less of a concern since incomes can be stabilized.

The misleading dynamics of the 2000s

According to a 2008 ECB report, financial integration was complete in terms of money and credit markets, even if capital markets were not yet fully integrated at the time. The euro would have been an important catalyst for financial integration if we exclude the crisis years: it promoted the ownership of intra-eurozone bonds and equities, while reducing national bias. However, Guntram Wolff, the current director of Bruegel, believes that the capital market’s shock absorption channel, which is so important in the United States, would not be as effective in the euro area because asset holdings are still heavily biased towards domestic assets.

Let us now look back at what happened in the 2000s in terms of current account imbalances, as financial integration played an important role. In national accounting, a current account can be expressed as the difference between an economy’s savings and investment. If savings exceed investment, the country has a current account surplus (and vice versa).

Before the Eurozone crisis, economists believed that current account imbalances between the North and South were virtuous and reflected a normal phenomenon of real convergence in living standards: this was the thesis of Blanchard and Giavazzi. Countries with relatively lower GDP per capita than others have lower capital intensities, i.e., higher rates of return: one euro of capital in a country on the periphery of the Eurozone would therefore yield more than one euro invested in the core. Capital will then flow from north to south, which will increase investment (assumed to be productive) in the south and reduce the current account balance. Furthermore, if southern countries anticipate stronger potential growth in the future, since financial integration would allow for a positive productivity shock through more productive investment, savings, mainly private (since public savings are controlled by the Stability and Growth Pact), will decrease. This is because economic agents prefer to smooth their consumption over time: if they anticipate higher incomes in the future, they will start consuming more today and reduce their savings. This has the effect of deteriorating the current account balance. However, this temporary deficit would be offset by a surplus in the future thanks to increased productivity.

With the benefit of hindsight, it is reasonable to say that the positive shock of the 2000s for peripheral countries was not real (no increase in productivity) because capital from the North financed low-productivity investments and fueled financial bubbles. The increase in financial asset prices created a wealth effect for households, which wanted to consume more. They were able to do so through widespread access to credit that banks were able to offer thanks to financial integration. As a result, current account balances deteriorated in peripheral countries, while savings were abundant in core countries (thanks to policies that discouraged consumption).

At the same time, growth (and inflation) differentials with the North, favored by financial integration that supported demand, led to a loss of competitiveness in Southern countries. This resulted in worsening current account imbalances and Southern economies turning to non-tradable goods sectors.

When the bubbles burst, capital stopped flowing in Europe and southern countries suffered a balance of payments crisis. However, the euro played a protective role (via public capital, Target 2 balances, etc.), as a balance of payments crisis normally requires almost immediate economic adjustment. The countries of the eurozone did not experience this violent adjustment, unlike the EU countries outside the eurozone (see Merler and Pisani Ferry, 2012).

Source: Merler and Pisani-Ferry (2012), BSI Economics

The problem of financial fragmentation exacerbates the crisis

Since the beginning of the crisis, the eurozone has experienced rapid financial fragmentation, raising many fundamental questions, particularly about the transmission of monetary policy to the real economy. This is evident from the ECB’s 2013 report on financial integration. Benoit Coeuré, member of the ECB’s Executive Board, brings together several empirical elements to support the presence of financial fragmentation in the euro area: (i) the money market has become increasingly fragmented as interest rates diverge between countries (EURIBOR and Eonia), (ii) cross-border bank lending is declining, with risk premiums varying from country to country, (iii) spreads on government bonds are widening (with consequences for all other interest rates in national economies), and (iv) financial portfolios are being renationalized.

Jorg Asmussen, member of the ECB’s Executive Board, sees three causes for financial fragmentation: (i) high levels of public debt in certain eurozone countries, which, combined with banks’ balance sheets heavily weighted with bonds from their respective governments that are losing value, create vicious circles (the banking union was created, among other things, to break these so-called « doom loops » between sovereign and bank securities), (ii) weak growth, which discourages banks from taking risks, particularly when it comes to lending to SMEs, and (iii) weak bank balance sheets.

This financial fragmentation is hindering any sustainable recovery from the crisis. There have been some signs of a decline in financial fragmentation since July 2012 and Draghi’s speech. However, the situation remains unsatisfactory and the economic situation in some countries leads us to believe that risk sharing through financial integration does not exist or no longer exists. The eurozone has lost 10 years of integration with the current crisis.

Conclusion

The eurozone is facing recurring asymmetric shocks. However, this observation is not necessarily a deal-breaker for EMU: if stabilization and adjustment mechanisms were in place, the effects of asymmetric shocks would be substantially reduced.

Unfortunately, we have just shown that market stabilization is of little or no use in the eurozone. States cannot therefore really turn to this solution to resolve their short-term stabilization problems. It should be noted, however, that reforms that are very costly socially today may have positive effects in the medium and long term. The problem for Eurozone countries is knowing how to balance these reforms so as not to create permanent negative consequences. The decision to slow down austerity and reforms is a step in the right direction to avoid the social and political unrest that has been looming for some time.

The search for a stabilization system for the eurozone is not yet over: will the institutional tools available to countries enable them to resolve the problem of stabilization in the eurozone?

Notes

[1] The TCER is the weighted average (the weighting being specific to each country) of the exchange rates of the national currency against the currencies of competing countries in a given zone. The weighting depends on the intensity of trade relations. The TCER deflated by consumer prices is an (imperfect) index of price competitiveness. For the TCER deflated by unit labor costs, it is cost competitiveness.

[2] Hysteresis, in economics, refers to the persistence of an economic phenomenon even after its main cause has disappeared.

References

– Asdrubali, P., B. E. Sørensen, and O. Yosha (1996). Channels of interstate risk sharing: United States 1963–90. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111, 1081–110.

– Asmussen, J. (2013). Reintegrating financial markets. General Assembly of the European Savings Banks Group, Berlin, June 14, 2013.

– Coeuré, B. (2013). The way back to financial integration. Conference organized by the Banco de España and the Reinventing Bretton Woods Committee, Madrid, March 12, 2013.

– Duval, R. and J. Elmeskov (2005). The Effects of EMU on Structural Reforms in Labor and Product Markets. OECD Economics Department Working Paper No. 438.

– ECB (2008 and 2013), Financial Integration in Europe, European Central Bank, Frankfurt am Main.

– Ganem, S. (2014). Macroeconomic Stabilization in the Euro Area (I) . BSI Economics

– Holland, D. and P. Paluchowski (2013). Geographical labor mobility in the context of the crisis. National Institute of Economic and Social Research.

– Kalemli-Ozcan, S., B. E. Sørensen, and O. Yosha (2003). Risk sharing and industrial specialization: regional and international evidence. American Economic Review, 93, 903–16.

– Kalemli-Ozcan, S., E. Papaioannou, and J. L. Peydro (2008). Banking Integration, Synchronization, and Volatility. Mimeo.

– Merler, S. and J. Pisani-Ferry (2012). Sudden stops in the euro area. Policy Contribution 2012/06, Bruegel.

– Wolff, G. (2012). A budget for Europe’s monetary union. Bruegel Policy Brief Contribution. Issue 2012/22.